Neill, Rebecca MH (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

The Succession After Kumaragupta I

Copyright Notice This paper has been accepted for publication by the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, which is published by Cambridge University Press. A final version of the article will be appearing in the JRAS in 2014. 1 The Succession after Kumāragupta I Pankaj Tandon1 Most dynastic lists of the Gupta kings state that Kumāragupta I was succeeded by Skandagupta. However, it is widely accepted that Skandagupta did not accede to the throne peacefully. Nor is it certain that the succession was immediate, since there is a gap between the known dates of Kumāragupta’s and Skandagupta’s reigns. This paper is concerned with the events following the death of Kumāragupta, using numismatic evidence as the primary source, and inscriptional and other epigraphic evidence as further support. Some of the numismatic evidence is new, and even the evidence that is not new has so far received little attention in the literature on the succession after Kumāragupta. Questions are raised about one particular theory that is presently enjoying some currency, that Skandagupta was challenged primarily by his uncle Ghaṭotkacagupta. Some other possible scenarios for the political events in the period after the death of Kumāragupta I will then be proposed and analyzed. Most authors agree that Skandagupta was not the rightful heir to the throne. While he does announce himself on his inscriptions as the son of Kumāragupta I, his mother is not identified by name in any known text or inscription,2 suggesting that he was, at best, the son of a minor queen of Kumāragupta, or more probably the son of a woman who was not a queen at all. -

New Fuller Ebook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms

New Fuller eBook Acquisitions - Courtesy of Ms. Peggy Helmerick Publication Title eISBN Handbook of Cities and the Environment 9781784712266 Handbook of US–China Relations 9781784715731 Handbook on Gender and War 9781849808927 Handbook of Research Methods and Applications in Political Science 9781784710828 Anti-Corruption Strategies in Fragile States 9781784719715 Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality 9781785367267 Politics of Persuasion, The 9781782546702 Individualism and Inequality 9781784716516 Handbook on Migration and Social Policy 9781783476299 Global Regionalisms and Higher Education 9781784712358 Handbook of Migration and Health 9781784714789 Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting 9781784715922 Trust, Social Capital and the Scandinavian Welfare State 9781785365584 Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers, Forest Conservation and Climate Change 9781784716608 Handbook of Transnational Environmental Crime 9781783476237 Cities as Political Objects 9781784719906 Leadership Imagination, The 9781785361395 Handbook of Innovation Policy Impact 9781784711856 Rise of the Hybrid Domain, The 9781785360435 Public Utilities, Second Edition 9781785365539 Challenges of Collaboration in Environmental Governance, The 9781785360411 Ethics, Environmental Justice and Climate Change 9781785367601 Politics and Policy of Wellbeing, The 9781783479337 Handbook on Theories of Governance 9781782548508 Neoliberal Capitalism and Precarious Work 9781781954959 Political Entrepreneurship 9781785363504 Handbook on Gender and Health 9781784710866 Linking -

Selected Bibliography

432 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Abbott, Terry Rae. Vasubandhu's Commentary to the 'SaddharmapuŸÖarîka-sûtra': A Study of its History and Significance. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, 1986. Ahmed, Nisar. "A Re-examination of the Genealogy and Chronology of the Vâkâ¡akas," Indian Antiquary. ser. 3. 4 (1970): 149-164. Alexander, James Edward. "Notice of a Visit to the Cavern Temples of Adjunta in the East Indies," Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 (1830): 362-70. Allen, John. "A Note on the Inscriptions of Cave II." Appendix to Ghulam Yazdani. Ajanta. vol. 2. London: Oxford University Press, 1933. Apte, Vaman Shivram. The Student's Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1970. AsaÝga. Bodhisattvabhûmi. Ed. by Nalinaksha Dutt. Patna: Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute, 1978. _____. Mahâyâna Sûtralaœkâra. Ed. by Dwarika Das Shastri. Varanasi: Bauddha Bharati, 1985. AÑvagho§a. AÑvagho§a's Buddhacarita, or, Acts of the Buddha. Ed. and trans. by E. H. Johnston. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984. _____. The Saundarananda of AÑvagho§a. Ed. and trans. by E. H. Johnston. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1975. Auboyer, Jeannine. Le Trône et son symbolisme dans l'Inde ancienne. Annales de Musée Guimet, Bibl. d'étdudes 55. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1949. _____. "Un aspect du symbolisme de la souveraineté dans l'Inde d'après l'iconographie des trônes," Revue des arts asiatiques. XI (1937): 88-101. Bagchi P. C. "The Eight Great Caityas and their Cult," Indian Historical Quarterly 2 (1941): 223-235. Bailey, Harold. The Culture of the Sakas in Ancient Iranian Khotan. Delmar, NY: Caravan Publishers, 1982. -

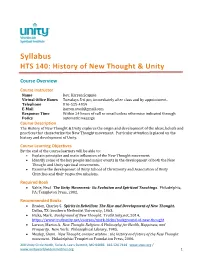

HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity

Syllabus HTS 140: History of New Thought & Unity Course Overview Course Instructor Name Rev. Karren Scapple Virtual Office Hours Tuesdays 5-6 pm, immediately after class and by appointment. Telephone 816-525-4059 E-Mail [email protected] Response Time Within 24 hours of call or email unless otherwise indicated through Policy automatic message Course Description The History of New Thought & Unity explores the origin and development of the ideas, beliefs and practices that characterize the New Thought movement. Particular attention is placed on the history and development of Unity. Course Learning Objectives By the end of the course learners will be able to: • Explain principles and main influences of the New Thought movement. • Identify some of the key people and major events in the development of both the New Thought and Unity spiritual movements. • Examine the development of Unity School of Christianity and Association of Unity Churches and their respective missions. Required Book • Vahle, Neal. The Unity Movement: Its Evolution and Spiritual Teachings. Philadelphia, PA: Templeton Press, 2002. Recommended Books • Braden, Charles S. Spirits in Rebellion: The Rise and Development of New Thought. Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University, 1963. • Hicks, Mark. Background of New Thought. TruthUnity.net, 2014. https://www.truthunity.net/courses/mark-hicks/background-of-new-thought • Larson, Martin A. New Thought Religion: A Philosophy for Health, Happiness, and Prosperity. New York: Philosophical Library, 1985. • Mosley, Glenn. New Thought, ancient wisdom : the history and future of the New Thought movement. Philadelphia: Templeton Foundation Press, 2006. 200 Unity Circle North, Suite A, Lee’s Summit, MO 64086 816.524.7414 www.uwsi.org / www.unityworldwideministries.org 1 • Shepherd, Thomas. -

1 Chief Commissioner of Income

Sl. No. Name of the Office CPIO Appellate Authority DC/ACIT (HQ), O/O CCIT, HUBLI, CCIT, HUBLI Income-tax Campus, CHIEF COMMISSIONER Gandhi Nagar, Gokul 1 C.R. Building, Hubli OF INCOME TAX, HUBLI Road, Hubli Ph.No. 0836-2323481 Ph.No. 0836-2225012 Fax: 2223889 Fax: 2223889 DC/ACIT (HQ), O/O CIT, HUBLI CIT, HUBLI Naveen Park COMMISSIONER OF Gandhi Nagar, Gokul Kusugal Road, Hubli 2 INCOME TAX, HUBLI Road, Hubli Ph.No. 0836-2223044 Ph.No. 0836-2225012 Fax no 0836-2223122 Fax No. 2223889 COMMISSIONER OF INCOME TAX CCIT, HUBLI (APPEALS), HUBLI Income-tax Campus, COMMISSIONER OF C.R. Building, C.R. Building, Hubli 3 INCOME TAX (APPEALS), Navanagar, Ph.No. 0836-2323481 HUBLI Hubli – 580025 Fax: 2223889 Ph. No. 0836-2322260 Fax : 2225358 ADDL./JCIT, RANGE-1, CIT, HUBLI HUBLI Naveen Park IT Guest House, ADDL./JCIT, RANGE-1, Kusugal Road, Hubli 4 Navanagar,HUBLI HUBLI Ph.No. 0836-2323159 Ph.No. 0836-2211959 Fax:2223122 Fax: 2322895 ADDL./JCIT, RANGE-1, DC/ACIT, CIRCLE-1(1), IT Guest House, HUBLI DC/ACIT, CIRCLE-1(1), Navanagar, HUBLI 5 17 Vidyanagar, Hubli HUBLI Ph.No. 0836-2211959 Ph.No. 0836-2323313 Fax : 2322895 INCOME TAX OFFICER, ADDL./JCIT, RANGE-1, WARD-1(1), HUBLI IT Guest House, INCOME TAX OFFICER, 23, 1st Floor, Navanagar,HUBLI 6 WARD-1(1), HUBLI Aswamedha Plot, Ph.No. 0836-2211959 Navanagar, Hubli Fax : 2322895 Ph.No. 0836-2225601 INCOME TAX OFFICER, ADDL./JCIT, RANGE-1, WARD-1(2), HUBLI IT Guest House, INCOME TAX OFFICER, 21/A, ‘Kalikarupa’ , Navanagar,HUBLI 7 WARD-1(2), HUBLI Udayanagar, Bengeri Ph.No. -

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes Posted On April 28, 2020 By Cgpsc.Info Home » CGPSC Notes » History Notes » Gupta Empire and Their Rulers Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – The Gupta period marks the important phase in the history of ancient India. The long and e¸cient rule of the Guptas made a huge impact on the political, social and cultural sphere. Though the Gupta dynasty was not widespread as the Maurya Empire, but it was successful in creating an empire that is signiÛcant in the history of India. The Gupta period is also known as the “classical age” or “golden age” because of progress in literature and culture. After the downfall of Kushans, Guptas emerged and kept North India politically united for more than a century. Early Rulers of Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) :- Srigupta – I (270 – 300 C.E.): He was the Ûrst ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) who established Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) with Pataliputra as its capital. Ghatotkacha Gupta (300 – 319 C.E): Both were not sovereign, they were subordinates of Kushana Rulers Chandragupta I (319 C.E. to 335 C.E.): Laid the foundation of Gupta rule in India. He assumed the title “Maharajadhiraja”. He issued gold coins for the Ûrst time. One of the important events in his period was his marriage with a Lichchavi (Kshatriyas) Princess. The marriage alliance with Kshatriyas gave social prestige to the Guptas who were Vaishyas. He started the Gupta Era in 319-320C.E. Chandragupta I was able to establish his authority over Magadha, Prayaga,and Saketa. Calendars in India 58 B.C. -

Utilization of 'Urni' in Our Daily Life

International Journal of Research p-ISSN: 2348-6848 e-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 03 Issue 12 August 2016 Utilization of ‘Urni’ in Our Daily Life Mr. Ashis Kumar Pradhan1, Dr. Subimalendu Bikas Sinha 2 1Research Scholar, Bhagwant University, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India 2 Emeritus Fellow, U.G.C and Ex Principal, Indian college arts & Draftsmanship, kolkata “Urni‟ is manufactured by few weaving Abstract techniques with different types of clothing. It gained ground as most essential and popular „Urni‟ is made by cotton, silk, lilen, motka, dress material. Starting in the middle of the tasar & jute. It is used by men and women. second millennium BC, Indo-European or „Urni‟ is an unstitched and uncut piece of cloth Aryan tribes migrated keen on North- Western used as dress material. Yet it is not uniformly India in a progression of waves resulting in a similar in everywhere it is used. It differs in fusion of cultures. This is the very juncture variety, form, appearance, utility, etc. It bears when latest dynasties were formed follow-on the identity of a country, region and time. the flourishing of clothing style of which the „Urni‟ was made in different types and forms „Urni‟ type was a rarely main piece. „Urni‟ is a for the use of different person according to quantity of fabric used as dress material in position, rank, purpose, time and space. Along ancient India to cover the upper part of the with its purpose as dress material it bears body. It is used to hang from the neck to drape various religious values, royal status, Social over the arms, and can be used to drape the position, etc. -

The Guptas 7

www.tntextbooks.in SPLIT BY - SIS ACADEMY https://t.me/SISACADEMYENGLISHMEDIUM Lesson The Guptas 7 Learning Objectives To learn the importance of Gupta rule in Indian history. To understand the significance of land grants and its impact on agricultural economy of the empire. To acquaint ourselves with the nature of the society and the socio-economic life of the people of the time. To know the development of culture, art and education during the period. Introduction a golden age, it is not entirely accurate. After the Mauryan empire, many small Many scholars would, however, agree that kingdoms rose and fell. In the period from it was a period of cultural florescence and c. 300 to 700 CE, a classical pattern of an a classical age for the arts. imperial rule evolved, paving the way for state formation in many regions. During Sources this period, the Gupta kingdom emerged There are three types of sources for as a great power and achieved the political reconstructing the history of the Gupta unification of a large part of the Indian period. subcontinent. It featured a strong central government, bringing many kingdoms I. Literary sources under its hegemony. Feudalism as an Narada, Vishnu, Brihaspati and institution began to take root during this Katyayana smritis. period. With an effective guild system and overseas trade, the Gupta economy Kamandaka’s Nitisara, a work on boomed. Great works in Sanskrit were polity addressed to the king (400 CE) produced during this period and a high Devichandraguptam and level of cultural maturity in fine arts, Mudrarakshasam by Vishakadutta sculpture and architecture was achieved. -

Wbcs Prelims 2020 (Feb-Nov 2019)

ANCIENT HISTORY for WBCS PRELIMS 2020 (FEB-NOV 2019) JITIN YADAV, IAS ANCIENT HISTORY NOTES FOR WBCS PRELIMS 2020 BY JITIN YADAV, IAS 1 CONTENTS S. No. TOPIC PAGE 1. Sources of India History 3 2. Pre-Historic Period 6 3. Indus Valley Civilization 6 4. Vedic Civilization 9 5. Later Vedic Period 12 6. Jainism 14 7. Buddhism 15 8. Pre-Mauryan Period 17 9. Mauryan Period 18 10. Pre-Gupta Period 20 11. Gupta Dynasty 21 12. Sangam Age 24 13. Ruling Kingdoms of South 27 14. Bengal – Palas and Senas 30 ANCIENT HISTORY NOTES FOR WBCS PRELIMS 2020 BY JITIN YADAV, IAS 2 ANCIENT HISTORY FOR WBCS PRELIMS 2020 SOURCES OF INDIAN HISTORY 1. LITERARY SOURCE • PROTO HISTORIC PERIOD (betWeen pre history and history) o Harrapan script o Vedic literature o Mathematics books § Salva Satra – earliest text of geometry § Aryabhatta – describe decimal system and about zero § Bhaskaracharya – wrote Lilavati o Architecture books § Shilpa Sastra – manual of architecture § Visnudharmattara Purana – information about painting & iconometry o Biographical Literature Author Book Banabhatta Harshacharita Vilhan Vikramanakdev charitram Ananda Bhatta Ballal Charita Sandhyakarnandi Rampal charita Jayanak Prithavi Raj Charita Hemchandra Kumarpal Charitra o Classical Sanskrit Author Book Bhasa Wrote 14 plays Asvaghosh i)Buddha Charitam ii)Sutralankar -philosophy Sudraka Mrichcha Katikam- 1st realistic Sanskrit play Visakhadutta i) Mudrarakshasa –about Kautilya ii) Devi Chandraguptam – about Chandra Gupta Vikramaditya o Statecraft § Arthashastra • Polity book by Kautilya • Book discovered by Sham Ji Shastri ANCIENT HISTORY NOTES FOR WBCS PRELIMS 2020 BY JITIN YADAV, IAS 3 • It has 15 Adhikarnas • Provide details about administration during Mauryan period o Histography – Kalhan Wrote Rajtarangini (history of Kashmir) o Buddhist Literature § Tripitaka • Sutra Pitak – teaching & preaching of Lord Buddha • Vinay Pitak – Monastical rules & regulations • Abhidharma Pitak – Metaphysical & esoteric ideas 2. -

16-Sanskrit-In-JAPAN.Pdf

A rich literary treasure of Sanskrit literature consisting of dharanis, tantras, sutras and other texts has been kept in Japan for nearly 1400 years. Entry of Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures into Japan was their identification with the central axis of human advance. Buddhism opened up unfathomed spheres of thought as soon as it reached Japan officially in AD 552. Prince Shotoku Taishi himself wrote commentaries and lectured on Saddharmapundarika-sutra, Srimala- devi-simhanada-sutra and Vimala-kirt-nirdesa-sutra. They can be heard in the daily recitation of the Japanese up to the day. Palmleaf manuscripts kept at different temples since olden times comprise of texts which carry immeasurable importance from the viewpoint of Sanskrit philology although some of them are incomplete Sanskrit manuscripts crossed the boundaries of India along with the expansion of Buddhist philosophy, art and thought and reached Japan via Central Asia and China. Thousands of Sanskrit texts were translated into Khotanese, Tokharian, Uigur and Sogdian in Central Asia, on their way to China. With destruction of monastic libraries, most of the Sanskrit literature perished leaving behind a large number of fragments which are discovered by the great explorers who went from Germany, Russia, British India, Sweden and Japan. These excavations have uncovered vast quantities of manuscripts in Sanskrit. Only those manuscripts and texts have survived which were taken to Nepal and Tibet or other parts of Asia. Their translations into Tibetan, Chinese and Mongolian fill the gap, but partly. A number of ancient Sanskrit manuscripts are strewn in the monasteries nestling among high mountains and waterless deserts. -

The Vakatakas

CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS or THE VAKATAKAS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA CORPUS INSCRIPTIONUM INDICARUM VOL. V INSCRIPTIONS OF THE VAKATAKAS EDITED BY Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi, M.A., D.Litt* Hony Piofessor of Ancient Indian History & Culture University of Nagpur GOVERNMENT EPIGRAPHIST FOR INDIA OOTACAMUND 1963 Price: Rs. 40-00 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA PLATES PWNTED By THE MRECTOR; LETTERPRESS P WNTED AT THE JQB PREFACE after the of the publication Inscriptions of the Kalachun-Chedi Era (Corpus Inscrip- tionum Vol in I SOON Indicarum, IV) 1955, thought of preparing a corpus of the inscriptions of the Vakatakas for the Vakataka was the most in , dynasty glorious one the ancient history of where I the best Vidarbha, have spent part of my life, and I had already edited or re-edited more than half the its number of records I soon completed the work and was thinking of it getting published, when Shri A Ghosh, Director General of Archaeology, who then happened to be in Nagpur, came to know of it He offered to publish it as Volume V of the Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Series I was veiy glad to avail myself of the offer and submitted to the work the Archaeological Department in 1957 It was soon approved. The order for it was to the Press Ltd on the printing given Job (Private) , Kanpur, 7th 1958 to various July, Owing difficulties, the work of printing went on very slowly I am glad to find that it is now nearing completion the course of this I During work have received help from several persons, for which I have to record here my grateful thanks For the chapter on Architecture, Sculpture and I found Painting G Yazdam's Ajanta very useful I am grateful to the Department of of Archaeology, Government Andhra Pradesh, for permission to reproduce some plates from that work Dr B Ch Chhabra, Joint Director General of Archaeology, went through and my typescript made some important suggestions The Government Epigraphist for India rendered the necessary help in the preparation of the Skeleton Plates Shri V P.