A Norman Lear Center Conference Annenberg Auditorium USC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hervey-Grimes-Resume.Pdf

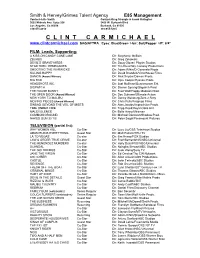

Smith & Hervey/Grimes Talent Agency E85 Management Contact-Julie Smith Contact-Greg Strangis & Jacob Gallagher 3002 Midvale Ave. Suite 206 3406 W. Burbank Blvd Los Angeles, Ca 90034 Burbank, Ca 91505 310-475-2010 310-955-5835 C L I N T C A R M I C H A E L www.clintcarmichael.com SAG/AFTRA Eyes: Blue/Green Hair: Salt/Pepper HT: 6’4” FILM: Leads, Supporting: A KISS ON CANDY CANE LANE Dir: Stephanie McBain ZBURBS Dir: Greg Zekowski DEVIL’S GRAVEYARDS Dir: Doug Glover/ Pilgrim Studios STAR TREK: RENEGADES Dir: Tim Russ/Sky Conway Productions SHOOTING THE WARWICKS Dir: Adam Rifkin/D-Generate Prods KILLING HAPPY Dir: David Brandvik/Victorhouse Films DAMON (Award Winner) Dir: Nick Snyder/Damon Prods. BIG BAD Dir: Opie Cooper/Eyevox Prods. HEADSHOTS INC. Dir: Joel Hoffman/Quarterwater Ent. DISPATCH Dir: Steven Sprung/Dispatch Prod. THE HOUSE BUNNY Dir: Fred Wolf/Happy Madison Prod. THE OPEN DOOR (Award Winner) Dir: Doc Duhame/Ultimate Action NEW YORK TO MALIBU Dir: Danny Weisberg/Zero 2 Sixty MOVING PIECES (Award Winner) Dir: Chris Pulis/Froglegs Films SINBAD: BEYOND THE VEIL OF MISTS Dir: Alan Jacobs/Improvision Prods. TIME UNDER FIRE Dir: Tripp Reed/Royal Oaks Ent. MALEVOLENCE Dir: Belle Avery/Miramax COMMON GROUND Dir: Michael Donovan/Shadow Prod. NAKED GUN 33 1/3 Dir: Peter Segal/Paramount Pictures TELEVISION (partial list): WHY WOMEN KILL Co-Star Dir: Lucy Liu/CBS Television Studios ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING Guest Star Dir: Matt Pollack/TRU TV LA TO VEGAS Co-star Dir: Jim Hensz/FOX Studios LAW & ORDER TRUE CRIME Co-star Dir: Fred -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: the Image of the Journalist As a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’S Sex and the City

Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: The Image of the Journalist as a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’s Sex and the City By Bibi Wardak Abstract New York Star sex columnist Carrie Bradshaw lives the life of a celebrity in HBO’s Sex and the City. She mingles with the New York City elite at extravagant parties, dates the city’s most influential men and enjoys the adoration of fans. But Bradshaw echoes the image of many female journalists in popular culture when it comes to romance. Bradshaw is thirty-something, unmarried and unsure about having children. Despite having a successful career and loyal friends, she feels unfulfilled after each failed romantic relationship. I. Introduction “A wildly successful career and a relationship -- I was afraid…women only get one or the other.”1 That’s a fear Carrie Bradshaw just can’t shake. The sex columnist for the New York Star is unmarried, career-oriented and unsure if she will ever have a traditional family.2 Just like other modern sob sisters, she is romantically unfulfilled and has sacrificed aspects of her personal life for professional success.3 Bradshaw, played by Sarah Jessica Parker in HBO’s hit television show Sex and the City, portrays a stereotypical image of female journalists found in television and film.4 She and other female journalists in the series struggle to balance a successful Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: The Image of the Journalist as a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’s Sex and the City By Bibi Wardak 2 career and satisfying romantic life. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

The 2009 Shift Index

Measuring the forces of long-term change The 2009 Shift Index Deloitte Center for the Edge John Hagel III, John Seely Brown, and Lang Davison Core Research Team Duleesha Kulasooriya Tamara Samoylova Brent Dance Mark Astrinos Dan Elbert Foreword A seemingly endless stream of books, articles, reports, applications, it may have more impact in how it changes and blogs make similar claims: The world is flattening; our conception of the economy. Interpreted through the the economy has picked up speed; computing power is lens of neoclassical economics, the Shift Index captures increasing; competition is intensifying. shifts in fundamentals, particularly on the cost side where technological changes allow firms to do more with less. Though we’re aware of these trends in the abstract, But, the Shift Index, by name alone, calls into question the we lack quantified measures. We know that a shift is neoclassical mindset that focuses on re-equilibration. underway, but we have no method of characterizing its speed or acceleration or making comparisons. Are The Shift Index resonates instead with a conceptual model rates of change increasing, decreasing, or settling into of the world economy based on complex dynamics. In stable patterns (e.g. Moore’s Law)? How do we compare this framework, the economy can be conceptualized as a exponential changes in bandwidth to linear increases complex adaptive system with diverse entities adaptively in Internet usage? Without times series data and a interacting to produce emergent patterns (and occasional methodology for integrating those data, we cannot large events). If one embraces the complex, dynamic identify, anticipate, or plan for change. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened. -

Real Men Can Dance, but Not in That Costume: Latter-Day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-03-17 Real Men Can Dance, But Not in That Costume: Latter-day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars Karson B. Denney Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Denney, Karson B., "Real Men Can Dance, But Not in That Costume: Latter-day Saints' Perception of Gender Roles Portrayed on Dancing with the Stars" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 2615. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2615 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REAL MEN CAN DANCE, BUT NOT IN THAT COSTUME: LATTER-DAY SAINTS‟ PERCEPTION OF GENDER ROLES PORTRAYED ON “DANCING WITH THE STARS” By Karson B. Denney A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communications Department of Communications Brigham Young University April 2011 Copyright © 2011 Karson B. Denney All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REAL MEN CAN DANCE, BUT NOT IN THAT COSTUME: LATTER-DAY SAINTS‟ PERCEPTION OF GENDER ROLES PORTRAYED ON “DANCING WITH THE STARS” Karson B. Denney Department of Communications Master of Arts This thesis attempts to better understand gender roles portrayed in the media. By using Stuart Hall‟s theory of audience reception (Hall, 1980) the researcher looks into dance and gender in the media to indicate whether or not LDS participants believe stereotypical gender roles are portrayed on “Dancing with the Stars.” Through four focus groups containing a total of 30 participants, the researcher analyzed costuming, choreography, and judges‟ comments through the viewer‟s eyes. -

Dr. Hamadoun I. Touré

This PDF is provided by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an officially produced electronic file. Ce PDF a été élaboré par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'une publication officielle sous forme électronique. Este documento PDF lo facilita el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un archivo electrónico producido oficialmente. ﺟﺮﻯ ﺇﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻲ ﻣﻠﻒ ﻣﻦ ﻣﺄﺧﻮﺫﺓ ﻭﻫﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ، ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ، (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻣﻦ ﻣﻘﺪﻣﺔ PDF ﺑﻨﺴﻖ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﺭﺳﻤﻴﺎ ً◌ ﺇﻋﺪﺍﺩﻩ 本PDF版本由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案服务室提供。来源为正式出版的电子文件。 Настоящий файл в формате PDF предоставлен библиотечно-архивной службой Международного союза электросвязи (МСЭ) на основе официально созданного электронного файла. © International Telecommunication Union N.° 6 Agosto de 2013 UNIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE TELECOMUNICACIONES itunews.itu.int Join us in Comunicaciones digitales y reglamentación Los organismos reguladores y la industria mundiales intercambian puntos de vista en Varsovia to continue the conversation that matters Nuevas aplicaciones, nuevas plataformas • Servicio universal • Polonia se pasa a la televisión digital • Innovación del espectro • La Internet de las Cosas… Facilitamos la gestión de sus Espacios en Blanco Le cuenta lo que ocurre en el mundo de las telecomunicaciones Cada vez que hace una llamada telefónica, utiliza un móvil, emplea el Correo-e, ve la televisión o © vario images GmbH & Co.KG/Alamy Philips accede a Internet, se está beneficiando de la labor que entraña Tomorrow´s Communications la misión de la UIT: Designed Today Conectar al mundo Stockxpert Fotosearch Soluciones informáticas y pericia para la Gestión y Control del Espectro y para la Si desea información para anunciarse, Anúnciese en Actualidades de la UIT Planificación e Ingeniería de Redes Radioeléctricas. -

Norman Norell

Norman Norell Autor(en): [s.n.] Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Textiles suisses [Édition multilingue] Band (Jahr): - (1968) Heft 5 PDF erstellt am: 30.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-796712 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Norman Norell was born in Noblesville, Indiana, and as a child his family moved to Indianapolis where he lived until he was 19. From early boyhood he yearned to be an artist and his education was directed toward that goal. He went to New York to study painting at the Parsons School and then graduated from the Pratt Institute. -

Phd Thesis. Loughborough University, 2014

Building blocks for the internet of things Citation for published version (APA): Stolikj, M. (2015). Building blocks for the internet of things. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2015 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. If the publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license above, please follow below link for the End User Agreement: www.tue.nl/taverne Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at: [email protected] providing details and we will investigate your claim.