Putting It on Ice: a Social History Op Hockey in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hockeycanada.Ca/CENTENNIALCUP Hockeycanada.Ca/COUPEDUCENTENAIRE

MARITIME HOCKEY LEAGUE LIGUE DE HOCKEY JUNIOR (MHL) AAA DU QUÉBEC (LHJAAAQ) MHL Amherst Ramblers Forts de Chambly MHL Campbellton Tigers L’Everest de la Côte-du-Sud 131 TEAMS, 10 LEAGUES | 131 ÉQUIPES, 10 LIGUES Edmundston Blizzard Flames de Gatineau MHL Fredericton Red Wings Inouk de Granby Grand Falls Rapids Collège Français de Longueuil Miramichi Timberwolves Rangers de Montréal-Est Pictou County Crushers Arctic de Montréal-Nord South Shore Lumberjacks Titan de Princeville MANITOBA JUNIOR HOCKEY SASKATCHEWAN JUNIOR Summerside Western Capitals Prédateurs de Saint-Gabriel-de-Brandon LEAGUE (MJHL) HOCKEY LEAGUE (SJHL) LHJAAAQ Truro Bearcats Panthères de Saint-Jérôme SJHL Valley Wildcats Cobras de Terrebonne LHJAAAQ Yarmouth Mariners Braves de Valleyfield Dauphin Kings Battlefords North Stars Shamrocks du West Island Neepawa Natives Estevan Bruins SJHL OCN Blizzard Flin Flon Bombers LHJAAAQ Portage Terriers Humboldt Broncos COUPE ANAVET CUP COUPE FRED PAGE CUP SJHL Selkirk Steelers Kindersley Klippers Steinbach Pistons La Ronge Ice Wolves Swan Valley Stampeders Melfort Mustangs CENTRAL CANADA HOCKEY LEAGUE (CCHL) Virden Oil Capitals Melville Millionaires WEST/OUEST EAST/EST Waywayseecappo Wolverines Nipawin Hawks Winkler Flyers Notre Dame Hounds CCHL Winnipeg Blues Weyburn Red Wings MJHL Brockville Braves Navan Grads Yorkton Terriers CCHL Carleton Place Canadians Nepean Raiders Cornwall Colts Ottawa Jr. Senators MJHL Hawkesbury Hawks Pembroke Lumber Kings CCHL Kanata Lasers Rockland Nationals Kemptville 73’s Smiths Falls Bears MJHL PANTHÈRES -

Special Report 10-02 Compendium of Long-Term Wildlife Monitoring

ncasi NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR AIR AND STREAM IMPROVEMENT COMPENDIUM OF LONG-TERM WILDLIFE MONITORING PROGRAMS IN CANADA SPECIAL REPORT NO. 10-02 OCTOBER 2010 by Sonya Lévesque Saguenay, Quebec Introduction by Darren Sleep, Ph.D. NCASI Montreal, Quebec Acknowledgments The author acknowledges the assistance of the various program managers across Canada, who were kind enough to take some of their time to answer questions and to review, comment upon, and edit project descriptions. A special thanks to Denis Lepage, from Bird Studies Canada, for his collaboration and interest. The author also thanks Darren Sleep and Kirsten Vice, from the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, for their trust and help. For more information about this research, contact: Darren J.H. Sleep, Ph.D. Kirsten Vice Senior Forest Ecologist Vice President, Canadian Operations NCASI NCASI P.O. Box 1036, Station B P.O. Box 1036, Station B Montreal, QC H3B 3K5 Canada Montreal, QC H3B 3K5 Canada (514) 286-9690 (514) 286-9111 [email protected] [email protected] For information about NCASI publications, contact: Publications Coordinator NCASI P.O. Box 13318 Research Triangle Park, NC 27709-3318 (919) 941-6400 [email protected] Cite this report as: National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. (NCASI). 2010. Compendium of long-term wildlife monitoring programs in Canada. Special Report No. 10-02. Research Triangle Park, N.C.: National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. © 2010 by the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, Inc. ncasi serving the environmental research needs of the forest products industry since 1943 PRESIDENT’S NOTE Wildlife monitoring can be a reliable source of information that contributes to effective forest management. -

Roderick and Magnus Flett: Stanley Cup Winners

Roderick and Magnus Flett: Stanley Cup Winners Rod Flett was on three Stanley Cup winning teams. The first cup was won by the Winnipeg Victorias in 1896. His younger brother Magnus Flett also played for the Win- nipeg Victorias when they won the Stanley Cup again in 1901 and 1902. Magnus Linklater Flett. (b. 1878) Metis hockey player Magnus Flett from Kildonan was born on September 1, 1878, the son of David Flett and Catherine McLeod. Both Magnus and his brother Roderick played for the 1901 and 1902 Stanley Cup champion Winnipeg Victorias. He played counter point position, now known as right defense. The brothers were good-sized men, Rod stood 6’ 3” and Magnus was 6’1’’. The 1896 and 1901 Winnipeg Victorias are inducted into the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame and the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame and Museum in the team category. Another Metis, Antoine Gingras also played with the 1901 and 1902 Victorias. Roderick McLeod Flett. (1873-1927) Metis hockey player Rod Flett from Kildonan was born on February 27, 1873, the son of David Flett and Catherine McLeod. Rod played for the first Manitoba team to win the Stanley cup, the 1896 Victorias. Both Roderick and his brother Magnus played for the 1901 and 1902 Stanley Cup champion Winnipeg Victorias. In 1896 they defeated the Montreal Victorias for the cup, in 1901 they defeated the Montreal Shamrocks and in 1902 they defeated the Toronto Wellingtons. Pre NHL the Stanley Cup was a challenge trophy where any cham- pionship team could challenge the current Stanley Cup champion. -

British Columbia Hockey League (Bchl)

MARITIME HOCKEY LIGUE DE HOCKEY 129 Teams 10 Leagues / 129 équipes 10 ligues LEAGUE (MHL) JUNIOR DU QUÉBEC (LHJQ) Amherst Ramblers Inouk de Granby Road to the Dieppe Commandos Campbellton Tigers Condors de Kahnawake Dieppe Commandos MHL Dieppe Commandos Maroons de Lachine Miramichi Timberwolves Collège Français de Longueuil MHL Truro Bearcats Pictou County Crushers Rangers de Montréal-Est 2015 RBC Cup South Shore Lumberjacks Titan de Princeville MHL St. Stephen County Aces Lauréats de Saint-Hyacinthe Summerside Western Capitals Panthères de Saint-Jérôme MANITOBA JUNIOR SASKATCHEWAN JUNIOR Truro Bearcats Arctic de Saint-Léonard HOCKEY LEAGUE (MJHL) HOCKEY LEAGUE (SJHL) Melfort Mustangs Parcours vers la Valley Wildcats Montagnards de Sainte-Agathe SJHL Woodstock Slammers Cougars de Sherbrooke Melfort Mustangs Collège Français de Longueuil Yarmouth Mariners Cobras de Terrebonne Dauphin Kings Battlefords North Stars Coupe RBC 2015 Braves de Valleyfield Collège Français de Longueuil LHJQ Neepawa Natives Estevan Bruins Notre Dame Hounds SJHL Mustangs de Vaudreuil-Dorion OCN Blizzard Flin Flon Bombers Coupe Western Canada Cup Coupe Fred Page Cup LHJQ Portage Terriers Humboldt Broncos SJHL Cougars de Sherbrooke Selkirk Steelers Kindersley Klippers Steinbach Pistons La Ronge Ice Wolves Penticton Vees Carleton Place Canadians LHJQ Swan Valley Stampeders Melfort Mustangs CENTRAL CANADA HOCKEY LEAGUE (CCHL) Virden Oil Capitals Melville Millionaires West/Ouest #1 East/Est Carleton Place Canadians Waywayseecappo Wolverines Nipawin Hawks Portage Terriers Winkler Flyers Notre Dame Hounds Carleton Place Canadians CCHL Brockville Braves Kanata Lasers Winnipeg Blues Weyburn Red Wings MJHL Portage Terriers Yorkton Terriers Carleton Place Canadians Kemptville 73’s CCHL Pembroke Lumber Kings Cornwall Colts Nepean Raiders Steinbach Pistons MJHL Cumberland Grads Ottawa Jr. -

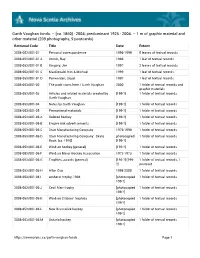

Garth Vaughan Fonds. – [Ca

Garth Vaughan fonds. – [ca. 1860] - 2004; predominant 1925 - 2004. – 1 m of graphic material and other material (209 photographs, 9 postcards) Retrieval Code Title Date Extent 2008-053/001-01 Personal correspondence 1996-1999 5 leaves of textual records 2008-053/001-01 A Cronin, Ray 1996 1 leaf of textual records 2008-053/001-01 B Gregory, Jim 1997 2 leaves of textual records 2008-053/001-01 C MacDonald, Kim & Michael 1999 1 leaf of textual records 2008-053/001-01 D Penwarden, Lloyd 1997 1 leaf of textual records 2008-053/001-02 The puck starts here / Garth Vaughan 2000 1 folder of textual records and graphic materials 2008-053/001-03 Articles and related materials created by [199-?] 1 folder of textual records Garth Vaughan 2008-053/001-04 Notes by Garth Vaughan [199-?] 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-05 Promotional materials [199-?] 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 A Colored hockey [199-?] 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 B Empire rink advertisements [199-?] 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 C Starr Manufacturing Company 1976-1998 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 D Starr Manufacturing Company: Skate photocopied 1 folder of textual records Book, [ca. 1910] [199-?] 2008-053/001-06 E Windsor hockey (general) [199-?] 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 F Windsor Minor Hockey Association 1972-1973 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 G Trophies, awards (general) [192-?]-[199- 1 folder of textual records, 1 ?] postcard 2008-053/001-06 H Allan Cup 1998-2000 1 folder of textual records 2008-053/001-06 I Amherst trophy, 1904 [photocopied 1 folder of textual records 199-?] 2008-053/001-06 J Cecil Marr trophy [photocopied 1 folder of textual records 199-?] 2008-053/001-06 K Windsor Citizens' trophies [photocopied 1 folder of textual records 199-?] 2008-053/001-06 L New Brunswick hockey [photocopied 1 folder of textual records 199-?] 2008-053/001-06 M Ontario hockey [photocopied 1 folder of textual records 199-?] https://memoryns.ca/garth-vaughan-fonds Page 1 Garth Vaughan fonds. -

Proquest Dissertations

"The House of the Irish": Irishness, History, and Memory in Griffintown, Montreal, 1868-2009 John Matthew Barlow A Thesis In the Department of History Present in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada March 2009 © John Matthew Barlow, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63386-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63386-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre im primes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-Learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By

A Lesson in Stone: Examining Patterns of Lithic Resource Use and Craft-learning in the Minas Basin Region of Nova Scotia By © Catherine L. Jalbert A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies for partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2011 St. John’s Newfoundland Abstract Examining the Late Woodland (1500-450 BP) quarry/workshop site of Davidson Cove, located in the Minas Basin region of Nova Scotia, a sample of debitage and a collection of stone implements appear to provide correlates of the novice and raw material production practices. Many researchers have hypothesized that lithic materials discovered at multiple sites within the region originated from the outcrop at Davidson Cove, however little information is available on lithic sourcing of the Minas Basin cherts. Considering the lack of archaeological knowledge concerning lithic procurement and production, patterns of resource use among the prehistoric indigenous populations in this region of Nova Scotia are established through the analysis of existing collections. By analysing the lithic materials quarried and initially reduced at the quarry/workshop with other contemporaneous assemblages from the region, an interpretation of craft-learning can be situated in the overall technological organization and subsistence strategy for the study area. ii Acknowledgements It is a pleasure to thank all those who made this thesis achievable. First and foremost, this thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and support provided by my supervisor, Dr. Michael Deal. His insight throughout the entire thesis process was invaluable. I would also like to thank Dr. -

April 2, 2021 Vs Cape Breton Eagles

GAME PREVIEW Happy Easter! This afternoon’s Good Friday matchup features your Halifax Mooseheads (13-16-5-3) vs the visiting Cape Breton Eagles (12-22-1-0) at 4pm at Scotiabank Centre. The Moose are looking for a bounce back game after a one-sided loss last night to Charlottetown that saw the Islanders not only win 6-2 but dominate on the shot clock 45-15. Halifax played that game with a depleted lineup as Senna Peeters, Cam Whynot, Kyle Petten and leading scorer Elliot Desnoyers all sat out as a precaution with virus symptoms. All players have tested negative for Covid-19. All four players will be game-time decisions this afternoon. Defenceman Jake Furlong was injured when he took a puck to the face last night and will miss today’s game. Fans not in attendance can watch on Eastlink channels 10 or 610, listen on NEWS 957 or subscribe to the QMJHL webcast at https://qmjhl.neulion.com/qmjhl/. SCOTTY’S 3 WHOPPERS OF THE GAME MORE OF THE SAME The QMJHL announced four additional games in April for the Mooseheads yesterday, all of them against Charlottetown. The Herd will play two on the road and twice at home (April 9th & 17th) while there is strong indications that play will be opened up to facing the New Brunswick teams as the regular season wraps up and the playoffs begin. That will be a welcome sight for all of us. Q DEBUT X2 Dylan Chisholm was signed and called up on an emergency basis last night to fill in on the blue line. -

The Problem of Out-Migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871-1921: a New Look Patricia A

Document generated on 09/24/2021 3:29 p.m. Acadiensis The Problem of Out-Migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871-1921: A New Look Patricia A. Thornton Volume 15, Number 1, Autumn 1985 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad15_1art01 See table of contents Publisher(s) The Department of History of the University of New Brunswick ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Thornton, P. A. (1985). The Problem of Out-Migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871-1921:: A New Look. Acadiensis, 15(1), 3–34. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 1985 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ PATRICIA A. THORNTON The Problem of Out-Migration from Atlantic Canada, 1871-1921: A New Look THE PERIOD FROM THE 1860S TO THE 1920s was a crucial one for Atlantic Can ada. During this period both the Maritimes and Newfoundland failed to develop successfully. The Maritimes, despite optimistic beginnings, were ultimately un able to complete their industrial transformation. Newfoundland was unable to diversify out of its single-resource base, which in turn never modernized suf ficiently to compete with "newer" fishing nations. -

Regional Climate Quarterly

Quarterly Climate Impacts Gulf of Maine Region and Outlook December 2019 Gulf of Maine Significant Events –September –November 2019 September Hurricane Dorian affected the region from September 6 to 8. The storm passed off the In early September, the Maritimes New England coast then transitioned into a post-tropical storm (with hurricane-force winds) experienced extreme as it approached the Maritimes. It made landfall near Halifax, N.S., then moved across impacts from post-tropical P.E.I. and into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Dorian had a major impact on the Maritimes due storm Dorian. to intense rainfall, extreme winds, and storm surge. See Regional Impacts for details. A rapidly intensifying storm set On September 18, temperatures as low as -2.8°C (27°F) set daily records and brought pressure records and produced the first frost to some New Brunswick and Maine sites. A few days later, on September 22 damaging winds in New and 23, some areas experienced daily record high temperatures of up to 32°C (89°F). England in mid-October. October A coastal storm, which strengthened into Tropical Storm Melissa, stalled off the Northeast U.S. coast then moved south of Nova Scotia from October 9 to 13. The storm brought rough surf, up to 90 mm (3.50 in.) of rain, and damaging wind gusts of up to 97 km/h (60 mph) to eastern Massachusetts and the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia. A rapidly intensifying storm moved through the region from October 16 to 18. New lowest sea level pressure records for October were set at Boston, MA, Concord, NH, and Portland, ME. -

Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson

This article was downloaded by: [Canadian Research Knowledge Network] On: 9 September 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 783016864] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of the History of Sport Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713672545 Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War JJ Wilson To cite this Article Wilson, JJ(2005) 'Skating to Armageddon: Canada, Hockey and the First World War', International Journal of the History of Sport, 22: 3, 315 — 343 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09523360500048746 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360500048746 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

ANNUAL PROGRAM 2020 – 2021 Contents 2020

Honouring Excellence ANNUAL PROGRAM 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 2020 CEO Message / Chairs of the Hall of Fame / Board of Directors ....................... 2 Our Mission / Our Vision / Staff ............................................................................. 3 Our Museum Activities .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Our Education Program......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Communications ..................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Trivia ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Hall of Fame Selection Panel & Committee / Induction Update ...................................................................................... 8 Meet the Inductee Class of 2021............................................................................................................................................ 9 Hall of Fame Inductees List ................................................................................................................................................... 10 Friends of the Hall ..................................................................................................................................................................