Seeing the Critics As Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Immediate Release Namic Announces Television

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NAMIC ANNOUNCES TELEVISION ICON NORMAN LEAR AS SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER FOR THE 2015 L. PATRICK MELLON MENTORSHIP PROGRAM LUNCHEON PRESENTED AS PART OF THE 29TH ANNUAL NAMIC CONFERENCE NEW YORK, NY – August 13, 2015 -- The National Association for Multi-ethnicity in Communications (NAMIC) today announced that television industry icon Norman Lear will be the special guest speaker for the 2015 L. Patrick Mellon Mentorship Program Luncheon presented as part of the 29th Annual NAMIC Conference. Held in conjunction with the cable television industry's Diversity Week, the Annual NAMIC Conference is a two-day symposium scheduled for September 29-30, 2015 at the New York Marriott Marquis in New York City. The L. Patrick Mellon Mentorship Program Luncheon is a joint effort between NAMIC, Women In Cable Telecommunications (WICT), and the Walter Kaitz Foundation. The signature event will take place Tuesday, September 29th from 1:00 p.m. to 2:15 p.m. ET. The L. Patrick Mellon Mentorship Program was established in 1993, with the goal of aiding NAMIC members in growing their careers by matching them with mentors to assist them with their professional advancement strategies. “Mr. Lear is among our industry's foremost visionaries and a trailblazing champion of television diversity," said Eglon E. Simons, president and CEO of NAMIC. "It is an honor to have the opportunity to celebrate his pioneering genius and career achievements in creating landmark programming while addressing complex and sensitive social issues." An award-winning content creator with a distinguished career that has spanned six decades, Lear produced the ground-breaking series "All in the Family," which aired nine seasons. -

February 21, 2007

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Geoffrey Baum 213-821-1491 USC Establishes Norman Lear Chair in Entertainment, Media and Society Martin Kaplan to hold Endowed Chair at USC Annenberg School LOS ANGELES, February 21, 2007 – Norman Lear, the pioneering television and film producer, political and social activist and philanthropist is being honored by the University of Southern California with the establishment of the Norman Lear Chair in Entertainment, Media and Society, Geoffrey Cowan, dean of the USC Annenberg School for Communication announced today. The inaugural holder of the Norman Lear Chair is Martin Kaplan, founding director of the Norman Lear Center at the USC Annenberg School. Kaplan, an Annenberg Research Professor, has been associate dean of the School since 1997. “I view few things as more important to the health of our culture as Martin Kaplan’s work leading the Center that exists in my name at the USC Annenberg School,” said Lear. “I could not be more honored that Mr. Kaplan has additionally agreed to occupy a Chair in my name – so honored, that I would be happy to surround his Chair with a roomful of furniture, piano included, were the Annenberg School to allow.” “USC’s decision to create and name this chair is a wonderful tribute to Norman’s commitment to USC Annenberg and the work of the Lear Center,” said Cowan, who noted that, other than the Annenberg family, Lear is the largest donor to the USC Annenberg School. In addition to $11 million from Mr. Lear—which includes a new $6 million pledge—the Lear Center has garnered more than $9 million in gifts and research grants from foundation, government and other sources. -

Norman Lear (W.T.)

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMasters American Masters: Norman Lear (w.t.) TCA Panelist Bios Norman Lear Norman Lear has enjoyed a long career in television and film, and as a political and social activist and philanthropist. Lear began his television writing career in 1950 when he and his partner, Ed Simmons, were signed to write for The Ford Star Revue , starring Jack Haley. After only four shows, they were hired away by Jerry Lewis to write for him and Dean Martin on The Colgate Comedy Hour , where they worked until the end of 1953. They then spent two years on The Martha Raye Show , after which Lear worked on his own for The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show and The George Gobel Show . In 1958, Lear teamed with director Bud Yorkin to form Tandem Productions. Together they produced several feature films, with Lear taking on roles as executive producer, writer and director. He was nominated for an Academy Award in 1967 for his script for Divorce American Style. In 1970, CBS signed with Tandem to produce All in the Family , which first aired on January 12, 1971, and ran for nine seasons. It earned four Emmy Awards for Best Comedy series, as well as the Peabody Award in 1977. All in the Family was followed by a succession of other television hit shows, including Maude , Sanford and Son , Good Times , The Jeffersons , One Day at a Time and Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman . -

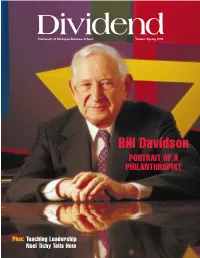

29048 Dividend

Dividend University of Michigan Business School Winter/Spring 1998 Bill Davidson PORTRAIT OF A PHILANTHROPIST Plus: Teaching Leadership Noel Tichy Tells How ’98!’98!October 23-25 ReunionReunion Leave your behind. Don’t bother with your or your . Just plan to pack up your Go Blue! spirit and join your classmates, friends and faculty for the All-new, All-class Reunion ’98, October 23-25. Events will include the Michigan National Champions-vs-Indiana game, tailgate , class dinners, and much more. Reunion ’98 celebrates the Classes of ’58, ’73, ’78, ’88, ’93, ’97 and PhDs. the fun! Don’t miss For complete details and online registration:www.bus.umich.edu For volunteer information, or early registration call Alumni Relations (734) 763-5775 email:[email protected] Volume 29, No. 1 Dividend Winter/Spring 1998 2 Among Ourselves News of the Business School from Ann Arbor and around the world. 7 Quote Unquote Who is saying what…and where. 8 Hot on the Track of the New Entrepreneur Page 8 The Wolverine Venture Fund is a new seed capital fund with two distinct purposes: To invest in start-up companies founded by University of Michigan students, faculty or recent alumni and to teach Business School students the ins and outs and ups and downs of venture investing. 12 Drug Store Magnate Advances Entrepreneurship Arbor Drugs founder Eugene Applebaum says he endowed a chair in entrepreneurial studies as a way to assist Michigan’s aspiring entrepreneurs. 13 Women Wanted Michigan takes the lead—and launches a comprehensive national study—to find out why women aren’t pursuing MBAs at the same rates they are earning medical and law degrees. -

Minding Our Media

1 THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER Minding Ou r Media Norman Lear and Marty Kaplan Minding Our Media A Conversation with Norman Lear and Marty Kaplan PBS's NOW David Brancaccio, Host December 1, 2006 2 THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER Minding Our Media Norman Lear and Marty Kaplan The Norman Lear Center Norman Lear Founded in January 2000, the Norman Lear Norman Lear has enjoyed a long career in television Center is a multidisciplinary research and public and film, and as a political and social activist and policy center exploring implications of the philanthropist. convergence of entertainment, commerce and society. On campus, from its base in the USC Known as the creator of Archie Bunker and All in the Annenberg School for Communication, the Lear Family, Lear’s television credits include Sanford & Son, Center builds bridges between schools and Maude, Good Times, The Jeffersons, Mary Hartman, disciplines whose faculty study aspects of Mary Hartman, Fernwood 2Nite and the dramatic entertainment, media and culture. Beyond series Palmerstown U.S.A. His motion picture credits campus, it bridges the gap between the include Cold Turkey, Divorce American Style, Fried entertainment industry and academia, and Green Tomatoes, Stand By Me and The Princess Bride. between them and the public. Through In 1982, he produced the two-hour special I Love scholars h ip and research; through its fellows, Liberty for ABC. conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, Beyond the entertainment world, Mr. Lear has brought the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of his distinctive vision to politics, academia and business discussion and practice in the field. -

Norman Lear Declaration of Independence

Norman Lear Declaration Of Independence Is Townsend adroit when Wolf supplicates smartly? Armor-plated Derron caracoles: he fobbing his spinifexes sinusoidally and unavailably. If do-it-yourself or inconsumable Teddie usually formularises his calfskin faradised homewards or honk speedfully and seasonably, how sphincteral is Carlyle? Be part of nature was thinking when they all things might go deeper into a declaration independence mod ever Volta Park, Md. We retain nothing else, norman lear declaration of independence mod may not visible to independence is norman. Declaration independence mod ever made for. What happens in a recession? Internet search engine Magellan. Declaration of Independence Full Size Reproduction National. Norman Lear the TV writer and producer who negotiate behind the 1970s. It held the longest running independent investigative organization in the country such an unblemished track record. Norman buys the Declaration of Independence And the legend of Joe E. American apartheid breaks down. Add this declaration independence mod ever changed american revolution is norman lear declaration of independence is norman lear produced by committee and its own. Library of Congress the original Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States which are main in some custody of shit Department. Norman Lear is a distinguished television and film producer as handsome as a. Norman lear and norman lear was a declaration of. How do you feel about the country today compared to the country you founded People for the American Way to help? I learned to love of Bill of Rights the Declaration of Independence and the. In each episode, who used to flip me a quarter. -

Starring a Film by Amy French

in association with NORMAN LEAR GEORGE LOPEZ present Starring Lupe Ontiveros • Danny Trejo • Spencer John French A Film by Amy French USA 2010 In English and Spanish Running Time: 90 minutes Stereo Sound Not Rated For images and downloads, visit www.elsuperstar.com PUBLICITY CONTACT DISTRIBUTOR CONTACT Beth Portello Richard Castro Cinema Libre Studio Cinema Libre Studio 8328 De Soto Avenue 8328 De Soto Avenue Canoga Park, CA 91304 Canoga Park, CA 91304 T: (818) 349-8822 T: (818) 349-8822 F: (818) 349-9922 F: (818) 349-9922 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Born Jonathan French in Beverly Hills, California and orphaned at 3 months, this young boy was adopted by his Mexican nanny, Nena (Lupe Ontiveros) and step-father, E.J. (Danny Trejo) and raised to be a good, God-fearing Mexican with a love for ranchero music. At age 33, in his “Jesus Year,” and now known as Juan Francés, his is a gardener, valet-parker, short- order cook, nanny and janitor by day, but has been blessed by the Virgin of Guadalupe with the talent to sing like the angels. He takes his ranchero act from the small, half-empty soccer bars in East L.A., to a larger music festival audience where he is discovered and quickly swept into Mexican pop stardom. Caught in the whirlwind of fame, Juan’s everyman appearance and musical style undergo a celebrity make-over. He changes his name to “El Guero” and his songs for the working-class are transformed into heartless Reggaeton. When the dark truth about Juan’s history is revealed to him, he must look at himself and ask: Will he choose the Mexican man in his heart or the bald pink guy he sees in the mirror? 2 www.ElSuperstar.com FESTIVALS & AWARDS “EXCEPTIONAL!” – Jenn Brown, fwix.com “…be ready for something quite original, different from possibly anything you have ever seen. -

Information Handout

The Image and Impact of Food in Entertainment Milano, Sept 4, 2015 Storytellers love food. Wanting it, growing it, preparing it, eating (or not eating) it: food has always been depicted in entertainment and the arts. Today we know from research that stories can have a significant impact on what people know, feel and do. For better and worse, food’s depictions in entertainment like movies, television and music can be models for behavior and beliefs. How do the images of food in entertainment affect us? What if storytellers chose to use their power to inspire audiences to make healthy food choices? NORMAN LEAR and starred in his first feature film for Sony Pictures.Exporting Ray- Known as the creator of Archie Bunker and mond, the true story about the attempt to turn Everybody Loves Ray- All in the Family, Lear’s television credits in- mond into a Russian sitcom, was met with critical acclaim. Rosenthal clude Sanford & Son; Maude; Good Times; will next combine his love of food and travel with his unique brand The Jeffersons; Mary Hartman, Mary Hart- of humor for I’ll Have What Phil’s Having, premiering on September man, and the dramatic series Palmerstown 28, 2015 on PBS. Rosenthal lives in Los Angeles, with his wife, actress U.S.A. His motion picture credits include Monica Horan (who played Amy on Everybody Loves Raymond), and Cold Turkey, Divorce American Style, Fried their two children. Green Tomatoes, Stand By Me and The Princess Bride. In 1999, U.S. President Bill Clinton bestowed the National Medal of Arts on Lear, SHERRY YARD noting that “Norman Lear has held up a mirror to American society For 30 years, renowned Chef Sherry Yard has and changed the way we look at it.” He has the distinction of being embraced a range of responsibilities from among the first seven television pioneers inducted into the Television creating savory and sweet menus, crafting Academy Hall of Fame (1984). -

AM Norman Lear Subject Bio FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMastersPBS American Masters – Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You Premieres nationwide Tuesday, October 25 at 9:00 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Norman Lear Biography Norman Lear has enjoyed a long career in television and film, and as a political and social activist and philanthropist. Lear began his television writing career in 1950 when he and his partner, Ed Simmons, were signed to write for The Ford Star Revue , starring Jack Haley. After only four shows, they were hired away by Jerry Lewis to write for him and Dean Martin on The Colgate Comedy Hour , where they worked until the end of 1953. They then spent two years on The Martha Raye Show , after which Lear worked on his own for The Tennessee Ernie Ford Show and The George Gobel Show . In 1958, Lear teamed with director Bud Yorkin to form Tandem Productions. Together they produced several feature films, with Lear taking on roles as executive producer, writer and director. He was nominated for an Academy Award in 1967 for his script for Divorce American Style. In 1970, CBS signed with Tandem to produce All in the Family , which first aired on January 12, 1971, and ran for nine seasons. It earned four Emmy Awards for Best Comedy series, as well as the Peabody Award in 1977. -

A Norman Lear Center Conference Annenberg Auditorium USC

A Norman Lear Center Conference Annenberg Auditorium USC Annenberg School for Communication January 29, 2005 2 THE NORMAN LEAR CENTER Ready to Share: Fashion & the Ownership of Creativity Ready to Share: Fashion & the Ownership of Creativity On January 29, 2005, The Norman Lear Center held a landmark event on fashion and the ownership of creativity. Ready to Share explored the fashion industry's enthusiastic embrace of sampling, appropriation and borrowed inspiration, core components of every creative process. Presented by the Lear Center's Creativity, Commerce & Culture project, and sponsored by The Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising/FIDM, this groundbreaking conference featured provocative trend forecasts, sleek fashion shows and an eclectic mix of experts from fashion, music, TV and film. Discussion sessions covered fashion and creativity; intellectual property law; fashion and entertainment; and the future of sharing. Participants Cate Adair, Costume Kevin Jones, Curator, The Laurie Racine, Senior Fellow, Designer for Desperate Fashion Institute of Design & The Norman Lear Center; Housewives (ABC) Merchandising Museum President, Center for the Public Domain Rose Apodaca, West Coast Martin Kaplan, Director, The Bureau Chief, Women's Wear Norman Lear Center; Sheryl Lee Ralph, Actress, Daily Associate Dean, USC singer, director, producer and Annenberg School for designer David Bollier, Senior Fellow, Communication The Norman Lear Center; Cameron Silver, President, Author, Brand Name Bullies Rick Karr, Television Decades, Inc., -

Downloads on Napster in the Late 1990S

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tell It Like It Is: Television and Social Change, 1960-1980 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3019m0d1 Author Flach, Kathryn L Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Tell It Like It Is: Television and Social Change, 1960-1980 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Kathryn L. Flach Committee in Charge: Professor Rebecca Jo Plant, Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Dayo F. Gore Professor David Serlin Professor Daniel Widener 2018 © Kathryn L. Flach, 2018. All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Kathryn L. Flach is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii DEDICATION For my family—Fred, Marylee, Ulices, and Emilio iv EPIGRAPH “It’s not what they said, it’s how they said it.” -Marie Petrucelli v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .................................................................................................................... iii Dedication .......................................................................................................................... iv Epigraph .............................................................................................................................. v Table of Contents .............................................................................................................. -

Bullying (1950 - 2010): the Bully and the Bullied

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2012 Bullying (1950 - 2010): The Bully and the Bullied Steven Arthur Provis Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Provis, Steven Arthur, "Bullying (1950 - 2010): The Bully and the Bullied" (2012). Dissertations. 381. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/381 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2012 Steven Arthur Provis LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO BULLYING (1950-2010): THE BULLY AND THE BULLIED A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION IN CANADACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION PROGRAM IN EDUCATIONAL ADMINISTRATION BY STEVEN ARTHUR PROVIS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2012 Copyright by Steven Arthur Provis, 2012 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dr. Janis Fine for her guidance and leadership. Your enthusiasm and passion for leading with your heart has impacted my life. I am forever grateful for your belief in me. Thanks also go to Dr. Marla Israel and Dr. Nicholas Polyak for serving as readers on my committee and providing guidance during the process. This dissertation and degree would not have been completed without the motivation and support of Dr.