Terra Nova / Terra Nullius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

26 in the Mid-1980'S, Noise Music Seemed to Be Everywhere Crossing

In the mid-1980’s, Noise music seemed to be everywhere crossing oceans and circulating in continents from Europe to North America to Asia (especially Japan) and Australia. Musicians of diverse background were generating their own variants of Noise performance. Groups such as Einstürzende Neubauten, SPK, and Throbbing Gristle drew larger and larger audiences to their live shows in old factories, and Psychic TV’s industrial messages were shared by fifteen thousand or so youths who joined their global ‘television network.’ Some twenty years later, the bombed-out factories of Providence, Rhode Island, the shift of New York’s ‘downtown scene’ to Brooklyn, appalling inequalities of the Detroit area, and growing social cleavages in Osaka and Tokyo, brought Noise back to the center of attention. Just the past week – it is early May, 2007 – the author of this essay saw four Noise shows in quick succession – the Locust on a Monday, Pittsburgh’s Macronympha and Fuck Telecorps (a re-formed version of Edgar Buchholtz’s Telecorps of 1992-93) on a Wednesday night; one day later, Providence pallbearers of Noise punk White Mice and Lightning Bolt who shared the same ticket, and then White Mice again. The idea that there is a coherent genre of music called ‘Noise’ was fashioned in the early 1990’s. My sense is that it became standard parlance because it is a vague enough category to encompass the often very different sonic strategies followed by a large body of musicians across the globe. I would argue that certain ways of compos- ing, performing, recording, disseminating, and consuming sound can be considered to be forms of Noise music. -

Clever Children: the Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music?

Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music Author Carter, David Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1356 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367632 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music? David Carter B.Music / Music Technology (Honours, First Class) Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy 19 June 2008 Keywords Contemporary Music; Dance Music; Disco; DJ; DJ Spooky; Dub; Eight Lines; Electronica; Electronic Music; Errata Erratum; Experimental Music; Hip Hop; House; IDM; Influence; Techno; John Cage; Minimalism; Music History; Musicology; Rave; Reich Remixed; Scanner; Surface Noise. i Abstract In the late 1990s critics, journalists and music scholars began referring to a loosely associated group of artists within Electronica who, it was claimed, represented a new breed of experimentalism predicated on the work of composers such as John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Steve Reich. Though anecdotal evidence exists, such claims by, or about, these ‘Clever Children’ have not been adequately substantiated and are indicative of a loss of history in relation to electronic music forms (referred to hereafter as Electronica) in popular culture. With the emergence of the Clever Children there is a pressing need to redress this loss of history through academic scholarship that seeks to document and critically reflect on the rhizomatic developments of Electronica and its place within the history of twentieth century music. -

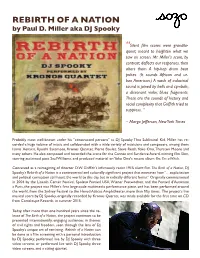

REBIRTH of a NATION by Paul D

REBIRTH OF A NATION by Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky “Silent film scores were grandilo- quent, meant to heighten what we saw on screen. Mr. Miller's score, by contrast, deflects our responses, then alters them. A hip-hop drum beat pulses. (It sounds African and ur- ban American.) A wash of industrial sound is joined by bells and cymbals; a dissonant violin; blues fragments. These are the sounds of history and racial complexity that Griffith tried to suppress. ” – Margo Jefferson, New York Times Probably most well-known under his "constructed persona" as DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid, Miller has re- corded a huge volume of music and collaborated with a wide variety of musicians and composers, among them Iannis Xenakis, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Kronos Quartet, Pierre Boulez, Steve Reich, Yoko Ono, Thurston Moore and many others. He also composed and recorded the score for the Cannes and Sundance Award-winning filmSlam , starring acclaimed poet Saul Williams, and produced material on Yoko Ono's recent album Yes, I'm a Witch. Conceived as a reimagining of director D.W. Griffith’s infamously racist 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation, DJ Spooky’s Rebirth of a Nation is a controversial and culturally significant project that examines how “…exploitation and political corruption still haunt the world to this day, but in radically different forms.” Originally commissioned in 2004 by the Lincoln Center Festival, Spoleto Festival USA, Wiener Festwochen, and the Festival d'Automne a Paris, the project was Miller’s first large-scale multimedia performance piece, and has been performed around the world, from the Sydney Festival to the Herod Atticus Amphitheater, more than fifty times. -

Paul D. Miller, Aka DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid: Ice Music (CAE1217)

Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid: Ice Music Collection CAE1217 Introduction/Abstract For his book and exhibition titled Ice Music, Miller worked through music, photographs and film stills from his journeys to the Antarctic and Arctic, along with original artworks, and re-appropriated archival materials, to contemplate humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Materials include graphics from The Books of Ice, copies of four original scores composed by Paul Miller, DVD of Syfy Channel clips, the CD Ice Music, press, photographs, and pieces of personal gear used in the Polar Regions. Biographical Note: Paul D. Miller Paul D. Miller, also known as ‘DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid’, which is his stage name and self constructed persona, is an experimental and electronic hip-hop musician, conceptual artist, and writer. He was born in 1970 in Washington DC but has been based in New York City for many years. He is the son of one of Howard University's former Deans of Law who died when he was only three, and a mother who was in charge of a fabric shop of international repute. Paul Miller then spent the main part of his childhood in Washington DC’s nurturing bohemia. Paul Miller is a Professor at the European Graduate School (EGS) where he teaches Music Mediated Art. DJ Spooky is known amongst other things for his electronic experimentations in music known as both “illbient” and “trip hop.” His first album, Dead Dreamer, was released in 1996 and he has since then released over a dozen albums. Miller, as DJ Spooky, has collaborated with drummer Dave Lombardo of thrash metal band Slayer; singer, songwriter and guitarist Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth; Chuck D of Public Enemy fame; rapper Kool Keith; Towa Tei, formerly of Deee-Lite; Vernon Reid of Living Colour; The Coup; artists Yoko Ono and Shepard Fairey and many others. -

The Future Is History: Hip-Hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity

The Future is History: Hip-hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College From The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by Ian Peddie (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2006). When hip-hop first broke in on the (academic) scene, it was widely hailed as a boldly irreverent embodiment of the postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, a cut-up method which would slice and dice all those old humanistic truisms which, for some reason, seemed to be gathering strength again as the end of the millennium approached. Today, over a decade after the first academic treatments of hip-hop, both the intellectual sheen of postmodernism and the counter-cultural patina of hip-hip seem a bit tarnished, their glimmerings of resistance swallowed whole by the same ubiquitous culture industry which took the rebellion out of rock 'n' roll and locked it away in an I.M. Pei pyramid. There are hazards in being a young art form, always striving for recognition even while rejecting it Ice Cube's famous phrase ‘Fuck the Grammys’ comes to mind but there are still deeper perils in becoming the single most popular form of music in the world, with a media profile that would make even Rupert Murdoch jealous. In an era when pioneers such as KRS-One, Ice-T, and Chuck D are well over forty and hip-hop ditties about thongs and bling bling dominate the malls and airwaves, it's noticeably harder to locate any points of friction between the microphone commandos and the bourgeois masses they once seemed to terrorize with sonic booms pumping out of speaker-loaded jeeps. -

Remixing on the Shoulders of Giants: to DJ Spooky, Everything's Connected - CNN.Com Page 1 of 2

Remixing on the shoulders of giants: To DJ Spooky, everything's connected - CNN.com Page 1 of 2 Remixing on the shoulders of giants: To DJ Spooky, everything's connected - CNN.com By Todd Leopold , CNN 2012-01-28T00:46:49Z CNN.com Paul D. Miller -- DJ Spooky aka That Subliminal Kid -- bridges diverse genres and subjects, creating something new. Editor's note: This is the third in a weekly series on characteristics of creativity. Part 1 looks at Brian Wilson and passion; part 2 is on Jennifer Egan and the success of failure. Next Saturday's piece will focus on roboticist Heather Knight, intelligence and improvisation. (CNN) -- As a living space, Paul D. Miller's Lower Manhattan studio apartment is fairly sparse: futon on the floor, tiny kitchen, couch and a couple chairs, all crammed into a single elongated room overlooking the street. As a repository of information, however, it's something else again. Along the walls there are shelves and shelves of CDs and DVDs and books, a laptop, audiovisual equipment. Media dominates every free space, whether old-school rap CDs or 1970s foreign films or books about art and philosophy. It is the living space as laboratory, the lair of a multimedia scientist, a place for cutting and shaping and retooling bits and bytes and ideas in an effort to bring forth something new. Miller goes by the nom de technologie DJ Spooky, aka That Subliminal Kid -- the latter a moniker borrowed from a William S. Burroughs character. When he isn't in his apartment, he's traveling -- performing in far-flung locales such as Beijing or Ottawa or Weimar (and, sometimes, the East Village or Brooklyn). -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rhythm Science by Paul D. Miller Biography

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Rhythm Science by Paul D. Miller Biography. Paul D. Miller (b. 1970), more famously known by his stage name and self constructed persona “DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid,” is an experimental and electronic hip-hop musician, conceptual artist, and writer. He was born in 1970 in Washington, D.C., but has been based in New York City for many years. He is the son of one of Howard University’s former deans of law who died when he was only three and a mother who was in charge of a fabric shop of international repute. Paul Miller then spent the main part of his childhood in Washington, D.C.’s nurturing bohemia. Paul Miller is a Professor at The European Graduate School / EGS, where he teaches music mediated art. DJ Spooky is known for, amongst other things, his electronic experimentations in music known as both “illbient” and “trip hop.” His first album, Dead Dreamer , was released in 1996, and he has since then released over a dozen albums. He was the first editor of Artbyte: The Magazine of Digital Arts , which has since ceased publication. Miller’s articles have widely been published in magazines and journals, including The Source, The Village Voice, Artforum, Paper Magazine, and Rap Pages, among others. Paul D. Miller studied in Maine at Bowdoin College, where he focused on his interests in philosophy and French literature. His thesis examines Richard Wagner’s theory of Gesamtkunstwerk (the total art work). After all, it is considered today an inaugural work of the contemporary new media revolution. -

Paul D. Miller, Aka DJ Spooky That Subliminal Kid: Ice Music Collection CAE1217

Paul D. Miller, aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid: Ice Music Collection CAE1217 Introduction/Abstract For his book and exhibition titled Ice Music, Miller worked through music, photographs and film stills from his journeys to the Antarctic and Arctic, along with original artworks, and re-appropriated archival materials, to contemplate humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Materials include graphics from The Books of Ice, copies of four original scores composed by Paul Miller, DVD of Syfy Channel clips, the CD Ice Music, press, photographs, and pieces of personal gear used in the Polar Regions. Biographical Note: Paul D. Miller Paul D. Miller, also known as ‘DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid’, which is his stage name and self constructed persona, is an experimental and electronic hip-hop musician, conceptual artist, and writer. He was born in 1970 in Washington DC but has been based in New York City for many years. He is the son of one of Howard University's former Deans of Law who died when he was only three, and a mother who was in charge of a fabric shop of international repute. Paul Miller then spent the main part of his childhood in Washington DC’s nurturing bohemia. Paul Miller is a Professor at the European Graduate School (EGS) where he teaches Music Mediated Art. DJ Spooky is known amongst other things for his electronic experimentations in music known as both “illbient” and “trip hop.” His first album, Dead Dreamer, was released in 1996 and he has since then released over a dozen albums. Miller, as DJ Spooky, has collaborated with drummer Dave Lombardo of thrash metal band Slayer; singer, songwriter and guitarist Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth; Chuck D of Public Enemy fame; rapper Kool Keith; Towa Tei, formerly of Deee-Lite; Vernon Reid of Living Colour; The Coup; artists Yoko Ono and Shepard Fairey and many others. -

Everybody's Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit

Schneiderman, D. (2006). Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit: William S. Burroughs, DJ Danger Mouse, and the Politics of “Grey Tuesday”. Plagiary: Cross‐Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrica‐ tion, and Falsification, 191‐206. Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Lawsuit: William S. Burroughs, DJ Danger Mouse, and the Politics of “Grey Tuesday” Davis Schneiderman E‐mail: [email protected] Abstract persona is replaced by a collaborative ethic that On February 24, 2004, approximately 170 Web makes the audience complicit in the success of the sites hosted a controversial download of DJ Danger “illegal” endeavor. Mouse’s The Grey Album, a “mash” record com- posed of The Beatles’s The White Album and Jay-Z’s The Black Album. Many of the participating Web sites received “cease and desist” letters from EMI Mash-Ups: A Project for Disastrous Success (The Beatles’s record company), yet the so-called “Grey Tuesday” protest resulted in over 100,000 If the 2005 Grammy Awards broadcast was the downloads of the record. While mash tunes are a moment that cacophonous pop‐music “mash‐ relatively recent phenomenon, the issues of owner- ups” were first introduced to grandma in Peoria, ship and aesthetic production raised by “Grey Tues- day” are as old as the notion of the literary “author” the strategy’s commercial(ized) pinnacle may as an autonomous entity, and are complicated by have been the November 2004 CD/DVD release deliberate literary plagiarisms and copyright in- by rapper Jay‐Z and rockers Linkin Park, titled, fringements. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Carl Hancock

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CARL HANCOCK RUX For more information contact: Ben Sterling 917-626-2105 [email protected] GOOD BREAD ALLEY Emily Lichter 413-527-4900 [email protected] Label website: www.thirstyear.com Artist website: www.carlhancockrux.com IN STORES MAY 23 2006 ON THIRSTY EAR RECORDS When Peter Gordon (music producer and president of indie record label, Thirsty Ear) approached writer/recording artist Carl Hancock Rux about doing a full-length album for his Blue Series, Gordon had a concept in mind—contemporary blues. Blues has been showing up a lot of late, especially in the sounds of buzzworthy rock groups such as the White Stripes, the Strokes, Pearls & Brass. While Rux’s critically acclaimed 1999 debut, Rux Revue (Sony/550) and equally lauded sophomore project, 2004’s Apothecary Rx (Giant Step), had incorporated elements of blues (as well as gospel, rock, classical and hip-hop) within his heady brew of eclectic soul, he had never been asked to record a blues record before. “I was afraid (Gordon) meant he wanted me to sound like Howlin’ or something” the 34 year old multi- disciplinary artist admits, “but Gordon was interested in my concept of the blues—something he’d already heard in my voice, and wanted to hear more of in my music. Gordon’s concept was never intended to be taken literally. He’s a conceptual producer, like a contemporary art gallery curator who exhibits artists actively engaging with form. He was inviting me to interact with the blues the same way he’d invited and challenged his other artists (Mathew Shipp, Mike Ladd, Beans, DJ Spooky, among others) to push the envelope of jazz and hip-hop without being self conscious about it.” While the Strokes may have first been introduced to the blues via their parents’ 60s rock records before finding their way to the source of its inspiration, Rux decided to take an opposite approach— garnering his influences not only from the African American tradition the blues was born out of, but from the country, folk, and rock traditions it has influenced over the last one hundred years. -

The Widow Peaks - New York Times

The Widow Peaks - New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2000/09/24/magazine/the-wid... Magazine The Widow Peaks By Amei Wallach Published: September 24, 2000 There comes a moment during the concert when Yoko Ono throws the audience an appraising look over her jumbo blue rimless glasses. She's a woman of 67 -- hard to believe as she strips off a tailored jacket to reveal arms absent of extra flesh and thighs wrapped in tight denim. This is not her crowd. It's not even a crowd that belongs to DJ Spooky or Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth's Pied Piper of experimental rock, up there on stage to give her context. A frumpled dot-com type is reaching for his P.D.A. and muttering, ''I don't think I've ever met a Yoko Ono fan.'' They've come for Stereolab, which is next on the jazz festival bill at Battery Park this summer night. So Yoko takes one look and then she goes for it: the scream, the big one, the yaayaayaah ululating primal scream that wrings her body. DJ Spooky turns that big head of his in its knitted hood and starts paying more attention to her than to his keyboard. She's a madwoman up there, gasping and keening, ''Listen to your heartbeat!'' She's screaming the way she imagined screaming for a composition she conceived in 1961, when she was hosting avant-garde events in her Chambers Street loft and improvising new art forms. She wrote it down, titled it ''Voice Piece for Soprano'' and later published it in her book ''Grapefruit'': ''Scream.