Fishing. with Contributions from Other Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributions to the History of the Guttural Sounds in English

129 V.-CONTRIRUTIOKS TO THE HISTORY OF THE GUTTURA4L SOUPJDS IN ENGLISH. By HEXRY CECILWYI.~, of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. [&ad at the Meeting of ;he Philologual Society on Friday, April 14, l8Q9.1 PREFATORYREYAEKS. TEE following is a study and history of four classes of English sounds :- 1. Old Engl. u. Back (guttural) and front (palatal). 2. Old Engl. a. Back and front. 3. Old Engl. 5. 4. Old Engl. h. Back and front. All these sounds are here considered only as occurring medially sod finally. My remarks are based upon an oxtensire collection of forms which I have cnlled with no little labour from O.E. and X.E. texts, and from modern dialect glossaries. My collections of Literary English words are from Professor Skeat’s larger Etymological Dictionary. I shall discuss the pronunciation of the sounds which I hare mentioned in O.E., and it will be seen that in several points I venture to differ from the commonly received views of McsRieurR Kluge, Sievere, and Biilbring. I shall then investigate the M.E. forms of O.E. o, a, q,etc., as they appear in the most important texts of M.E. For this purpose tho word-lieta are arranged chronologically and geographically. so aa to show at once the historical development of the sounds, and their distribution in the varioue M.6. dialects. With regard to the modern dialects, the arrangement is chiefly geographical, beginning with the North and working down to the extreme South of England. The order of the lists ie as far aa posuible from west to east. -

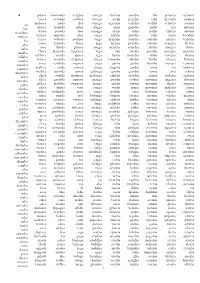

Inter-State Cipher

JffTEjV^STATE CIPHER ARRANGED BY H. K. PRATT Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Duke University Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/interstatecipherOOprat PREFACE The following Code has been arranged for general use of the Fruit Shippers and Jobbers of these United States. The names of the Jobbers and Fruit Ship- pers who use this Code are indexed in the hack of the book. Additional names and corrections will be sent you from time to time. We would kindly ask you to put on your letterhead, "We Use the Inter-State Cipher," so as to encourage its general use. While no guarantee or special recommend is made of the parties using this Code, I am glad to say they are considered among the best Ship- pers and Jobbers in this country. Address H. K. PRATT Price, $2.00 Minneapolis Numerals and Prices In Dollars and Cents. It is understood where prices are implied the following figures are in dollars and cents, pointing off two places to the left for cents, otherwise they stand for numerals. Aback i/8 Abject 5Vi Abacot Vi Abjure 514 Abacus % Ablaze 5% Abaft 14 Ablen 6 Abandon % Ablist 614 :; Abanet t Ablude 6V2 Abase % Abluent 6% Abash 1 Abnet 7 Abashing 1*4 Aboard 7%. Abbassi I1/2 Abolish 71/2 Abate 1% Abomis 7% Abatis.. 2 Aborigin 8 Abaum 2M Abound 8V4 Abbe 2Y2 Above 8V2 Abbess 2% Abridge 8% Abbott 3 Abroad 9 Abdals 3V4 Abrogate 9Vi Abdest 3V2 Abrook 9V2 Abduct 3% Abrupt 9 a 4 Abear 4 Abscess 10 Abele 4V4 Abscind IOV2 Abet 4V2 Abscond 11 :; 1 Abhor 4 , Absence II 2 Abide o Absolve 12 Numerals and J 'rices. -

BRITISH ENGLISH a to ZED H

BRITISH ENGLISH A TO ZED h BRITISH ENGLISH A TO ZED h Third Edition NORMAN W. SCHUR Revised by EUGENE EHRLICH and richard ehrlich BRITISH ENGLISH A TO ZED, THIRD EDITION Third edition copyright © 2007 by Eugene Ehrlich and the estate of Norman W. Schur. Original edition copyright © 1987, 2001 by Norman W. Schur. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schur, Norman W. British English A to Zed / Norman W. Schur with Eugene Ehrlich.—Rev. and updated ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8160-6455-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. English language—Great Britain—Dictionaries. 2. Great Britain— Civilization—Dictionaries. I. Ehrlich, Eugene H. II. Title. PE1704 .S38 2001 423′.1—dc21 00-060059 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at 212/967-8800 or 800/322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Cover design by Dorothy M. Preston Printed in the United States of America MP FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Notes on the Ethnology of the Indians of Puget Sound

T¥P> IAN NOTES /Vrr»fllWPAND MONOGRAPHS ho, ?? Miscellaneous Series No. 59 NOTES ON THE ETHNOLOGY OF THE INDIANS OF PUGET SOUND BY T. T. WATERMAN NEW YORK MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN HEYE FOUNDATION 1973 INDIAN NOTES AND MONOGRAPHS NOTES ON THE ETHNOLOGY OF THE INDIANS OF PUGET SOUND BY T. T. WATERMAN NEW YORK MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN HEYE FOUNDATION 1973 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CARD NO. 72-88406 price: $3.50 PRINTED IN GERMANY BY J.J. AUGUSTIN, GLUCKSTADT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Foreword v Introduction vii Basketry and textiles i Baskets i General remarks i Varieties of baskets and their manufacture 7 Description of noteworthy specimens .... 1 Ornamentation 17 Matting 24 Bags 29 Blankets 30 The Spindle 37 Pack-straps 37 Wooden objects 39 Dishes and spoons 39 Roasting sticks and skewers 41 Cradle-boards 42 Implements 46 Canoe-paddles 46 Adzes 48 Mauls 50 Digging-sticks 51 Berry-pickers 53 iii Table of contents Hunting implements, nets, and traps 55 Bows 55 Fish-spears 55 Herring-rakes 61 Bird spears 62 Fish weirs 63 Dip nets 64 Fish hooks 65 Aerial nets for ducks 67 Games 73 The potlatch 75 Relations between the culture of Puget Sound and that of other areas 83 Conclusion 91 Bibliography 92 ILLUSTRATIONS MAPS The Pacific Northwest 97 Puget Sound Region (Detail) 98 IV FOREWORD Dr. Thomas Talbot Waterman (1886-1936), was a field collector for the Museum of the American Indian from 1919 to 1922, and his experiences in the Pacific Northwest are in large part the basis for much of the data included herein. -

Bowlker's Art of Angling : Containing Directions for Fly-Fishing, Trolling

^ vPYa ^^i ^ w THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTED BY PROF. CHARLES A. KOFOID AND MRS. PRUDENCE W. KOFOID i /. AA/.^-i^"^ ' 0^^ '' ^ BOWLKER'S AET OF ANaLINa. 1B0WL'J^1M,3 MlT 0yM^WlsTR9. ART OF ANGLING, CONTAINING DIRECTIONS FOR FLY-FISHING, TEOLLING, MAKma AETIPICIAL FLIES, &c. WITH A LIST OF THE MOST CELEBRATED FISHING STATIONS IN NORTH WALES. ' Celate cibis uncos fallacibus hamos." Ovid. A NEW EDITION, EEYISED. LUDL W: FEINTED A^D SOLD BY B. JONES, BROAD STEEET. LONDON: LONGMAN, BEOWN, & CO. 1854. <^ . Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://wwvv.archive.org/details/bowlkersartofangOObowlrich issf DESCRIPTION OF THE FRONTISPIECE. No. 1. Red Fly. 2. Blue Dun. 3. March Brown. 4. Cowdung Fly. 5. Stone Fly. 6. Granam, or Green Tail. 7. Spider Fly. 8. Black Gnat. 9. Black Caterpillar. 10. Little Iron Blue. 11. Yellow Sally. 12. Canon, or Down Hill Fly. 13. Shorn Fly, or Marlow Buzz. 14. Yellow May Fly, or Cadow. 15. Grey Drake. 16. Orl Fly. 17. Sky Blue. 18. Cadis Fly. 19. Fern Fly, 20. Red Spinner. 21. Blue Gnat. 22 & 23. Large Red and Black Ants. 24. Hazel Fly, or Welshman's Button. 25. Little Red and Black Ants. 26. Whirling Blue. 27, Little Pale Blue. 28. Willow Fly. 29. White Moth. 30. Red Palmer. i^USSll CONTENTS. ALPINE Trout or Gilt Charr, remarks on, page 36. Barbel, remarks on, 79 ; baits for, 80. Barometer, rules for judging of the, 151. Bleak, remarks on, 89. Bream, remarks on, 77 ; baits for, 78. -

Report on the Eel Stock and Fishery in the Netherlands 2008

460 EIFAC/ICES WGEEL Report 2008 Report on the eel stock and fishery in the Netherlands 2008 NL.A Authors Willem Dekker, IMARES, Institute for Marine Resources and Ecosystem Studies, PO Box 68, 1970 AB IJmuiden, the Netherlands. Tel. +31 255 564 646. Fax: +31 255 564 644 [email protected] Reporting Period: This report was completed in August 2008, and contains data up to 2007 and recruitment data for 2008. Contributors to this report: Jan Klein Breteler, Vivion, Händelstraat 18, 3533 GK Utrecht, The Netherlands. [email protected] NL.B Introduction NL.B.1 Status of this report In 2002 (ICES 2003), the EIFAC/ICES Working Group on eels recommended that member countries should report annually on trends in their local populations and fisheries to the Working Group. In 2003 (ICES 2004), detailed data reports per country were annexed to the working group report, which have subsequently been updated, refined and restructured to match the set‐up of the EU Data Collection Regulation. FAO/ICES (2007) is the most recent version. This report on the status of and trend in the eel stock in the Netherlands updates the information presented before. NL.B.2 General overview of fisheries Eel fisheries in the Netherlands occur in coastal waters, estuaries, larger and smaller lakes, rivers, polders, etc. The total fishery involves just over 200 companies, with an estimated total catch of nearly 1000 tonnes. Management of eel stock and fisheries has been an integral part of the long tradition in manipulating water courses (polder con‐ struction, river straightening, ditches and canals, etc.). -

Rhyming Scrabble Dictionary Based on OSPD4

A pataca hammada zooglea omega farinha ascidia ilia petunia aphasia bacca armada cochlea fanega aloha pygidia cilia hryvnia aplasia aa malacca nada ilea senega agrapha conidia sedilia sequoia acrasia baa mecca panada pilea dagga epha gonidia milia pia entasia markkaa wicca posada olea quagga alpha oidia pallia tilapia astasia rufiyaa felucca pintada plea saiga sulpha peridia folia sepia woodsia ba yucca tostada perinea taiga nympha basidia acholia anopia babesia aba caeca lambda tinea giga hypha pyxidia scholia senopia freesia baba ceca kheda guinea amiga murrha scandia abulia sinopia silesia indaba theca alameda hyponea viga sha alodia peculia meropia amnesia jellaba ootheca reseda apnea alga kasha melodia dulia ectopia atresia casaba seneca zenaida dyspnea belga tamasha allodia thulia utopia fuchsia piasaba areca candida eupnea anga pasha podia aboulia myopia camisia cassaba arabica cnida cornea fanga bugsha cardia amia ria banksia mastaba modica querida usnea galanga geisha giardia lamia aria celosia abba chica corrida ipomoea malanga rikisha exordia zamia sudaria agnosia zareeba silica gravida apnoea manga poisha codeia anaemia angaria abrosia gleba gallica matilda eupnoea panga orisha pereia uraemia sharia anopsia ameba plica banda toea sanga wisha mafia pyaemia malaria tarsia amoeba replica wakanda zoea tanga ricksha tafia bohemia talaria cassia zareba mica panda pea bubinga buqsha ratafia anemia velaria quassia copaiba vomica veranda cowpea anhinga aphtha maffia viremia filaria ossia ceiba formica vanda area linga naphtha raffia coremia -

Aa Ac Ad Ag Ah Ai Ak Al Am an Ap Ar As at Au Ax Ay Az Ba Bc Bd Be Bi Bk Bo

aa ac ad ag ah ai ak al am an ap ar as at au ax ay az ba bc bd be bi bk bo bp bs bx by ca cb cc cd ce ci cm co cs ct cu cv cy cz da db dc de dj dl do dr dt du dv dx dy dz ea ed eg eh el em en er es et eu ex fa fc fd fe ff fl fm fr fs ft fu ga gb ge gi gm go gp gu ha he hi ho hp hq hr hz ia ic id ie if ii il in ip iq ir is it iv ix jr kc kg kl km ko ks ku kw ky la lb li ll ln lo lp lt lu lw ma mc md me mi mo mr ms mu my na nb nc nd ne nf nh ni nj nm no np nr nt nu nv nw ny od of oh ok on op or os ow ox oz pa pc pd pe pg ph pi pj pl pm po pp pq pr ps pt pu px qt ra rd re rh rn ro rr rt rv rx sa sc sd se sf sh so sq st sw ta tb ti tn to tt tv tx ua uh uk un up us ut uv va vc vd vi vp vt wa we wi wp wt wv wy xi xs xt xv xx yd ye yo yr zn abc abe ace act add ado aft age ago aha aid ail aim air alb ale ali all alm alp alt ama ami amp amt amu amy ana and ani ann ant any ape apo apt arc are ark arm art ash ask asp ass ate aug auk aut ave awe awl awn axe aye baa bad bag bah ban bar bas bat bay bed bee beg ben bet bey bib bid big bin bio bit boa bob bog bon boo bop bow box boy bra bro bud bug bum bun bur bus but buy bye byu cab cad cam can cap car cat caw cay ceo chi cio cit cob cod cog col com con coo cop cot cow coy cpu crt cry cub cud cue cul cum cup cur cut dab dad dam dan day deb dec def dei del den des dew did die dig dim din dip dir dna doa doc doe dog don dos dot dow doz dry dub dud due dug dun duo dup dye ear eat ebb ecg eeg eel eft egg ego eke elf elk ell elm emu enc end ene eon epa era ere erg ese esp est eta etc eve ewe ext eye fad fag -

ISLAND REPORTER, Snow Crab Legs of Bitter, Dry Desert

•F1IB RAUSCHENBERG 1 COOKING POSTCARD FROM mm i UP SOMETHING Cl LONDON Jo j1 WITH CASTRO .-A 1 ~2A — 1B BLACK HISTORY MONTH — 1C FEBRUARY 25, 1988 VOLUME 16 island NUMBER 15 4 SECTIONS, 100 PAGES REPORTER SANIBEL AND CAPTIVA, FLORIDA FIRST WITH THE NEWS 50CENTS Traffic: how much can island residents stand? Survey will help find "I thinkit's unlikely that the city council will require it," city manager Gary Price said of the solutions to congestion alternate route. Council does not want to change what Price calls the "ambiance" of By Matt Perez Periwinkle Way. hat is the level of service Sanibel resi- To residents, Price agrees, that ambiance in- dents expect from their roads, and cludes winter months of traffic resembling a Wwhat accompanying level of disuption stiff, dead snake on Sanibel's main drag. are they willing to accept? "And we're recognizing that and accept that Those two questions are responsible for the as a given," Price said. first traffic circulation study ordered by the Ci- "Please go down to the right for the roadside ty of Sanibel since the turn of the decade. interview," said researcher Elizabeth Archer. During brief interviews with Sanibel Her questions were answered patiently by most Causeway motorists Feb. 18, researchers from drivers, she said, though many ignored Sanibel David Plummer and Associates, Inc., con- Police's detour at the causeway weigh station sultants for the city, asked drivers about their and weaved through pylon barricades. destination on Sanibel and Captiva. Also, con- "I got stuck in that survey yesterday," said sultants hoped to find out from where motorists 7-Eleven Foodstore clerk Pat Henry.