Between Modernization and Land Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scrutiny Board

Customer Services Cannards Grave Road, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 5BT Telephone: 0300 303 8588 Fax: 01749 344050 Email: [email protected] www.mendip.gov.uk Scrutiny Board Monday, 17 May 2021 Council Chamber Mendip District Council Cannards Grave Road Shepton Mallet, BA4 5BT 6.30 pm This agenda can be made available in large print and other languages including Braille. Please contact the Committee Officer for details. Lead Officer: Tracy Aarons Tel: 01749 341448 Email: [email protected] Committee Officer: Sarah Gooding Tel : 01749 341341 E-mail : [email protected] Membership: Councillors Chris Inchley (Chair), Barbi Lund (Deputy Chair), Alison Barkshire, Adam Boyden, Nick Cottle, Michael Dunk, Damon Hooton, Janine Nash, Terry Napper, Sam Phripp, Lois Rogers, Lucie Taylor Hood and Nigel Woollcombe-Adams Substitutes: Councillors Eve Berry, John Clarke, Nigel Hewitt-Cooper, Edric Hobbs and Mike Pullin. NB: Whilst formal meetings are returning to Council premises from 7 May 2021, COVID restrictions are still in place. This means that whilst meetings will be open to the public, attendance will be limited. Meetings will be live streamed where at all possible. Please contact the Committee Officer in the first instance should you wish to attend. 1 Notes 1. Length of meeting - Normally the meeting will end when all the business on the agenda has been completed. As soon as this meeting has lasted for three hours the Chair will ask members to vote on whether to end the meeting. There will be a short briefing from officers on implications but no debate on whether the meeting should end. -

TOSSUPS - FLORIDA STATE SWORD BOWL 2005 -- UT-CHATTANOOGA Questions by Billy Beyer with a Few from Bucknell and Boston College

TOSSUPS - FLORIDA STATE SWORD BOWL 2005 -- UT-CHATTANOOGA Questions by Billy Beyer with a few from Bucknell and Boston College EDITOR'S NOTE: This packet originally had a tossup on Jerry Springer: The Opera, which I thought too obscure. But I thought evelyone should know that the opera includes Jesus singing a song titled "Talk to the Stigmata. " 1. An unfinished play of his follows Countess lise and an acting troupe in "The Mountain Giants." His first widely acclaimed novel was "The Late Mattia Pascal", but he made his reputation with plays such as "Right You Are" and "Henry IV." Winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize for Literature, his most famous work is set during a theater rehearsal and is crashed by a family looking for someone to tell their story. For ten points -- name this Italian playwright whose magnum opus is "Six Characters in Search of an Author." Answer: Luigi Pirandello 2. His marriage to Theodora, a former actress, led to many later emperors marrying outside the aristocratic class. Procopius provides a primary source for the history of his reign which featured military expansion that was primarily through the campaigns of Belisarius. His namesake work was largely compiled by his advocate Tribonian, and the Hagia Sophia was rebuilt during his reign. For ten points -- name this Byzantine emperor who ruled from 527-565 CEo Answer: Justinian (gladly accept Flavius Petrus Sabbatius Iustinianus) 3. In Arthur C. Clarke's "Imperial Earth", it is home to a human colony with a population of250,000. Made up of half water ice and half rocky material, this body is home to a large, highly reflective area that has been unofficially named Xanadu. -

Tim Young, Adam Fine, Tricia Southard.Pdf

\ earn name here TRASHMASTERS 2004 - UT-CHATTANOOGA ) Tim Young, Adam Fine, and Tricia Southard , J t-/ILJjl£; // / He led the American League in hits in his rookie season of 1942, but then spent three years fighting in World War / /fI. While with Detroit in 1952, he helped Virgil Trucks record his second no-hitter of the season after admitting that he ,/' misplayed a Phil Rizzuto ball originally called a hit. The goat of the 1946 World Series when he allowed Enos Slaughter / to score, FrP name this Red Sox shortstop, born John Paveskovich, the namesake of the right field foul pole in Fenway Park. Answer: Johnny Pesky 2. The title came about as a catch phrase among band members about what they hoped would happen to people "behaving in a shitty way." The piano riff in the chorus echoes another song about someone acting badly, the Beatles' "Sexy Sadie." The lyrics decry a man who "buzzes like a detuned radio" and a girl with a "Hitler hairdo," and hope that the titular entity will arrest them. We are told in the coda that the narrator "For a minute there . .I lost myself' over and over. FTPname this 1997 song, the third single from "OK Computer," a major hit for Radiohead. Answer: Karma Police 3. A 1979 graduate of Davidson College, this woman won an investigative reporting honor from the North Carolina Press Association for a series of articles about crime and prostitution in Charlotte. Her first book, An Uncommon Friend, was a biography of Billy Graham's wife, but her six years of work for the Virginia Chief Medical Examiner's Office inspired her best know series of a dozen novels. -

Kelis Tasty Full Album Zip

Kelis, Tasty Full Album Zip Kelis, Tasty Full Album Zip 1 / 2 Kelis, Tasty full album zip.. Album · 2014 · 13 Songs. ... Kelis offers a soulful collection of horn-accompanied retro R&B that's conceptually united by her gastronomic passion. ... 2003's ultra-sassy “Milkshake”), but neither the music nor the inspiration for .... Tracklist: 1. Intro, 2. Trick Me, 3. Milkshake, 4. Keep It Down, 5. In Public, 6. Flashback, 7. Protect My Heart, 8. Millionaire, 9. Glow, 10. Sugar Honey Iced Tea, 11.. Caught Out There vk.com/xclusives_zone. 4:51. Kelis. Milkshake vk.com/xclusives_zone. 3:02. Kelis - Kaleidoscope (1999) xclusives_zone.rar.. 'Jerk Ribs' Video from Kelis' album 'Food' - released 21 April 2014 on Ninja Tune. ... One of her standout albums was called Tasty; one of its biggest hits was .... Kelis teased "Food" a full year ago with this brassy, funk-laced jam, which appears .... The Hits is the first greatest hits album by American singer-songwriter Kelis, released on March .... "Kelis Talks 'Milkshake' and 'Tasty' Hits". Blues & Soul.. All The Drake Collaborations We're Still Waiting For. Tasty is the third studio album by American singer Kelis, released on December 5, 2003, via Star… read .... Kelis, Tasty Full Album Zip - DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). kelis tastykelis tasty zipkelis tasty vinylkelis tasty songskelis tasty ituneskelis tasty .... The maverick vocalist and foodie behind the albums Kaleidoscope (1999), Wanderland (2001), the gold-certified Tasty (2003), Kelis Was Here .... Tasty, an Album by Kelis. Released 9 December 2003 on Star Trak (catalog no. 82876-52132-2; CD). Genres: Contemporary R&B. Featured peformers: Kelis ... -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

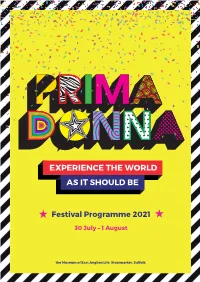

Experience the World As It Should Be

EXPERIENCE THE WORLD AS IT SHOULD BE Festival Programme 2021 30 July – 1 August the Museum of East Anglian Life, Stowmarket, Suffolk 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCING Introduction 3 For Writers 4 PRIMADONNA & THE PRIMADONNAS For the Curious 7 For Fun! 12 The Festival The Founders For Kids 16 Welcome to Primadonna, the UK’s most Primadonna was founded and is run by 17 empowering new festival, set up to spotlight the women from across the worlds of publishing, artistry of women and non-binary people, as well entertainment and the arts. Us ‘Primadonnas’ Event Programme as creatives of all genders, ethnicities and economic wanted to create a festival of brilliant writing, borne status whose voices are not often enough heard. out of a desire to give prominence to work by Friday 18 We focus on writing and reading but we also women and spotlight authors from the margins. showcase the best of the arts, from music to fi lm, We also want you to have a lot of fun: the festival Saturday 20 theatre to comedy. has always been designed to be a thoroughly We call it ‘the world as it should be, for one joyous as well as inclusive and accessible experience. Sunday weekend’. 22 But you know all that: you’re here. And we hope We programme a mix of big names and emerging you’ll agree we’ve put on a programme of amazing talent, as one of the things we’re trying to do is Speakers’ Info 24 speakers, brilliant events and unique experiences. open up the publishing industry and arts/culture more generally to new voices, and new ideas. -

Our Mr. Wrenn: the Romantic Adventures of a Gentle Man

Our Mr. Wrenn: The Romantic Adventures Of A Gentle Man Written in 1914 by Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951) This version originally published in 2005 by Infomotions, Inc. This text originated from a gopher-based Wiretap archive, and it was digitally created by Cardinalis Etext Press in 1993. This document is distributed under the GNU Public License. 1 2 Table of contents Chapter I - Mr. Wrenn Is Lonely Chapter II - He Walks With Miss Theresa Chapter III - He Starts For The Land Of Elsewhere Chapter IV - He Becomes The Great Little Bill Wrenn Chapter V - He Finds Much Quaint English Flavor Chapter VI - He Is An Orphan Chapter VII - He Meets A Temperament Chapter VIII - He Tiffins Chapter IX - He Encounters The Intellectuals Chapter X - He Goes A-Gipsying Chapter XI - He Buys An Orange Tie Chapter XII - He Discovers America Chapter XIII - He Is "Our Mr. Wrenn" Chapter XIV - He Enters Society Chapter XV - He Studies Five Hundred, Savouir Faire, And Lotsa-Snap Office Mottoes Chapter XVI - He Becomes Mildly Religious And Highly Literary Chapter XVII - He Is Blown By The Whirlwind Chapter XVIII - And Follows A Wandering Flame Through Perilous Seas Chapter XIX - To A Happy Shore 3 4 To Grace Livingstone Hegger 5 6 Chapter I - Mr. Wrenn Is Lonely The ticket-taker of the Nickelorion Moving-Picture Show is a public personage, who stands out on Fourteenth Street, New York, wearing a gorgeous light-blue coat of numerous brass buttons. He nods to all the patrons, and his nod is the most cordial in town. Mr. Wrenn used to trot down to Fourteenth Street, passing ever so many other shows, just to get that cordial nod, because he had a lonely furnished room for evenings, and for daytime a tedious job that always made his head stuffy. -

The Spectral Voice and 9/11

SILENCIO: THE SPECTRAL VOICE AND 9/11 Lloyd Isaac Vayo A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Eileen C. Cherry Chandler Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Don McQuarie © 2010 Lloyd Isaac Vayo All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor “Silencio: The Spectral Voice and 9/11” intervenes in predominantly visual discourses of 9/11 to assert the essential nature of sound, particularly the recorded voices of the hijackers, to narratives of the event. The dissertation traces a personal journey through a selection of objects in an effort to seek a truth of the event. This truth challenges accepted narrativity, in which the U.S. is an innocent victim and the hijackers are pure evil, with extra-accepted narrativity, where the additional import of the hijacker’s voices expand and complicate existing accounts. In the first section, a trajectory is drawn from the visual to the aural, from the whole to the fragmentary, and from the professional to the amateur. The section starts with films focused on United Airlines Flight 93, The Flight That Fought Back, Flight 93, and United 93, continuing to a broader documentary about 9/11 and its context, National Geographic: Inside 9/11, and concluding with a look at two YouTube shorts portraying carjackings, “The Long Afternoon” and “Demon Ride.” Though the films and the documentary attempt to reattach the acousmatic hijacker voice to a visual referent as a means of stabilizing its meaning, that voice is not so easily fixed, and instead gains force with each iteration, exceeding the event and coming from the past to inhabit everyday scenarios like the carjackings. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Kelis Tasty Full Album Zip

Kelis, Tasty Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Kelis, Tasty Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Kelis' debut, the 1999 Kaleidoscope was a bizarre left-field masterpiece, with ... metaphors, and whatever other bizarre notion happened to zip across her skull. ... but the album as a whole really wasn't angry— it was exuberant. ... with on 2003's Tasty, on 2006's bloated Kelis Was Here…and most recently .... Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for Wanderland - Kelis on AllMusic - 2001 - Wanderland unfortunately didn't build on the…. Tasty, an Album by Kelis. Released 9 December 2003 on Star Trak (catalog no. 82876-52132-2; CD). Genres: Contemporary R&B. Featured peformers: Kelis .... Listen free to Kelis – Tasty (Intro, Trick Me and more). ... Tasty is the third studio album by American singer-songwriter Kelis, released on ... View full artist profile .... Caught Out There vk.com/xclusives_zone. 4:51. Kelis. Milkshake vk.com/xclusives_zone. 3:02. Kelis - Kaleidoscope (1999) xclusives_zone.rar.. The Hits is the first greatest hits album by American singer-songwriter Kelis, released on March .... "Kelis Talks 'Milkshake' and 'Tasty' Hits". Blues & Soul.. 'Jerk Ribs' Video from Kelis' album 'Food' - released 21 April 2014 on Ninja Tune. ... One of her standout albums was called Tasty; one of its biggest hits was .... Kelis teased "Food" a full year ago with this brassy, funk-laced jam, which appears .... All The Drake Collaborations We're Still Waiting For. Tasty is the third studio album by American singer Kelis, released on December 5, 2003, via Star… read .... Kelis, Tasty full album zip. -

Előadó Album Címe a Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- a Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi

Előadó Album címe A Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- A Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi.. A Fine Frenzy Bomb In a Birdcage A Flock of Seagulls Best of -12tr- A Flock of Seagulls Playlist-Very Best of A Silent Express Now! A Tribe Called Quest Collections A Tribe Called Quest Love Movement A Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Trav Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothin' But a N Ab/Cd Cut the Crap! Ab/Cd Rock'n'roll Devil Abba Arrival + 2 Abba Classic:Masters.. Abba Icon Abba Name of the Game Abba Waterloo + 3 Abba.=Tribute= Greatest Hits Go Classic Abba-Esque Die Grosse Abba-Party Abc Classic:Masters.. Abc How To Be a Zillionaire+8 Abc Look of Love -Very Best Abyssinians Arise Accept Balls To the Wall + 2 Accept Eat the Heat =Remastered= Accept Metal Heart + 2 Accept Russian Roulette =Remaste Accept Staying a Life -19tr- Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Adem-Het Beste Van Acda & De Munnik Live Met Het Metropole or Acda & De Munnik Naar Huis Acda & De Munnik Nachtmuziek Ace of Base Collection Ace of Base Singles of the 90's Adam & the Ants Dirk Wears White Sox =Rem Adam F Kaos -14tr- Adams, Johnny Great Johnny Adams Jazz.. Adams, Oleta Circle of One Adams, Ryan Cardinology Adams, Ryan Demolition -13tr- Adams, Ryan Easy Tiger Adams, Ryan Love is Hell Adams, Ryan Rock'n Roll Adderley & Jackson Things Are Getting Better Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball's Bossa Nova Adderley, Cannonball Inside Straight Adderley, Cannonball Know What I Mean Adderley, Cannonball Mercy