Synapse Type-Specific Proteomic Dissection Identifies Igsf8 As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

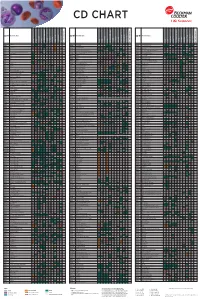

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Supp Material.Pdf

Simon et al. Supplementary information: Table of contents p.1 Supplementary material and methods p.2-4 • PoIy(I)-poly(C) Treatment • Flow Cytometry and Immunohistochemistry • Western Blotting • Quantitative RT-PCR • Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization • RNA-Seq • Exome capture • Sequencing Supplementary Figures and Tables Suppl. items Description pages Figure 1 Inactivation of Ezh2 affects normal thymocyte development 5 Figure 2 Ezh2 mouse leukemias express cell surface T cell receptor 6 Figure 3 Expression of EZH2 and Hox genes in T-ALL 7 Figure 4 Additional mutation et deletion of chromatin modifiers in T-ALL 8 Figure 5 PRC2 expression and activity in human lymphoproliferative disease 9 Figure 6 PRC2 regulatory network (String analysis) 10 Table 1 Primers and probes for detection of PRC2 genes 11 Table 2 Patient and T-ALL characteristics 12 Table 3 Statistics of RNA and DNA sequencing 13 Table 4 Mutations found in human T-ALLs (see Fig. 3D and Suppl. Fig. 4) 14 Table 5 SNP populations in analyzed human T-ALL samples 15 Table 6 List of altered genes in T-ALL for DAVID analysis 20 Table 7 List of David functional clusters 31 Table 8 List of acquired SNP tested in normal non leukemic DNA 32 1 Simon et al. Supplementary Material and Methods PoIy(I)-poly(C) Treatment. pIpC (GE Healthcare Lifesciences) was dissolved in endotoxin-free D-PBS (Gibco) at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. Mice received four consecutive injections of 150 μg pIpC every other day. The day of the last pIpC injection was designated as day 0 of experiment. -

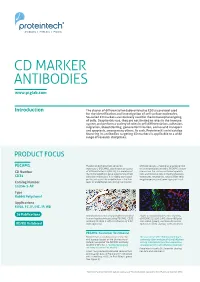

CD Markers Are Routinely Used for the Immunophenotyping of Cells

ptglab.com 1 CD MARKER ANTIBODIES www.ptglab.com Introduction The cluster of differentiation (abbreviated as CD) is a protocol used for the identification and investigation of cell surface molecules. So-called CD markers are routinely used for the immunophenotyping of cells. Despite this use, they are not limited to roles in the immune system and perform a variety of roles in cell differentiation, adhesion, migration, blood clotting, gamete fertilization, amino acid transport and apoptosis, among many others. As such, Proteintech’s mini catalog featuring its antibodies targeting CD markers is applicable to a wide range of research disciplines. PRODUCT FOCUS PECAM1 Platelet endothelial cell adhesion of blood vessels – making up a large portion molecule-1 (PECAM1), also known as cluster of its intracellular junctions. PECAM-1 is also CD Number of differentiation 31 (CD31), is a member of present on the surface of hematopoietic the immunoglobulin gene superfamily of cell cells and immune cells including platelets, CD31 adhesion molecules. It is highly expressed monocytes, neutrophils, natural killer cells, on the surface of the endothelium – the thin megakaryocytes and some types of T-cell. Catalog Number layer of endothelial cells lining the interior 11256-1-AP Type Rabbit Polyclonal Applications ELISA, FC, IF, IHC, IP, WB 16 Publications Immunohistochemical of paraffin-embedded Figure 1: Immunofluorescence staining human hepatocirrhosis using PECAM1, CD31 of PECAM1 (11256-1-AP), Alexa 488 goat antibody (11265-1-AP) at a dilution of 1:50 anti-rabbit (green), and smooth muscle KD/KO Validated (40x objective). alpha-actin (red), courtesy of Nicola Smart. PECAM1: Customer Testimonial Nicola Smart, a cardiovascular researcher “As you can see [the immunostaining] is and a group leader at the University of extremely clean and specific [and] displays Oxford, has said of the PECAM1 antibody strong intercellular junction expression, (11265-1-AP) that it “worked beautifully as expected for a cell adhesion molecule.” on every occasion I’ve tried it.” Proteintech thanks Dr. -

Single-Cell Analysis Uncovers Fibroblast Heterogeneity

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17740-1 OPEN Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination ✉ Lars Muhl 1,2 , Guillem Genové 1,2, Stefanos Leptidis 1,2, Jianping Liu 1,2, Liqun He3,4, Giuseppe Mocci1,2, Ying Sun4, Sonja Gustafsson1,2, Byambajav Buyandelger1,2, Indira V. Chivukula1,2, Åsa Segerstolpe1,2,5, Elisabeth Raschperger1,2, Emil M. Hansson1,2, Johan L. M. Björkegren 1,2,6, Xiao-Rong Peng7, ✉ Michael Vanlandewijck1,2,4, Urban Lendahl1,8 & Christer Betsholtz 1,2,4 1234567890():,; Many important cell types in adult vertebrates have a mesenchymal origin, including fibro- blasts and vascular mural cells. Although their biological importance is undisputed, the level of mesenchymal cell heterogeneity within and between organs, while appreciated, has not been analyzed in detail. Here, we compare single-cell transcriptional profiles of fibroblasts and vascular mural cells across four murine muscular organs: heart, skeletal muscle, intestine and bladder. We reveal gene expression signatures that demarcate fibroblasts from mural cells and provide molecular signatures for cell subtype identification. We observe striking inter- and intra-organ heterogeneity amongst the fibroblasts, primarily reflecting differences in the expression of extracellular matrix components. Fibroblast subtypes localize to discrete anatomical positions offering novel predictions about physiological function(s) and regulatory signaling circuits. Our data shed new light on the diversity of poorly defined classes of cells and provide a foundation for improved understanding of their roles in physiological and pathological processes. 1 Karolinska Institutet/AstraZeneca Integrated Cardio Metabolic Centre, Blickagången 6, SE-14157 Huddinge, Sweden. -

Genetic Defects in B-Cell Development and Their Clinical Consequences H Abolhassani,1,2 N Parvaneh,1 N Rezaei,1 L Hammarström,2 a Aghamohammadi1

REVIEWS Genetic Defects in B-Cell Development and Their Clinical Consequences H Abolhassani,1,2 N Parvaneh,1 N Rezaei,1 L Hammarström,2 A Aghamohammadi1 1Research Center for Immunodeficiencies, Pediatrics Center of Excellence, Children’s Medical Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 2Division of Clinical Immunology, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institutet at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge, Stockholm, Sweden n Abstract Expression of selected genes in hematopoietic stem cells has been identified as a regulator of differentiation of B cells in the liver and bone marrow. Moreover, naïve B cells expressing surface immunoglobulin need other types of genes for antigen-dependent development in secondary lymphoid organs. Many advanced molecular mechanisms underlying primary antibody deficiencies in humans have been described. We provide an overview of the mutations in genes known to be involved in B-cell development and their clinical consequences. Key words: Genetic disorder. B-cell development. Primary antibody deficiencies. Clinical phenotypes. n Resumen Se ha identificado la expresión de genes seleccionados en las células pluripotenciales de médula ósea como reguladores de la diferenciación de las células B en el hígado y en médula ósea. Sin embargo, las células B naïve que expresan inmunoglubulinas de superficie, necesitan otros tipos de genes para su desarrollo en los órganos linfoides secundarios dependienteS de antígeno. Se han descrito muchos mecanismos moleculares avanzados que subrayan las inmunodeficiencias en humanos y esta revisión constituye una visión general de la mutación en todos los genes conocidos involucrados en el desarrollo de las células B y sus consecuencias clínicas. Palabras clave: Alteraciones genéticas. Desarrollo de las células B. -

Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Transmembrane Targets on Transplantable Midbrain Dopamine Progenitors

Transcriptome analysis reveals transmembrane targets on transplantable midbrain dopamine progenitors Chris R. Byea, Marie E. Jönssonb, Anders Björklundb,1, Clare L. Parisha, and Lachlan H. Thompsona,1 aFlorey Institute for Neuroscience and Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia 3010; and bWallenberg Neuroscience Centre, Department of Experimental Medical Science, Lund University, S-22184 Lund, Sweden Contributed by Anders Björklund, February 5, 2015 (sent for review December 8, 2014; reviewed by Eva Hedlund and Tilo Kunath) An important challenge for the continued development of cell targeting of cell-specific surface antigens as a means to separate therapy for Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the establishment of proce- defined cell fractions from mixed populations. Central to the dures that better standardize cell preparations for use in transplan- development of the technique was the identification of trans- tation. Although cell sorting has been an anticipated strategy, its membrane proteins that selectively define a target cell population. + + application has been limited by lack of knowledge regarding trans- For example, isolation of CD34 and Thy1 cells facilitates puri- membrane proteins that can be used to target and isolate progen- fication of hematopoietic stem cells that can reconstitute the he- itors for midbrain dopamine (mDA) neurons. We used a “FACS-array” matopoietic system as part of treatment for cancer patients (7–10). approach to identify 18 genes for transmembrane proteins with A current obstacle for the development of similar techniques for high expression in mDA progenitors and describe the utility of four the purification of specific neural progenitor phenotypes, in- of these targets (Alcam, Chl1, Gfra1, and Igsf8) for isolating mDA cluding mDA progenitors, is a lack of knowledge regarding the progenitors from rat primary ventral mesencephalon through flow identity of suitable transmembrane targets. -

Human Perivascular Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Mediate Bone

RESEARCH ARTICLE Human perivascular stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles mediate bone repair Jiajia Xu1, Yiyun Wang1, Ching-Yun Hsu1, Yongxing Gao1, Carolyn Ann Meyers1, Leslie Chang1, Leititia Zhang1,2, Kristen Broderick3, Catherine Ding4, Bruno Peault4,5,6, Kenneth Witwer7,8, Aaron Watkins James1* 1Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States; 2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Stomatology, China Medical University, Shenyang, China; 3Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States; 4Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Orthopaedic Hospital Research Center, UCLA, Orthopaedic Hospital, Los Angeles, United States; 5Centre For Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom; 6MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom; 7Department of Molecular and Comparative Pathobiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States; 8Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States Abstract The vascular wall is a source of progenitor cells that are able to induce skeletal repair, primarily by paracrine mechanisms. Here, the paracrine role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in bone healing was investigated. First, purified human perivascular stem cells (PSCs) were observed to induce mitogenic, pro-migratory, and pro-osteogenic effects on osteoprogenitor cells while in non- contact co-culture via elaboration of EVs. PSC-derived EVs shared mitogenic, pro-migratory, and pro-osteogenic properties of their parent cell. PSC-EV effects were dependent on surface- associated tetraspanins, as demonstrated by EV trypsinization, or neutralizing antibodies for CD9 or CD81. Moreover, shRNA knockdown in recipient cells demonstrated requirement for the CD9/ CD81 binding partners IGSF8 and PTGFRN for EV bioactivity. Finally, PSC-EVs stimulated bone repair, and did so via stimulation of skeletal cell proliferation, migration, and osteodifferentiation. -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Engineered Type 1 Regulatory T Cells Designed for Clinical Use Kill Primary

ARTICLE Acute Myeloid Leukemia Engineered type 1 regulatory T cells designed Ferrata Storti Foundation for clinical use kill primary pediatric acute myeloid leukemia cells Brandon Cieniewicz,1* Molly Javier Uyeda,1,2* Ping (Pauline) Chen,1 Ece Canan Sayitoglu,1 Jeffrey Mao-Hwa Liu,1 Grazia Andolfi,3 Katharine Greenthal,1 Alice Bertaina,1,4 Silvia Gregori,3 Rosa Bacchetta,1,4 Norman James Lacayo,1 Alma-Martina Cepika1,4# and Maria Grazia Roncarolo1,2,4# Haematologica 2021 Volume 106(10):2588-2597 1Department of Pediatrics, Division of Stem Cell Transplantation and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA; 2Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA; 3San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Milan, Italy and 4Center for Definitive and Curative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA *BC and MJU contributed equally as co-first authors #AMC and MGR contributed equally as co-senior authors ABSTRACT ype 1 regulatory (Tr1) T cells induced by enforced expression of interleukin-10 (LV-10) are being developed as a novel treatment for Tchemotherapy-resistant myeloid leukemias. In vivo, LV-10 cells do not cause graft-versus-host disease while mediating graft-versus-leukemia effect against adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Since pediatric AML (pAML) and adult AML are different on a genetic and epigenetic level, we investigate herein whether LV-10 cells also efficiently kill pAML cells. We show that the majority of primary pAML are killed by LV-10 cells, with different levels of sensitivity to killing. Transcriptionally, pAML sensitive to LV-10 killing expressed a myeloid maturation signature. -

Table S3. RAE Analysis of Well-Differentiated Liposarcoma

Table S3. RAE analysis of well-differentiated liposarcoma Model Chromosome Region start Region end Size q value freqX0* # genes Genes Amp 1 145009467 145122002 112536 0.097 21.8 2 PRKAB2,PDIA3P Amp 1 145224467 146188434 963968 0.029 23.6 10 CHD1L,BCL9,ACP6,GJA5,GJA8,GPR89B,GPR89C,PDZK1P1,RP11-94I2.2,NBPF11 Amp 1 147475854 148412469 936616 0.034 23.6 20 PPIAL4A,FCGR1A,HIST2H2BF,HIST2H3D,HIST2H2AA4,HIST2H2AA3,HIST2H3A,HIST2H3C,HIST2H4B,HIST2H4A,HIST2H2BE, HIST2H2AC,HIST2H2AB,BOLA1,SV2A,SF3B4,MTMR11,OTUD7B,VPS45,PLEKHO1 Amp 1 148582896 153398462 4815567 1.5E-05 49.1 152 PRPF3,RPRD2,TARS2,ECM1,ADAMTSL4,MCL1,ENSA,GOLPH3L,HORMAD1,CTSS,CTSK,ARNT,SETDB1,LASS2,ANXA9, FAM63A,PRUNE,BNIPL,C1orf56,CDC42SE1,MLLT11,GABPB2,SEMA6C,TNFAIP8L2,LYSMD1,SCNM1,TMOD4,VPS72, PIP5K1A,PSMD4,ZNF687,PI4KB,RFX5,SELENBP1,PSMB4,POGZ,CGN,TUFT1,SNX27,TNRC4,MRPL9,OAZ3,TDRKH,LINGO4, RORC,THEM5,THEM4,S100A10,S100A11,TCHHL1,TCHH,RPTN,HRNR,FLG,FLG2,CRNN,LCE5A,CRCT1,LCE3E,LCE3D,LCE3C,LCE3B, LCE3A,LCE2D,LCE2C,LCE2B,LCE2A,LCE4A,KPRP,LCE1F,LCE1E,LCE1D,LCE1C,LCE1B,LCE1A,SMCP,IVL,SPRR4,SPRR1A,SPRR3, SPRR1B,SPRR2D,SPRR2A,SPRR2B,SPRR2E,SPRR2F,SPRR2C,SPRR2G,LELP1,LOR,PGLYRP3,PGLYRP4,S100A9,S100A12,S100A8, S100A7A,S100A7L2,S100A7,S100A6,S100A5,S100A4,S100A3,S100A2,S100A16,S100A14,S100A13,S100A1,C1orf77,SNAPIN,ILF2, NPR1,INTS3,SLC27A3,GATAD2B,DENND4B,CRTC2,SLC39A1,CREB3L4,JTB,RAB13,RPS27,NUP210L,TPM3,C1orf189,C1orf43,UBAP2L,HAX1, AQP10,ATP8B2,IL6R,SHE,TDRD10,UBE2Q1,CHRNB2,ADAR,KCNN3,PMVK,PBXIP1,PYGO2,SHC1,CKS1B,FLAD1,LENEP,ZBTB7B,DCST2, DCST1,ADAM15,EFNA4,EFNA3,EFNA1,RAG1AP1,DPM3 Amp 1