READ Middle East Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

Exploring Corruption in Public Financial Management 267 William Dorotinsky and Shilpa Pradhan

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 39985 The Many Faces of Corruption The Many Faces of Corruption Tracking Vulnerabilities at the Sector Level EDITED BY J. Edgardo Campos Sanjay Pradhan Washington, D.C. © 2007 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 2 3 4 5 10 09 08 07 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgement on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

An Interview with Kanan Makiya (Part 2)

Putting Cruelty First: An Interview with Kanan Makiya (Part 2) Kanan Makiya is the Sylvia K. Hassenfeld Professor of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at Brandeis University, and the President of The Iraq Memory Foundation. His books, The Republic of Fear: Inside Saddam’s Iraq (1989, written as Samir al- Khalil) and Cruelty and Silence: War, Tyranny, Uprising and the Arab World (1993) are classic texts on the nature of totalitarianism. Makiya has also collaborated on films for television. The award-winning film, Saddam’s Killing Fields, exposed the Anfal, the campaign of mass murder conducted by the Ba’ath regime in northern Iraq in 1988. In October 1992, he acted as the convenor of the Human Rights Committee of the Iraqi National Congress. He was part of the Iraqi Opposition in the run-up to the Iraq War, which he supported as a war of liberation. The interview took place on December 16 2005. Part 1 appeared in Democratiya 3. The Iraq War Alan Johnson: In the run-up to the Iraq war few radical democrats were as close to the centres of decision-making as you, or more privy to the crucial debates. Few are in a better position to draw lessons. Can we begin in June 2002 when you are approached by the State Department and asked to participate in the Future of Iraq project? Initially you had a big clash with the State Department over the very terms of the project and of your involvement, right? What was at stake? Kanan Makiya: When I was approached I was aware events were heading towards war. -

Corruption Perceptions Index 2020

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality. #cpi2020 www.transparency.org/cpi Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of January 2021. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-157-0 2021 Transparency International. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0 DE. Quotation permitted. Please contact Transparency International – [email protected] – regarding derivatives requests. CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 2-3 12-13 20-21 Map and results Americas Sub-Saharan Africa Peru Malawi 4-5 Honduras Zambia Executive summary Recommendations 14-15 22-23 Asia Pacific Western Europe and TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE European Union 6-7 Vanuatu Myanmar Malta Global highlights Poland 8-10 16-17 Eastern Europe & 24 COVID-19 and Central Asia Methodology corruption Serbia Health expenditure Belarus Democratic backsliding 25 Endnotes 11 18-19 Middle East & North Regional highlights Africa Lebanon Morocco TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL 180 COUNTRIES. 180 SCORES. HOW DOES YOUR COUNTRY MEASURE UP? -

Iraq: Overview of Corruption and Anti-Corruption

www.transparency.org www.cmi.no Iraq: overview of corruption and anti-corruption Query Please provide an overview of corruption and anti-corruption efforts in Iraq. Purpose become increasingly aware of the enormous corruption challenges it faces. Massive embezzlement, We would like to provide all country offices with an anti- procurement scams, money laundering, oil smuggling corruption country profile to inform their contribution and widespread bureaucratic bribery have led the portfolio analysis country to the bottom of international corruption rankings, fuelled political violence and hampered Content effective state building and service delivery. 1. Overview of corruption in Iraq Although the country’s anti-corruption initiatives and framework have expanded since 2005, they still fail to 2. Anti-corruption efforts in Iraq provide a strong and comprehensive integrity system. 3. References Political interference in anti-corruption bodies and politicisation of corruption issues, weak civil society, insecurity, lack of resources and incomplete legal Caveat provisions severely limit the government’s capacity to This answer does not extensively deal with the efficiently curb soaring corruption. Ensuring the integrity specificities of the Kurdistan Regional Government of the management of Iraq’s massive and growing oil (KRG) and primarily focuses on corruption and anti- revenue will therefore be one of the country’s greatest corruption in the rest of Iraq. challenges in the coming years. Summary After a difficult beginning marked by institutional instability, Iraq’s new regime has in recent years Author(s): Maxime Agator, Transparency International, [email protected] Reviewed by: Marie Chêne, Transparency International, [email protected]; Finn Heinrich, Ph.D, [email protected] Date: April 2013 Number: 374 U4 is a web-based resource centre for development practitioners who wish to effectively address corruption challenges in their work. -

Corruption Worse Than ISIS: Causes and Cures Cures for Iraqi Corruption

Corruption Worse Than ISIS: Causes and Cures Cures for Iraqi Corruption Frank R. Gunter Professor of Economics, Lehigh University Advisory Council Member, Iraq Britain Business Council “Corruption benefits the few at the expense of the many; it delays and distorts economic development, pre-empts basic rights and due process, and diverts resources from basic services, international aid, and whole economies. Particularly where state institutions are weak, it is often linked to violence.” (Johnston 2006 as quoted by Allawi 2020) Like sand after a desert storm, corruption permeates every corner of Iraqi society. According to Transparency International (2021), Iraq is not the most corrupt country on earth – that dubious honor is a tie between Somalia and South Sudan – but Iraq is in the bottom 12% ranking 160th out of the 180 countries evaluated. With respect to corruption, Iraq is tied with Cambodia, Chad, Comoros, and Eritrea. Corruption in Iraq extends from the ministries in Baghdad to police stations and food distribution centers in every small town. (For excellent overviews of the range and challenges of corruption in Iraq, see Allawi 2020 and Looney 2008.) While academics may argue that small amounts of corruption act as a “lubricant” for government activities, the large scale of corruption in Iraq undermines private and public attempts to achieve a better life for the average Iraqi. A former Iraqi Minister of Finance and a Governor of the Central Bank both stated that the deleterious impact of corruption was worse than that of the insurgency (Minister of Finance 2005). This is consistent with the Knack and Keefer study (1995, Table 3) that showed that corruption has a greater adverse impact on economic growth than political violence. -

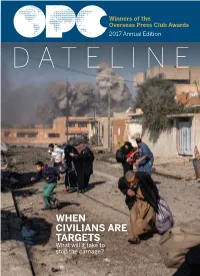

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Factors Affecting Stability in Northern Iraq

AUGUST 2009 . VOL 2 . ISSUE 8 Factors Affecting Stability government by demonstrating that they the city the “strategic center of gravity” hold a grim likelihood for success is for AQI.8 Months later, in a new in Northern Iraq less credible absent U.S. forces. For this Mosul offensive directly commanded reason, insurgents are testing the ISF on by al-Maliki called “Lion’s Roar,” the By Ramzy Mardini its capability, resolve, and credibility as lack of resistance among insurgents a fair and non-sectarian institution. disappointed some commanders who iraq entered a new security were expecting a decisive Alamo-style environment after June 30, 2009, This litmus test is most likely to battle.9 when U.S. combat forces exited Iraqi occur in Mosul, the capital of Ninawa cities in accordance with the first of Province. In its current political and Today, AQI and affiliated terrorist two withdrawal deadlines stipulated security context, the city is best situated groups, such as the Islamic State of Iraq, in the Status of Forces Agreement for insurgents to make early gains in still possess a strategic and operational (SOFA). Signed in December 2008 by propagating momentum. Geographically capacity to wage daily attacks in Mosul.10 President George W. Bush and Iraqi located 250 miles north of Baghdad Although the daily frequency of attacks Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, the along the Tigris River, Mosul is Iraq’s in Mosul dropped slightly from 2.43 SOFA concedes that December 31, 2011 second largest city with a population attacks in June 2009 to 2.35 attacks in will be the deadline for the complete of 1.8 million.2 Described as an ethnic July 2009, the corresponding monthly withdrawal of U.S. -

U4 Helpdesk Answer

U4 Helpdesk Answer U4 Helpdesk Answer 2020 11 December 2020 AUTHOR Corruption and anti- Jennifer Schoeberlein corruption in Iraq [email protected] Since the fall of Saddam Hussein in a US-led military operation in REVIEWED BY 2003, Iraq has struggled to build and maintain political stability, Saul Mullard (U4) safety and the rule of law. Deeply entrenched corruption [email protected] continues to be a significant problem in the country and a core grievance among citizens. Among the country’s key challenges, Matthew Jenkins (TI) and at the root of its struggle with corruption is its [email protected] consociationalist governance system, known as muhasasa, which many observers contend has cemented sectarianism, nepotism and state capture. Consecutive governments since 2003 have promised to tackle RELATED U4 MATERIAL corruption through economic and political reform. But, as yet, these promises have not been followed by sufficient action. This is Influencing governments on anti- partly due to an unwillingness to tackle the systemic nature of corruption using non-aid means corruption, weak institutions ill-equipped to implement reform Iraq: 2015 Overview of corruption efforts and strong opposition from vested interests looking to and anti-corruption maintain the status quo. As a result, Iraq is left with an inadequate legal framework to fight corruption and with insufficiently equipped and independent anti-corruption institutions. Trust in government and the political process has been eroded, erupting in ongoing country-wide protests against corruption, inadequate service delivery and high unemployment. This leaves the new government of Prime Minister Kadhimi, who has once more promised to tackle the country’s massive corruption challenges, with a formidable task at hand. -

Iraq's Public Administrative Issues: Corruption

inistrat dm ion A a c n li d b M u a P n Craciunescu, Review Pub Administration Manag 2017, 5:2 f a o Review of Public Administration g e w m DOI: 10.4172/2315-7844.1000207 e i e v n e t R ISSN: 2315-7844 and Management Research Article Open Access Iraq's Public Administrative Issues: Corruption Cosmina Ioana Craciunescu* Department of Public Policy Analysis, University of Babes-Bolyai, Romania *Corresponding author: Cosmina Ioana Craciunescu, Department of Public Policy Analysis, Romania, Tel: +40-741091904; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: March 20, 2017, Acc date: May 02, 2017, Pub date: May 04, 2017 Copyright: © 2016 Craciunescu CI. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Iraq has been deeply affected by corruption, particularly during the years of wars that left a heavy imprint on the country, at all levels of social functionality, including the public administrative system. Corruption is deeply rooted in Iraq, as it seemed to gain proportions with the coming of the Islamic State to power. The topic was chosen particularly because the issue of corruption represents a very important subject, also being a social phenomenon that affects the administration along with the society of Iraq. Moreover, with the coming of the Islamic State to power, corruption reached its peaks, as the organization gradually destroyed the administrative system. Along with the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, Iraq suffered from the outcomes of the disastruous management at the level of government. -

Frank R. Gunter

Frank R. Gunter M E P Produced by the Foreign Policy Research Institute. Author: Frank R. Gunter Edited by: Thomas J. Shattuck Designed by: Natalia Kopytnik © 2020 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute Our mission The Foreign Policy Research Institute is an independent nonpartisan 501(c)(3) non profit think tank based in Philadelphia, PA. FPRI was founded in 1955 by Robert Strausz-Hupe, a former U.S. ambassador. Today, FPRI’s work continues to support Strausz-Hupe’s belief that “a nation must think before it acts” through our five regional and topical research programs, education initiatives, and public engagement both locally and nationally. FPRI is dedicated to producing the highest quality scholarship and nonpartisan policy analysis focused on crucial foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. About the Author Frank R. Gunter PhD is a Senior Fellow in the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Middle East Program, a Professor of Economics at Lehigh University, and a retired U.S. Marine Colonel. After receiving his Doctorate in Political Economy from Johns Hopkins University in 1985, Dr. Gunter joined the faculty of Lehigh University where he teaches Principles of Economics, Economic Development, and the Political Economy of Iraq. He has won four major and multiple minor awards for excellence in undergraduate teaching. In 2005-2006 and 2008-2009, he served as an economic advisor to the U.S. Government in Baghdad for which he received the Bronze Star Medal and the Senior Civilian Service Award. Based on his experiences, he wrote, The Political Economy of Iraq: Restoring Balance in a Post-Conflict Society. -

ISIS in Iraq

i n s t i t u t e f o r i n t e g r at e d t r a n s i t i o n s The Limits of Punishment Transitional Justice and Violent Extremism iraq case study Mara Redlich Revkin May, 2018 After the Islamic State: Balancing Accountability and Reconciliation in Iraq About the Author Mara Redlich Revkin is a Ph.D. Candidate in Acknowledgements Political Science at Yale University and an Islamic The author thanks Elisabeth Wood, Oona Law & Civilization Research Fellow at Yale Law Hathaway, Ellen Lust, Jason Lyall, and Kristen School, from which she received her J.D. Her Kao for guidance on field research and survey research examines state-building, lawmaking, implementation; Mark Freeman, Siobhan O’Neil, and governance by armed groups with a current and Cale Salih for comments on an earlier focus on the case of the Islamic State. During draft; and Halan Ibrahim for excellent research the 2017-2018 academic year, she will be col- assistance in Iraq. lecting data for her dissertation in Turkey and Iraq supported by the U.S. Institute for Peace as Cover image a Jennings Randolph Peace Scholar. Mara is a iraq. Baghdad. 2016. The aftermath of an ISIS member of the New York State Bar Association bombing in the predominantly Shia neighborhood and is also working on research projects concern- of Karada in central Baghdad. © Paolo Pellegrin/ ing the legal status of civilians who have lived in Magnum Photos with support from the Pulitzer areas controlled and governed by terrorist groups.