South Africa's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best Interests of the Child Are of Paramount

WHERE TO FIND THE FAMILY ADVOCATE IN YOUR AREA: ISSUED 2018 ENGLISH National Office Sibasa Mthatha Adv. C.J Maree Northern Cape George Adv. Petunia Seabi-Mathope Adv. R.D. Ramanenzhe Adv. M.S. Van Pletzen (Senior Family Advocate) Kimberley – Provincial Office Adv. J. Gerber Chief Family Advocate (Family Advocate) (Senior Family Advocate) Tel: 012 323 0760, Fax: 012 323 9566 Adv. P.M Molokwane (Senior Family Advocate) Ms C. Molai (Secretary to the Chief Tel: 015 960 1410 Tel: 047 532 3998, Pretoria [email protected] (Acting Principal Family Advocate) Tel: 044 802 4200, Family Advocate) [email protected] Fax: 047 532 5337 Postal Address: Private Bag X 88, (Senior Family Advocate) Fax: 044 802 4202 OFFICE OF THE FAMILY ADVOCATE Tel: 012 357 8022 Postal Address: Private Bag X 5005 [email protected] Pretoria, 0001. Tel: 053 833 1019/63, [email protected] Fax: 012 357 8043 Thohoyandou 0950. Physical Address: Postal Address: Private Bag X 5255 Physical Address: 4th Floor, Centre Fax: 053 833 1062/69 Postal Address: Private Bag X 6586, [email protected] Thohoyandou Magistrate Court Mthatha 5099. Physical Address: 6th Walk Building, C/o Thabo Sehume [email protected] George, 6530. Physical Address: Postal Address: Private Bag X 6071, THE BEST INTERESTS Postal Address: Private Bag X 81 Floor, Manpower Building, C/o & Pretorius Streets , Pretoria, 0001 Cnr Cradock & Cathedral Street, Pretoria 0001. Physical Address: Mpumalanga Elliot and Madeira Street, Kimberley, 8300. Physical Address: Bateleur Park Building, George, 329 Pretorius Street, Momentum Nelspruit – Provincial Office Mthatha, 5100 Soshanguve 5th Floor, New Public Building OF THE CHILD ARE Building, West Tower, Pretoria Adv. -

Basic Itinerary for 10 Day Golf Tour: Cape Town – Port Elizabeth

www.freewalker.co.za Facebook: Freewalker Adventure Travel 10 day South African Golf Adventure |Cape Town –Eastern Cape via Garden Route This packaged tour starts in Cape Town (voted one of the best Cities to visit in the World),playing at the highly rated Steenberg Golf & Wine Estate and The Royal Cape, which is Africa’s oldest Club. The Tour continues along the World famous Garden Route to Fancourt Resort & Lifestyle Estate for a leisurely experience. The Pezula Golf Course on the Knysna cliffs is the final destination before heading off into our Big 5 Safari region for an abundance of wildlife experiences in the Eastern Cape, the Adventure Province. Basic itinerary for 10 day golf tour: Cape Town – Port Elizabeth Day 1: Arrival in South Africa Met at Cape Town International Airport by Freewalker Guide Check in at Cape Town accommodation (4 nights) Group drinks, dinner & brief at V&A Waterfront Day 2: Steenberg Golf & Wine Estate Breakfast at accommodation or Golf Club 18 holes on Steenberg Golf Course Lunch & drinks at Club house Wine tasting on Estate/Groot Constantia Estate Dinner on the coast of Kalk Bay Day 3: Sight-seeing around the Cape Peninsula Breakfast at accommodation Table Mountain cable car and viewing from the top Cape Point Nature Reserve visit (Southern-most tip of Africa) Lunch at the Two Oceans Restaurant (overlooking the famous False Bay) Peninsula drive via Chapman’s Peak and Hout Bay Sunset drinks and dinner at the cosmopolitan Camps Bay Day 4: Oldest Golf course in Africa day Breakfast at accommodation or Golf -

South Africa Yearbook 2012/13

SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2012/13 Land and its p Land and its people Situated at the southern tip of Africa, South Africa boasts an amazing variety of natural beauty and an abundance of wildlife, birds, Land and its p plant species and mineral wealth. In addi- tion, its population comprises a unique diversity of people and cultures. The southern tip of Africa is also where archaeologists discovered 2,5-million-year- old fossils of man’s earliest ancestors, as well as 100 000-year-old remains of modern man. The land Stretching latitudinally from 22°S to 35°S and longitudinally from 17°E to 33°E, South Africa’s surface area covers 1 219 602 km2. According to Census 2011, the shift of the national boundary over the Indian Ocean in the north-east corner of KwaZulu-Natal to cater for the Isimangaliso Wetland Park led to the increase in South Africa’s land area. Physical features range from bushveld, grasslands, forests, deserts and majestic mountain peaks, to wide unspoilt beaches and coastal wetlands. The country shares common bound- aries with Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Swaziland, while the Mountain Kingdom of Lesotho is landlocked by South African territory in the south-east. The 3 000-km shoreline stretching from the Mozambican border in the east to the Namibian border in the west is surrounded by the Atlantic and Indian oceans, which meet at Cape Point in the continent’s south- western corner. Prince Edward and Marion islands, annexed by South Africa in 1947, lie some 1 920 km south-east of Cape Town. -

Table 2 BUILT-UP URBAN AREAS by LAND AREA (URBAN FOOTPRINT)

Table 2 BUILT-UP URBAN AREAS BY LAND AREA (URBAN FOOTPRINT) Urban Areas 500,000 & Over Population Land Area Population Density Source: Population Square Square Per Square Per Square Pop.Area Rank Geography Urban Area Estimate Miles Kilometers Mile Kilometer (See Note) 1 United States New York, NY-NJ-CT 20,685,000 4,495 11,642 4,500 1,800 N:N 2 Japan Tokyo-Yokohama 37,750,000 3,300 8,547 11,400 4,400 C:B 3 United States Chicago, IL-IN-WI 9,185,000 2,647 6,856 3,400 1,300 N:N 4 United States Atlanta, GA 5,120,000 2,645 6,851 1,700 700 A:A 5 United States Los Angeles, CA 15,135,000 2,432 6,299 6,000 2,400 N:N 6 United States Boston, MA-NH-RI 4,490,000 2,056 5,325 2,100 800 N:N 7 Russia Moscow 16,570,000 2,050 5,310 8,100 3,100 C:B 8 United States Dallas-Fort Worth, TX 6,280,000 1,998 5,175 2,800 1,200 N:N 9 United States Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD 5,595,000 1,981 5,131 2,700 1,100 A:A 10 United States Houston, TX 6,005,000 1,864 4,828 2,800 1,200 N:N 11 China Beijing, BJ-HEB 20,390,000 1,520 3,937 13,400 5,200 L:B 12 China Shanghai, SHG-JS-ZJ 22,685,000 1,500 3,885 15,100 5,800 L:B 12 Japan Nagoya 10,035,000 1,500 3,885 6,700 2,600 C:B 14 China Guangzhou-Foshan, GD 18,760,000 1,475 3,820 12,700 4,900 L:B 15 United States Detroit, MI 3,660,000 1,337 3,463 2,800 1,100 A:A 16 United States Washington, DC-VA-MD 4,950,000 1,322 3,424 3,500 1,300 A:A 17 Indonesia Jakarta 31,320,000 1,245 3,225 25,200 9,700 C:B 17 United States Phoenix, AZ 4,295,000 1,245 3,225 3,100 1,300 N:N 19 Japan Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto 16,985,000 1,240 3,212 13,700 5,300 C:B 20 United States Miami, FL 5,820,000 1,239 3,209 4,400 1,700 A:A 21 United States Seattle, WA 3,475,000 1,154 2,989 2,800 1,100 N:A 22 France Paris 10,870,000 1,098 2,845 9,600 3,700 A:A 23 United States San Francisco-San Jose, CA 5,955,000 1,080 2,797 5,400 2,100 N:N 24 Brazil Sao Paulo 20,605,000 1,045 2,707 19,700 7,600 C:B 25 Argentina Buenos Aires 14,280,000 1,035 2,681 13,800 5,300 C:B 26 Germany Essen-Dusseldorf 6,675,000 1,025 2,655 6,500 2,500 C:B 27 United States Minneapolis-St. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 47085 Slum Upgrading Experiences ofSixCities The CitiesAlliance n 1 © The Cities Alliance, 2008 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. http://www.citiesalliance.org/index.html All rights reserved First printing, October 2008 The material in this publication is copyrighted. Requests for permission to reproduce whole or portions of it should be directed to the Cities Alliance Secretariat at the above address. The Cities Alliance encourages the active dissemination of its knowledge. Permission to disseminate will normally be granted promptly and, when reproduction is for noncommercial purposes, without asking for a fee. Cover Photo: São Paulo Photographer: Daniel Ducci Design: Patricia Hord.Graphik Design Printing: Jarboe Commercial Printing Company Slum Upgrading Experiences of Six Cities ii n Slum Upgrading Up Close: Experiences of Six Cities The Cities Alliance n iii Learning with São Paulo On behalf of the Cities Alliance and city of São Paulo, we are pleased to present Slum Upgrading Up Close: Experiences of Six Cities. The publication captures some of the key knowledge and shared learning from an international policy dialogue on the “Challenges of Slum Upgrading: Sharing São Paulo’s Experience” held in São Paulo from March 10 to 14, 2008. Co-sponsored by the Cities Alliance and the city of São Paulo, the five-day event facilitated a rich exchange of ideas among high-ranking city officials from six major cities of the south—Cairo, Ekurhuleni, Lagos, Manila, Mumbai, and São Paulo—on the issues and challenges of slum upgrading in their respective cities. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Redefining Global Cities the Seven Types of Global Metro Economies

REDEFINING GLOBAL CITIES THE SEVEN TYPES OF GLOBAL METRO ECONOMIES REDEFINING GLOBAL CITIES THE SEVEN TYPES OF GLOBAL METRO ECONOMIES GLOBAL CITIES INITIATIVE A JOINT PROJECT OF BROOKINGS AND JPMORGAN CHASE JESUS LEAL TRUJILLO AND JOSEPH PARILLA THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM | 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ith more than half the world’s population now living in urban areas, cities are the critical drivers of global economic growth and prosperity. The world’s 123 largest metro areas contain a little Wmore than one-eighth of global population, but generate nearly one-third of global economic output. As societies and economies around the world have urbanized, they have upended the classic notion of a global city. No longer is the global economy driven by a select few major financial centers like New York, London, and Tokyo. Today, members of a vast and complex network of cities participate in international flows of goods, services, people, capital, and ideas, and thus make distinctive contributions to global growth and opportunity. And as the global economy continues to suffer from what the IMF terms “too slow growth for too long,” efforts to understand and enhance cities’ contributions to growth and prosperity become even more important. In view of these trends and challenges, this report redefines global cities. It introduces a new typology that builds from a first-of-its-kind database of dozens of indicators, standardized across the world’s 123 largest metro economies, to examine global city economic characteristics, industrial structure, and key competitive- ness factors: tradable clusters, innovation, talent, and infrastructure connectivity. The typology reveals that, indeed, there is no one way to be a global city. -

Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL ^REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS for the YEARS 1

Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL ^REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS FOR THE YEARS 1981-1982 Marine Geoscience Group Department of Geology University of Cape Town December 1982 NGU-Tfc—Kh JOINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY/UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN MARINE GEOSCIENCE UNIT TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 13 PROGRESS REPORTS FOR THE YEARS 1981-1982 Marine Geoscience Group Department of Geology University of Cape Town December 1982 The Joint Geological Survey/University of Cape Town Marine Geoscience Unit is jointly funded by the two parent organizations to promote marine geoscientific activity in South Africa. The Geological Survey Director, Mr L.N.J. Engelbrecht, and the University Research Committee are thanked for their continued generous financial and technical support for this work. The Unit was established in 1975 by the amalgamation of the Marine Geology Programme (funded by SANCOR until 1972) and the Marine Geophysical Unit. Financial ?nd technical assistance from the South African National Committee for Oceanographic Research, and the National Research Institute for Oceanology (Stellenbosch) are also gratefully acknowledged. It is the policy of the Geological Survey and the University of Cape Town that the data obtained may be presented in the form of theses for higher degrees and that completed projects shall be published without delay in appropriate media. The data and conclusions contained in this report are made available for the information of the international scientific community with tl~e request that they be not published in any manner without written permission. CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION by R.V.Dingle i PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE BATHYMETRY OF PART OF 1 THE TRANSKEI BASIN by S.H. -

Port of Port Elizabeth Information

Port of Port Elizabeth Information LOCATION Latitude 34º 01’S | Longitude 25º 42’E PILOTAGE Pilotage is compulsory. Rendezvous point is 2.2 nautical miles NE of the port entrance on the leading lights. Pilot transfer is by pilot boat, unless otherwise advised. When pilot is embarking by pilot boat, ladders must comply with SOLAS regulations. Port Elizabeth has one fast pilot boats equipped with radar and VHF telephone. WATER DENSITY Seawater density in the harbour is 1.024g/cm³. PILOT BOARDING POSITION Off the Fairway buoy. PORT LIMITS The entrance channel has a max draft of 11.80 Metres, however with the Port Captain's permission and on a rising tide vessel with a draft of 12.05 Metres have been able to sail from the port; this however is subject to the individual draft restrictions at the cargo berths. Diamond Shipping Services, South Africa ~ 1 ~ Updated: 10/2017 Port of Port Elizabeth Information APPROACHES The anchorage positions differ, the vessel must contact port control on channel 12 once approaching and port control will advise the vessel accordingly. TIDE Tide fall at mean high water springs is 1.72 m and 0.37 and mean low water neaps. WEATHER "The Windy City" has a subtropical climate with light rain throughout the year. Under the Köppen climate classification, Port Elizabeth has an oceanic climate. The area lies between the winter rainfall, Mediterranean climate zones of the Western Cape and the summer rainfall regions of eastern South Africa. Winters are cool but mild and summers are warm but considerably less humid and hot than more northerly parts of South Africa's east coast. -

Exploring Health and Healthcare Systems in South Africa

IPE 3050: PUBLIC HEALTH AND HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS IN SOUTH AFRICA Professor Robert Bensley, PhD [email protected] 269-716-2301 Description: The proposed travel study course will focus on current health promotion and healthcare issues in South Africa, especially within the Nelson Mandela Metropol in the Eastern Cape. South Africa is currently under extreme healthcare duress, leading the world in HIV infection and experiencing a host of other public health related factors, including poverty, violence, alcoholism, and HIV-related infections. The country has experienced great strides following a long history of segregation associated with Apartheid. However, public health systems, including healthcare, continue to be a disparity for cultures within South Africa. Much of this is related practices that evolved due to Apartheid, however, rich cultural traditions also play key factors in how native populations approach preventative health and healthcare. One of the major goals of the US Healthy People 2020 objectives for the nation focuses on eliminating health disparities among US populations. The proposed program is designed to not only provide students with a global understanding of the complexities that exist within international health practices, but also serve as a platform for providing a deeper understanding of the consequences of health disparities as it relates to our own cultures. This course will include a series of formal and informal meetings with different public health and healthcare individuals and groups, visits to health and healthcare institutions, cultural activities and immersion, hands-on service learning involvement, and group discussions. In particular, students will be exposed to a number of healthcare practitioners, personnel from public health and non-profit centers and clinics, university-based wellness peer helpers, and traditional healers. -

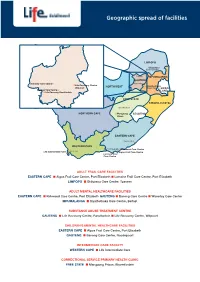

Geographic Spread of Facilities

Geographic spread of facilities LIMPOPO Shiluvana Care Centre Pretoria MPUMALANGA GAUTENG Waverley Care Centre Johannesburg Life Recovery Centre NORTH WEST Siyathuthuka Witpoort Care Centre SWAZI- Baneng Care Centre LAND Life Recovery Randfontein FREE STATE KWAZULU-NATAL Bloemfontein NORTHERN CAPE Mangaung LESOTHO Prison EASTERN CAPE East London WESTERN CAPE Port Elizabeth Kirkwood Care Centre Cape Town Life Intermediate Care Algoa Frail Care Centre Lorraine Frail Care Centre ADULT FRAIL CARE FACILITIES EASTERN CAPE ■ Algoa Frail Care Centre, Port Elizabeth ■ Lorraine Frail Care Centre, Port Elizabeth LIMPOPO ■ Shiluvana Care Centre, Tzaneen ADULT MENTAL HEALTHCARE FACILITIES EASTERN CAPE ■ Kirkwood Care Centre, Port Elizabeth GAUTENG ■ Baneng Care Centre ■ Waverley Care Centre MPUMALANGA ■ Siyathuthuka Care Centre, Belfast SUBSTANCE ABUSE TREATMENT CENTRE GAUTENG ■ Life Recovery Centre, Randfontein ■ Life Recovery Centre, Witpoort CHILDREN'S MENTAL HEALTHCARE FACILITIES EASTERN CAPE ■ Algoa Frail Care Centre, Port Elizabeth GAUTENG ■ Baneng Care Centre, Roodepoort INTERMEDIATE CARE FACILITY WESTERN CAPE ■ Life Intermediate Care CORRECTIONAL SERVICE PRIMARY HEALTH CLINIC FREE STATE ■ Mangaung Prison, Bloemfontein Facilities Head office Hospitals – inland region Managing director – Life Esidimeni Baneng Care Centre Puseletso Jaure Acting hospital manager: David Moshabe Oxford Manor, 21 Chaplin Road, Illovo 2196 91 Leader Road, Robertville, Roodepoort 1709 Private Bag X13, Northlands 2116 PO Box 2181, Florida 1710 Tel: 011 219 9170 Tel: -

George Municipality

MUNICIPAL PROFILE George Municipality George local municipality is located on the south eastern coast of South Africa and ± 440 km southeast of Cape Town. George enjoys the strategic advantage of being situated on the major transport routes between Cape Town in the south and Port Elizabeth in the east. This creates investment opportunities, particularly with regard to manufacturing, logistics and warehousing. The municipal area is 5190.43 km² in scope and includes the following: the City of George, the villages of Wilderness and Herolds Bay, various coastal resorts such as Kleinkrantz and Victoria Bay, rural areas around Rondevlei (east of Wilderness), Geelhoutboom, Herold, Hansmoeskraal and Waboomskraal, as well as Uniondale and Haarlem. The IDP envisions George “to be the best medium sized city in the country using all available resources sustainably to the benefit of the community in a growing and a thriving city.” CONTEXTUAL MAP OF MUNICIPALITY UNIONDALE! HAARLEM! GEORGE! WILDERNESS! HEROLDS BAY! SETTLEMENT CATEGORISATIONS SETTLEMENT CATEGORY SETTLEMENT CATEGORY Spandiel Street (Rosemoor) C Syferforntein C Malagasrivier B1 Erf 329 B1 Erf 1424 (behind primary school) C Kleinkrantz West C Sonop Avenue (7 de Laan) C Kleinkrantz Middle C Golden Valley C Kleinkrantz East C Spandiel Street C Touwsranten North C Erf 4200 (Palma) B1 Touwsranten South C Fingland Street C Noordstraat C Nel Street (Erf 21882) B1 Erf 181 B1 Bellair Street C Mingo Kamp C Between Sunset & De Beer Street (Erven 21990 Agter Street B1 C & 22021) July Markeni Street B1 Conville 1 B1 Mgoqi Street C Conville 2 B1 Florence Ntondini Street C Uniondale A Circular & Satumus Street B2 Haarlem I C Protea Park (back area) C Haarlem II C Protea Park (front area) A & C Haarlem III C Haarlem IV C MUNICIPAL PROFILE: GEORGE MUNICIPALITY INTRODUCTION The information in this municipal profile provides an overview of (back area) and Protea Park (front area).