The Opera: a Brief Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865)

1/3 Data Livret de Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865) Langue : Italien Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres musicales Date : 1813 Note : "Dramma serio" en 2 actes créé à Milan, Teatro alla Scala, le 26 décembre 1813. - Livret de Felice Romani d'après "Zenobia di Palmira" d'Anfossi Éditions de Aureliano in Palmira (19 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Partitions (13) Cavatina del maestro , Gioachino Rossini Quartetto pastorale , Gioachino Rossini Rossini nell' Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini nell'Aureliano in Palmira. (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Composto dal maestro , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et accompagnement de piano] Aureliano in Palmira, opéra , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini in due atti, musica di (1792-1868), Paris : Palmira, musica del (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini [Partition chant et Schonenberger , [s.d.] maestro Rossini. [Chant et , [s.d.] piano] piano] Terzettino nel Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Aureliano in Palmira. Mille sospiri e lagrimé. - [7] Aureliano in Palmira , Felice Romani (2019) (1788-1865), Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Pesaro : Fondazione Rossini data.bnf.fr 2/3 Data Aureliano in Palmira, opera , Felice Romani Mille sospiri e Lagrime. Air , Gioachino Rossini in 2 atti (1788-1865), Gioachino à 2 v. tiré d'Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : [s.n.] , (1855) Rossini (1792-1868), Paris Palmira 1823 : Schonenberger , [1855] (1823) Ecco mi, ingiustinumi. -

Signumclassics

170booklet 6/8/09 15:21 Page 1 ALSO AVAILABLE on signumclassics Spanish Heroines Silvia Tro Santafé Orquesta Sinfónica de Navarra Julian Reynolds conductor SIGCD152 Since her American debut in the early nineties, Silvia Tro Santafé has become one of the most sought after coloratura mezzos of her generation. On this disc we hear the proof of her operatic talents, performing some of the greatest and most passionate arias of any operatic mezzo soprano. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 170booklet 6/8/09 15:21 Page 3 Rossini Mezzo Rossini Mezzo gratitude, the composer wrote starring roles for her in five of his early operas, all but one of them If it were not for the operas of Gioachino Rossini, comedies. The first was the wickedly funny Cavatina (Isabella e Coro, L’Italiana in Algeri) the repertory for the mezzo soprano would be far L’equivoco stravagante premiered in Bologna in 1. Cruda sorte! Amor tiranno! [4.26] less interesting. Opera is often thought of as 1811. Its libretto really reverses the definition of following generic lines and the basic opera plot opera quotes above. In this opera, the tenor stops Coro, Recitativo e Rondò (Isabella, L’Italiana in Algeri) has been described as “the tenor wants to marry the baritone from marrying the mezzo and does it 2. Pronti abbiamo e ferri e mani (Coro), Amici, in ogni evento ... (Isabella) [2.45] the soprano and bass tries to stop them”. by telling him that she is a castrato singer in drag. -

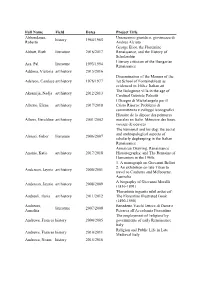

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Roberto History 1964

Full Name Field Dates Project Title Abbondanza, Umanesimo giuridico, giovinezza di history 1964/1965 Roberto Andrea Alciato George Eliot, the Florentine Abbott, Ruth literature 2016/2017 Renaissance, and the History of Scholarship Literary criticism of the Hungarian Acs, Pal literature 1993/1994 Renaissance Addona, Victoria art history 2015/2016 Dissemination of the Manner of the Adelson, Candace art history 1976/1977 1st School of Fontainebleau as evidenced in 16th-c Italian art The Bolognese villa in the age of Aksamija, Nadja art history 2012/2013 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti I Disegni di Michelangelo per il Alberio, Elena art history 2017/2018 Cristo Risorto: Problemi di committenza e sviluppi iconografici Histoire de la dépose des peintures Albers, Geraldine art history 2001/2002 murales en Italie. Mémoire des lieux, voyage de oeuvres The humanist and his dog: the social and anthropological aspects of Almasi, Gabor literature 2006/2007 scholarly dogkeeping in the Italian Renaissance American Drawing, Renaissance Anania, Katie art history 2017/2018 Historiography, and The Remains of Humanism in the 1960s 1. A monograph on Giovanni Bellini 2. An exhibition on late Titian to Anderson, Jaynie art history 2000/2001 travel to Canberra and Melbourne, Australia A biography of Giovanni Morelli Anderson, Jaynie art history 2008/2009 (1816-1891) 'Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est': Andreoli, Ilaria art history 2011/2012 The Florentine Illustrated Book (1490-1550) Andreoni, Benedetto Varchi lettore di Dante e literature 2007/2008 Annalisa Petrarca all'Accademia Fiorentina The employment of 'religiosi' by Andrews, Frances history 2004/2005 governments of early Renaissance Italy Religion and Public Life in Late Andrews, Frances history 2010/2011 Medieval Italy Andrews, Noam history 2015/2016 Full Name Field Dates Project Title Genoese Galata. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868)

4 CDs 4 Christian Benda Christian Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Sinfonia Prague COMPLETE OVERTURES COMPLETE ROSSINI GIOACHINO COMPLETE OVERTURES ROSSINI GIOACHINO 4 CDs 4 GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792–1868) COMPLETE OVERTURES Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Christian Benda Rossini’s musical wit and zest for comic characterisation have enriched the operatic repertoire immeasurably, and his overtures distil these qualities into works of colourful orchestration, bravura and charm. From his most popular, such as La scala di seta (The Silken Ladder) and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie), to the rarity Matilde of Shabran, the full force of Rossini’s dramatic power is revealed in these masterpieces of invention. Each of the four discs in this set has received outstanding international acclaim, with Volume 2 described as “an unalloyed winner” by ClassicsToday, and the Prague Sinfonia Orchestra’s playing described as “stunning” by American Record Guide (Volume 3). COMPLETE OVERTURES • 1 (8.570933) La gazza ladra • Semiramide • Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra (Il barbiere di Siviglia) • Otello • Le siège de Corinthe • Sinfonia in D ‘al Conventello’ • Ermione COMPLETE OVERTURES • 2 (8.570934) Guillaume Tell • Eduardo e Cristina • L’inganno felice • La scala di seta • Demetrio e Polibio • Il Signor Bruschino • Sinfonia di Bologna • Sigismondo COMPLETE OVERTURES • 3 (8.570935) Maometto II (1822 Venice version) • L’Italiana in Algeri • La Cenerentola • Grand’overtura ‘obbligata a contrabbasso’ • Matilde di Shabran, ossia Bellezza, e cuor di ferro • La cambiale di matrimonio • Tancredi CD 4 COMPLETE OVERTURES • 4 (8.572735) Il barbiere di Siviglia • Il Turco in Italia • Sinfonia in E flat major • Ricciardo e Zoraide • Torvaldo e Dorliska • Armida • Le Comte Ory • Bianca e Falliero 8.504048 Booklet Notes in English • Made in Germany ℗ 2013, 2014, 2015 © 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Maria Teresa Grassi

M.T. Grassi, Zenobia, un mito assente, “LANX” 7 (2010), pp. 299-314 Maria Teresa Grassi Zenobia, un mito assente Tra i grandi personaggi femminili della storia romana vanno senza dubbio annoverate due regine straniere, l’egiziana Cleopatra e la siriana Zenobia: entrambe hanno avuto un ruolo di primo piano nelle vicende politiche della loro epoca, ma la fama della prima - una vera star dell’immaginario collettivo - non è neppure paragonabile a quella della seconda.1 La vicenda di Zenobia si svolge nel III secolo d.C., in soli cinque anni, tra il 267 e il 272 d.C., nel settore orientale dell’Impero Romano, ed ha come epicentro la Siria e Palmira, importante città carovaniera posta in un’oasi del deserto siriano, a mezza strada tra l’Eufrate e il Mediterraneo. Di Zenobia abbiamo solo poche immagini, “sfuocate”, dalle monete coniate a suo nome (monete peraltro di grande importanza per ricostruire l’ascesa politica della regina) e nella stessa Palmira ben poco si può ricondurre a Zenobia (qualche grande complesso è stato talora definito come il “palazzo di Zenobia”, ma si tratta di attribuzioni di fantasia2) e scarse sono anche le fonti letterarie ed epigrafiche da cui ricavare qualche dato. Dal punto di vista romanzesco, Zenobia è indubbiamente poco attraente: al contrario di Cleopatra non se ne conoscono gli amori e neppure le circostanze della morte, non ha avuto intorno a sé personaggi di primo piano come Giulio Cesare, Marco Antonio e Augusto. Il suo antagonista, l’imperatore Aureliano, non ha la stessa fama: malgrado le indubbie qualità politiche e militari, è uno dei tanti imperatori del turbolento III secolo d.C. -

Rossini: La Recepción De Su Obra En España

EMILIO CASARES RODICIO Rossini: la recepción de su obra en España Rossini es una figura central en el siglo XIX español. La entrada de su obra a través de los teatros de Barcelona y Madrid se produce a partir de 1815 y trajo como consecuencia su presen- cia en salones y cafés por medio de reducciones para canto de sus obras. Más importante aún es la asunción de la producción rossiniana corno símbolo de la nueva creación lírica europea y, por ello, agitadora del conservador pensamiento musical español; Rossini tuvo una influencia decisi- va en la producción lírica y religiosa de nuestro país, cuyo mejor ejemplo serían las primeras ópe- ras de Ramón Carnicer. Rossini correspondió a este fervor y se rodeó de numerosos españoles, comenzando por su esposa Isabel Colbrand, o el gran tenor y compositor Manuel García, termi- nando por su mecenas y amigo, el banquero sevillano Alejandro Aguado. Rossini is a key figure in nineteenth-century Spain. His output first entered Spain via the theatres of Barcelona and Madrid in 1815 and was subsequently present in salons and cafés in the form of vocal reduc- tions. Even more important is the championing of Rossini's output as a model for modern European stage music which slwok up conservative Spanish musical thought. Rossini liad a decisive influence on die sacred and stage-music genres in Spain, the best example of which are Ramón Carnicer's early operas. Rossini rec- ipricated this fervour and surrounded himself with numerous Spanish musicians, first and foremost, his wife Isabel Colbrand, as well as die great tenor and composer Manuel García and bis patron and friend, the Sevil- lan banker Alejandro Aguado. -

˚Iuiû€Û”Ëúiå ¨?¹˛XX¸

660203-04 bk Ciro US 12/12/06 11:09 Page 12 Antonino Fogliani 2 CDs Born in 1976, Antonino Fogliani made an early start in his international career as a conductor. He studied piano and ROSSINI composition in Bologna and conducting at the Verdi Conservatorio in Milan. He not only attended master-classes with Gianluigi Gelmetti, but worked with him in productions at major opera-houses in Rome, Venice, Turin, London and Munich. He also worked with Alberto Zedda at the Accademia Rossiniana in Pesaro. Guest Ciro in Babilonia engagements have taken him to Milan, Bologna, Siena, Sofia, La Coruña, Parma, Sydney and Santiago de Chile. In his own country he has won a number of prizes, including, in 2000, at the Accademia Chigiana and in 2001 in San Remo the Premio Martinuzzi for young conductors. He has conducted Rossini’s Le Comte Ory in Paris, Donizetti’s Gemmabella • Islam-Ali-Zade • Botta Don Pasquale in Rome, Ugo, Conte di Parigi at the Donizetti Festival in Bergamo and at La Scala, and Lucia di Lammermoor. Other engagements have taken him to Liège and Naples, in addition to performances in Asia. He has Gierlach • Soulis • Trucco • ARS Brunensis Chamber Choir conducted several times at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro and for Rossini in Wildbad he has conducted and recorded L’occasione fa il ladro and Mosè in Egitto. Württemberg Philharmonic Orchestra ARS Brunensis Chamber Choir Antonino Fogliani The ARS Brunensis Chamber Choir was founded in Brno in 1979 and since then has participated in many international competitions, winning, among other successes, the IFAS in Pardubice in 1998. -

JOS-075-1-2018-007 Child Prodigy

From the Bel Canto Stage to Reality TV: A Musicological View of Opera’s Child Prodigy Problem Peter Mondelli very few months, a young singer, usually a young woman, takes the stage in front of network TV cameras and sings. Sometimes she sings Puccini, sometimes Rossini, rarely Verdi or Wagner. She receives praise from some well meaning but uninformed adult Ejudge, and then the social media frenzy begins. Aunts and uncles start sharing videos, leaving comments about how talented this young woman is. A torrent of blog posts and articles follow shortly thereafter. The most optimistic say that we in the opera world should use this publicity as a means to an end, to show the world at large what real opera is—without ever explaining how. Peter Mondelli The sentiment that seems to prevail, though, is that this performance does not count. This is not real opera. Opera was never meant to be sung by such a voice, at such an age, and under such conditions. Two years ago, Laura Bretan’s performance of Puccini’s “Nessun dorma” on America’s Got Talent evoked the usual responses.1 Claudia Friedlander responded admirably, explaining that there are basic physiological facts that keep operatic child prodigies at a distance from vocally mature singers.2 More common, however, are poorly researched posts like the one on the “Prosporo” blog run by The Economist.3 Dubious claims abound—Jenny Lind, for exam- ple, hardly retired from singing as the post claims at age twenty-nine, the year before P. T. Barnum invited her to tour North America. -

Rossini, G.: Aureliano in Palmira 8.660448-50

Rossini, G.: Aureliano in Palmira 8.660448-50 https://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=8.660448-50 Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) Aureliano in Palmira Dramma serio per musica in due atti Libretto di Felice Romani Prima rappresentazione: Milano, Teatro alla Scala, 26 dicembre 1813 Revised version by Ian Schofield, Edition Peters, London Aureliano: ................................................................ Juan Francisco Gatell Zenobia: ...................................................................... Silvia Dalla Benetta Arsace: ...................................................................................Marina Viotti Publia: ............................................................................. Ana Victória Pitts Orsape: ........................................................................................ Xiang Xu Licinio: ................................................................................. Zhiyuan Chen Gran sacerdote: .................................................... Baurzhan Anderzhanov Un pastore: ................................................................................ Un corista La scena è in Palmira e nelle vicinanze. CD 1 Coro di guerrieri Invoca te la supplice guerriera gioventù. [1] Sinfonia Coro di vergini, di guerrieri, di sacerdoti Salvi il tremante popolo l’eterna tua virtù. ATTO PRIMO Madre di questo regno, accorda a noi sostegno, il tuo tremante popolo Gran tempio d’Iside con simulacro a destra. salva da tanto orror. Gran sacerdote (spaventato) [2] N. 1 Introduzione -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today.