Dove and Robin Lee Graham - the Voyage of the Dove Round T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Board of Trustees

RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY FROM JUNE 30, 1908 TO JULY 1, 1909 COLUMBUS, OHIO THE CHAMPLIN PRINTING COMPANY 1909 Page 2 is blank Proceedings of the Board of Trustees Ohio State University OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY. CoLUMBus, OHIO, July 31st, 1908. The Board of Trustees met at the call of the President at the University. Present: F. E. Pomerene, President; Guy W. Mallon, 0. T. Corson, John T. Mack, 0. E. Bradfute and Walter J. Sears. * * * * * * * * * * The minutes of the meeting held June 22nd and 23rd were read and approved. * * * * * * * * * * Capt. Alexis Cope presented the following applications for deeds, and the President of the Board was directed to execute the same: Application No. 744-354 of Richard Clayton for 131 acres of land in Survey No. 16098, in Pike County. Application No. 745-355 of Jacob L. Horn for 115 acres of land in Survey No. 16017, in Scioto County. Application No. 746-356 of T!-iomas C. Beatty for 92 acres of land in Survey No. 2624, in Scioto County. Application No. 747-357 of J. H. Somers for 250 acres of land in Survey No. 16202 in Pike County. Application No. 748-358 of Charles E. Shively for 201 acres of land in Survey No. 15847, in Scioto County. Application No. 749-359 of H. H. Jackson & Lena Jackson for 25 acres of land in Survey No. 16210, in Pike County. Application No. 750-360 of John Hawk for 300 acres of land in Surveys Nos. -

PDF < Around the World Single-Handed: the Cruise

TLSSUDBAUI > Around the World Single-Handed: The Cruise of the Islander ~ Doc A round th e W orld Single-Handed: Th e Cruise of th e Islander By Harry Pidgeon Dover Publications Inc., United States, 2012. Paperback. Book Condition: New. New edition. 210 x 136 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. The Islander was my first attempt at building a sailboat, but I don t suppose there ever was an amateur built craft that so nearly fulfilled the dream of her owner, or that a landsman ever came so near to weaving a magic carpet of the sea. So begins this fascinating first-person narrative by a man who did what many dream of but few accomplish. Between 1921 and 1925 Harry Pidgeon circumnavigated the globe in a sailboat of his own construction, experienced many thrilling adventures in the far corners of the world, and relied mainly on his own strength, skill, and resourcefulness to survive. After building his 34-foot yawl (at a cost of $1,000 for materials and a year and a half of hard work), the author sailed from California west across the Pacific to Hawaii in a test voyage. Then, from Los Angeles he cruised to lush and fabled islands the Marquesas, Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji, New Hebrides, and New Guinea. With grace and economy, Mr. Pidgeon describes memorable encounters with native peoples (including suspected cannibals), tribal rites... READ ONLINE [ 7.31 MB ] Reviews Undoubtedly, this is actually the greatest job by any author. This can be for those who statte there was not a worthy of studying. -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 18, 30 June, 26 Jul 2006, 7 Aug 2007, 11 Mar, 21 Apr, 21 May, 8 Jul, 7, 12 Aug 2008, 8, 20 Jan 2009, 23 Feb 2009, 19 & 26 Mar 2009, 23 Sep 2009, 19 Oct, 26, 30 Nov, 7 Dec 2009, 26 May 2010, 7 Jul 2010; 30 Mar, 15 Apr, 3, 28 May, 2 & 14 Jun 2011, 17 Jan 2012. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; SMH, 14 Mar.1848. and Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. -

Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution

REPORT UPON THE CONDmON AxND PROGRESS OF THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM DURING THE YEAR ENDING JUNE MO, 1002. BY RICHARD KATHBUN, ASSISTANT SECRETARY OP THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, IN CHARGE OF THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM. NAT MU.S 1902 1 — T? E P ( ) Jl T THE CONDITION AND PROGKESS OF THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM DURING THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 'M\, VM. Tli('ii.\i,;i> U,\iiii!rN, AsslMdiit SeciU'ldri/ of llic Siiiillisdiiinii Iiisliliilii>n. in churi/f of Ihr l'. S. X<tlio)Kll Miisiiiiil. GENERAL CONSI DKPv A'JK )NS. The United States National Museum had its oriyin in tlu^ act of Cong-ress of 184(3 founding- the kSmithsonian Institution, which made the formation of a museum one of the principal functions of the latter, and jirovided that Whenever suitable avrangementH can l)e made from time to time for their recep- tion, all objects of art and of foreis^n and curious reseai-ch, and all objects of natural history, plants, and geological and mineralogical specimens belunging to the Tnited States, which may be in the city of Washington, in whosesoever custody they may be, shall be deli\ered tu such persons as may be authorized I>y the Board of Regents to receive them, and shall be so arranged and classified in the building erected for the Institution as best to facilitate the examination and study of them; and when- ever new specimens in natural historv, geology, or mineralogy are obtained for the museum of the Institution, l)y exchanges of duplicate specimens, Avhich the Regents may in their discretion make, or by donation, whicli they may receive, or otherwise, the Regents shall catise such new sj^ecimens to be appropriately classed and arranged. -

Runnin' Down a Dream —

RUNNIN' DOWN A DREAM — "Runnin' down a dream, that never would come to me. Workin' on a mystery, chosen to jump from there this season. goin' wherever it leads." Music — Nordic 44 Tom Petty was 'cruising' in a car John McCarthy & Gail Lapetina rather than a sailboat when he penned Bellingham, WA those lyrics. But we think the sentiment John and Gail might seem like an translates perfectly to bluewater voyag- unlikely pair to be heading out across ing, an activity that most of the sailors 3,000 miles of open ocean, as he is a you'll meet in these pages have been self-described "desert rat" from Reno, eagerly anticipating for years. They're and she spent much of her life in Utah. members of the Pacific Puddle Jump But after moving to the Bay, John got so deeply into sailing that he eventually be- came an instructor at Spinnaker Sailing of Redwood City. Gail became a student there, and when she signed up for a club- sponsored flotilla trip to the BVI, who do you suppose was her captain? Their Caribbean romance led to a honeymoon in Tonga, and they've been itching to get back to the sun-kissed isles of the South Pacific ever since. Their Plan A is to cruise south of the equator for six months, then head to Hawaii, and eventually return to their new home base at Bellingham, WA. Charisma — Tayana 37 Bob Johnson & Ann Adams Berkeley, CA "For me the inspiration to do this started when I was 15 reading about Robin Lee Graham and the Dove," ex- plains Bob. -

36Th Annual Guild Conference &

The world’s leading publication for one-namers The quarterly publication of the Guild of One-Name Studies www.one-name.org Volume 12 Issue 1 • January-March 2015 p16 36th Annual Guild Conference & AGM p19 Family Research in the USA All the latest Guild news and updates GUILD OFFICERS CHAIRMAN Box G, 14 Charterhouse Buildings Corrinne Goswell Road, London EC1M 7BA Goodenough Tel: 0800 011 2182 (UK) 11 Wyndham Lane Guild information Tel: 1-800 647 4100 (North America) Allington, Salisbury Tel: 1800 305 184 (Australia) Wiltshire, SP4 0BY Regional Representatives 01980 610835 Email: [email protected] [email protected] The Guild has Regional Reps in Website: www.one-name.org many areas. If you are interested in Registered as a charity in England and becoming one, please contact the Wales No. 802048 VICE CHAIRMAN Regional Rep Coordinator, Gerald Anne Shankland MCG Cooke: 63 Church Lane President Colden Common North Cottage Derek A Palgrave MA MPhil FRHistS FSG MCG Winchester Monmouth Road Hampshire Longhope SO21 1TR Gloucestershire Vice-Presidents 01962 714107 GL17 0QF Howard Benbrook MCG [email protected] Tel: 01452 830672 Iain Swinnerton TD. DL. JP MCG Email: Alec Tritton SECRETARY [email protected] Jan Cooper Greenways Guild Committee 8 New Road Forum The Committee consists of the four Wonersh, Guildford This online discussion forum is open to Officers, plus the following: Surrey, GU5 0SE any member with access to email. You Peter Alefounder 01483 898339 can join the list by sending a message Rodney Brackstone [email protected] -

Accelerated Reader Tests by Title

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 04/26/10, 09:04 AM Kuna Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 8451 100 Questions and Answers about AIDSMichael Ford UG 7.5 6.0 English Nonfiction 17351 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BaseballBob Italia MG 5.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17352 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BasketballBob Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17353 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro FootballBob Italia MG 6.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 17354 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro GolfBob Italia MG 5.6 1.0 English Nonfiction 17355 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro HockeyBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 17356 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro TennisBob Italia MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in SummerBob Olympics Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter OlympicsBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 61265 12 Again Sue Corbett MG 4.9 8.0 English Fiction 14796 The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman MG 4.4 4.0 English Fiction 11101 A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald MG 7.7 1.0 English Nonfiction 907 17 Minutes to Live Richard A. Boning 3.5 0.5 English Fiction 44803 1776: Son of Liberty Elizabeth Massie UG 6.1 9.0 English Fiction 8251 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair MG 5.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 44804 1863: A House Divided Elizabeth Massie UG 5.9 9.0 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 9801 1980 U.S. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM Lakes Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 17351 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BaseballBob Italia MG 5.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17352 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BasketballBob Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17353 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro FootballBob Italia MG 6.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 17354 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro GolfBob Italia MG 5.6 1.0 English Nonfiction 17355 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro HockeyBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 17356 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro TennisBob Italia MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in SummerBob Olympics Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter OlympicsBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 11101 A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald MG 7.7 1.0 English Nonfiction 8251 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair MG 5.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Wayne Coffey MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 523 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 9201 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (Pacemaker)Verne/Clare UG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Catalogue of South Seas

PACIFIC MANUSCRIPTS BUREAU Room 4201, Coombs Building College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia Telephone: (612) 6125 2521 Fax: (612) 6125 0198 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pambu Catalogue of South Seas Photograph Collections Chronologically arranged, including provenance (photographer or collector), title of record group, location of materials and sources of information. Amended 7 July 2010. Date Provenance Region Record Group & Location &/or Source Range Description 1848 J. W. Newland Tahiti Daguerreotypes of natives in Location unknown. Possibly in South America and the South the Historic Photograph Sea Islands, including Queen Collection at the University of Pomare and her subjects. Ref Sydney. (Willis, 1988, p.33; and SMH , 14 Mar.1848. Davies & Stanbury, 1985, p.11). 1857- Matthew New Guinea; Macarthur family albums, Original albums in the 1866, Fortescue Vanuatu; collected by Sir William possession of Mr Macarthur- 1879 Moresby Solomon Macarthur. Stanham. Microfilm copies, Islands Mitchell Library, PXA4358-1. 1858- Paul Fonbonne Vanuatu; New 334 glass negatives and some Mitchell Library, Orig. Neg. Set 1933 Caledonia, prints. 33. Noumea, Isle of Pines c.1850s- Presbyterian Vanuatu Photograph albums - Mitchell Library, ML 1890s Church of missions. Includes some J.W. MSS.1893/ Items 1-4, Box Australia, Board Lindt photographs taken 1(16). of Ecumenical during his trip to the New Mission Hebrides in 1889 & article on Lindt, Age , 23 Sep. 1961. c.1863- Rev. Thomas Fiji Relics and family Mitchell Library, Methodist 1894 Baker photographs. Church of Australasia, Dept. of Overseas Missions, Original: LR 83; Microfilm: CY 4172 (photographs only). -

2002 California State Bar Meeting PULLOUT SECTION

LACBA 2002-03Directory 2002 California State Bar Meeting PULLOUT SECTION OCTOBER 2002, VOL.25, NO.7 / $3.00 Los Angeles lawyers EARN MCLE CREDIT Mark Mermelstein and Judicial Joel M. Athey offer Review of strategies for dealing with witnesses who invoke Arbitration the Fifth Amendment Decisions in civil cases page 35 page 28 Contractual Attorney’s Fees In the Fifth page 12 Distinguishing Dimension Dicta page 17 Offers to Compromise page 22 L EXISN EXIS AND THE L OS A NGELES C OUNTY B AR A SSOCIATION WORKING TOGETHER TO SUPPORT THE LEGAL PROFESSION N O MATTER WHAT THE SIZE OF YOUR FIRM, YOU GAIN STRENGTH IN NUMBERS AS A MEMBER OF THE L OS A NGELES C OUNTY B AR A SSOCIATION. Count on gaining not just the support of the Los Angeles County Bar Association, but LexisNexis as well. By working together, we’re able to offer special benefits to members of the Los Angeles County Bar Association. We realize that the strength of your research is one of your biggest professional advantages. Now putting the best research on the table is easier because LexisNexis offers a selection of online research packages exclusively through the Los Angeles County Bar Association. You can choose from bar member flat rates or pay as you go. New attorneys get a real break right when they need it the most with discounts up to 75% for their online subscriptions. Check out our Special Bar Member Benefits by calling 866.836.8116. See how we make the numbers count. LexisNexis and the Knowledge Burst logo are trademarks of Reed Elsevier Properties Inc., used under license. -

Catharine Mckenty Foreword by Alan Hustak

Expanded Edition RIDING THE ELEPHANT SURVIVAL AND LOVE WITH A BIPOLAR PARTNER CATHARINE MCKENTY FOREWORD BY ALAN HUSTAK Durham, NC Copyright © 2019 Catharine McKenty Riding the Elephant: survival and love with a bipolar partner Catharine McKenty www.neilmckenty.com Published 2019, by Torchflame Books Second edition published 2020 www.torchflamebooks.com Durham, NC 27713 USA SAN: 920-9298 Paperback ISBN: 978-1-61153-346-0 E-book ISBN: 978-1-61153-347-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019945720 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 International Copyright Act, without the prior written permission except in brief quotations embodied in critical ar- ticles and reviews. When you take on an impossible task, the universe conspires to help you. —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe CONTENTS Foreword ..........................................................................vii Preface ..............................................................................ix Early Years – Toronto 1930 - 1952 ....................................1 Donlands Farm .......................................................................4 Lake Simcoe ........................................................................... 21 Bishop Strachan School ........................................................33 Victoria College .................................................................... -

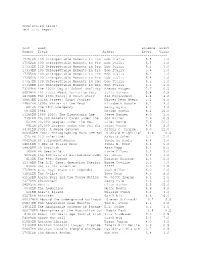

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17351EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.5 1.0 17352EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17353EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.2 1.0 17354EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.6 1.0 17355EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 17356EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.4 1.0 17357EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Sum Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17358EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Win Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 73204EN The 100th Day of School (Holiday Brenda Haugen 2.7 0.5 56578EN 101 Facts About Terrarium Pets Julia Barnes 5.8 0.5 14796EN The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman 4.4 4.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 44802EN 1609: Winter of the Dead Elizabeth Massie 6.1 8.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.1 3.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.2 16.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards under the Jon Buller 2.6 0.5 523EN 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Jules Verne 7.6 20.0 951EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Jules Verne 4.5 2.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 9.0 12.0 900355EN 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edi Richard Brightfiel 4.6 0.5 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 3.1 2.0 30629EN 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola 4.4 1.0 14911EN 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M.