Conference Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cat Show

THE BREEDS WHY DO PEOPLE ACFA recognizes 44 breeds. They are: Abyssinian SHOW CATS? American Curl Longhair American Curl Shorthair • American Shorthair To see how their cats match up to American Wirehair other breeders. Balinese Bengal • To share information. THE Birman Bombay • British Shorthair To educate the public about their Burmese breed, cat care, etc. Chartreux CAT Cornish Rex • To show off their cats. Cymric Devon Rex Egyptian Mau Exotic Shorthair Havana Brown SHOW Highland Fold FOR MORE Himalayan Japanese Bobtail Longhair INFORMATION Japanese Bobtail Shorthair Korat Longhair Exotic ACFA has a great variety of literature Maine Coon Cat you may wish to obtain. These Manx include show rules, bylaws, breed Norwegian Forest Cat standards and a beautiful hardbound Ocicat yearbook called the Parade of Oriental Longhair Royalty. They are available from: Oriental Shorthair Persian ACFA Ragdoll Russian Blue P O Box 1949 Scottish Fold Nixa, MO 65714-1949 Selkirk Rex Longhair Phone: 417-725-1530 Selkirk Rex Shorthair Fax: 417-725-1533 Siamese Siberian Or check our home page: Singapura http://www.acfacat.com Snowshoe Somali Membership in ACFA is open to any Sphynx individual interested in cats. As a Tonkinese Turkish Angora member, you have the right to vote Turkish Van on changes impacting the organization and your breed. AWARDS & RIBBONS WELCOME THE JUDGING Welcome to our cat show! We hope you Each day there will be four or more rings Each cat competes in their class against will enjoy looking at all of the cats we have running concurrently. Each judge acts other cats of the same sex, color and breed. -

Final Copy 2020 09 29 Mania

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Maniaki, Evangelia Title: Risk factors, activity monitoring and quality of life assessment in cats with early degenerative joint disease General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. RISK FACTORS, ACTIVITY MONITORING AND QUALITY OF LIFE ASSESSMENT IN CATS WITH EARLY DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASE Evangelia Maniaki A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Master’s in Research in the Faculty of Health Sciences Bristol Veterinary School, June 2020 Twenty-nine thousand two hundred and eighteen words 1. -

Tyrosinase Mutations Associated with Siamese and Burmese Patterns in the Domestic Cat (Felis Catus)

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.2005.01253.x Tyrosinase mutations associated with Siamese and Burmese patterns in the domestic cat (Felis catus) L. A. Lyons, D. L. Imes, H. C. Rah and R. A. Grahn Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA Summary The Siamese cat has a highly recognized coat colour phenotype that expresses pigment at the extremities of the body, such as the ears, tail and paws. This temperature-sensitive colouration causes a ÔmaskÕ on the face and the phenotype is commonly referred to as ÔpointedÕ. Burmese is an allelic variant that is less temperature-sensitive, producing more pigment throughout the torso than Siamese. Tyrosinase (TYR) mutations have been sus- pected to cause these phenotypes because mutations in TYR are associated with similar phenotypes in other species. Linkage and synteny mapping in the cat has indirectly sup- ported TYR as the causative gene for these feline phenotypes. TYR mutations associated with Siamese and Burmese phenotypes are described herein. Over 200 cats were analysed, representing 12 breeds as well as randomly bred cats. The SNP associated with the Siamese phenotype is an exon 2 G > A transition changing glycine to arginine (G302R). The SNP associated with the Burmese phenotype is an exon 1 G > T transversion changing glycine to tryptophan (G227W). The G302R mutation segregated concordantly within a pedigree of Himalayan (pointed) Persians. All cats that had ÔpointedÕ or the Burmese coat colour phenotype were homozygous for the corresponding mutations, respectively, suggesting that these phenotypes are a result of the identified mutations or unidentified mutations that are in linkage disequilibrium. -

Breeding Policy

ORIENTAL BREEDING POLICY This breeding policy accompanies and supplements the Oriental Registration Policy and should be read in conjunction with that document. The aim of this breeding policy is to give advice and guidance to ensure breeders observe what is considered “best practice” in breeding Orientals with the over-riding objective of improving the Oriental cat to meet all aspects of the Oriental Standard of Points, which describes the ideal for the recognised varieties in the Oriental Group. The origins of the Oriental Until the late 1960’s very few Orientals were seen at shows other than the Havanas (which had their own classes), and the Lilacs and Whites which were exhibited as ‘Any Other Variety (AOV)’. By the end of the decade the Havanas and the Tabby Pointed Siamese (only recognised as a variety of Siamese in 1966), were among the best Siamese types in the country. With the help of prudent outcrossing between Havanas and Tabby Point Siamese, and by backcrossing to both parental varieties, further improvement was made in the Havanas and the emergence of the Oriental Tabby as a beautiful variety in its own right was assured. Hot on the heels of the Oriental Tabbies came the Blues, Blacks, Tortoiseshells (Torties), Silver Tabbies, Smokes and Shaded Silvers. The Oriental is now well established in the UK and over 50 years of breeding has developed and fixed good phenotype in the breed but with a decreasing gene-pool. The Oriental breed has one of the largest numbers of gene variations of any breed of pedigree cat recognised by GCCF. -

Preventing Fading Kitten Syndrome in Hairless Peterbald Cats

Preventing Fading Kitten Syndrome in Hairless Peterbald Cats Mark Kantrowitz 1 Abstract Newborn hairless Peterbald kittens have a very high mortality rate, rarely surviving to one month of age. Since the early days of the breed, breeders have not attempted to breed born-hairless sires and dams together because all of the kittens will be hairless, with few surviving to adulthood. Even in litters from heterozygous parents, it is unusual for more than one hairless kitten to survive. Several potential causes of fading kitten syndrome in Peterbald cats are identified. A new 7-step protocol has been developed to address all of the potential causes of fading kitten syndrome. This protocol has been used successfully to breed a hairless sire, CelestialBlue Eureka, with a hairless dam, CelestialBlue Mimsy. All four hairless kittens in this litter have survived to four months of age, and there is every expectation that they will reach adulthood and live normal lifespans. This is the first time a litter of born-hairless Peterbald kittens has achieved a 0% mortality rate since the origin of the Peterbald breed. Litter of four hairless Peterbald kittens at one month of age 1 CelestialBlue Peterbald Cattery, Peterbald.com Introduction The Peterbald is a rare breed of hairless housecat that originated in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1994. It is the result of a cross of the hairless Donskoy (Don Sphynx) with Oriental Shorthair cats. Siamese cats were subsequently allowed as outcrosses. The result is an intelligent and affectionate hairless cat with a long, elegant, tubular body, large, low-set ears and a triangular head with a blunt tip. -

CFA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING FEBRUARY 4/5, 2017 Index To

CFA EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING FEBRUARY 4/5, 2017 Index to Minutes Secretary’s note: This index is provided only as a courtesy to the readers and is not an official part of the CFA minutes. The numbers shown for each item in the index are keyed to similar numbers shown in the body of the minutes. (1) MEETING CALLED TO ORDER. .................................................................................... 3 (2) ADDITIONS/CORRECTIONS; RATIFICATION OF ON-LINE MOTIONS. ................ 5 (3) APPEAL HEARING. ....................................................................................................... 12 (4) PROTEST COMMITTEE. ............................................................................................... 13 (5) INVESTMENT PRESENTATION. ................................................................................. 14 (6) CENTRAL OFFICE OPERATIONS. .............................................................................. 15 (7) MARKETING................................................................................................................... 18 (8) BOARD CITE. .................................................................................................................. 20 (9) JUDGING PROGRAM. ................................................................................................... 29 (10) REGIONAL ASSIGNMENT ISSUE. .............................................................................. 34 (11) PERSONNEL ISSUES. ................................................................................................... -

TICA Oriental Longhair & Oriental Shorthair Breed Introduction Www

TICA Oriental Longhair & Oriental Shorthair Breed Introduction www.tica.org General Description: The Oriental is a member of the Siamese breed group and comes in two coat lengths: the Oriental Shorthair and the Oriental Longhair. Like all of the group members (Siamese, Balinese, Oriental Shorthairs and Oriental Longhairs), Orientals are long, slender, stylized cats. They are lively, talkative and intelligent and are very attached to their people. All of the members of the breed group have the same physical standard except for coat length and color. What makes the Oriental Shorthair distinct from the rest of the Siamese group is their wide array of colors combined with a short sleek coat while the Oriental Longhair has a semi-long coat draping the elegant body. History : Orientals are a man-made breed that originated in the 1950s in England. After World War II the number of breeders and breeding cats was reduced. Some of the remaining breeders became quite creative as they rebuilt their breeding programs. Many modern breeds developed from the crosses done at that time. One such breed is the Oriental Shorthair/Longhair. Russian Blues, British Shorthairs, Abyssinians, and regular domestic cats were crossed to Siamese. The resulting cats were not pointed and were crossed back to Siamese. In surprisingly few generations, there were cats that were indistinguishable from Siamese in all ways except color. As the Siamese pointed color is genetically recessive, pointed kittens were also produced. The best Siamese-colored cats from these crosses went back into the Siamese breed, enlarging and strengthening the Siamese gene pool. -

Gems System – Gccf Sections & Breeds

GEMS SYSTEM – GCCF SECTIONS & BREEDS SECTIONS & BREEDS HOUSEHOLD PET SECTION PATTERNS NPL Non Pedigree LH/SLH WITH WHITE SECTION 1 NPS Non Pedigree Shorthaired 01 van EXO Exotic PPL Pedigree Pet LH/SLH 02 harlequin (high white) PER Persian PPS Pedigree Pet Shorthaired 03 bicolour5 Household pet GEMS codes are just 04 mitted (RAG only) SECTION 2 one of the above regardless of 05 snowshoe (SNO only) MCO Maine Coon colour(s) or pattern. 09 unspecified white/white NEB Nebelung So for example all shorthaired pedigree spotting gene NFO Norwegian Forest Cat pets have the same GEMS code; PPS. 5 Default for cats “with white” including RAG Ragdoll tortie & white, except NFO (use 09). RGM RagaMuffin NON –RECOGNISED BREEDS SBI (Sacred) Birman XSH Non-Recognised SH SHADED & TIPPED SIB Siberian XLH Non-Recognised LH 11 shaded SOL Somali Longhair 12 tipped 14 with mantle6 SOS Somali Shorthair COLOURS 6 TUV Turkish Van a blue As PER Pewters b chocolate TABBY PATTERNS SECTION 3 c lilac 7 BLH British Longhair d red1 21 unspecified tabby BSH British Shorthair e cream 22 classic/marble/blotched tabby CHA Chartreux em apricot 23 mackerel tabby MAN Manx f black tortie2 24 spotted tabby SRL Selkirk Rex Longhair g blue tortie 25 ticked tabby SRS Selkirk Rex Shorthair h chocolate tortie 28 karpati 7 21 used for all tabby pointed cats or “High j lilac tortie White” cats (01 or 02). Also used for any SECTION 4 k caramel tortie other Tabby cats where the tabby pattern ABY Abyssinian m caramel is not (yet) clear. -

Northwest Regional Awards 2019 – 2020

Northwest Regional Awards 2019 – 2020 Northwest Regional Awards Booklet 2019 – 2020 Summer 2020 2019-20 Northwest Regional Awards Page 2 2019-20 Northwest Regional Awards Page 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgments & Donors Grands of Distinction Page 5 Page 28 Championship Cats Distinguished Merit Page 6 Page 29 Kittens Catteries of Distinction Page 11 Page 30 Premiership Best, Second & Third Best of Breed Page 31 Page 16 Best & Second Best of Color Household Pets Page 21 Page 33 Veterans Grand Champions Page 24 Page 35 Agility Grand Premiers Page 26 Page 36 Grand Household Pets Page 37 2019-20 Northwest Regional Awards Page 4 Acknowledgments & Donors Awards Coordinators Regional Awards - Physical Pam Moser Trophies – Centaur Awards Tammy Roark Rosettes – Centaur Awards Kathy Durdick Awards Distribution Rian MoserAwards Database Pam & Brian Moser Tammy Roark Terri & Dan Zittel Regional Awards - Emails Donations Tammy Roark Puget Sound & McKenzie River Cat Club Seattle Cat Club Sponsorship Coordinators Lewis & Clark Cat Club Tammy Roark North Pacific Siamese Fanciers Kathy Durdick Dee Johnson & Connie Roberts Shirley Rafferty Awards Booklet Wendy Heidt Deena Stevens Awards Treasurer Regional Web Site Kendall Smith Kathy Durdick On the Road Again Deena Stevens 2019-20 Northwest Regional Awards Page 5 Championship Best Cat GC, BWR, NW Wild Rain Huckleberry Br: David-Carol Freels Ow: Carol Freels, David Freels Dee and Connie congratulate the Beautiful Ocicat, Huckleberry and his owners Dave and Carol Freels. Huckleberry had the Best Showmanship -

The Oriental Shorthair and Longhair

The Breed of the Month is… The Oriental Shorthair and Longhair Overview The Oriental belongs to the Oriental Breed Group which includes the Balinese, and the Siamese. All members of this breed group abide by the same standard, except for the hair coat. What separates the Orientals from the rest of this group, is its vast array of coat colors. The Oriental is a striking mix of beauty and intelligence. For some, the Oriental’s sleek body lines, color contrasts, strongly defined heads, almond shaped eyes, and their elegant coats make them a work of art. When combined with a sharp intelligence, a curious personality, along with their loving nature, that is the making of the Oriental. History The Oriental is a man-made breed that was developed in the 1950s in England. After WWII, breeders and breeding cats had been reduced and the remaining breeders experimented with rebuilding their programs. One breed that developed from this experimentation was the Oriental. Creation of the Oriental came from cross breeding the Siamese with a variety of other breeds such as the Russian Blue, British Shorthair, Abyssinian, and regular domestic cats. This resulted in non-pointed cats that were then cross bred back to the Siamese. After a few generations of cross breeding there were cats that where identical to the Siamese in every way aside from the color. These non-pointed cats are the ancestors to the Oriental. Originally each different color was on course to be its own breed. However due to the vast color array possible leading to the potential of hundreds of new breeds, all non- pointed Siamese cats were grouped together into one breed, the Oriental. -

Feline Lower Urinary Tract Disease from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Feline lower urinary tract disease From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD) is a term that is used to cover many problems of the feline urinary tract, including stones and cystitis. The term feline urologic syndrome (FUS) is an older term which is still sometimes used for this condition. The condition can lead to plugged navigation penis syndrome also known as blocked cat syndrome. It is a common disease in adult cats, though it can strike in young cats too. It may Main page present as any of a variety of urinary tract problems, and can lead to a complete blockage of the urinary system, which if left untreated is fatal. Contents FLUTD is not a specific diagnosis in and of itself, rather, it represents an array of problems within one body system. Featured content Current events FLUTD affects cats of both sexes, but tends to be more dangerous in males because they are more susceptible to blockages due to their longer, Random article narrower urethrae. Urinary tract disorders have a high rate of recurrence, and some cats seem to be more susceptible to urinary problems than others. search Contents 1 Symptoms Go Search 2 Causes interaction 3 Treatment About Wikipedia 4 Further reading Community portal 5 External links Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Symptoms [edit] Donate to Wikipedia Help Symptoms of the disease include prolonged squatting and straining during attempts to urinate, frequent trips to the litterbox or a reluctance to leave toolbox the area, small amounts of urine voided in each attempt, blood in the urine, howling, crying, or other vocalizations. -

Spring, 1998.Pub

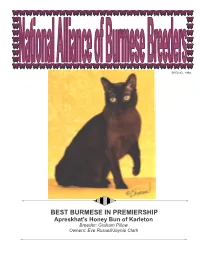

SPRING, 1998 BEST BURMESE IN PREMIERSHIP Apreskhat‘s Honey Bun of Karleton Breeder: Graham Pillow Owners: Eve Russell/Jaynie Clark 1 From the President of NABB . Spring, 1998 Inside this issue . At the February 1998 Board Meeting, the NATIONAL ALLIANCE OF BURMESE President‘s Message - WIAB? 1 BREEDERS, INC. much discussed recommendation of the Treasurer‘s Quarterly Report 2 “What Is A Breed?” (WIAB) Committee was 19971997----9898 Board of Directors adopted by a unanimous vote of the CFA Annual Financial Statement, 1997 2 PRESIDENT - Pat Jacobberger Board of Directors. This recommendation is 2701 Overlook Drive as follows: Notice of Elections - NABB 3 Bloomington, MN 55431 E-mail - [email protected] FAX - 612-888-8311 Winn Feline Foundation Symposium 4 DEFINITION OF A BREED SECRETARY - Michele Clark Feline Genome Project 5 A breed is a group of domestic cats (sub- 1435 N. Allen Avenue species felis catus) that the governing body Pasadena, CA 91104 Chronic Nasal Discharge in the Cat 6 E-mail - [email protected] of CFA has agreed to recognize as such. A Show Business 8 breed must have distinguishing features that TREASURER - Chuck Reich set it apart from all other breeds. 922 Columbia Place Burmese Breed Standards - A 12 Boulder, CO 80303 World-Wide Comparison The definition presumes the following: E-mail - [email protected] Hand-rearing Kittens 14 1. At the time of recognition for DIRECTOR - Erika Graf-Webster registration CFA will assign a new breed 11057 Saffold Way European Burmese 16 into one of four classifications - Reston, VA 22090 Established, Hybrid, Mutation, Natural. E-mail - [email protected] NABB Membership 17 2.