2А–Аwho Claims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston

The Tarring and Feathering of Thomas Paul Smith: Common Schools, Revolutionary Memory, and the Crisis of Black Citizenship in Antebellum Boston hilary j. moss N 7 May 1851, Thomas Paul Smith, a twenty-four-year- O old black Bostonian, closed the door of his used clothing shop and set out for home. His journey took him from the city’s center to its westerly edge, where tightly packed tene- ments pressed against the banks of the Charles River. As Smith strolled along Second Street, “some half-dozen” men grabbed, bound, and gagged him before he could cry out. They “beat and bruised” him and covered his mouth with a “plaster made of tar and other substances.” Before night’s end, Smith would be bat- tered so severely that, according to one witness, his antagonists must have wanted to kill him. Smith apparently reached the same conclusion. As the hands of the clock neared midnight, he broke free of his captors and sprinted down Second Street shouting “murder!”1 The author appreciates the generous insights of Jacqueline Jones, Jane Kamensky, James Brewer Stewart, Benjamin Irvin, Jeffrey Ferguson, David Wills, Jack Dougherty, Elizabeth Bouvier, J. M. Opal, Lindsay Silver, Emily Straus, Mitch Kachun, Robert Gross, Shane White, her colleagues in the departments of History and Black Studies at Amherst College, and the anonymous reviewers and editors of the NEQ. She is also grateful to Amherst College, Brandeis University, the Spencer Foundation, and the Rose and Irving Crown Family for financial support. 1Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Julian McCrea, Benjamin F. Roberts, and William J. -

Chapter I: the Supremacy of Equal Rights

DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 CHAPTER I: THE SUPREMACY OF EQUAL RIGHTS J. Morgan Kousser SOCIAL SCIENCE WORKING PAPER 620 March 1987 ABSTRACT The black and white abolitionist agitation of the school integ ration issue in Massachusetts from 1840 to 1855 gave us the fi rst school integ ration case filed in Ame rica, the fi rst state sup reme cou rt decision re po rted on the issue, and the fi rst state-wide law banning ra cial disc rimination in admission to educational institutions. Wh o favo red and who opposed school integ ration, and what arguments did each side make? We re the types of arguments that they offe re d diffe rent in diffe re nt fo ru ms? We re they diffe rent from 20th centu ry arguments? Wh y did the movement triumph, and why did it take so long to do so? Wh at light does the st ruggle th row on views on ra ce re lations held by membe rs of the antebellum black and white communities, on the cha racte r of the abolitionist movement, and on the development of legal doct rines about ra cial equality? Pe rhaps mo re gene rally, how should histo ri ans go about assessing the weight of diffe rent re asons that policymake rs adduced fo r thei r actions, and how flawed is a legal histo ry that confines itself to st rictly legal mate ri als? How can social scientific theo ry and statistical techniques be profitably applied to politico-legal histo ry? Pa rt of a la rge r project on the histo ry of cou rt cases and state and local provisions on ra cial disc rimination in schools, this pape r int roduces many of the main themes, issues, and methods to be employed in the re st of the book. -

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution

Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Abraham Lincoln, Kentucky African Americans and the Constitution Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Collection of Essays Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council © Essays compiled by Alicestyne Turley, Director Underground Railroad Research Institute University of Louisville, Department of Pan African Studies for the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission, Frankfort, KY February 2010 Series Sponsors: Kentucky African American Heritage Commission Kentucky Historical Society Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission Kentucky Heritage Council Underground Railroad Research Institute Kentucky State Parks Centre College Georgetown College Lincoln Memorial University University of Louisville Department of Pan African Studies Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Kentucky Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission (KALBC) was established by executive order in 2004 to organize and coordinate the state's commemorative activities in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the birth of President Abraham Lincoln. Its mission is to ensure that Lincoln's Kentucky story is an essential part of the national celebration, emphasizing Kentucky's contribution to his thoughts and ideals. The Commission also serves as coordinator of statewide efforts to convey Lincoln's Kentucky story and his legacy of freedom, democracy, and equal opportunity for all. Kentucky African American Heritage Commission [Enabling legislation KRS. 171.800] It is the mission of the Kentucky African American Heritage Commission to identify and promote awareness of significant African American history and influence upon the history and culture of Kentucky and to support and encourage the preservation of Kentucky African American heritage and historic sites. -

LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

1 LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ewis Hayden died in Boston on Sunday morning April 7, 1889. L His passing was front- page news in the New York Times as well as in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald and Boston Evening Transcript. Leading nineteenth century reformers attended the funeral including Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights champion Lucy Stone. The Governor of Massachusetts, Mayor of Boston, and Secretary of the Commonwealth felt it important to participate. Hayden’s was a life of real signi cance — but few people know of him today. A historical marker at his Beacon Hill home tells part of the story: “A Meeting Place of Abolitionists and a Station on the Underground Railroad.” Hayden is often described as a “man of action.” An escaped slave, he stood at the center of a struggle for dignity and equal rights in nine- Celebrate teenth century Boston. His story remains an inspiration to those who Black Historytake the time to learn about Month it. Please join the Town of Framingham for a special exhibtion and visit the Framingham Public Library for events as well as displays of books and resources celebrating the history and accomplishments of African Americans. LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Presented by the Commonwealth Museum A Division of William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Opens Friday February 10 Nevins Hall, Framingham Town Hall Guided Tour by Commonwealth Museum Director and Curator Stephen Kenney Tuesday February 21, 12:00 pm This traveling exhibit, on loan from the Commonwealth Museum will be on display through the month of February. -

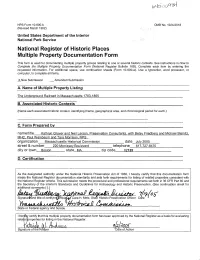

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPSForm10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) . ^ ;- j> United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. _X_New Submission _ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________ The Underground Railroad in Massachusetts 1783-1865______________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) C. Form Prepared by_________________________________________ name/title Kathrvn Grover and Neil Larson. Preservation Consultants, with Betsy Friedberg and Michael Steinitz. MHC. Paul Weinbaum and Tara Morrison. NFS organization Massachusetts Historical Commission________ date July 2005 street & number 220 Morhssey Boulevard________ telephone 617-727-8470_____________ city or town Boston____ state MA______ zip code 02125___________________________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National -

Courthouse-Narrative.Pdf

Second Leesburg Courthouse, 1815 REPORT OF THE LOUDOUN COUNTY HERITAGE COMMISSION THE HISTORY OF THE COUNTY COURTHOUSE AND ITS ROLE IN THE PATH TO FREEDOM, JUSTICE AND RACIAL EQUALITY IN LOUDOUN COUNTY March 1, 2019 Robert A. Pollard, Editor This report is not intended to be a complete history of the Loudoun County Courthouse, but contains a series of vignettes, representations of specific events and people, selected statistics, reprints of published articles, original articles by Commissioners, copies of historic documents and other materials that help illustrate its role in the almost three century struggle to find justice for all people in Loudoun County. Attachment 2 Page 2 MEMBERS OF HERITAGE COMMISSION COURTHOUSE SUBCOMMITTEE Co-Chairs – Donna Bohanon, Robert A. Pollard Members –Mitch Diamond, Lori Kimball, Bronwen Souders, Michelle Thomas, William E. Wilkin, Kacey Young. Staff – Heidi Siebentritt, John Merrithew TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue -- p. 3 Overview Time Line of Events in Loudoun County History -- pp. 4-8 Brief History of the Courthouse and the Confederate Monument -- pp. 9-12 I: The Period of Enslavement Enslavement, Freedom and the Courthouse 1757-1861 -- pp. 13-20 Law and Order in Colonial Loudoun (1768) -- pp. 21-23 Loudoun and the Revolution, 1774-1776 -- pp. 24-25 Ludwell Lee, Margaret Mercer and the Auxiliary Colonization Society of Loudoun County -- pp. 27-28 Loudoun, Slavery and Three Brave Men (1828) -- pp. 29-31 Joseph Trammell’s Tin Box -- p. 32 Petition from Loudoun County Court to expel “Free Negroes” to Africa (1836) -- pp. 33-35 The Leonard Grimes Trial (1840) -- pp. 36-37 Trial for Wife Stealing (1846) -- pp. -

The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 6-21-2018 The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Mary Sarah Bilder Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Profession Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Laurel Davis and Mary Sarah Bilder. "The Library of Robert Morris, Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist." (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Library of Robert Morris, Antebellum Civil Rights Lawyer & Activist∗ Laurel Davis** and Mary Sarah Bilder*** Contact information: Boston College Law Library Attn: Laurel Davis 885 Centre St. Newton, MA 02459 Abstract (50 words or less): This article analyzes the Robert Morris library, the only known extant, antebellum African American-owned library. The seventy-five titles, including two unique pamphlet compilations, reveal Morris’s intellectual commitment to full citizenship, equality, and participation for people of color. The library also demonstrates the importance of book and pamphlet publication as means of community building among antebellum civil rights activists. -

The Long American Revolution: Black Abolitionists and Their

Gordon S. Barker. Fugitive Slaves and the Unfinished American Revolution: Eight Cases, 1848-1856. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2013. 232 pp. $45.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-7864-6987-1. Reviewed by Emily Margolis Published on H-Law (January, 2014) Commissioned by Craig Scott U.S. historians tend to mark the end of the their Revolution was the war against slavery and American Revolution as George Bancroft did, in their quest was to create a “more perfect union.” the early 1780s when military action with the Therefore, he claims their Revolution ended--at British ceased (upon either the surrender of Corn‐ the very earliest date--with the ratification of the wallis at Yorktown in 1781 or the Treaty of Paris Thirteenth Amendment. in 1783). As Gordon Barker rightly points out, in Using black and white abolitionist lectures, the 1980s, American and Atlantic social historians correspondence, annual reports, newspapers, di‐ began to produce a new body of scholarship that aries, and memoirs, as well as Northern and challenged this periodization as they found ordi‐ Southern newspapers, fugitive slave trials, and nary men, women, and African Americans em‐ lawyers’ papers, Barker employs a sociopolitical ploying the principles of the Declaration of Inde‐ approach to illustrate African Americans’ contin‐ pendence in their battle to gain freedom from dif‐ ued battle against the tyranny of slavery. To show ferent types of tyranny long after the end of the their continued Revolution, he centers his book eighteenth century. In fact, some argue that the on the late 1840s and 1850s and chronicles eight battle, for these groups, continues today. -

Black Abolitionists Used the Terms “African,” “Colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F

$2 SUGGESTED DONATION The initiative of black presented to the provincial legislature by enslaved WHAT’S IN A NAME? Black people transformed a war men across greater Boston. Finally, in the early 1780s, Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman (Image 1) to restore the Union into of Sheffield and Quock Walker of Framingham Throughout American history, people Abolitionists a movement for liberty prevailed in court. Although a handful of people of African descent have demanded and citizenship for all. of color in the Bay State still remained in bondage, the right to define their racial identity (1700s–1800s) slavery was on its way to extinction. Massachusetts through terms that reflect their In May 1861, three enslaved black men sought reported no slaves in the first census in 1790. proud and complex history. African refuge at Union-controlled Fort Monroe, Virginia. Americans across greater Boston Rather than return the fugitives to the enemy, Throughout the early Republic, black abolitionists used the terms “African,” “colored,” Commanding Officer Benjamin F. Butler claimed pushed the limits of white antislavery activists and “negro” to define themselves the men as “contrabands of war” and put them to who advocated the colonization of people of color. before emancipation, while African work as scouts and laborers. Soon hundreds of In 1816, a group of whites organized the American Americans in the early 1900s used black men, women, and children were streaming Colonization Society (ACS) for the purpose of into the Union stronghold. Congress authorized emancipating slaves and resettling freedmen and the terms “black,” “colored,” “negro,” the confiscation of Confederate property, freedwomen in a white-run colony in West Africa. -

Wendell Phillips Wendell Phillips

“THE CHINAMAN WORKS CHEAP BECAUSE HE IS A BARBARIAN AND SEEKS GRATIFICATION OF ONLY THE LOWEST, THE MOST INEVITABLE WANTS.”1 For the white abolitionists, this was a class struggle rather than a race struggle. It would be quite mistaken for us to infer, now that the civil war is over and the political landscape has 1. Here is what was said of the Phillips family in Nathaniel Morton’s NEW ENGLAND’S MEMORIAL (and this was while that illustrious family was still FOB!): HDT WHAT? INDEX WENDELL PHILLIPS WENDELL PHILLIPS shifted, that the stereotypical antebellum white abolitionist in general had any great love for the welfare of black Americans. White abolitionist leaders knew very well what was the source of their support, in class conflict, and hence Wendell Phillips warned of the political danger from a successful alliance between the “slaveocracy” of the South and the Cotton Whigs of the North, an alliance which he termed “the Lords of the Lash and the Lords of the Loom.” The statement used as the title for this file, above, was attributed to Phillips by the news cartoonist and reformer Thomas Nast, in a cartoon of Columbia facing off a mob of “pure white” Americans armed with pistols, rocks, and sticks, on behalf of an immigrant with a pigtail, that was published in Harper’s Weekly on February 18, 1871. There is no reason to suppose that the cartoonist Nast was failing here to reflect accurately the attitudes of this Boston Brahman — as we are well aware how intensely uncomfortable this man was around any person of color. -

William Leonard, “'Black and Irish Relations in 19Th Century Boston

William Leonard, “’Black and irish Relations in 19th Century Boston: The Interesting Case Lawyer Robert Morris” Historical Journal of Massachusetts Volume 37, No. 1 (Spring 2009). Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/ number/ date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/mhj. Robert Morris (1823-82) was the second African Amer- ican to pass the bar exam in the United States. An ardent abolitionist, during the 1840s he was the only practicing black lawyer in Boston. In 1849 he represented Ben- jamin Roberts, whose daughter had been denied entry to the white public schools. Charles Sumner eventu- ally argued this case before the Massachusetts Supreme Court. During the 1850s Morris participated in three daring rescues of fugitive slaves who were being held in custody for return to the South. After the Civil War he converted to Catholicism, which was then dominated by the Irish. Both before and after the war a majority of Morris’ clients were Irish. (Photo courtesy of the Social Law Library, Boston) Black and Irish Relations in Nineteenth Century Boston: The Interesting Case of Lawyer Robert Morris WILLIAM LEONARD Abstract: This article examines the life of Robert Morris (1823-82), Boston’s first African American lawyer and a noted abolitionist. -

Early Newspaper Accounts of Prince Hall Freemasonry

Early Newspaper Accounts of Prince Hall Freemasonry S. Brent Morris, 33°, g\c\, & Paul Rich, 32° Fellow & Mackey Scholar Fellow OPEN TERRITORY n 1871, an exasperated Lewis Hayden1 wrote to J. G. Findel2 about the uncertain and complicated origins of grand lodges in the United States and the inconsistent attitudes displayed towards the char- I tering in Boston of African Lodge No. 459 by the Grand Lodge of Eng- land: “The territory was open territory. The idea of exclusive State jurisdiction by Grand Lodges had not then been as much as dreamed of.” 3 The general 1. Hayden was a former slave who was elected to the Massachusetts legislature and raised money to finance John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. His early life is described by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her book, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Jewett, Proctor & Worthington, 1853). 2. Findel was a member of Lodge Eleusis zur Verschwiegenheit at Baireuth in 1856 and edi- tor of the Bauhütte as well as a founder of the Verein Deutscher Freimaurer (Union of Ger- man Freemasons) and author in 1874 of Geist unit Form der Freimaurerei (Genius and Form of Freemasonry). 3. Lewis Hayden, Masonry Among Colored Men in Massachusetts (Boston: Lewis Hayden, 1871), 41. Volume 22, 2014 1 S. Brent Morris & Paul Rich theme of Hayden’s correspondence with Findel was that African-American lodges certainly had at least as much—and possibly more—claim to legiti- mate Masonic origins as the white lodges did, and they had been denied rec- ognition because of racism.4 The origins of African-American Freemasonry in the United States have generated a large literature and much dispute.