Policy Space: What, for What, and Where?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structural Change in the World Economy and Forms of Protectionism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Altvater, Elmar Article — Digitized Version Structural change in the world economy and forms of protectionism Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Altvater, Elmar (1988) : Structural change in the world economy and forms of protectionism, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Verlag Weltarchiv, Hamburg, Vol. 23, Iss. 6, pp. 286-296, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02925126 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/140159 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu PROTECTIONISM Elmar Altvater* Structural Change in the World Economy and Forms of Protectionism Warnings about the dangers of protectionism are being heard from a// sides at present. However, rehearsing the advantages of free trade and the drawbacks of protectionism is to/itt/e avai/ if it fai/s to take account of the/imitations that the internationa/ context imposes on nationa/ economic po/icy. -

A. the GATT and the BWI

International Organizations Law Review 3: 267–315, 2006 ©2006 Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY-MAKING: EXPLORING THE LEGAL LINKAGES BETWEEN THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION AND THE BRETTON WOODS INSTITUTIONS JAN WOUTERS1 AND DOMINIC COPPENS2 This contribution aims to shed some light upon the legal relationship between the three main pillars of the international economic architecture: the World Trade Organization (WTO), and its predecessor the GATT 1947, focusing on trade; the International Monetary Fund (IMF or Fund), guarding international monetary and financial stability; and the World Bank, specializing in the field of development. We will examine various aspects of the legal interactions between, on the one hand, the GATT/WTO, and, on the other hand, the IMF and the World Bank, labeled as the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWI). The general legal linkages between the three institutions are first of all explored from a historical perspec- tive (Section I). Section II elaborates upon the different levels of consultation between the WTO and BWI, whereas Section III discusses the involvement of the WTO and BWI in the deliverance of Aid for Trade, which by definition raises interesting questions of collaboration between aid and trade institutions. Finally, various aspects of the legal interactions between the WTO and the BWI are analysed more in depth (Section IV), namely, (i) the relationship between BWI programmes and WTO rules (the substantive level), and (ii) the role of the BWI in the dispute settlement -

A Patchwork Planet 29

patchwork A planet beneficial co-operation of governance. If so, you are likely find- The Covid-19 crisis has exposed the ing the coronavirus crisis even more depressing. From Donald arbitrary way in which we have stitched Trump’s branding of the disease as a specifically “Chinese virus” and his defunding of the World Health Organisation (WHO), to globalisation together. It’s time to go the violation of rules about sharing medical data and an unseemly back to first principles, and tailor a new scramble to secure masks and ventilators amid unilateral export restrictions, there is scant sign of global harmony just now. set of international rules around them The irony, of course, is that at the same time the virus risks setting globalisation (as we have conventionally understood it) spinning into reverse, it is also affirming anew our shared fate dani rodrik as human beings. That might seem like a paradox, but in fact our present-day globalisation is not and never has been the only way—or the best way—of meshing together our economies and other interests. And it is not only scholars in ivory towers who are wondering if this is a moment for a reset. hat do you think of when you hear the word “glo- President Macron of France is both a determined economic balisation?” It might well be the usual newspa- liberal and former investment banker, and yet he used a major per illustration—the container ship that moves interview with the Financial Times in April to concede that amid merchandise round the world. -

English Geneva, 19 May 1998

WORLD TRADE WT/FIFTY/H/ST/1 19 May 1998 ORGANIZATION (98-2004) 50th ANNIVERSARY Original: English Geneva, 19 May 1998 SINGAPORE Statement circulated by H.E. Mr. Goh Chok Tong Prime Minister The Multilateral Trading System: Challenges and opportunities 1. This is an important occasion to toast the success as well as ponder over the future of the multilateral trading system. 2. Together with the Bretton Woods Institutions, the GATT has provided the foundation for post-war global prosperity. Through a non-discriminatory system of rules governing international trade, it has underpinned the robust post-war growth in trade and output. Without the multilateral trading system, the world would not be as prosperous as it is today, nor as peaceful. 3. The benefits of multilateral trade cannot be evenly spread by decree. Each country has to compete for its share of the benefits through its own hard work, efficiency and competitiveness. Competition is tough, but every country can find some areas where they can do well. 4. Developing countries have shown this to be true. Over the past decade, their share of world trade has increased from 20 per cent to 25 per cent, while their share of trade in manufactured goods has doubled from 10 per cent to 20 per cent. 5. The remarkable success of the GATT, however, is rather recent history. The “beggar-thy-neighbour” policies that were pursued duringthe inter-war period broughtdisaster to world trade and the global economy and contributed to the 2nd World War. The most-favoured-nation principle is very much a post-war phenomenon. -

A) the Economic Rationale for Trade Net Effect on the Terms-Of-Trade, but Lead to a Agreements Contraction of Trade Volumes Which Reduces Overall Welfare (See Box 1

II – B FLEXIBILITY IN TRADE AGREEMENTS B FLEXIBILITY IN TRADE AGREEMENTS The aim of this section is to: (a) clarify what Economists have identified several rationales for justifies the inclusion of contingency measures in the existence of trade agreements, such as those trade agreements; (b) provide an account of all embodied in the WTO, and its antecedent, the circumstances when a suspension of commitments General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). may make economic sense; and (c) identify the Two main approaches can be distinguished.1 The flexibility measures built into WTO agreements. first states that in the absence of a trade agreement, The section provides a framework for the discussion a country may be tempted to manipulate the of specific contingency measures in the subsequent terms-of-trade (i.e. the price of its exports relative sections of the Report. to its imports) in order to increase its national income at the expense of its trading partners. The 1. ECONOMIC THEORIES OF second approach stresses the economic and political TRADE AGREEMENTS AND THE difficulties that governments face in setting trade policy. As discussed below, trade agreements allow ROLE OF FLEXIBILITIES governments to escape terms-of-trade conflicts and/ or to resist pressures from the private sector and Trade agreements aim to strike a balance between special-interest groups urging the government to flexibility and commitments. If there is too deviate from a liberal trade policy. much flexibility, the value of the commitment is undermined. If there is too little flexibility, countries i) The traditional approach to trade agreements may refuse to make deep commitments or may easily renege on such commitments. -

Beggar Thy Neighbour: Exchange Rate Regime Misadvice from Misunderstandings of Mundell (1961)

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Pope, Robin Working Paper Beggar Thy Neighbour: Exchange Rate Regime Misadvice from Misunderstandings of Mundell (1961) Bonn Econ Discussion Papers, No. 1/2007 Provided in Cooperation with: Bonn Graduate School of Economics (BGSE), University of Bonn Suggested Citation: Pope, Robin (2007) : Beggar Thy Neighbour: Exchange Rate Regime Misadvice from Misunderstandings of Mundell (1961), Bonn Econ Discussion Papers, No. 1/2007, University of Bonn, Bonn Graduate School of Economics (BGSE), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/22976 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Currency Wars: “Beggar Thy Neighbour” Policy

Currency Wars: “Beggar Thy Neighbour” Policy What is a Currency War? A currency war is a situation wherein devaluation of currency by one country is retaliated by a competitive devaluation from the other country. For instance, if the United States were to devalue the dollar against the Pound Sterling and if the British retaliated with their own devaluation then the situation could be accurately described as a currency war. Devaluation is believed to cause growth in the short run. However, this growth comes at the expense of one’s trading partners. Hence currency wars are also known as “beggar thy neighbour” policy! What Happens When a Currency is Devalued? The devaluation of a currency has multiple effects. Usually they are considered good for the economy in the short run since they increase chances of growth. However, the growth happens at the expense of other economies. Some benefits that arise due to devaluation are as follows: . A cheaper currency makes exports cheaper. Hence, when countries devalue their currency, they end up pricing their products attractively in the international market and as a result end up giving a major impetus to exports even if other factors such as productivity remain constant. A devalued currency also helps to stem imports since the goods produced by other countries tend to become more expensive as compared to domestic goods. Thus, the exports of other nations are negatively affected by currency devaluation. Since higher exports means higher production and therefore implies higher employment, currency devaluation seems like an effective mechanism to control unemployment in the nation. -

Eurozone Crisis: Beggar Thyself and Thy Neighbour

EUROZONE CRISIS: BEGGAR THYSELF AND THY NEIGHBOUR C. Lapavitsas, A. Kaltenbrunner, D. Lindo, J. Michell, J.P. Painceira, E. Pires, J. Powell, A. Stenfors, N. Teles www.researchonmoneyandfinance.org RMF occasional report MARCH 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report has drawn on continuous debate within RMF. Particular thanks are due to G. Dymski, G. Labrinidis, I. Levina, P. Dos Santos, E. Stockhammer, A. Storey, and J. Toporowski for comments on earlier drafts. All responsibility for errors lies with the authors. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 BACKGROUND 1 THE MECHANISMS OF CRISIS 2 ALTERNATIVES 3 1. SEVERAL DIMENSIONS OF A PUBLIC DEBT CRISIS: THE REPORT CONDENSED 4 1.1. A CRISIS WITH DEEP ROOTS 4 1.2 INSTITUTIONAL BIAS AND MALFUNCTION IN THE EUROZONE 5 1.3 PERIPHERAL COUNTRIES IN THE SHADOW OF GERMANY 6 1.4 THE IMPACT OF THE CRISIS OF 2007-9 AND THE ROLE OF FINANCE 7 1.5 POLICY OPTIONS FOR PERIPHERAL COUNTRIES 8 1.6 THE STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 12 2. MACROECONOMIC PERFORMANCE: STAGNATION IN GERMANY, BUBBLES IN THE PERIPHERY 13 2.1 GROWTH, UNEMPLOYMENT AND INFLATION 13 2.2. INVESTMENT AND CONSUMPTION 15 2.3 DEBT 18 3. LABOUR REMUNERATION AND PRODUCTIVITY: A GENERAL SQUEEZE, BUT MORE EFFECTIVE IN GERMANY 21 3.1 A RACE TO THE BOTTOM 21 3.2. THE DETERMINANTS OF GERMAN COMPETITIVE SUCCESS 22 3.3. REAL COMPENSATION AND THE SHARE OF LABOUR IN OUTPUT 24 4. INTERNATIONAL TRANSACTIONS: TRADE AND CAPITAL FLOWS IN THE SHADOW OF GERMANY 27 4.1 CURRENT ACCOUNT: SURPLUS FOR GERMANY, DEFICITS FOR PERIPHERY 27 4.2 FINANCIAL ACCOUNT: GERMAN FDI AND BANK LENDING TO THE PERIPHERY 28 5. -

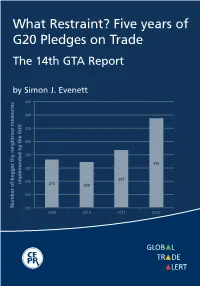

What Restraint? Five Years of G20 Pledges on Trade

What Restraint? Five Years of G20 Pledges on Trade What Restraint? Five Years For the past five years, leaders of the G20 countries have said they would not implement new trade restrictions, WTO-inconsistent export subsidies, What Restraint? Five years of or export taxes and quotas. They also promised to "roll back" any crisis-era protectionism that was imposed. Drawing upon nearly 3,800 separate reports of trade-related government measures collected and published by G20 Pledges on Trade the Global Trade Alert team, this Report contains the most up-to-date and comprehensive assessment of adherence to the G20's "standstill" on protectionism. At a time when the World Trade Organization is in the doldrums, the performance of this non-binding alternative to inter- The 14th GTA Report governmental cooperation on commercial policies takes on greater significance. This Report may be of interest to government officials, scholars, analysts, media experts, and students interested in how the governments of the by Simon J. Evenett world's largest economies have mixed trade liberalisation and beggar-thy- neighbour policies as the Great Recession has unfolded. The Report contains 360 six new measures of the resort to protectionism and the propensity to unwind it, computed and reported for each G20 member. Such measures, 340 which can be tracked over time, will add to the transparency of the world trading system. 320 300 280 335 260 287 240 implemented by the G20 273 269 220 Number of beggar thy neighbour measures 200 2009 2010 2011 2012 GLOB L TR DE -

C. Causes and Effects of Ptas

woRLD TRADE REPORT 2011 C. Causes and effects of PTAs: Is it all about preferences? A vast literature in economics and political science focuses on the causes and effects of preferential trade agreements – and in particular on the way that border measures, such as tariffs, impact trade flows among countries both inside and outside such agreements. Often referred to as the “standard analysis of preferential trade agreements”, this literature is discussed in detail in Sections C.1 and C.2. However, many recent regional agreements have moved beyond border measures to include deeper forms of rules and institutions that can only be partly understood by the standard analysis of preferential trade. An examination of the economic motives – and the key issues – that lie behind these deeper integration agreements is discussed in Section C.3. 92 II – The WTO AnD PReFeRential Trade Agreements pr C. o C A F e P uses F t e A R s en Contents : Is A n C I D es? t 1. Motives for PTAs 94 e all ff e 2. The standard economics of PTAs 100 ab C ts 3. Going beyond the standard analysis 109 out 4. Conclusions 114 Technical Appendix: Systemic effects of PTAs 118 Some key facts and findings • PTAs now cover a wider number of issues – beyond tariffs – and involve more structured institutional arrangements. • Global production networks increase the demand for deep agreements since they provide governance on a range of regulatory issues that are essential to the success of the networks. • Deep integration agreements can complement rather than substitute for the process of global integration. -

The Neoliberal Tide I: Summary

The Jus Semper Global Alliance Living Wages North and South The Neo-Capitalist Assault Essay Two of Part III (The Neo-Capitalist Assault) August 2001 GLOBAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT – A TLWNSI ISSUE ESSAY SERIES The Neoliberal Tide I: Summary The New Global Capitalist Market Democracy and its Corporate System and its Global Society Citizen Beggar-Thy-Neighbour Democracy By Alvaro J. de Regil a A Power no Longer Behind the Throne A Culture of Individualism From time to time TJSGA will issue essays on topics relevant to The Living Wages North and Global Oligopolisation to Increase South Initiative (TLWNSI). This paper is the Ninth Shareholder Value in the series “The Neo-Capitalist Assault” –a collection in development about Neoliberalism. No Pledge of Allegiance This is the first of two essays discussing the actual The New Map of the Neoliberal neo-capitalist assault in the last twenty years. Its Global System purpose is to explain how MNCs have overtaken democracy and dictate the policies of The Global Society governments for their benefit. The essay opens by asserting that the change of economic paradigm Inequality and Poverty in the U.S. was not intended to be a domestic policy but, rather, an instrument of foreign policy The Wonders of the New Economy to recover the U.S. imperial lustre and enable its corporations to increase and consolidate U.S. power into the new century. er behind the throne that could increase and consolidate the predominance of U.S. imperialism for the rest of the Twentieth Century With the change of economic paradigms during and into the Third Millennium. -

And Trade Policy

Volume 10 Number 1 2009/p. 1-11 esteyjournal.com The Estey Centre Journal of International Law and Trade Policy Recession, International Trade and the Fallacies of Composition William A. Kerr Senior Associate, The Estey Centre for Law and Economics in International Trade A truly global recession has not been manifest since the Great Depression of the 1930s. As a result, the multilateral institutions put in place at the end of the Second World War to ensure that a major depression never happened again have not been tested. One of the lessons of the Great Depression was that governments had a major role to play in managing the economy. The use of subsidies to affect economic outcomes was one manifestation of this expanded role. In a recession, sector specific subsidies will likely be requested by firms. Subsidies can distort trade, leading to the potential for beggar thy neighbour subsidy wars. Subsidies will be difficult to discipline in a global recession. Keywords: beggar thy neighbour, deficits, paradox of thrift, recession, subsidies Editorial Office: 410 22nd St. E., Suite 820, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, S7K 5T6. Phone (306) 244-4800; Fax (306) 244-7839; email: [email protected] 1 W. A. Kerr Fallacy of composition: a fallacy in which what is true in part is, on that account alone, alleged to be true of the whole. Paul Samuelson, Economics, 19661 During the 1928 election campaign, Republican presidential candidate Herbert Hoover pledged to help the beleaguered farmer by, among other things, raising tariff levels on agricultural products. But once the tariff schedule revision process got started, it proved impossible to stop.