Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional News

REGIONAL FIS E IES NEWS J liaRY 1970 ( 1 • Mdeit,k40 111.111111111...leit 9 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA NEWFOUNDLAND REGION REDUCTION PLANT OFFICIALLY OPENED The ne3 3/4-million NATLAKE herring reduction plant at Burgeo was officially opened January 28th by Premier J. R. Smallwood. Among special guests attending the opening ceremonies were: federal Transport Minister Don Jamieson, provincial Minister of Fisheries A. Maloney and our Regional Director, H. R. Bradley. Privately financed, the new plant is a joint effort of Spencer Lake, the Clyde Lake Group and National Sea Products of Nova Scotia. Ten herring seiners from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and British Columbia are under contract to land catches at the plant. Fifty people will be employed as production workers at the plant which will operate on a 21-hour, three shift basis. - 0 - 0 - 0 - ATTEND CAMFI CONFERENCE Four representatives of Regional Headquarters staff are attending the Conference on Automation and Mechanization in the Fishing Industry being held in Montreal February 3 - 6. The conference is sponsored by the Federal-Provincial Atlantic Fisheries Committee which is comprised of the deputy ministers responsible for fisheries in the Federal Government and the governments of Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The Secretariat for the conference was provided by the Industrial Development Service, Department of Fisheries and Forestry, Ottawa. Attending the conference from the Newfoundland. Region were: J. P. Hennessey, R. n. Prince, m. Barnes and E. B. Dunne. ****** ****** FROZEN TROUT RETURN TO LIFE A true story told by Bob Ebsary, a former technician with our Inspection Laboratory, makes one wonder whether or not trout, like cats, have nine lives. -

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload

ROUTING GUIDE - Less Than Truckload Updated December 17, 2019 Serviced Out Of City Prov Routing City Carrier Name ABRAHAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADAMS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADEYTON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS BEACH NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ADMIRALS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ALLANS ISLAND NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AMHERST COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANCHOR POINT NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ANGELS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point APPLETON NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AQUAFORTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARGENTIA NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ARNOLDS COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEN COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point ASPEY BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point AVONDALE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACK HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BACON COVE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGER NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BADGERS QUAY NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAIE VERTE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAINE HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAKERS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARACHOIS BROOK NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARENEED NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARR'D ISLANDS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BARTLETTS HARBOUR NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAULINE EAST NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY BULLS NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY DE VERDE NL TORONTO, ON Interline Point BAY L'ARGENT NL TORONTO, ON -

Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 Dean, Jerry, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $19,200.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $19,200.00 Funds Available (Net of HST): $0.00 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 100.0% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 01-Apr-18 HOA004815 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-May-18 HOA004871 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Jun-18 HOA004908 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Jul-18 HOA004946 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Aug-18 HOA004983 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Sep-18 HOA005021 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. -

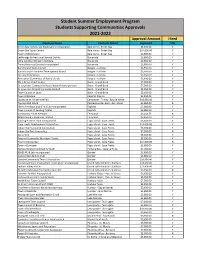

Students Supporting Communities Program

Student Summer Employment Program Students Supporting Communities Approvals 2021-2022 Approval Amount Hired Employer Name Electoral District Approved Y/N Green Bay Community Employment Corporation Baie Verte - Green Bay $3,650.00 Y Green Bay Youth Centre Baie Verte - Green Bay $14,600.00 Y Town of Woodstock Baie Verte - Green Bay $3,650.00 Y Lethbridge & Area Local Service District Bonavista $3,650.00 Y Little Catalina Women's Institute Bonavista $3,650.00 Y Trinity Historical Society Incorporated Bonavista $3,650.00 Y Burnt Island Town council Burgeo - La Poile $3,550.00 Y Burnt Islands Economic Development Board Burgeo - La Poile $3,500.00 Y DG Four Enterprises Burgeo - La Poile $3,650.00 Y Recreation Committee of Burnt Islands Burgeo - La Poile $3,650.00 Y Main Street Youth Centre Burin - Grand Bank $7,300.00 Y St. Lawrence Community Youth Network Incorporated Burin - Grand Bank $7,300.00 Y St. Lawrence Retirement Living Limited Burin - Grand Bank $3,650.00 Y Town Council of Lawn Burin - Grand Bank $3,650.00 Y Town of Bauline Cape St. Francis $3,550.00 Y Society of St. Vincent de Paul Carbonear - Trinity - Bay de Verde $10,950.00 Y Tourism Bell Island Conception Bay East - Bell Island $3,650.00 N Norris Arm Boys and Girls Club Incorporated Exploits $7,300.00 Y Town Council of Leading Tickles Exploits $3,650.00 Y Community Youth Network Ferryland $3,218.75 N MMB Dining Enterprises Limited Ferryland $3,650.00 Y Banting Historic Trust Incorporated Fogo Island - Cape Freels $3,650.00 Y Cape Freels Development Association Fogo Island - -

BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 P.M. December 7, 2017 Attendance

Central Newfoundland Waste Management P. O. Box 254, Norris Arm, NL, A0G 3M0 Phone: 709 653 2900 Fax :709 653 2920 Web: www.cnwmc.com E-mail: [email protected] BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 p.m. December 7, 2017 Attendance Terry Best Badger/Buchans/Buchans Junction/Millertown – Ward 1 Kevin Butt NWI/Twillingate – Ward 3 Wayne Collins Fogo Island – Ward 4 Keith Howell Gander Bay – Ward 5 Lloyd Pickett Indian Bay – Ward 6 Glenn Arnold Terra Nova – Ward 7 Percy Farwell Town of Gander - Ward 8 Darrin Finn Town of Grand Falls-Windsor – Ward 9 Ross Rowsell Norris Arm/Norris Arm North – Ward 11 Derrick Luff Direct Haul – Ward 12 Ed Evans Chief Administrative Officer - CNWM Karen White Attwood Manager of Finance/Administration – CNWM Mark Attwood Manager of Operations – CNWM Jerry Collins Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment - Conference Call Ian Duffett Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment – Conference Call Apologies Brad Hefford Service NL Wayne Lynch Service NL Robert Elliott Point Leamington – Ward 2 Perry Pond Bishops Falls/Botwood/Lewisporte – Ward 10 1. Review of Minutes of November 9, 2017 MOTION: Moved by G. Arnold to adopt the minutes of November 9, 2017. Seconded by R. Rowsell. M/C 2. Business Arising Mayor Betty Clarke has stepped down as representative of Ward 10 (Botwood, Bishops Falls, and Lewisporte). Perry Pond will now represent Ward 10. 3. Technical Committee – Representatives from the Board, Government and engineers from the Towns of Grand Falls – Windsor and Gander will continue to sit at the Technical committee December 7, 2017 4. Financial Report MOTION: Moved by W. -

HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland

55°15' 55°0' 54°45' 54°30' 54°15' 54°0' 53°45' 53°30' 53°15' 50°15' Department of Environment and Conservation Department of Natural Resources Map No. 3b HYDROGEOLOGY 50°0' Central Newfoundland Well Yield Well Depth 50°0' Characteristics Characteristics (m) Number (L/min) Hydrostratigraphic Unit Lithology of Wells Average Median Average Median Unit 1 schist, gneiss, Low to Moderate Yield 73 20 6 51 48 quartzite, slate Metamorphic Strata siltstone, Unit 2 conglomerate, argillite, Low to Moderate Yield 1403 20 7 51 46 greywacke, with Sedimentary Strata minor volcanic 49°45' flows and tuff Unit 3 basic pillow Low to Moderate Yield lava, flows, 723 22 9 50 46 Barr'D Islands Volcanic Strata breccia and tuff 49°45' Fogo Joe Batt's Arm Tilting Unit 4 mafic and ultramafic Shoal Bay Pike's Arm Low Yield intrusions of ophiolite 13 9 7 58 61 Herring Neck Change Islands complexes FogoC oIsolkasn Pdond Ophiolite Complexes Durrell Deep Bay Fogo Island Region Unit 5 granite, granodiorite, Salt Harbour N o r t h Twillingate Island Harbour diabase, and diorite 688 22 9 44 37 Little Harbour Cobbs Arm A t l a n t i c Low to Moderate Yield Too Good Arm Seldom intrusions Notre Dame Bay O c e a n Plutonic Strata Gilliards Cove F Jenkins Cove rid Keattyle Cove Black Duck Cove Little Seldom Tizzard's Harbour B Rogers Cove ay Indian Cove Surficial deposits - Unconsolidated sediments Stag Harbour Newville Valley Pond Moreton's Harbour Surficial Hydrostratigraphic Units Fairbanks-Hillgrade Unit A - Till Deposits Hillgrade Port Albert Well yields range from 2 litres per minute (L/min) to 136 L/min and averaged 29 L/min Bridgeport 49°30' Virgin Arm-Carter's Cove with a median value of 18 L/min. -

The Communications and Electronics Branch

THE ORDRES PERMANENTS COMMUNICATIONS AND DE LA BRANCHE DES ELECTRONICS COMMUNICATIONS BRANCH ET DE STANDING ORDERS L’ÉLECTRONIQUE Recommendation for amendments should be Les recommandations de modifications devront forwarded to the Communications and être envoyées à l’adjudant-chef de la Branche Electronics Branch Chief Warrant Officer. des communications et de l’électronique. These Standing Orders have been amended at the Les présents Ordres permanents ont été modifiés NCMs Advisory council meeting on 11 May 2004. lors de la réunion du Conseil consultatif des MR le 11 mai 2004. i GLOSSARY OF TERMS GLOSSAIRE ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE DES MATIÈRES Article CHAPTER 1 - ORGANIZATION CHAPITRE 1 - ORGANISATION 1.01 Formation 1.01 Constitution 1.02 Role 1.02 Rôle 1.03 Former Services 1.03 Les anciens services 1.04 Communication Reserves 1.04 La Réserve des communications 1.05 Branch Title 1.05 Appellation de la Branche 1.06 The C&E Association 1.06 L’Association des C et E 1.07 Precedence 1.07 Priorité CHAPTER 2 - BRANCH CHAPITRE 2 - TITRES ET APPOINTMENTS AND COMITÉS AU SEIN DE LA COMMITTEES BRANCHE 2.01 The Colonel-in-Chief 2.01 Colonel en chef 2.04 Colonel Commandant 2.04 Colonel commandant 2.06 Branch Adviser and Leader 2.06 Conseiller et chef de la Branche 2.09 The Communications & Electronic 2.09 L’association des Communications Association et de l’Électronique 2.22 Business plan and the C & E 2.22 Plan d’activités et Fonds du Musée et de Museum/Branch fund la Branche des C et E 2.23 Resources 2.23 Ressources Annex A - Colonels Commandant -

BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 P.M. May 16, 2019 Attendance

Central Newfoundland Waste Management P. O. Box 254, Norris Arm, NL, A0G 3M0 Phone: 709 653 2900 Fax :709 653 2920 Web: www.cnwmc.com E-mail: [email protected] BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 p.m. May 16, 2019 Attendance Robert Elliott Point Leamington – Ward 2 – Chair Kevin Butt NWI/Twillingate – Ward 3 Wayne Collins Fogo Island – Ward 4 Lloyd Pickett Indian Bay – Ward 6 Glenn Arnold Terra Nova – Ward 7 – Vice Chair Percy Farwell Town of Gander - Ward 8 – Secretary Ross Rowsell Norris Arm/Norris Arm North – Ward 11 – Conference Call Derrick Luff Direct Haul – Ward 12 - Treasurer Ed Evans Chief Administrative Officer – CNWM Karen White Attwood Manager of Finance/Administration – CNWM Mark Attwood Manager of Operations – CNWM Richard Power Auditor Apologies Gary Noftle Buchan’s Junction – Ward 1 Darrin Finn Town of Grand Falls-Windsor – Ward 9 Perry Pond Bishops Falls/Botwood/Lewisporte – Ward 10 Keith Howell Gander Bay – Ward 5 Brad Hefford Service NL Wayne Lynch Service NL Jerry Collins Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment 1. Presentation of the 2018 Audited Financial Statements by Richard Power – Auditor MOTION: Moved by P. Farwell to adopt the 2018 audited financial statements, as presented with identified correction. Second by K. Butt. M.C. 2. Review of Minutes of March 21, 2019 and April 11, 2019 MOTION: Moved by W. Collins to adopt the minutes of March 21, 2019. Second by G. Arnold. M.C. MOTION: Moved by L. Pickett to adopt the minutes of April 11, 2019 – Special Meeting. Second by D. Luff. M.C. May 16, 2019 3. -

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: a Bibliography and Documentary Resource List

The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line: A Bibliography and Documentary Resource List Prepared for the Arctic Institute of North America By: P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Ph.D. Matthew J. Farish, Ph.D. Jennifer Arthur-Lackenbauer, M.Sc. October 2005 © 2005 The Arctic Institute of North America ISBN 1-894788-01-X The DEW Line: Bibliography and Documentary Resource List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PREFACE 2 2.0 BACKGROUND DOCUMENTS 3 2.1 Exchange of Notes (May 5, 1955) Between Canada and the United States Of America Governing the Establishment of a Distant Early Warning System in Canadian Territory.......................................................................................................... 3 2.2 The DEW Line Story in Brief (Western Electric Corporation, c.1960) ……………… 9 2.3 List of DEW Line Sites ……………………………………….…………………….... 16 3.0 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS 23 3.1 Rt. Hon. John George Diefenbaker Centre ……………………………………….…... 23 3.2 Library and Archives Canada …………………………………….…………………... 26 3.3 Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage ………………. 46 3.4 NWT Archives Council, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre ……………….... 63 3.5 Yukon Territorial Archives, Whitehorse, YT ………………………………………… 79 3.6 Hudson Bay Company Archives ……………………………………………………... 88 3.7 Archives in the United States ……………………………………………………….… 89 4.0 PUBLISHED SOURCES 90 4.1 The Globe and Mail …………………………………………………………………………… 90 4.2 The Financial Post ………………………………………………………………………….…. 99 4.3 Other Print Media …………………………………………………………………..… 99 4.4 Contemporary Journal Articles ……………………………………………………..… 100 4.5 Government Publications …………………………………………………………….. 101 4.6 Corporate Histories ………………………………………………………………...... 103 4.7 Professional Journal Articles ………………………………………………………..… 104 4.8 Books ………………………………………………………………………………..… 106 4.9 Scholarly and Popular Articles ………………………………………………….……. 113 4.10 Environmental Issues and Cleanup: Technical Reports and Articles …………….…. 117 5.0 OTHER SOURCES 120 5.1 Theses and Dissertations ……………………………………………………………... -

Minutes Public Meeting Central Newfoundland

MINUTES PUBLIC MEETING CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT June 17, 2003 at 7:00 p.m. Norris Arm Town Hall The attendance list is attached. Chairperson, Allan Scott, welcomed all those in attendance. He explained that the purpose of the meeting was to inform community representatives on the status of the Central Newfoundland Waste Management Study. He introduced Wayne Manuel from Bae Newplan. Mr. Manuel did a PowerPoint presentation on the overview of the study and progress report on Phase II. When Mr. Manuel was finished, there was an opportunity for questions and comments from the attendees. Questions: Q. Is the committee looking at the impact of tourism due to the location of the main facility? A. Not at this time. Q. Are you aware that the Town of Norris Arm North is on a ground water supply? A. No. Q. Do you know the leakage from a lined landfill? A. Theoretically they are designed not to leak. There are monitoring systems to control and treat leachate. -2- Q. Why don’t we start small with community recycling etc? A. Cannot meet guidelines as per government strategy (50% reduction) by voluntary involvement. Q. Will this impact the water supply in Norris Arm North? A. Studies will be conducted to determine any impacts on communities and their infrastructure. Q. Should the industrial sector be responsible for covering costs of handling construction and demolition? A. Any product that has a market value will be sold. Tipping fees will cover any handling costs. Q. When the site is chosen, who will police? Are we working with local or provincial regulations? A. -

Waste Management Performance Monitoring Report (August 31, 2014)

Program Summary In response to public consultations, Government released the Newfoundland and Labrador Waste Management Strategy in 2002 with the aim of province-wide modern waste management. The implementation plan and funding commitment were announced in 2007. The primary goals of the strategy are : • Dive rt 50 per cent of solid w aste from landfill ; • Reduction in the number of waste disposal sites by 80 per cent; • Elimination of open burning and incineration; • Phase out of unlined landfills; and • Province wide implementation by 2020. The Strategy envisioned delineating the province into waste management regions which would be governed by regional authorities who would be responsible for the development and implementation of regional waste management plans. At present, it is envisioned that two full service regional waste disposal facilities in the Eastern and Central regions on the island portion of the province will serve as the final disposal sites for all waste generated on the island portion of the province. Remaining regions (non-host) on the island will continue to develop systems to transport waste to the two full service facilities with lined landfills for final disposal. In the interim, local landfill sites will be closed and consolidated to the extent possible. In the area of recycling, a facility opened at Robin Hood Bay in 2011, and a second facility is currently under construction at Norris Arm with an anticipated completion in the Spring of 2015. The Western Region is evaluating whether some recyclables can be more economically processed within the region rather than being transported to Norris Arm, for other non-host regions, recyclables will go to either Robin Hood Bay or Norris Arm. -

BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 P.M. January 18, 2017 Attendance Allan Scott Chair – CRSB Derrick Luff Direct Haul Bruce

Central Newfoundland Waste Management P. O. Box 254, Norris Arm, NL, A0G 3M0 Phone: 709 653 2900 Fax :709 653 2920 Web: www.cnwmc.com E-mail: [email protected] BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 p.m. January 18, 2017 Attendance Allan Scott Chair – CRSB Derrick Luff Direct Haul Bruce Moores Town of Grand Falls Windsor Winston Perry Zone 6 – Indian Bay Claude Elliot Town of Gander Andrew Shea Zone 4 - Fogo Island Marjorie Gaulton Norris Arm North & South Dennis Woolridge Bishops Falls/Botwood/Lewisporte Kevin Butt Zone 3-NWI/Twillingate Sam Windsor Zone 5 - Gander Bay Ed Evans CAO – CNWM Karen White Attwood Manager of Finance/Administration – CNWM Mark Attwood Manager of Operations – CNWM Apologies Robert Elliott Zone 2 -Point Leamington Glenn Arnold Zone 7 – Terra Nova Mike Patey Zone 1 Buchans Jct. Wayne Lynch Service NL Wayne Manual SNC Lavalin 1. Review of previous minutes – December 7, 2016 MOTION: Moved by Claude Elliot to adopt the minutes of December 7, 2016. Seconded by Bruce Moores. M/C 2. Update – Progress Report from SNC-Lavalin RS13 MRF Regional Site Metering for MRF Heat - Cabs are not tied into existing monitoring - Cost $12,000 to add monitor to cabs – to be reviewed and discussed at a later date MRF Sign Off List - SNC Lavalin are required to ensure all warranties, certificates, manuals, etc on the elevator, dust collection system and all other work carried out on the MRF are handed over to CRSB. January 18, 2017 Regional Site - Landfill Expansion Cell #2 – Adams Construction - Roads will be fixed in the Spring 2017.