Surveying for Reptiles Tips, Techniques and Skills to Help You Survey for Reptiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very European Tale – Britain Still Has Only Three Snake Species, but Its Grass Snake Is Now Assigned to Another Species (Natrix Helvetica)

SHORT COMMUNICATION The Herpetological Bulletin 141, 2017: 44-45 A very European tale – Britain still has only three snake species, but its grass snake is now assigned to another species (Natrix helvetica) UWE FRITZ1* & CAROLIN KINDLER1 1Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden, Museum of Zoology, A. B. Meyer Building, 01109 Dresden, Germany *Corresponding author Email: [email protected] ollowing several investigations of the phylogeography and systematics of grass snakes (Fritz et al., 2012; FKindler et al., 2013, 2014; Pokrant et al., 2016), we published a further detailed study on this topic in August (Kindler et al., 2017). Our new investigation revealed that only very limited gene flow occurs between western barred grass snakes and eastern common grass snakes. Consequently, we concluded that the barred grass snake (Fig. 1), previously a subspecies, should be elevated to a full species. August being the ‘silly season’ for news stories led the local media, including the highly respected BBC, to claim that Britain has now an additional snake species, i.e. four instead of three species – the northern viper (Vipera Figure 1. Young N. helvetica showing the distinctive lateral bars berus), the smooth snake (Coronella austriaca) as well as from which the species common name the ‘barred grass snake’ is derived (photo: © Jason Steel) two species of grass snake, the common grass snake (Natrix natrix) and the newly recognised barred grass snake (Natrix helvetica). findings. However, some southern populations identified This upheaval resulted from a complete misunderstanding by Thorpe with barred grass snakes, for instance from of a press release by the Senckenberg Institution. The press northern Italy, turned out to be distinct from N. -

Pseudopus Apodus (PALLAS, 1775) from Jordan, with Notes on Its Ecology (Sqamata: Sauria: Anguidae)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 18_3_4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Rifai Lina B., Abu Baker Mohammad, Disi Ahmad M., Mahasneh Ahmad, Amr Zuhair S., Al Shafei Darweesh Artikel/Article: Pseudopus apodus (PALLAS, 1775) form Jordan, with notes on ist ecology 133-140 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA 18 (3/4): 133 - 140 133 Wien, 30. Dezember 2005 Pseudopus apodus (PALLAS, 1775) from Jordan, with notes on its ecology (Sqamata: Sauria: Anguidae) Pseudopus apodus (PALLAS, 1775) von Jordanien, mit Bemerkungen zu seiner Ökologie (Sqamata: Sauria: Anguidae) LINA RIFAI & MOHAMMAD ABU BAKER & DARWEESH AL SHAFEI & AHMAD DISI & AHMAD MAHASNEH & ZUHAIR AMR KURZFASSUNG Weitere Exemplare der Panzerschleiche Pseudopus apodus (PALLAS, 1775) werden aus Jordanien beschrie- ben. Morphologische und ökologische Merkmale sowie die gegenwärtig bekannte Verbreitung werden dargestellt. Pseudopus apodus ist in seinem jordanischen Vorkommen auf die Berge im mediterran beeinflußtenen Norden beschränkt. Die mittlere Anzahl der Rücken- und Bauchschuppenquerreihen sowie das Verhältnis von Kopflänge zu Kopfbreite jordanischer Exemplare werden mit Angaben für P. apodus apodus und P. apodus thracicus (OBST, 1978) verglichen. Im Magen und Darm von sieben Exemplaren aus Jordanien fanden sich Überreste von Arthro- poden und Mollusken, wobei Orthopteren den zahlenmäßig größten Anteil an Nahrungsobjekten ausmachten. ABSTRACT Further specimens of the Glass Lizard Pseudopus apodus (PALLAS, 1775) are described from Jordan. Mor- phological and ecological characters as well as the currently known distribution in Jordan are presented. In Jordan, Pseudopus apodus is confined to the northern Mediterranean mountains. -

Amphibians and Reptiles in South Wales the Difference Between Amphibians and Reptiles

Amphibians & Reptiles i n S o u t h W a l e s ! ! ! ! ENVT0836 Amphibians and Reptiles in South Wales The difference between Amphibians and Reptiles Grass Snake © SWWARG Amphibians and reptiles are two ancient ! groups of animals that have been on the Smooth Newt © ARC planet for a very long time. The study of amphibians and reptiles is known as Amphibians, such as frogs, toads and ! Herpetology. To simplify matters, both newts, possess a porous skin that, when groups of animals will be referred to moist, exchanges oxygen meaning they throughout this booklet collectively as breathe through their skin. All amphibian Herpetofauna. Examples of both groups species in South Wales have to return to of animals live throughout South Wales water for breeding purposes. Adult and display a fascinating range of amphibians lay spawn in fresh water behaviour and survival tactics. bodies which then hatch and pass through a larval or tadpole stage prior to Common Lizard- female © SWWARG metamorphosing into miniature versions of the adults. • Generally possess smooth, moist skin • Generally slow moving Herpetofauna populations in South Wales • Generally in or around water are under ever increasing pressure due to a variety of reasons such as habitat loss, Common Toad © SWWARG colony isolation and human encroachment. There are many ways in which we can assist this group of misunderstood animals, which this booklet will attempt to highlight so that the reader can make their own valuable contribution towards helping to conserve both the animals and their habitat. ! page one Reptiles such as snakes and lizards, like amphibians, are cold blooded or ectotherms. -

Population Structure and Translocation of the Slow-Worm, Anguis Fragilis L

Population structure and translocation of the Slow-worm, Anguis fragilis L. D. S. HUBBLE1 and D. T. HURST2 1 7 Ainsley Gardens, Eastleigh, Hampshire SO50 4NX, UK E-mail: [email protected] [Corresponding author] 2 3 Bye Road, Swanwick, Hamphsire SO31 7GX, UK ABSTRACT — Proposed redevelopment work in Petersfield, Hampshire required capture and translocation of Slow-worms to fulfil the legal obligations of 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act (as amended). Numbers of adult males, adult females and juveniles were recorded. Only 3 of 577 Slow-worms captured were found moving or basking on the surface. On days with high capture rates, females and juveniles were more active. The disturbance pattern due to sampling, as well as human activity not related to translocation, affected capture rates. The settling-in period for refugia was not as important as believed. When translocating Slow-worms, it is important to ensure significant capture effort is made throughout the season rather than attempting to choose ‘suitable’ conditions. It is also important to ensure that the density of refugia placement is as high as possible. LTHOUGH frequently occurring close to Although attempts have been made to Ahuman habitation, the Slow-worm is poorly standardise reptile survey methods (Reading, understood due to its secretive behaviour, the 1996, Reading, 1997), there is no single accepted difficulty of studying individuals over long standard methodology for surveying reptile periods and the subsequent lack of detailed study populations (RSPB et al., 1994). UK Government (Beebee & Griffiths, 2000). The species is body English Nature advise that the method used widespread in the South and South East of for translocation should be based on guidelines England but there are indications of a decline produced by the Herpetofauna Groups of Britain during the second half of the 20th century (Baker et and Ireland (HGBI, 1998). -

From Montenegro

Correspondence ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com Melanism in Natrix natrix and Natrix tessellata (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Montenegro SLA ĐANA GVOZDENOVI Ć1* and MARIO SCHWEIGER 2 1 Montenegrin Ecologist Society, Bulevar Sv. Petra Cetinjskog 73, Podgorica, Montenegro. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Vipersgarden, Katzelsberg 4, 5162 Obertrum, Ӧsterreich. E-mail: [email protected] Received 13 November 2014 │ Accepted 10 December 2014 │ Published online 11 December 2014. The coloration in animals plays an important role in predator avoidance (Sweet 1985), inter- and intraspecific communication and sexual selection (Roulin & Bize 2006). Different color morphs occur in many reptiles, and the most frequent one is melanism, especially in snakes (Lorioux et al . 2008). There exist few advantages of this phenomen as: faster heating rates, higher mean body temperatures, protection from overheating (Luiselli 1992; Forsman 1995; Bittner et al . 2002; Tanaka 2005; Clusella-Trullas et al . 2008), but also disadvantages, such as higher predation risk (Clusella-Trullas et al., 2008). Melanism in European snakes has been reported for: Zamenis longissimus , Hierophis viridiflavus , Coronella austriaca , Platyceps najadum , Natrix maura , Natrix natrix , Natrix tessellata , Vipera berus , Vipera aspis (Terhivuo 1990; Cattaneo 2003; Zuffi 2008; Pernetta & Reading 2009; Strugariu & Zamfirescu 2009; Zadravec & Lauš 2011; Mollov 2012; Ajti ć et al . 2013). Figures 1-2. Left (Fig. 1): Black dice snake Natrix tessellata from river Bojana, Ulcinj. Right (Fig. 2): Black grass snake Natrix natrix persa from Tanki rt, Skadar Lake Ecol. Mont., 1 (4), 2014, 231-233 231 MELANISM IN NATRIX NATRIX AND N.TESSELLATA FROM MONTENEGRO In this paper we present melanism in two species: Natrix natrix (Linnaeus, 1758) and Natrix tessellata (Laurenti, 1768) from Montenegro. -

Crested Newts Triturus Carnifex

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2002 Band/Volume: 15_1_2 Autor(en)/Author(s): Filippi Ernesto, Luiselli Luca M. Artikel/Article: Crested Newts Triturus carnifex (LAURENTI, 1768), form the bulk of the diet in high-altitude Grass Snakes Natrix natrix (LINNAEUS, 1758), of the central Apennines 83-85 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at HERPETOZOA15(l/2):83-85 83 Wien, 30. Juni 2002 Crested Newts Triturus carnifex (LAURENTI, 1768), form the bulk of the diet in high-altitude Grass Snakes Natrix natrix (LINNAEUS, 1758), of the central Apennines (Caudata: Salamandridae; Squamata: Colubridae) Kamm-Molche - Triturus carnifex (LAURENTI, 1768) - als Hauptbestandteil der Nahrung von Hochgebirgs-Ringelnattern - Natrix natrix (LINNAEUS, 1758) - im Zentralapennin (Caudata: Salamandridae; Squamata: Colubridae) ERNESTO FILIPPI & LUCA LUISELLI KURZFASSUNG Wir berichten über die Zusammensetzung der Nahrung von Ringelnattern Natrix natrix (LINNAEUS, 1758), einer isolierten Population im Bereich eines Hochgebirgs-Gletschersees im Naturreservat 'Montagne della Duchessa' im Velino Massiv (Apenninen). Die Körperlänge der Weibchen lag (statistisch nicht signifikant) gering- fügig über der der Männchen. Bei einer Wiederfangrate von 50%, zeigte ein allgemeines MANOVA-Modell mit der Kopf-Rumpf-Länge (KRL) als Kovariate, daß kein Geschlecht bevorzugt wiedergefangen wurde. Nahrungsobjekte waren ausschließlich Amphibien. Abgesehen von einer Larve der Erdkröte Bufo bufo (LIN- NAEUS, 1758) in einer männlichen Natter von 37,0 cm KRL, wurden ausschließlich adulte Kamm-Molche Triturus carnifex (LAURENTI, 1768), als Nahrungstiere festgestellt. Sehr wahrscheinlich liegt dies daran, daß diese Molche im Untersuchungsgewässer die bei weitem häufigste Amphibienart darstellen. -

The IWT National Survey of the Common Lizard (Lacerta Vivipara) in Ireland 2007

The IWT National Survey of the Common Lizard (Lacerta vivipara) in Ireland 2007 This project was sponsored by the National Parks and Wildlife Service Table of Contents 1.0 Common Lizards – a Description 3 2.0 Introduction to the 2007 Survey 4 2.1 How “common” is the common lizard in Ireland? 4 2.2 History of common lizard surveys in Ireland 4 2.3 National Common Lizard Survey 2007 5 3.0 Methodology 6 4.0 Results 7 4.1 Lizard sightings by county 7 4.2 Time of year of lizard sightings 8 4.3 Habitat type of the common lizard 11 4.4 Weather conditions at time of lizard sighting 12 4.5 Time of day of lizard sighting 13 4.6 Lizard behaviour at time of sighting 14 4.7 How did respondents hear about the National Lizard Survey 2007? 14 5.0 Discussion 15 6.0 Acknowledgements 16 7.0 References 17 8.0 Appendices 18 1 List of Tables Table 1 Lizard Sightings by County 9 Table 2 Time of Year of Lizard Sightings 10 Table 3 Habitat types of the Common Lizard 12 Table 4 Weather conditions at Time of Lizard Sighting 13 Table 5 Time of Day of Lizard Sighting 13 Some of the many photographs submitted to IWT during 2007 2 1.0 Common Lizard, Lacerta vivipara Jacquin – A Description The Common Lizard, Lacerta vivipara is Ireland’s only native reptile species. The slow-worm, Anguis fragilis, is found in the Burren in small numbers. However it is believed to have been deliberately introduced in the 1970’s (McGuire and Marnell, 2000). -

Reptile Habitat Management Handbook

Reptile Habitat Management Handbook Paul Edgar, Jim Foster and John Baker Acknowledgements The production of this handbook was assisted by a review panel: Tony Gent, John Buckley, Chris Gleed-Owen, Nick Moulton, Gary Powell, Mike Preston, Jon Webster and Bill Whitaker (Amphibian and Reptile Conservation); Dave Bird (British Herpetological Society); Lee Brady (Calumma Ecological Services and Kent Reptile and Amphibian Group); John Newton and Martin Noble. The authors are grateful for input from, and discussion with, many other site managers and reptile ecologists, especially Dave Bax, Chris Dresh, Mike Ewart, Barry Kemp, Nigel Hand, Gemma Harding, Steve Hiner, Peter Hughes, Richie Johnson, Kevin Morgan, Mark Robinson, Mark Warne and Paul Wilkinson. The text benefited greatly from a workshop run by Paul Edgar and Jim Foster at the Herpetofauna orkers’W Meeting in 2007 – many thanks to all who contributed. The copyright of the photographs generously donated for this publication remains with the photographers. Note that no criticism is intended of any site managers or organisations whose sites feature in photographs characterised here as poor habitat for reptiles. The images have been chosen simply to illustrate key points of principle. Their inclusion here is not a comment on the management or condition of the sites depicted. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation thanks Natural England for financial support in producing this handbook. Amphibian and Reptile Conservation is also grateful to the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation for support through the Widespread Species Project. Feedback contact details We welcome any suggestions for improving this handbook. Please email [email protected] with ‘RHMH feedback’ as the subject. -

Amphibians and Reptiles

Amphibians and reptiles Introduction Churchyards can be great places for amphibians and reptiles, and especially Did you know? important for slow worms and common lizard which have declined elsewhere. If the churchyard is close to ponds you may even find common Unlike frogs, toads don’t frogs, common toads and newts. Open sunny spots as well as sheltered hop, but walk, and if areas such as hedge bases and longer grass areas provide food and shelter. disturbed will often sit very still. This helps to distinguish The importance of churchyards for amphibians and the two species. reptiles The smooth newt is Churchyards add to a network of green sites, such as meadows and occasionally mistaken for a gardens, enabling the movement of species such as these through the lizard and their skin can look landscape. The mosaic of habitats in churchyards including grassland velvety when they are on of varying lengths, hedgerows, piles of dead leaves, compost heaps, land. tombstones and scrubby areas provide good homes for amphibians and reptiles. Look out for common frog, common toad, smooth newt, common lizard, grass snake and slow worm. The common lizard incubates its eggs internally without laying shelled eggs. A slow worm is in fact a lizard with no legs and has a flat forked tongue. Common frog by David Tottmann Common toad by Elizabeth Dack For further information please visit the NWT website or contact: NWT Churchyard Team Tel: 01603 625540 Norfolk Wildlife Trust Email: [email protected] Bewick House Website: www.norfolkwildlifetrust.org.uk Thorpe Road, Norwich NR1 1RY Grass snake by Julian Thomas Saving Norfolk’s Wildlife for the Future Where to find amphibians and reptiles Common lizard Common frog by Elizabeth Dack by Neville Yardy Slow worm by David Gittens The common lizard is a colourful Frogs have slender bodies, smooth The slow worm has a smooth and character, being a shade of brown skin and jump and hop, whereas shiny snake-like body. -

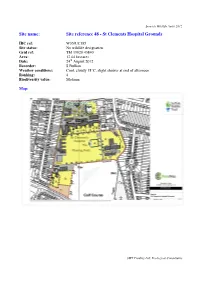

Site Name: Site Reference 48 - St Clements Hospital Grounds

Ipswich Wildlife Audit 2012 Site name: Site reference 48 - St Clements Hospital Grounds IBC ref: W35/UC185 Site status: No wildlife designation Grid ref: TM 19020 43840 Area: 12.64 hectares Date: 24 th August 2012 Recorder: S Bullion Weather conditions: Cool, cloudy 18°C, slight shower at end of afternoon Ranking: 4 Biodiversity value: Medium Map: SWT Trading Ltd: Ecological Consultants Ipswich Wildlife Audit 2012 Photos: Car park looking north-east towards woodland belt on road frontage Hospital buildings viewed from south SWT Trading Ltd: Ecological Consultants Ipswich Wildlife Audit 2012 Rough grassland in south-west corner Outbuildings in south-west Habitat type(s): Short mown grass, un-mown rough grassland, tall grass and scrub, tree belt Subsidiary habitats: Mature/veteran trees SWT Trading Ltd: Ecological Consultants Ipswich Wildlife Audit 2012 Site description: Within this large site are the older buildings of the St Clements Hospital as well as more modern buildings throughout the site. A mature tree belt screens the buildings from the Foxhall Road. Amenity grassland surrounds most of the buildings, but the eastern areas have been left unmown at the time of the survey. To the rear of the main hospital buildings are former gardens and much of the centre of the site is occupied by a playing field within which is a bowls square screened by a beech hedge. To the south-west are a sports/recreational centre and football pitch and also older buildings which may have been former stabling/coach houses. The small plot of land adjoining the railway line is rough grassland and scrub, with mature pine trees. -

The Herpetofauna of Wiltshire

The Herpetofauna of Wiltshire Gareth Harris, Gemma Harding, Michael Hordley & Sue Sawyer March 2018 Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre and Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group Acknowledgments All maps were produced by WSBRC and contain Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database right 2018. Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre staff and volunteers are thanked for all their support throughout this project, as well as the recorders of Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group and the numerous recorders and professional ecologists who contributed their data. Purgle Linham, previously WSBRC centre manager, in particular, is thanked for her help in producing the maps in this publication, even after commencing a new job with Natural England! Adrian Bicker, of Living Record (livingrecord.net) is thanked for supporting wider recording efforts in Wiltshire. The Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Publications Society are thanked for financially supporting this project. About us Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre Wiltshire & Swindon Biological Records Centre (WSBRC), based at Wiltshire Wildlife Trust, is the county’s local environmental records centre and has been operating since 1975. WSBRC gathers, manages and interprets detailed information on wildlife, sites, habitats and geology and makes this available to a wide range of users. This information comes from a considerable variety of sources including published reports, commissioned surveys and data provided by voluntary and other organisations. Much of the species data are collected by volunteer recorders, often through our network of County Recorders and key local and national recording groups. Wiltshire Amphibian & Reptile Group (WARG) Wiltshire Amphibian and Reptile Group (WARG) was established in 2008. It consists of a small group of volunteers who are interested in the conservation of British reptiles and amphibians. -

Amphibians & Reptiles in the Garden

Amphibians & Reptiles in the Garden Slow-worm by Mike Toms lthough amphibians and reptiles belong to two different taxonomic classes, they are often lumped together. Together they share some ecological similarities and may even look superficially similar. Some are familiar A garden inhabitants, others less so. Being able to identify the different species can help Garden BirdWatchers to accurately record those species using their gardens and may also reassure those who might be worried by the appearance of a snake. Only a small number of native amphibians and reptiles, plus a handful of non-native species, breed in the UK. So, with a few identification tips and a little understanding of their ecology and behaviour, they are fairly easy to identify. This guide sets out to help you improve your identification skills, not only for general Garden BirdWatch recording, but also in the hope that you will help us with a one-off survey of these fascinating creatures. Several of our amphibians thrive in the garden and five of the native Amphibians species, Common Frog, Common Toad and the three newts, can reasonably be expected to be found in the garden for at least part of the year. There are also a few introduced species which have been recorded from gardens, together with our remaining native species, which although rare need to be considered for completeness. Common Frog: (right) Rana temporaria Common Toad: (below) Grows to 6–7 cm. Bufo bufo Predominant colour Has ‘warty’ skin which looks is brown, but often dry when the animal is on variable, including land.