Religion Thesis Swarthmore College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaknanda Basin (Uttarakhand Himalaya): a Study on Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options in an Ecologically Fragile Mountain Terrain”

Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options ICSSR PDF A Final Report On “The Alaknanda Basin (Uttarakhand Himalaya): A Study on Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options in an Ecologically Fragile Mountain Terrain” Under the Scheme of General Fellowship Submitted to Indian Council of Social Science Research Aruna Asaf Ali Marg JNU Institutional Area New Delhi By Vishwambhar Prasad Sati, Ph. D. General Fellow, ICSSR, New Delhi Department of Geography HNB Garhwal University Srinagar Garhwal, Uttarakhand E-mail: [email protected] Vishwambhar Prasad Sati 1 Enhancing and Diversifying Livelihood Options ICSSR PDF ABBREVIATIONS • AEZ- Agri Export Zones • APEDA- Agriculture and Processed food products Development Authority • ARB- Alaknanda River Basin • BDF- Bhararisen Dairy Farm • CDPCUL- Chamoli District Dairy Production Cooperative Union Limited • FAO- Food and Agricultural Organization • FDA- Forest Development Agency • GBPIHED- Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development • H and MP- Herbs and Medicinal Plants • HAPPRC- High Altitude Plant Physiology Center • HDR- Human Development Report • HDRI- Herbal Research and Development Institute • HMS- Himalayan Mountain System • ICAR- Indian Council of Agricultural Research • ICIMOD- International Center of Integrated Mountain and Development • ICSSR- Indian Council of Social Science Research LSI- Livelihood Sustainability Index • IDD- Iodine Deficiency Disorder • IMDP- Intensive Mini Dairy Project • JMS- Journal of Mountain Science • MPCA- Medicinal Plant -

Sri Chakra the Source of the Cosmos

Sri Chakra The Source of the Cosmos The Journal of the Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam, Rush, NY Blossom 22 Petal 3 December 2017 Blossom 22, Petal 3 I N Temple Bulletin 3 T Past Temple Events 4 H Upcoming Temple I Events 6 S Balancing Your Life I in the Two Modes of Existence 8 S Kundalini: A S Mosaic Perspective 11 U Sahasra Chandi 13 E Kailash Yatra 17 Ganaamritam 20 Gurus, Saints & Sages 23 Naivēdyam Nivēdayāmi 26 Kids Korner! 29 2 Sri Rajarajeswari Peetam • 6980 East River Road • Rush, NY 14543 • Phone: (585) 533 - 1970 Sri Chakra ● December 2017 TEMPLETEMPLETEMPLE BULLETINBULLETINBULLETIN Rajagopuram Project As many of you know, Aiya has been speaking about the need for a more permanent sacred home for Devi for a number of years. Over the past 40 years, the Temple has evolved into an import- ant center for the worship of the Divine Mother Rajarajeswari, Temple Links attracting thousands of visitors each year from around the world. Private Homa/Puja Booking: It is now time to take the next step in fulfilling Aiya’s vision of srividya.org/puja constructing an Agamic temple in granite complete with a tradi- tional Rajagopuram. With the grace of the Guru lineage and the Rajagopuram Project (Granite loving blessings of our Divine Mother, now is the right time to Temple): actively participate and contribute to make this vision a reality. srividya.org/rajagopuram The new Temple will be larger and will be built according to Email Subscriptions: the Kashyapa Shilpa Shastra. By following the holy Agamas, srividya.org/email more divine energy than ever will be attracted into the Tem- ple, and the granite will hold that energy for 10,000 years, bring- Temple Timings: ing powerful blessings to countless generations into the future. -

A Pilgrim's Diary to Badri, Jyoshi Mutt Etc Visited and Penned by Sri

A Pilgrim’s diary to Badri, Jyoshi mutt etc Visited and penned by Sri Varadan NAMO NARAYANAYA SRIMAN NARAYANAYA CHARANAU SARANAM PRAPATHYE SRIMATHEY NARAYANAYAH NAMAH SRI ARAVINDAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI BADRINARAYANAYA NAMAH SRI PUNDARIKAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI PURUSHOTHAMAYA NAMAH SRI PARIMALAVALLI NAYIKA SAMETHA SRI PARAMPURUSHAYA NAMAH SRIMATHE RAMANUJAYA NAMAH Due to the grace of the Divya Dampadhigal and Acharyar, Adiyen was blessed to visit Thiru Badrinath and other divya desams enroute during October,2003 along with my family. After returning from Badrinath, Adiyen also visited Tirumala-Tirupati and participated in Vimsathi darshanam a scheme which allows a family of 6 members to have Suprabatham, Nijapada and SahasraDeepalankara seva for any 2 consecutive days in a year . It was only due to the abundant grace of Thiruvengadamudaiyan adiyen was able to vist all the Divya desams without any difficulty. Before proceeding further, Adiyen would like to thank all the internet bhagavathas especially Sri Rangasri group members and M.S.Ramesh for providing abundant information about these divya desams. I have uploaded a Map of the hills again downloaded from UP Tourism site for ready reference . As Adiyen had not planned the trip in advance, it was not possible to join “package tour” organised by number of travel agencies and could not do as it was Off season. Adiyen wishes to share my experience with all of you and request the bhagavathas to correct the shortcomings. Adiyen was blessed to take my father aged about 70 years a heart patient , to this divya desam and it would not be an exaggeration to say that only because of my acharyar’s and elders’ blessings , the trip was very comfortable. -

Pilgrimage Teen Dham Yatra Haridwar to Haridwar | 06 Night / 07 Days Gangotri -Kedarnath - Badrinath

Pilgrimage Teen Dham Yatra Haridwar To Haridwar | 06 Night / 07 Days Gangotri -Kedarnath - Badrinath TOUR ITINERARY DAY 01: PICK UP HARIDWAR – UTTARKASHI /GANGNANI (140 KMS / 07 HRS) Hotel Meal Sightseeing Pick up from Haridwar Railway Station, to board and proceed to Uttarkashi Hotel. Check Inn Hotel & Uttarkashi visit Kashi Vishwanath Temple and drive to Gangnani . Evening free for leisure. Dinner & overnight stay at Uttarkashi. UTTARKASHI: Uttarkashi is a small and beautiful town, situated between two rivers; Varuna and Ashi, whose water ow into the Bhagirathi from either side of the town. Elevated, at a height of 1588 meters, this little town is very similar to Kashi and Varanasi, in that it has the same kind of temples and ghats and likewise, a north or 'uttar' facing river. The major temple is the Vishwanath Temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva. Two other very important temples are located in the Chowk area. These are the Annapurna Temple and the Bhairav Temple. It is said, that once there were 365 temples here. Hiuen Tsang referred to this place as Brahma Puran, while the Skanda Puran has recorded it as Varunavata. It is believed that in the second millennium of Kaliyug, Kashi will be submerged, and Uttarkashi will replace it as an important religious centre. UTTARKASHI / GANGNANI – GANGOTRI – HARSIL – DAY 02: GANGNANI / UTTARKASHI (120KMS / 05 HRS) ROUND TRIP Hotel Meal Sightseeing Early Morning start driving to Gangotri. Oering prayers & pooja darshan, later drive back to Uttarkashi, en route visit Gang- nani. Overnight stay at Gangnani/ Uttarkashi GANGOTRI: Gangotri temple is 18th Century temple dedicated to Goddess Ganga. -

This Guy's Adventure Filled One Week Trip to Valley of Flowers, Hemkund Sahib, Badrinath and India's Last Village - Mana

This Guy's Adventure Filled One Week Trip to Valley of Flowers, Hemkund Sahib, Badrinath and India's Last Village - Mana (7 nights, 8 days) Tour Route: Rishikesh – Govind Ghat – Ghangria – Govind Ghat – Mana – Badrinath – Govind Ghat – Rishikesh Tour Duration: 7 nights, 8 days Estimate travel dates: August 7-14 Group size: 20 people ********************************************************************************************* Brief Itinerary August 7: Meet at Rishikesh at 5 am sharp. Leave for Govind Ghat. August 8, Monday: Govind Ghat to Ghangria via Poolna. August 9: Ghangria to Valley of Flowers and back. August 10: Ghangria to Hemkund Sahib and back. August 11: Descend to Poolna. Drive back to Govind Ghat. August 12: Day visit to Mana village and Badrinath. August 13: Govind Ghat to Rishikesh. August 14: After early breakfast, depart for your respective cities. Note: People can arrive at Rishikesh on August 6th night (please note: trippers can make their own arrangements for this night or book your accommodation with us for an extra charge.) or reach directly on August 7th morning any time before 5 am. On August 14th people can leave any time in the morning. Trek Information: In the Chamoli district of Uttarakhand lies a palette of colours for you to trek and explore. With one side where tall cliffs greet the sky, the other side covered in snow clad mountains and a serene river meandering between the two, we present to you a picture-perfect trek. With approximately 80 species of flowers growing in the valley, the sight is nothing short of a treat for the eyes. While rainfall can be expected during our trip’s dates, July is still considered one of the best months to visit the valley as the monsoon is when the flowers are in full bloom. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Chardham Yatra 2020

CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 1 ç Om Namah Shivaya CHARDHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions, Nepal www.karnaliexcursions.com CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 2 Fixed Departure Dates Starts in Delhi Ends in Delhi 1. 14 Sept, 2020 28 Sept, 2020 2. 21 Sept, 2020 5 Oct, 2020 3. 28 Sept, 2020 12 Oct, 2020 India is a big subject, with a diversity of culture of unfathomable depth, and a long Yatra continuum of history. India offers endless opportunities to accumulate experiences Overview: and memories for a lifetime. Since very ancient >> times, participating in the Chardham Yatra has been held in the highest regard throughout the length and breadth of India. The Indian Garhwal Himalayas are known as Dev-Bhoomi, the ‘Abode of the Gods’. Here is the source of India’s Holy River Ganges. The Ganges, starting as a small glacial stream in Gangotri and eventually travelling the length and breadth of India, nourishing her people and sustaining a continuum of the world’s most ancient Hindu Culture. In the Indian Garhwal Himalayas lies the Char Dham, 4 of Hinduism’s most holy places of pilgrimage, nestled in the high valleys of the Himalayan Mountains. Wearing the Himalayas like a crown, India is a land of amazing diversity. Home to more than a billion people, we will find in India an endless storehouse of culture and tradition amidst all the development of the 21st century! CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 3 • A complete darshan of Char Dham: Yamunotri, Trip Gangotri, Kedharnath and Badrinath. -

Tapovan-Trek.Pdf

GAUMUKH - TAPOVAN the holy trail TREK ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Gangotri Day 2 Gangotri - Chirbasa (Trek: 09kms) Day 3 Chirbasa - Bhojwasa - Gaumukh Glacier - Bhojwasa (Trek: 13kms) Day 4 Bhojwasa - Tapovan - Kala Pathar (Trek: 10kms) Day 5 Tapovan - Bhojwasa (Trek: 10kms) Day 6 Bhojwasa - Gangotri (Trek: 14kms) Trek Service Ends ALTITUDE GRAPH 4,600 S 3,450 T M N I 2,300 E D U T I T L 1,150 A 0 Gangotri Chirbasa Bhojwasa Gaumukh Glacier Tapovan Meru Glacier Gangotri The most satisfying treks in the Garhwal Himalayas where you not only camp at the foot of lofty Himalayan peak but also cross the massive Gaumukh Glacier, the origin of Ganga River. The best way to put this trek in three words would be – the holy trail. The trekking route is open for trekkers and pilgrims from May to October. INCLUSIONS 1N STAY ALL MEALS & ALL CAMPING IN GANGOTRI PACKED LUNCH EQUIPMENTS GUIDE, COOK, NATIONAL PARK HELPER & PERMIT & PORTER FEE CAMPING FEE TREK HIGHLIGHTS Visit the sacred Gangotri Temple. Trek to the source of sacred Ganga River -Gaumukh Glacier. Camp at the Foot of celebrate Himalayan peaks like Shivling overlooking Bagirathi, Meru, Kharchkund & other enormous peaks. Wide variety of flora and fauna – Gangotri National Park. Perfect introduction to high altitude trekking. GAUMUKH - TAPOVAN TREK FEE Group Package starting from Rs. 20000/-pp + 5% GST (Ex-Gangotri) Premium Customized Trek Rs. 26000/-pp + 5% GST (Ex-Gangotri) Transportation Charges Extra Backpack Offloading Charges: Rs. 500 per bag per day (upto 10kgs) W H Y B O O K W I T H U S E U T T A R A N C H A L L E S S I S M O R E M A R K E T I N G G U R U S M A L L B A T C H S I Z E At eUttaranchal we have been We keep our batch size limited promoting & catering travel and charge trek fee accordingly. -

Yatra Special

The Hope Yatra A Journey of Help & Healing in the Himalayas H.H. Swami Chidanand Saraswatiji June 2015 News Special Pujya Swamiji makes Historic yatra of giving, caring and sharing in the service of God and Humanity Inside Sacred Memorial Garden Enabling Self-Sufficient Lives Darshan at A Beautiful New School in Kedarnath for Disaster Widows Holy Kedarnath in the Flood-Devastated Himalayas |Parmarth Niketan News 1 THE HOPE YATRA 2015 Contents Green Pilgrimage 3 Historic Inauguration 4 Joy at a Newly-Rebuilt School 8 Rebuilding Lives and Livlihoods 14 Journey to Rambada: Site of Deadly Landslide to be Transformed 18 Hope in Agustyamuni 20 A New Vision for the Agustyamuni Training Center 23 At the Sacred Confluence of Rudra Prayag 24 Divinity at Devprayag 26 Shri Vidya Dham, Guptakashi 29 Darshan in Holy Kedarnath, Graced by Heavenly Snowfalls 30 Learn More! Visit our Websites By Clicking: www.parmarth.com (Parmarth Niketan Rishikesh), www.gangaaction.org (Ganga Action Parivar), www.washalliance.org (Global Interfaith WASH Alliance), www.projecthope-india.org (Project Hope), www.divineshaktifoundation.org (Divine Shakti Foundation), www.ihrf.com (India Heritage Research Foundation) |Parmarth Niketan News 2 THE HOPE YATRA 2015 Green Pilgrimage. Throughout the world, the act of pilgrimage represents a sacred journey of body, mind and soul, which enriches lives as travellers walk towards the vistas, holy places and people that symbolize the heart of spirituality. In the spring of 2015, HH Pujya Swami Chidanand Saraswatiji, Sadhvi Bhagawatiji and many caring souls set forth on pilgrimage to the holy shrine of Kedarnath, giving back through acts in service to God and humanity—from opening a beautiful new school to helping disaster-impacted widows to earn livelihoods— with nearly every step. -

Badrinath-Kedarnath-By-Helicopter-Do

LUXURY CHARDHAM HELICOPTER SERVICES INDIA DO DHAM YATRA BY HELICOPTER PACKAGE – BADRINATH KEDARNATH YATRA Home Send your enquiry on Whatsapp No.:- 9837937948 For Urgent reply. Email us - [email protected] LUXURY Charter Service India DO DHAM YATRA BY HELICOPTER PACKAGE • Rs. 90,000/- Per Person Same Day • Rs. 110,000/- Per Person Overnight Stay • Maximum 5/6 Passengers in 1 Helicopter (Subject to weight not exceeding 400 kgs). Route Map : Dehradun - Kedarnath – Badrinath – Dehradun (Subject to weather conditions) Send your enquiry on Whatsapp No.:- 9837937948 For Urgent reply. Email us - [email protected] ITINERARY DAY 1 • 06:00hrs - Departure from Dehradun Sahastradhara heliport. • 07:00hrs - Arrival at Guptkashi/Phata, Due to Government regulation, you will have to change helicopter. Upon arrival at Kedarnath Dham, you will be met by our ground personnel, who will escort you to the holy shrine. We will offer V.I.P darshan slips of Kedarnath temple so you can avoid the long queue and finish darshan quickly. • 09:00hrs - Depart from Shri Kedarnath Dham by Helicopter to change helicopter at Guptkashi/Phata for Badrinath Dham. • 10:00hrs - Arrival at Badrinath, upon arrival you will be provided a car which will take you to Badrinath Temple where you will perform darshan following which you head back to the Helipad in the same car. • 12:40hrs - Departure from Badrinath by Helicopter • 13:30hrs - Arrival at Dehradun (Sahastradhara Helipad) DAY 2 With Stay in Badrinath • Refresh yourself with a comfortable Night Stay with a complimentary dinner in a Deluxe Hotel at Badrinath • 06:00hrs Return to Dehradun. Arrived at Helipad Dehradun further onwards Journey. -

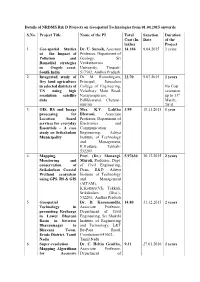

Details of NRDMS R& D Projects on Geospatial Technologies From

Details of NRDMS R& D Projects on Geospatial Technologies from 01.04.2015 onwards S.No. Project Title Name of the PI Total Sanction Duration Cost (In Date of the lakhs) Project 1. Geo-spatial Studies Dr. U. Suresh, Assistant 24.186 9.04.2015 3 years of the Impact of Professor, Department of Pollution and Geology, Sri Remedial strategies Venkateswara in Ongole coast, University, Tirupati- South India 517502, Andhra Pradesh 2. Integrated study of Dr. M. Ramalingam, 22.70 9.07.2015 2 years Dry land agriculture Principal, Jerusalem in selected districts of College of Engineering, No Cost TN using high Velachery Main Road, extension resolution satellite Narayanapuram, up to 31st data Pallikkaranai, Chennai- March, 600100 2018 3. GIS, RS and Image Mrs. K.V. Lalitha 3.99 19.11.2015 1 year processing for Bhavani, Associate Location based Professor, Department of services for everyday Electronics and Essentials – A case Communication study on Srikakulam Engineering, Aditya Municipality Institute of Technology and Management, K.Kotturu, Tekkali- 532201 4. Mapping, Prof. (Dr.) Monangi. 5.97630 30.12.2015 2 years Monitoring and Murali, Professor, Dept. conservation of of Civil Engineering, Srikakulam Coastal Dean, R&D, Aditya Wetland ecosystem Institute of Technology using GPS, RS & GIS and Management (AITAM), K.Kotturu(VI), Tekkali, Srikakulam (Dist.)- 532201, Andhra Pradesh 5. Geospatial Dr. D. Karunanidhi, 14.80 31.12.2015 2 years Technology in Associate Professor, promoting Recharge Department of Civil in Lower Bhavani Engineering, Sri Shakthi Basin in between Institute of Engineering Bhavanisagar to and Technology, L&T Bhavani Town, By-Pass Road, Erode District, Tamil Coimbatore-641062, Nadu Tamil Nadu 6. -

Longitudinal Distribution of the Fish Fauna in the River Ganga from Gangotri to Kanpur

AL SCI UR EN 63 T C A E N F D O N U A N D D A E I Journal of Applied and Natural Science 5 (1): 63-68 (2013) T L I O P N P A JANS ANSF 2008 Longitudinal distribution of the fish fauna in the river Ganga from Gangotri to Kanpur Prakash Nautiyal*, Asheesh Shivam Mishra, K.R. Singh1 and Upendra Singh Aquatic Biodiversity Unit, Department of Zoology and Biotechnology, HNB Garhwal University Srinagar- 246174 (Uttarakhand), INDIA 1K.L. Degree College, Allahabad- 211002( UP), INDIA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Received:October 1, 2012; Revised received: January 31, 2013; Accepted:February 25, 2013 Abstract: Fish fauna of the river Ganga from Gangotri to Kanpur consisted of 140 fish species from 9 orders and 25 families; 63 fish species from 6 orders and 12 families in the mountain section (MS), while 122 species from 9 orders and 25 families in the Plains section (PS) of Upper Ganga. Cypriniformes and Cyprinidae were most species rich order and family in both sections. Forty six fish species primarily Cypriniformes and Siluriformes are common to both sections, only 17 in MS and 76 in PS. Orders Tetradontiformes, Osteoglossiformes and Clupeiformes were present in PS only. The taxonomic richness in the MS was low compared to PS. Probably motility and physiological requirements in respect of tolerance for temperature restrict faunal elements. Keywords: Cyprinidae, Fish distribution, Gangetic plains, Himalaya, River continuum INTRODUCTION available on the longitudinal distribution of fish fauna in Distributional patterns of organisms are controlled by the Ganga river especially from mountain (Gangotri to dispersal mechanism, historical factors (connecting Haridwar) to upper plain section (Haridwar to Kanpur).