Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

1 Slapstick After Fordism: WALL-E, Automatism and Pixar's Fun Factory Animation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Slapstick After Fordism: WALL-E, Automatism and Pixar’s Fun Factory animation: an interdisciplinary journal 11:1 (March 2016) Paul Flaig, University of Aberdeen In his recent The World Beyond Your Head, Matthew Crawford (2015) argues for a reclaiming of the real against the solipsism of contemporary, technologically cocooned life. Opposing digitally induced distraction, he insists on confronting the contingencies of an obstinately material, non- human world, one that rudely insists beyond our representational schema and cognitive certainties. In this Crawford joins an increasingly vocal chorus of critics questioning the ongoing transformation of human subjectivity via digital mediation and online connectivity (see Turkle 2012 and Carr 2011). Yet to mount this critique Crawford turns to a surprising example: Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, the Disney Channel’s first entirely computer animated television series, running from 2006 to the present. Given the proclaimed philosophical stakes of his book, which draws on Heidegger’s concept of “Being-in-the-World” and critiques Kantian Aufklärung, what peeks Crawford’s interest in Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, aimed at teaching pre-schoolers rudimentary concepts, facts and vocabulary? Specifically, it is the contrast between Clubhouse and Mickey’s first adventures in Disney shorts of the twenties and thirties. In the latter, “the most prominent source of hilarity is the capacity of material stuff to generate frustration,” thus offering to its viewers “a rich phenomenology of what it is like to be an embodied agent in a world of artifacts and inexorable physical laws” (70). -

Playaway Pre-Loaded Audiobooks Are the Best Way to Listen, Unplugged and Uninterrupted

The iconic bassist and co-founder of the Red Hot Chili Peppers tells his fascinating origin story, complete with all the dizzying highs and the gutter lows you’d want from an LA street rat turned world-famous rock star. In Acid for the Children, Flea takes listeners on a deeply personal and revealing tour of his formative years, spanning from Australia to the New York City suburbs to, finally, Los Angeles. Through hilarious anecdotes, poetical meditations, and occasional flights of fantasy, Flea deftly chronicles the experiences that forged him as an artist, a musician, and a young man. His dreamy, jazz-inflected prose makes the Los Angeles of the 1970s and 80s come to gritty, glorious life, including the potential for fun, danger, mayhem, or inspiration that lurked around every corner. It is here that young Flea, looking to escape a turbulent home, found family in a community of musicians, artists, and junkies who also lived on the fringe. He spent most of his time partying and committing petty crimes. But it was in music where he found a higher meaning, a place to channel his frustration, loneliness, and love. This left him open to the life-changing moment when he and his best friends, soul brothers, and partners-in-mischief came up with the idea to start their own band, which became the Red Hot Chili Peppers. With an original poem by Patti Smith introducing this unique memoir, Acid for the Children is the debut of a stunning new literary voice, whose prose is as witty, entertaining, and wildly unpredictable as the author himself. -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

Neo-Hollywood: a Broken Utopia Erasing the Human Spirit An

Neo-Hollywood: A Broken Utopia Erasing the Human Spirit An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Ty Stratton Thesis Advisor Elizabeth Dalton Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation May 2020 Abstract The questions tackled in this film script deal with those concerning representation and how fragile the barriers between reality and an act really are. In this thesis I wrote four scenes of a dystopian film and analyzed the fallout of a film-icon obsessed world. The script follows main character and actor, Gunner, who runs away from a Hollywood he no longer understands in 2090. Leaving could mean freedom, but the risk is that he dies at the hands of a disillusioned population who are incapable of viewing celebrities as people. At the same time, he runs from a cult-like troupe of actors who are ensuring his safety in a compound hidden from the rest of America. Inspired by Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, I continue his postmodern comments on representation and how meaning is steadily being dissolved from the human spirit. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Elizabeth Dalton for her insights and ability to think within the world I created. I would like to thank Madison for the motivation, Dr. Berg for the inspiration, and my friends for putting up with my dystopian musings for 4+ years Process Analysis for Neo-Hollywood The Neo-Hollywood film script was created in during the spring 2020 semester for my thesis at Ball State University. Film is a genre that continually inspired my artistic endeavors during my academic career. -

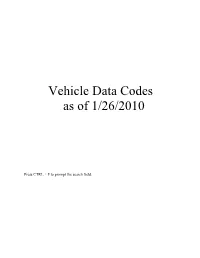

H:\My Documents\Article.Wpd

Vehicle Data Codes as of 1/26/2010 Press CTRL + F to prompt the search field. VEHICLE DATA CODES TABLE OF CONTENTS 1--LICENSE PLATE TYPE (LIT) FIELD CODES 1.1 LIT FIELD CODES FOR REGULAR PASSENGER AUTOMOBILE PLATES 1.2 LIT FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 1.3 LIT FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES AND SNOWMOBILES 1.4 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 1.5 LIT FIELD CODES FOR SPECIAL LICENSE PLATES 2--VEHICLE MAKE (VMA) AND BRAND NAME (BRA) FIELD CODES 2.1 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES 2.2 VMA, BRA, AND VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, LIGHT- DUTY TRUCKS, AND PARTS 2.3 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT AND CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.4 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT AND FARM EQUIPMENT PARTS 2.5 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR MOTORCYCLES AND MOTORCYCLE PARTS 2.6 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR SNOWMOBILES AND SNOWMOBILE PARTS 2.7 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRAILERS AND TRAILER PARTS 2.8 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES FOR TRUCKS AND TRUCK PARTS 2.9 VMA AND BRA FIELD CODES ALPHABETICALLY BY CODE 3--VEHICLE MODEL (VMO) FIELD CODES 3.1 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AUTOMOBILES, LIGHT-DUTY VANS, AND LIGHT-DUTY TRUCKS 3.2 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ASSEMBLED VEHICLES 3.3 VMO FIELD CODES FOR AIRCRAFT 3.4 VMO FIELD CODES FOR ALL-TERRAIN VEHICLES 3.5 VMO FIELD CODES FOR CONSTRUCTION EQUIPMENT 3.6 VMO FIELD CODES FOR DUNE BUGGIES 3.7 VMO FIELD CODES FOR FARM AND GARDEN EQUIPMENT 3.8 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GO-CARTS 3.9 VMO FIELD CODES FOR GOLF CARTS 3.10 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED RIDE-ON TOYS 3.11 VMO FIELD CODES FOR MOTORIZED WHEELCHAIRS 3.12 -

Pariah (2011): Coming out in the Middle

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies 2015 Pariah (2011): Coming Out In The Middle Patricia White Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Patricia White. (2015). "Pariah (2011): Coming Out In The Middle". US Independent Film After 1989: Possible Films. 133-143. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/50 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. chapter 13 Pariah (2011): Coming Out in the Middle Patricia White arly headlines from the 2011 Sundance Film Festival trumpeted Focus EFeatures’ acquisition of Dee Rees’ Pariah after the film screened on the festival’s opening night. The deal offered by the specialty division of Universal was reported to be in the ‘seven figure range’ (Fleming 2011). The film’s executive producer Spike Lee, the launch at the hit- making festival and the studio- affiliated distributor put this case study firmly within the realm of commercial- independent cinema that has evolved in the US since the 1980s (see Perkins 2012). Yet Pariah is as oriented toward community as it is toward commerce, and festival buzz is only one dimension of its publicity. Made by first- time director Dee Rees for under US$500,000, Pariah tells the story of a sensitive African American lesbian’s coming of age and to terms with parental and peer expectations in current- day Brooklyn. -

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Short Story

FOUR OUT OF TEN WINS! The record speaks for itself! There can be no question as to which company won the Quigley Short Subject Annual Exhibitor Vote. The results appeared on Page 21 of Motion Picture Herald, issue of Jan. 11, 1941, as follows: M-G-M 4 Next Company 3 Next Company 1 Next Company 1 Next Company 1 Leadership means doing the unusual first! Here's M-G-M's newest idea: Watch for this great short Tapping an unexplored field, subject! Short story masterpieces at last "THE On the screen— the first is HAPPIEST MAN 'THE HAPPIEST MAN ON EARTH" ON EARTH" One of M-G-M's most important steps featuring In years of short subject leadership. PAUL KELLY VICTOR KILLIAN Get ready for PETE SMITH'S "PENNY TO THE RESCUE," another Prudence Penny cookery The O. Henry Memorial comedy in Technicolor. It's swell. Also CAREY WILSON'S "MORE ABOUT NOSTRADAMUS/' Award -Winning Short Story a sequel to the prediction short that fascinated the nation. Scanned from the collections of The Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation www.loc.gov/avconservation Motion Picture and Television Reading Room www.loc.gov/rr/mopic Recorded Sound Reference Center www.loc.gov/rr/record 7 Quicker'n a wink' playing on the current program with 'Escape' is proving a sensation of unusual quality. Comments from our patrons are most enthusiastic. The sub- ject is a rare blending of scientific and entertaining units into an alto- gether delightful offering that is definitely boxoffice. This is an as- sured fact based on the number of calls we are receiving to inquire the screening time of the subject." BRUCE FOWLER, Mgr. -

Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By

Animating Transcultural Communities: Animation Fandom in North America and East Asia from 1906–2010 By Sandra Annett A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Film, and Theatre University of Manitoba Winnipeg © 2011 Sandra Annett Abstract This dissertation examines the role that animation plays in the formation of transcultural fan communities. A ―transcultural fan community‖ is defined as a group in which members from many national, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds find a sense of connection across difference, engaging with each other through a mutual interest in animation while negotiating the frictions that result from their differing social and historical contexts. The transcultural model acts as an intervention into polarized academic discourses on media globalization which frame animation as either structural neo-imperial domination or as a wellspring of active, resistant readings. Rather than focusing on top-down oppression or bottom-up resistance, this dissertation demonstrates that it is in the intersections and conflicts between different uses of texts that transcultural fan communities are born. The methodologies of this dissertations are drawn from film/media studies, cultural studies, and ethnography. The first two parts employ textual close reading and historical research to show how film animation in the early twentieth century (mainly works by the Fleischer Brothers, Ōfuji Noburō, Walt Disney, and Seo Mitsuyo) and television animation in the late twentieth century (such as The Jetsons, Astro Boy and Cowboy Bebop) depicted and generated nationally and ethnically diverse audiences. -

1144 05/16 Issue One Thousand One Hundred Forty-Four Thursday, May Sixteen, Mmxix

#1144 05/16 issue one thousand one hundred forty-four thursday, may sixteen, mmxix “9-1-1: LONE STAR” Series / FOX TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX TELEVISION 10201 W. Pico Blvd, Bldg. 1, Los Angeles, CA 90064 [email protected] PHONE: 310-969-5511 FAX: 310-969-4886 STATUS: Summer 2019 PRODUCER: Ryan Murphy - Brad Falchuk - Tim Minear CAST: Rob Lowe RYAN MURPHY PRODUCTIONS 10201 W. Pico Blvd., Bldg. 12, The Loft, Los Angeles, CA 90035 310-369-3970 Follows a sophisticated New York cop (Lowe) who, along with his son, re-locates to Austin, and must try to balance saving those who are at their most vulnerable with solving the problems in his own life. “355” Feature Film 05-09-19 ê GENRE FILMS 10201 West Pico Boulevard Building 49, Los Angeles, CA 90035 PHONE: 310-369-2842 STATUS: July 8 LOCATION: Paris - London - Morocco PRODUCER: Kelly Carmichael WRITER: Theresa Rebeck DIRECTOR: Simon Kinberg LP: Richard Hewitt PM: Jennifer Wynne DP: Roger Deakins CAST: Jessica Chastain - Penelope Cruz - Lupita Nyong’o - Fan Bingbing - Sebastian Stan - Edgar Ramirez FRECKLE FILMS 205 West 57th St., New York, NY 10019 646-830-3365 [email protected] FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT 150 W. 22nd Street, Suite 1025, New York, NY 10011 917-484-8900 [email protected] GOLDEN TITLE 29 Austin Road, 11/F, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China UNIVERSAL PICTURES 100 Universal City Plaza Universal City, CA 91608 818-777-1000 A large-scale espionage film about international agents in a grounded, edgy action thriller. The film involves these top agents from organizations around the world uniting to stop a global organization from acquiring a weapon that could plunge an already unstable world into total chaos. -

Weekend Box Office Results… 4/2 – 4/4 with Comments by Paul Dergarabedian, Comscore Per Theatre Rank Title Week Theatres Wknd $ Total $ Average $ 1 Godzilla Vs

Monday, April 5, 2021 | No. 162 Happy 95th birthday to legendary filmmaker Roger Corman, born on April 5, 1926. Known as "The Pope of Pop Cinema", Corman began his career in the 1950’s as a writer, director and producer of low-budget genre films, including westerns, horror and sci-fi cult classics such as Highway Dragnet (1954), The Day the World Ended (1955), It Conquered the World (1956), Not of This Earth (1957) and House of Usher (1960). He became the leading filmmaker for American International Pictures, the producer-distributor of 1950’s and 60’s low-budget, independent films which were popular as drive-in double features. At AIP, Corman’s technique was to work very fast and very cheap, often shooting multiple films back-to-back on the same location. AIP made the most of Corman's production skills, frequently beginning a film’s development by creating a poster and then showing it to movie fans to gauge interest. Corman created a factory for micro- budget filmmaking which gave break-in opportunities to young directors and actors at the start of Happy Birthday to their careers. Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Ron Howard, Peter Bogdanovich, James Roger Corman – Click to Play Cameron, Joe Dante and Jonathan Demme all learned their filmmaking techniques by working on projects with Corman. Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Charles Bronson, Dennis Hopper, Talia Shire, Sandra Bullock, Diane Ladd, William Shattner and Robert De Niro gained visibility as young actors in Corman’s low-budget productions. In 1960, Corman directed for AIP the horror film House of Usher, starring Vincent Price, based on an 1839 short story by Edgar Allan Poe.