By Brad Newsham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tapemaster Main Copy

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to January 2018 2018 Daniel Pink When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing 1/18/18 Martin Shiel WhoWhatWhy Story on Deutsche Bank 1/17/18 Sara Zaske Achtung Baby: An American Mom on the German Art of Raising Self-Reliant Children 1/17/18 Frances Moore Lappe Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning and Connection for the America We Want 1/16/18 Martin Puchner The Written Word: The Power of Stories to Shape People, History, Civilization 1/11/18 Sarah Kendzior Author /Journalist “The View From Flyover Country” 1/11/18 Gordon Whitman Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out and Win in a World on Fire 1/10/18 Brian Dear The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture 1/9/18 Valter Longo The Longevity Diet: The New Science behind Stem Cell Activation 1/9/18 Richard Haass The World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order 1/8/18 Chloe Benjamin The Immortalists: A Novel 1/5/18 2017 Morgan Simon Real Impact: The New Economics of Social Change 12/20/17 Daniel Ellsberg The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a War Planner 12/19/17 Tom Kochan Shaping the Future of Work: A Handbook for Action and a New Social Contract 12/15/17 David Patrikarakos War in 140 Characters: How Social Media is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty First Century 12/14/17 Gary Taubes The Case Against Sugar 12/13/17 Luke Harding Collusion: Secret Meetins, Dirty Money and How Russia Helped Donald Trump Win 12/13/17 Jake Bernstein Secrecy World: Inside the Panama Papers -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

Summer 2020, Issue No

SUMMER ’20 SUSTAINABILITY Is a Promise 34 36 41 Rich Block: Counting Eagles A Civil War of Words Snapshots from Spring Semester: and Charting a Career Studying and Teaching from Home Get to know Principia today. MIDDLE / UPPER SCHOOL Visiting Weekends Across both campuses, we are • September 26–28 • February 13–15 preparing students to be future- • October 24–26 • February 27–March 1 ready leaders who use their • November 14–16 • April 10–12 • January 23–25 • April 24–26 education for the greater good. Applications for fall 2020 are being accepted until July 15. As we challenge students to principiaschool.org/visit pursue innovation and embrace challenge, we, too, are looking Families with younger children are welcome for day visits anytime during the school year. ahead and envisioning new opportunities for Principia to fulfill its mission. Experience today’s Principia! Learn how we’re building on our founding principles to ensure a robust future. Our Travel Fund is available to help with a portion of transportation costs. COLLEGE Visiting Weekends Give us a call—we’d love to chat! • September 24–27 • February 18–21 School: 314.514.3188 • October 8–11 • March 25–28 • October 22–25 • April 8–11 College: 618.374.5578 • November 5–8 • April 22–25 Know someone we should invite to visit? Let us know at principia.edu/referastudent. principiacollege.edu/visit From the Interim Chief Executive Summer 2020, Issue No. 382 The mission of the Principia Purpose is to build Dear Reader, community among alumni and friends by shar- ing news, accomplishments, and insights related to Principia, its alumni, and faculty and staff. -

Planning Curriculum in International Education. INSTITUTION Wisconsin State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 600 SO 035 279 AUTHOR Durtka, Sharon; Dye, Alex; Freund, Judy; Harris, Jay; Kline, Julie; LeBreck, Carol; Reimbold, Rebecca; Tabachnick, Robert; Tantala, Renee; Wagler, Mark TITLE Planning Curriculum in International Education. INSTITUTION Wisconsin State Dept. of Public Instruction, Madison. REPORT NO Bull-3033 ISBN ISBN-1-57337-102-5 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 361p. AVAILABLE FROM Publications Sales, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, Drawer 179, Milwaukee, WI 53293-0179. Tel: 800- 243-8782 (Toll Free); Tel: 608-266-2188; Fax: 608-267-9110; Web site: http://www.dpi.state.wi.us/pubsales. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Standards; *Curriculum Development; *Demonstration Programs; Elementary Secondary Education; *Global Education; *International Education; Public Schools; Social Studies; State Standards IDENTIFIERS *Global Issues; *Wisconsin ABSTRACT International education begins at home, in the very communities and environments most familiar to students. A student does not need to travel outside U.S. borders to meet the peoples or understand the issues of the global village. This planning guide shows how curriculum in all subject areas encompasses global challenges, global cultures, and global connections. The guide is based on work taking place in Wisconsin classrooms and takes its lead from Wisconsin's Model Academic Standards. Wisconsin's heritage cultures are part of the fabric of the guide, and they weave their way through all its -

Off to a Roaring Start Young Alumni Make Their Mark

PURPOSEWINTER ’18 OFF TO A ROARING START YOUNG ALUMNI MAKE THEIR MARK 38 42 46 What’s Next? Crafting a Culture of The New Voney Art Center Internships and Summer Collaboration and Excellence in Is Open! Research Help Provide Answers Middle School Know Someone Who Should Visit Principia? The best way for prospective students and their parents to get a feel for Principia is to visit—explore campus, sit in on classes, meet students, and make themselves at home. In many cases, we’ll even cover most of the airfare! Middle and Upper School College Visiting Weekends Visiting Weekends Spring Semester 2018 • February 22–25 Spring Semester 2018 • March 8–11 • January 20–22 • March 29–April 1 • February 17–19 • April 26–29 • March 3–5 • April 7–9 Parent visit days are offered during each • April 21–23 Visiting Weekend. Independent visits are available as well. Independent visits are also offered at all School levels. Give us a call—we’d love to chat! School: 314.514.3142 | College: 618.374.5187 Or contact us online to let us know of any family or friends we should invite to visit. principia.edu/referastudent PURPOSE From the Chief Executive Winter 2018, Issue No. 377 The mission of the Principia Purpose is to build community among alumni and friends Dear Reader, by sharing news, accomplishments, and insights related to Principia, its alumni, and former faculty and staff. The Principia Purpose is published twice a year. Few things matter more at Principia—or are more rewarding—than to see young alumni thriving in the Marketing and Communications Director Laurel Shaper Walters (US’84) world. -

Nyhavywe Secret Scrolls of the Warrior Sage, Stephen K. Hayes

nyhavywe Secret Scrolls of the Warrior Sage, Stephen K. Hayes , 2007, 089750156X, 9780897501569. The sixth and final installment of this best-selling series provides the insight and wisdom garnered from the author's four decades of martial arts training. The inspirational and legendary master demonstrates scores of techniques with in-depth captions and detailed photos, describes the experiences that made him an internationally recognized warrior and educator, and discusses how to avoid attitude problems and training plateaus in any martial art. One continuous picnic: a history of eating in Australia, Michael Symons , 1982, 0959304703, 9780959304701. Leelore's Unusual Choir, , 2000, 096214441X, 9780962144417. A Clenched Fist: The Making of a Golden Gloves Champion, Peter Weston Wood , 2007, 0978968301, 9780978968304. GRABBING A GOLDEN DREAM WITH GOLDEN GLOVES Does boxing teach anything besides how to club someone into submission? Can it transcend its sordid reputation and instill love, compassion and honor in Americas most troubled kids? In this raw yet uplifting memoir about amateur boxing, author Peter Wood tells of his begrudging return to a world he thought hed left behind. He steps back into the mud of boxing, coaching two troubled teens who dreamas he once didof becoming Golden Gloves champions.His compelling story moves far beyond the grunt and sweat of the local gym. It explores the classrooms of a suburban high school and digs through the remains of unhappy childhoods. Its a story about how boxing is a way out, and how it cleanses the soul.This book brings the subculture of amateur boxing up close and weaves a powerful story of redemption, beating demons and battling for glory. -

The Fixer a Theory in Forms Book

The Fixer A Theory in Forms book Series Editors Nancy Rose Hunt and Achille Mbembe The Fixer VISA LOTTERY CHRONICLES Charles Piot with Kodjo Nicolas Batema Duke University Press Durham & London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro, New Century Schoolbook, and Bickham Script Pro by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Piot, Charles, author. | Batema, Kodjo Nicolas (Visa broker), author. Title: The fixer : visa lottery chronicles / Charles Piot ; with Kodjo Nicolas Batema. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: A theory in forms book | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2018047216 (print) | lccn 2019005119 (ebook) isbn 9781478003427 (ebook) isbn 9781478001911 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478003045 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: African diaspora. | Batema, Kodjo Nicolas (Visa broker) | Togo— Emigration and immigration. | Visas—Togo. | Togolese—Migrations—History— 21st century. | Togolese—United States. | Visas—Government policy—United States. | Emigration and immigration law—United States. Classification:lcc dt16.5 (ebook) | lcc dt16.5 .P49 2019 (print) | ddc 304.8/7306681—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047216 Cover art: Kodjo, the Fixer, in his office. Photo courtesy of the author. Publication of this open monograph was the result of Duke University’s participation in tome (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem), a collaboration of the Association of American Uni- versities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries. tome aims to expand the reach of long- form humanities and social science scholarship including digi- tal scholarship. -

Exploring Science: Eclipses, Orchards, Exoplanets

PURPOSESUMMER ’17 EXPLORING SCIENCE: ECLIPSES, ORCHARDS, EXOPLANETS 36 43 44 Q&A with Chief Executive School Performing Arts Meet a Few of This Marshall Ingwerson Center Opens Year’s Graduates Know Someone Who Should Visit Principia? The best way for prospective students and their parents to get a feel for Principia is to visit—explore campus, sit in on classes, meet students, and make themselves at home. In many cases, we’ll even cover most of the airfare! Middle and Upper School College Visiting Weekends Visiting Weekends Fall 2017 Fall 2017 • October 12–15 • September 23–25 • October 26–29 • October 28–30 • November 9–12 • November 11–13 • November 30–December 3 Adriane M. Fredrikson Tami Gavaletz School Director of Admissions College Director of Admissions 314.514.3130 618. 374.5187 Contact us online to let us know of any family or friends we should invite to visit. Or give us a call—we’d love to chat! www.principia.edu/contact-us PURPOSE From the Chief Executive SUMMER 2017, Issue No. 376 The mission of the Principia Purpose is to Dear Reader, build community among alumni and friends by sharing news, updates, accomplishments, and insights related to Principia, its alumni, and former faculty and staff. The Principia As I’ve read the Purpose over the years, the wide, global Purpose is published twice a year. scope of Principia and Principians has always been appar- Marketing and Communications Director ent in its pages. Now that I have an insider’s view of Laurel Shaper Walters (US’84) what students and alumni are doing, I see more vividly Associate Marketing Director how remarkable this range of impacts and activities is— Kathy Coyne (US’83, C’87) both on and off campus. -

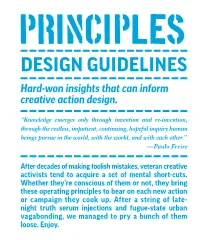

DESIGN GUIDELINES Hard-Won Insights That Can Inform Creative Action Design

PRINCIPLES DESIGN GUIDELINES Hard-won insights that can inform creative action design. “Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.” —Paulo Freire After decades of making foolish mistakes, veteran creative activists tend to acquire a set of mental short-cuts. Whether they’re conscious of them or not, they bring these operating principles to bear on each new action or campaign they cook up. After a string of late- night truth serum injections and fugue-state urban vagabonding, we managed to pry a bunch of them loose. Enjoy. PRINCIPLE: Anger works best when you have the moral high ground IN SUM Anger is a double-edged sword. Or perhaps it’s more like Anger is potent. Use it a water hose: it’s full of force, it’s hard to control, and it’s wisely. If you have the important where you aim it. moral higher ground, it is There is a crucial distinc- “Integrity gives compelling and people tion to be made between moral will join you. If you don’t, you’ll indignation and self-righteous- deep meaning look like a cranky wing-nut. ness. Moral indignation chan- and moral force to nels anger into resolve, courage EPIGRAPH and powerful assertions of anger. We should “The truth will set you free, dignity. Think: the civil rights movement. Self-righteousness, on never come o but rst it will piss you o¡.” the other hand, is predictable —Gloria Steinem as mad-for-the- and easily dismissed. -

Northern News

NORTHERN NEWS American Planning Association A Publication of the Northern Section of the California Chapter of APA DECEMBER 2013/JANUARY 2014 Making Great Communities Happen Exurban and super-high density Turkey’s hills are alive with the sound of building By Jennifer Piozet, associate editor This past November, I attended a for redevelopment as the land is sold by the government meeting of the Santa Clara County to private investors. Housing Action Coalition (HAC) “Drive through a suburb out to the hills beyond Ankara, where specific Turkish housing and all of a sudden there are 10 high-rise buildings,” said developments and problems were Shiloh Ballard. You see “an island of really super high discussed. Presenters included Shiloh density residential in the middle of nowhere.” Ballard, Ballard of the HAC and Peter Hamilton, City of San Jose head of the Silicon Valley Housing Action Coalition (both visited Turkey in July); Cigdem Cogur, an Istanbul native and Oakland-based architect for Cogur Design + Construction; and Yelda Kizildag, a Turkish planner who is focusing her PhD dissertation on urban renewal in Istanbul. The following is my summary of the presentation and discussion. But first, a definition: ge•ce•kon•du (gih•zhee•kawn’duh) Turkish, n. 1. literal: was made at night. 2. a makeshift, uncom- fortable hut erected overnight on land owned by the state, municipality, or individuals in defiance of building codes and property rights. 3. a large unplanned community of such dwellings, of various degrees of permanence (cf. favelas, Brazil). [The Genesis of the Gecekondu: Rural Migration and Urbanization (1976), Kemal H.