Growing the Otome Game Market: Fan Labor and Otome Game Communities Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sisters Generation, and Fairy Fencer F Coming to Steam!

Immediate Release HYPERDIMENSION NEPTUNIA™ RE;BIRTH1, HYPERDIMENSION NEPTUNIA™ RE;BIRTH2: SISTERS GENERATION, AND FAIRY FENCER F COMING TO STEAM! LOS ANGELES, CA, December 24 – All aboard the Steam train! Idea Factory International is excited to announce that three titles – Hyperdimension Neptunia™ Re;Birth1 (PlayStation®Vita handheld system), Hyperdimension Neptunia™ Re;Birth2: Sisters Generation (PlayStation®Vita handheld system), and Fairy Fencer F (PlayStation®3 entertainment system) – will be available for download on Steam exclusively for the PC. Please stay tuned for details for each title’s release date and system requirements! Hyperdimension Neptunia Re;Birth1 Story In the world of Gamindustri, four goddesses known as CPUs battled for supremacy in the War of the Guardians. One of the CPUs - Neptune - was defeated by the others and banished from the heavens. In her fall from grace, her memories were lost but a mysterious book reveals itself to Neptune with knowledge of all of Gaminudstri's history. Joined by Compa, IF, and the sentient book known as Histoire, Neptune embarks on an extraordinary journey across four different nations on a quest to save the entire world! Hyperdimension Neptunia Re;Birth2: Sisters Generation Story 20XX - Gamindustri faces a dire crisis! Ever since the advent of ASIC - the Arfoire Syndicate of International Crime - morality has all but vanished. As much as 80 percent of all students are rumored to worship a being known as Arfoire, and the authorities have chosen to turn a blind eye to the threat. Basically, Gamindustri is pretty messed up, you guys. Ahem. Thus did Gamindustri fall into complete and utter disarray. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Boys' Love, Byte-Sized

School of Sociology and Social Policy Boys’ Love, Byte-sized: A Qualitative Exploration of Queer- themed Microfiction in Chinese Cyberspace Gareth Shaw B.A. (Hons), M.A. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2017 Acknowledgements I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Xiaoling Zhang, Professor Andrew Kam-Tuck Yip, and Dr Jeremy Taylor, for their constant support and faith in my research. This project would not have been possible without them. I also wish to convey my sincerest thanks to my examiners, Professor Sally Munt and Dr Sarah Dauncey, for their very insightful comments and suggestions, which have been invaluable to this project’s completion. I am grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council for funding this research (Award number: 1228555). I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to everyone who has participated in this project, particularly to the interview respondents, who gave so freely of their time. I am especially thankful to Huang Guan, Zhai Shunyi and Wei Ye for assisting me with some of the (often quite esoteric) Chinese to English translations. To my family, friends and colleagues, I thank you for being a constant source of comfort and advice when the light at the end of the tunnel seemed to have vanished. Special thanks go to Laura and Céline, for their support and encouragement during the long writing hours. Finally, to Juan and Mani, whose love and support means the world to me, I am eternally grateful to have had you both by my side on this journey. -

Appareil, 23 | 2021 Formes Programmées De L’Écriture Vidéoludique 2

Appareil 23 | 2021 Poïétique du jeu vidéo Formes programmées de l’écriture vidéoludique Hélène Sellier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/appareil/3853 DOI : 10.4000/appareil.3853 ISSN : 2101-0714 Éditeur MSH Paris Nord Référence électronique Hélène Sellier, « Formes programmées de l’écriture vidéoludique », Appareil [En ligne], 23 | 2021, mis en ligne le 31 mars 2021, consulté le 02 avril 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/appareil/3853 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/appareil.3853 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 2 avril 2021. Appareil est mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Formes programmées de l’écriture vidéoludique 1 Formes programmées de l’écriture vidéoludique Hélène Sellier NOTE DE L'AUTEUR Tout au long de cet article, je privilégie l’emploi de la forme féminine puisque l’utilisation du masculin n’est pas neutre au sein de la culture vidéoludique (sur ce point, il est possible de consulter l’ouvrage Genre et jeux vidéo dirigé par Fanny Lignon et publié en 2015 ou l’article de Torill Elvira Mortensen, « Anger, Fear, and Games: The Long Event of #GamerGate »). Utiliser « la joueuse » et « la créatrice » me permet de participer à rendre visible d’autres profils de joueurs ou joueuses. Ces expressions ont particulièrement leur place dans le cadre de cet article, dans la mesure où les communautés auxquelles je fais référence se construisent en marge des formes vidéoludiques qui prônent une « masculinité militarisée ». Introduction Cadre théorique : platform studies 1 Souvent envisagée à travers ses objets et les expériences qu’en font les joueurs, au sein des game studies et des play studies autant que dans le milieu de l’industrie, la culture vidéoludique est aussi une culture du logiciel. -

Folha De Rosto ICS.Cdr

“For when established identities become outworn or unfinished ones threaten to remain incomplete, special crises compel men to wage holy wars, by the cruellest means, against those who seem to question or threaten their unsafe ideological bases.” Erik Erikson (1956), “The Problem of Ego Identity”, p. 114 “In games it’s very difficult to portray complex human relationships. Likewise, in movies you often flit between action in various scenes. That’s very difficult to do in games, as you generally play a single character: if you switch, it breaks immersion. The fact that most games are first-person shooters today makes that clear. Stories in which the player doesn’t inhabit the main character are difficult for games to handle.” Hideo Kojima Simon Parkin (2014), “Hideo Kojima: ‘Metal Gear questions US dominance of the world”, The Guardian iii AGRADECIMENTOS Por começar quero desde já agradecer o constante e imprescindível apoio, compreensão, atenção e orientação dos Professores Jean Rabot e Clara Simães, sem os quais este trabalho não teria a fruição completa e correta. Um enorme obrigado pelos meses de trabalho, reuniões, telefonemas, emails, conversas e oportunidades. Quero agradecer o apoio de família e amigos, em especial, Tia Bela, João, Teté, Ângela, Verxka, Elma, Silvana, Noëmie, Kalashnikov, Madrinha, Gaivota, Chacal, Rita, Lina, Tri, Bia, Quelinha, Fi, TS, Cinco de Sete, Daniel, Catarina, Professor Albertino, Professora Marques e Professora Abranches, tanto pelas forças de apoio moral e psicológico, pelas recomendações e conselhos de vida, e principalmente pela amizade e memórias ao longo desta batalha. Por último, mas não menos importante, quero agradecer a incessante confiança, companhia e aceitação do bom e do mau pela minha Twin, Safira, que nunca me abandonou em todo o processo desta investigação, do meu caminho académico e da conquista da vida e sonhos. -

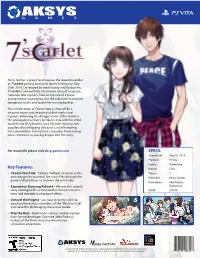

SPECS: Key Features

Aksys Games is proud to announce the moonlit wonder of 7’scarlet coming to mystify North America on May 25th, 2018. Developed by Idea Factory and Toybox Inc, 7’scarlet is a beautifully interwoven story of suspense, romance, and mystery. Take on the role of a brave young woman journeying into the unknown to uncover dangerous truths and locate her missing brother. The remote town of Okune-zato is shaped like a crescent moon and shrouded in dark myths and legends. Following the disappearance of her brother, the protagonist ventures to Okune-zato with her child- hood friend. They nd the area rife with mystery and populated by intriguing characters, each harboring their own hidden motivations. Encounter heart-racing twists and turns as you dig deeper into the story. For more info please visit aksysgames.com SPECS: Street Date: May 25, 2018 Platform: PS Vita Genre: Adventure Key Features: Rating: Teen • Choose Your Fate - Explore multiple character paths Players: 1 and change the course of the story! Play through the Publisher: Aksys Games game multiple times to uncover the entire tale. Developers: Idea Factory • Experience Stunning Artwork - Witness this colorful Toybox Inc. story coming to life with beautiful character illustra- MSRP: $39.99 tions and dynamic background eects. • Unravel the Enigma - Use your detective skills to question the eclectic members of the “Mystery Club” and solve this challenging interactive puzzle. • Play the Best - Experience a crime-solving mystery from famed developer Otomate (Idea Factory), makers of the nest visual novel/romance simulation adventures. ©2018 IDEA FACTORY/TOYBOX Inc. All rights reserved. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Dansō, Gender, and Emotion Work in a Tokyo Escort Service

WALK LIKE A MAN, TALK LIKE A MAN: DANSŌ, GENDER, AND EMOTION WORK IN A TOKYO ESCORT SERVICE A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 MARTA FANASCA SCHOOL OF ARTS, LANGUAGES AND CULTURES Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables ...................................................................................................... 5 Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 6 Declaration and Copyright Statement .................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................. 8 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 Significance and aims of the research .................................................................................. 12 Outline of the thesis ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1 Theoretical Framework and Literature Review Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 16 1.1 Masculinity in Japan ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2 Dansō and gender definition -

Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. Introduces Playstation®4 (Ps4™)

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SONY COMPUTER ENTERTAINMENT INC. INTRODUCES PLAYSTATION®4 (PS4™) PS4’s Powerful System Architecture, Social Integration and Intelligent Personalization, Combined with PlayStation Network with Cloud Technology, Delivers Breakthrough Gaming Experiences and Completely New Ways to Play New York City, New York, February 20, 2013 –Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) today introduced PlayStation®4 (PS4™), its next generation computer entertainment system that redefines rich and immersive gameplay with powerful graphics and speed, intelligent personalization, deeply integrated social capabilities, and innovative second-screen features. Combined with PlayStation®Network with cloud technology, PS4 offers an expansive gaming ecosystem that is centered on gamers, enabling them to play when, where and how they want. PS4 will be available this holiday season. Gamer Focused, Developer Inspired PS4 was designed from the ground up to ensure that the very best games and the most immersive experiences reach PlayStation gamers. PS4 accomplishes this by enabling the greatest game developers in the world to unlock their creativity and push the boundaries of play through a system that is tuned specifically to their needs. PS4 also fluidly connects players to the larger world of experiences offered by PlayStation, across the console and mobile spaces, and PlayStation® Network (PSN). The PS4 system architecture is distinguished by its high performance and ease of development. PS4 is centered around a powerful custom chip that contains eight x86-64 cores and a state of the art graphics processor. The Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) has been enhanced in a number of ways, principally to allow for easier use of the GPU for general purpose computing (GPGPU) such as physics simulation. -

LNCS 8018, Pp

The Study to Clarify the Type of “Otome-Game” User Misaki Tanikawa and Yumi Asahi Department of Systems Engineering, Shizuoka University 3-5-1 Johoku Naka-ku Hamamatsu 432-8561, Japan [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. The authors use the Marketing Science.And the one of the authors study to clarify the type of “Otome-game”user. “Otome-game” users have many kinds of liking or desire.So it is difficult for makers to create products that match with the demands of users.By this research, users and makers will be able to trade at the suitable type of demands. So the auther will research the market of the “Otome-game”. The data that is collected by marketing research is analyzed by SPSS. Keywords: Marketing Science, Otome-game, Japanese culture, User Analy- sis,SPSS. 1 Introduction I research to clarify the types of “Otome game” users, using marketing science. 1.1 What Is Otome Game? “Otome game” means love simulation game for women in Japanese. The word “Otome ” means a young girl, and this word also suggests a virgin indirectly. Fig. 1. Explanation of Otome game Otome game is a game genre like novel. Each one has own story. The player of the game handles a girl who is the heroine of the story. The player can change heroine's name. Of course, the player can change it into her name.And the heroine meets hand- some men of various characters in the game. She fall in love with one of them. As a result, the player who handles the heroine can enjoy virtual love with the man in the game. -

Towards Accessibility of Games: Mechanical Experience, Competence Profiles and Jutsus

Towards Accessibility of Games: Mechanical Experience, Competence Profiles and Jutsus. Abstract Accessibility of games is a multi-faceted problem, one of which is providing mechanically achievable gameplay to players. Previous work focused on adapting games to the individual through either dynamic difficulty adjustment or providing difficulty modes; thus focusing on their failure to meet a designed task. Instead, we look at it as a design issue; designers need to analyse the challenges they craft to understand why gameplay may be inaccessible to certain audiences. The issue is difficult to even discuss properly, whether by designers, academics or critics, as there is currently no comprehensive framework for that. That is our first contribution. We also propose challenge jutsus – structured representations of challenge descriptions (via competency profiles) and player models. This is a first step towards accessibility issues by better understanding the mechanical profile of various game challenges and what is the source of difficulty for different demographics of players. 1.0 Introduction Different Types of Experience When discussing, critiquing, and designing games, we are often concerned with the “player experience” – but what this means is unsettled as games are meant to be consumed and enjoyed in various ways. Players can experience games mechanically (through gameplay actions), aesthetically (through the visual and audio design), emotionally (through the narrative and characters), socially (through the communities of players), and culturally (through a combination of cultural interpretations and interactions). Each aspect corresponds to different ways that the player engages with the game. We can map the different forms of experience to the Eight Types of Fun (Hunicke, LeBlanc, & Zubek, 2004) (Table 1).