Educational Modules for the Critical Care Communication (C3) Course - a Communication Skills Training Program for Intensive Care Fellows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RIDDLE and MYSTERY a Tapestry of Faith Program for Children 6Th Grade

RIDDLE AND MYSTERY A Tapestry of Faith Program for Children 6th Grade BY RICHARD S. KIMBALL © Copyright 2010 Unitarian Universalist Association. This program and additional resources are available on the UUA.org web site at www.uua.org/re/tapestry 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHORS ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 THE PROGRAM ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 SESSION 1: THE BIG QUESTIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 SESSION 2: RELIGION TO THE RESCUE .......................................................................................................................................... 35 SESSION 3: LOOKING TOWARD TOMORROW ............................................................................................................................... 54 SESSION 4: THINKING OF GOD ......................................................................................................................................................... 74 SESSION -

Proceedings and Index of the 68Th Annual Convention

Proceedings and Index of the 68th Annual Convention Communications Workers of America Las Vegas Hilton Hotel Las Vegas, Nevada July 10-11, 2006 MONDAY MORNING SESSION July 10, 2006 The Opening Session of the Sixty-Eighth Annual Convention of the Communications Workers of America, held in the Conrad Ballroom of the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel and Casino, Las Vegas, Nevada, July 10-11, 2006, convened at 9:00 a.m., Louie Rocha, President, CWA Local 9423, Chair of the Northern California/Nevada Council, Temporary Chair, presiding. TEMPORARY CHAIR ROCHA: Good Morning! Buenos dias! We have a very full agenda this morning, so I ask all of you to take your seats. Will all of the delegates please take their seats. The official clock of the Northern California Council indicates that it is now 9:00 a.m. I would ask that everyone please be seated as I call the 68th Annual Convention of the Communications Workers of America to order. We have a busy schedule this morning and a very full two-day schedule, so would everyone please be seated so we can begin. I am Louie Rocha, President of the Northern California and Nevada Council and President of CWA Local 9423. Today I have the honor of serving as the Temporary Chair. On behalf of the officers and members of District 9, welcome to Las Vegas and the 68th Annual Convention of the Communications Workers of America. (Applause) As is our custom, we will open our Convention with a prayer. For the invocation, I would like to call upon Reverend Peter Romeo, Judicial Vicar of the Diocese of Las Vegas, Nevada. -

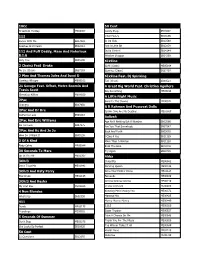

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

1 HUMMINGBIRD's GAZE Seth Heim Prof. Perritt: Law of Nation-Building Seminar Spring 2014 "Since the Revolution, Every

HUMMINGBIRD’S GAZE Seth Heim Prof. Perritt: Law of Nation-Building Seminar Spring 2014 "Since the revolution, every average Libyan hoped things would get better, but instead everything is worse," Mr. Jathran said, in his sleek, leather-chair- lined conference room in Ajdabiya's only hotel, where he served his guests cappuccinos. "We are sliding to a place like Afghanistan or Somalia," he said.1 I “I don’t know, Hamoud. Have you asked mother about this?” “Of course not. I know she’d forbid it. Probably send me down south to work on a dirt farm or hawk rugs to tourists near the border. After she’s chased me down the street, screaming to father’s ghost about how terrible I am.” “Ha, yeah, well,… she’s got a point.” Idriss’ voice over the phone was coming from behind a smile his brother could almost see, but suggestive with warning. “This is serious stuff. You know that, right? Hamoud, these defense forces aren’t a club. It’s no joke. These guys carry guns. Are you really ready to shoot someone? Over oil? Over tribal pride?” The phone conversation wasn’t going as Hamoud hoped it would. He hadn’t spoken to his brother Idriss in over a month, and only a few times this year. At 21, Idriss was nearly five years older than Hamoud, but much had happened in the past three years that made the age gap a chasm. Idriss fought in the partisan militia along with their tribe, and along with their father, to push Qadhaffi’s soldiers out of Ajdabiyah when the revolution swept across northeastern Libya in 2011. -

FILTERSCAN-Installation.Pdf

FILTERSCAN ® Reference Guide Version 3.02 The information contained herein is proprietary and is not to be used for purposes other than as an aid in the operation and/or maintenance of the of the product described herein and is not to be released or reproduced by anyone without the written permission of CleanAlert, LLC. Due to CleanAlert's constant strive for product improvement, minor discrepancies between the actual product, text and illustrations may exist. All information contained herein is based on the latest specifications at the time of publication and is subject to change without notice. FILTERSCAN ® is a registered trademark of CleanAlert, LLC. Contents Introduction ………………..…………………….………………………………………………………… 1 In The Box ..............................…………………………………………………………………………. 1 Tools Required ............…………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Safety ………………….…………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Application ………….……………………………............................................................................. 1 FCC Compliance ……………..………………………………………………………………………….. 2 IC Compliance ………………..………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Monitor Installation …………………..…………………….. ……………………………………. 2 Receiver Installation ……………..………………………….. ……………………………………. 6 Operation …………………..……………….……………………………………………………………….. 7 System Monitoring ……….……………………………………………………………….…………….. 7 Alarm Modes ………..………………..………………………….……………………………………… 7 Clogged Air Filter …………...……….………………………………………………………………….. 8 Low battery ………………..…………………………..…………………………………………………. 8 Malfunction ……………..………………………………………………………………………..………. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Deciding to Follow Your Heart Matthew 4:18-22

Deciding to Follow Your Heart Matthew 4:18-22 As Jesus was walking beside the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers: Simon called Peter, and his brother Andrew. They were casting a net into the lake, for they were fishermen. “Come, follow me,” Jesus said, “and I will send you out to fish for people.” At once they left their nets and followed him. Going on from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John. They were in a boat with their father Zebedee, preparing their nets. Jesus called them, and immediately they left the boat and their father and followed him. As many of you may know, Bill and Joy Powell are our traveling buddies. We’ve been from one end of the world to the other with them and have a collection of stories about our experiences – some we can tell and others we dare not make public. As you might imagine, traveling with Joy Powell is always an adventure. Joy is so personable and social she rarely meets a stranger. So I guess we shouldn’t have been surprised that day in Istanbul when we went to see The Blue Mosque. It was about 11:30 in the morning when we got to the Blue Mosque and as we made our way to the door, we were disappointed to discover we had 2 arrived during the time of prayer; and so a stern Arab man, who was posted at the door, told us we would have to come back later. -

June 2021 Newsletter

Volume 25 Issue 6 REMOVE THE MASK By Pastor Dennis Felder June 2021 Not certain if you are or were a fan of Batman. Batman disguises his true identity by wearing a mask. Behind the mask, Batman is a wealthy millionaire by the name of Bruce Wayne. Whenever a threat would arise, Bruce Wayne would slip into the bat cave; put on his bat costume and mask to conceal his true identity as he heroically fought the villains of Gotham City. Each time the villains placed Batman in a precarious position, they tried to remove his mask to reveal his true identity. During this pandemic, we too have been donning masks to fight an evil villain named COVID. COVID was and still is a ruthless disease, but we are about to eradicate its power with proper hygiene, medical advancement, and mask wearing. Slowly but surely, we are not only raising our hands in victory, but slowly and surely, we can lower our masks. When our masks are pulled down, we can see the real person. We can see one’s radiant smile or a frown of displeasure. Although needed at the time, masks did conceal one’s real identity. Masks often hide the true emotions of what a person is really feeling. Now that masks are being removed, how will others see you? In life, there are many masks that people wear that are not made of cloth. They are inward masks that will hide one’s true emotions, deep thoughts, and genuine feelings. These masks are frequently put on so that others cannot see the “real you”. -

Accumix™ a M 1 0 0 0 S O P E R a T O R M a N U a L

AccuMix™ A M 1 0 0 0 S O p e r a t o r M a n u a l E16204_B AccuMix™ 1000S Self Propelled Vertical Feed Mixer Operator Manual Highline Manufacturing HWY #27, P.O. Box 307 Vonda, SK S0K 4N0 Canada Phone: 306.258.2233 Fax: 306.258.2010 Toll Free: 1.800.665.2010 E16204_B Printed in Canada Copyright © 2020 by Highline Manufacturing All rights reserved. The content of this manual was based on the most current information available as of the date of copyright. It is the policy of Highline Manufacturing to improve and develop our products continually. We reserve the right to make changes or add improvements, at any time, without incurring any obligation to make changes or improvements on machines previously sold. Changes may not be reflected in this manual. Highline Manufacturing AccuMix 1000S Highline Team Message Congratulations on your purchase of the AccuMix 1000S manufactured by Highline Manufacturing. We are excited about you feeding with the technically advanced feed mixer that is self- propelled self loading.. You will find flexibility and maneuverability of operation with this product. This Operator Manual has been prepared to provide information necessary for the safe and efficient operation of your AccuMix 1000S. In the manual you will find safety procedures, maintenance routines and detailed operational instructions. If you find that you require information not covered in this manual, please feel free to consult your local dealer. Your dealer is always able to contact Highline for this technical information. Highline Manufacturing thanks and congratulates you for selecting the AccuMix 1000S as your machine of choice. -

Model 3124 ADSL2+ Ipdslam User Manual

Model 3124 ADSL2+ IpDSLAM User Manual Important This is a Class A device and is not intended for use in a residential environment. Sales Office: +1 (301) 975-1000 Technical Support: +1 (301) 975-1007 E-mail: [email protected] WWW: www.patton.com Part Number: 07M3124, Rev. A Revised: March 16, 2012 Patton Electronics Company, Inc. 7622 Rickenbacker Drive Gaithersburg, MD 20879 USA tel: +1 (301) 975-1000 fax: +1 (301) 869-9293 support: +1 (301) 975-1007 web: www.patton.com e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2012, Patton Electronics Company. All rights reserved. The information in this document is subject to change without notice. Patton Electronics assumes no liability for errors that may appear in this document. The software described in this document is furnished under a license and may be used or copied only in accordance with the terms of such license. Summary Table of Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Hardware Installation.................................................................................................................................... 11 3 Configuration................................................................................................................................................ 19 4 Operation and Maintenance.......................................................................................................................... 42 5 Troubleshooting........................................................................................................................................... -

Appliance Manager Operator's Guide

Silver Peak Appliance Manager Operator’s Guide VXOA 8.0 May 2016 PN 200030-001 Rev Q Silver Peak Appliance Manager Operator’s Guide Silver Peak Appliance Manager Operator’s Guide Document PN 200030-001 Rev Q Date: May 2016 Copyright © 2016 Silver Peak Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. Information in this document is subject to change at any time. Use of this documentation is restricted as specified in the End User License Agreement. No part of this documentation can be reproduced, except as noted in the End User License Agreement, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Silver Peak Systems, Inc. Trademark Notification The following are trademarks of Silver Peak Systems, Inc.: Silver Peak SystemsTM, the Silver Peak logo, Network MemoryTM, Silver Peak NX-SeriesTM, Silver Peak VX-SeriesTM, Silver Peak VRX-SeriesTM, Silver Peak Unity EdgeConnectTM, and Silver Peak OrchestratorTM. All trademark rights reserved. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies or organizations. Warranties and Disclaimers THIS DOCUMENTATION IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR NON-INFRINGEMENT. SILVER PEAK SYSTEMS, INC. ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR ERRORS OR OMISSIONS IN THIS DOCUMENTATION OR OTHER DOCUMENTS WHICH ARE REFERENCED BY OR LINKED TO THIS DOCUMENTATION. REFERENCES TO CORPORATIONS, THEIR SERVICES AND PRODUCTS, ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED. IN NO EVENT SHALL SILVER PEAK SYSTEMS, INC. BE LIABLE FOR ANY SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, INDIRECT OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OF ANY KIND, OR ANY DAMAGES WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE RESULTING FROM LOSS OF USE, DATA OR PROFITS, WHETHER OR NOT ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF DAMAGE, AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE USE OF THIS DOCUMENTATION. -

Council Meeting of NEW JERSEY ADVISORY COUNCIL on ELDER CARE

Council Meeting of NEW JERSEY ADVISORY COUNCIL ON ELDER CARE “Expert presentations on caregivers and caregiving of the elderly” LOCATION: Room 319 DATE: November 13, 1998 State House 9:00 a.m. Trenton, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COUNCIL PRESENT: Assemblywoman Carol J. Murphy, Chair Senator Robert W. Singer Senator Norman M. Robertson Assemblyman Samuel D. Thompson Assemblyman Louis A. Romano Len Fishman Susan C. Reinhard Ruth M. Reader Theresa L. Edelstein Renee W. Michelsen Roberto Muniz Joanne P. Robinson ALSO PRESENT: Irene M. McCarthy Office of Legislative Services Council Aide Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Gail Gibson Hunt Executive Director National Alliance for Caregiving Bethesda, Maryland 23 Carol Levine Director Families and Health Care Project United Hospital Fund New York City, New York 38 Suzanne Geffen Mintz President-Cofounder National Family Caregivers Association Kensington, Maryland 40 Suzanne Linnane State Specialist State Policy Clearinghouse National Alzheimer’s Association Washington, D.C. 54 Steven H. Zarit, Ph.D. Assistant Director Gerontology Center The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania 63 Peter S. Arno, Ph.D. Health Economist Professor Department of Epidemiology and Social Medicine Montefiore Medical Center Albert Einstein College of Medicine Bronx, New York 82 Susan R. Friedman Executive Director The Grotta Foundation for Senior Care 92 TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page Myrl Weinberg President National Health Council Washington, D.C. 105 APPENDIX: Remarks plus slide presentation submitted by Commissioner Len Fishman New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services 1x Testimony for the U.S.