Appendix a How to Get Internet CNN Newsroom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

China's Response to the Global Financial Crisis: Implications For

The Global Business Law Review Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 5 2010 China’s Response to the Global Financial Crisis: Implications for U.S. – China Economic Relations Daniel C.K. Chow The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gblr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the International Trade Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Daniel C.K. Chow, China’s Response to the Global Financial Crisis: Implications for U.S. – China Economic Relations , 1 Global Bus. L. Rev. 47 (2010) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gblr/vol1/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Global Business Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHINA’S RESPONSE TO THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC RELATIONS DANIEL CHOW* ABSTRACT ............................................................................. 48 I. THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS AND ITS EFFECT ON CHINA . 49 A. China’s Export Driven Economy................................... 50 1. Exports as a Percentage of GDP............................. 50 2. China’s Trade Balance with the United States....... 51 a. Lack of Reciprocal Spending By China .......... 54 b. Currency Policies............................................ 56 c. Export Subsidies.............................................. 59 3. Foreign Direct Investment...................................... 60 4. Summary ................................................................ 62 5. Impact of Financial Crisis ...................................... 63 II. CHINA’S RESPONSE TO FINANCIAL CRISIS ............................. 66 A. Political Response......................................................... 68 B. Economic Response....................................................... 71 1. -

Russia and Asia: the Emerging Security Agenda

Russia and Asia The Emerging Security Agenda Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent international institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of arms control and disarmament. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden’s 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed mainly by the Swedish Parliament. The staff and the Governing Board are international. The Institute also has an Advisory Committee as an international consultative body. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Professor Daniel Tarschys, Chairman (Sweden) Dr Oscar Arias Sánchez (Costa Rica) Dr Willem F. van Eekelen (Netherlands) Sir Marrack Goulding (United Kingdom) Dr Catherine Kelleher (United States) Dr Lothar Rühl (Germany) Professor Ronald G. Sutherland (Canada) Dr Abdullah Toukan (Jordan) The Director Director Dr Adam Daniel Rotfeld (Poland) Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Signalistg. 9, S-1769 70 Solna, Sweden Cable: SIPRI Telephone: 46 8/655 97 00 Telefax: 46 8/655 97 33 E-mail: [email protected] Internet URL: http://www.sipri.se Russia and Asia The Emerging Security Agenda Edited by Gennady Chufrin OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1999 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens -

President Trump Said He Could

COVID-19 5/27 UPDATE COVID-19 5/27 Update Global Total cases – 5,644,562 Total deaths – 352,789 United States Total cases – 1,691,342 Total deaths – 99,724 Total # tests – 14,907,041 Administration • President Trump said he could “override” governors who decline to reopen houses of worship in their states in “many different ways,” but did not cite what authority he had to so. o “I can absolutely do it if I want to and I don’t think I’m going to have to because it’s starting to open up,” Trump said Tuesday during a news conference in the White House Rose Garden. o “We need people that are going to be leading us in faith. And we’re opening ‘em up, and if I have to, I will override any governor that wants to play games. If they want to play games, that’s okay, but we will win, and we have many different ways where I can override them,” he continued. o The President also added that "there may be some areas where the pastor or whoever may feel that it’s not quite ready and that’s okay, but let that be the choice of the congregation and the pastor.” • US Citizenship and Immigration Services, the federal agency responsible for visa and asylum processing, is expected to furlough part of its workforce this summer if Congress doesn't provide emergency funding to sustain operations during the coronavirus pandemic. o "Unfortunately, as of now, without congressional intervention, the agency will need to administratively furlough a portion of our employees on approximately July 20," USCIS Deputy Director Joseph Edlow for Policy wrote in a letter sent to the workforce on Tuesday. -

BC Law Magazine Summer 2015 Boston College Law School

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Magazine Summer 7-1-2015 BC Law Magazine Summer 2015 Boston College Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Boston College Law School, "BC Law Magazine Summer 2015" (2015). Boston College Law School Magazine. 46. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclsm/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWSMAKER Justice in Baltimore How Marilyn Mosby ’05 Stunned the Nation POLITICS BOSTON COLLEGE LAW SCHOOL MAGAZINE The Citizen SUMMER 2015 Leon Rodriguez ’88 BC.EDU/BCLAWMAGAZINE Safeguards the American Dream PROFILE Lost and Found The Remarkable Journey of Taisha Sturdivant ’16 THE ODD COUPLE PAUL CALLAN ’75 AND MEL ROBBINS ’94 ARE THE UNLIKELIEST OF PAIRINGS AS TWO OF CNN’S TOP LEGAL ANALYSTS. BUT THEIR ON-AIR FUSION YIELDS SHREWD INSIGHT, CHARISMATIC COMMENTARY, AND TURBO-CHARGED DEBATE BC Law Magazine AGAINST THE ODDS HOW TAISHA STURDIVANT ’16 USED HER WITS TO SURVIVE AND THRIVE. PAGE 38 Photograph by DANA SMITH Contents SUMMER 2015 VOLUME 23 / NUMBER 2 Features 24 It Takes Two Paul Callan ’75 and Mel Robbins ’94 are the unlike- liest of pairings as two of 32 CNN’s top legal analysts but their on-air fusion 68 yields shrewd insight, commentary, and debate. -

Tour Itinerary/Discussion Questions Introduction

STUDENT HANDOUT: TOUR ITINERARY/DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Directions: As you reach each stop on the Inside CNN Tour, try to complete the tasks and answer the questions on this sheet. INTRODUCTION THEATER: Learn about the evolution of a news story from interviews in the field, to satellites far beyond Earth’s atmosphere, to newsrooms and then to televisions and mobile devices everywhere. As you watch the video, track the steps a story takes before you see it in your living room. Identify any terms with which you are unfamiliar. Consider what technologies are used in CNN broadcasts. BIRTH OF CNN: Take a trip back through the evolution of journalism, from cave paintings to the Gutenberg Printing Press to the birth of CNN. As you walk through the hallway to the studio overlook, note the timeline on the evolution of journalism. Consider how each advance in technology and know-how impacted how people at the time learned about their world. When did Ted Turner launch CNN? Why do you think that this announcement was considered so groundbreaking at the time? STUDIO OVERLOOK: Modern studios provide the setting for much of CNN’s acclaimed programming. Learn about the planning and construction of the studios and all of the technical equipment and components used to broadcast news each day. Based on what you see in the time-lapsed video, what goes into putting together a production such as Lou Dobbs Tonight? Look at the timeline along the wall. What are some of the events that CNN has covered since its 1980 launch? How might CNN’s coverage have impacted an event or the course of the event? TELEPROMPTER/CHROMA-KEY: Advances in computer technology have become a vital tool for the modern news network. -

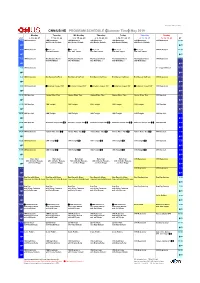

CNN/US HD PROGRAM SCHEDULE (Summer Time) May 2019

latest update:2019/3/20 16:40 CNN/US HD PROGRAM SCHEDULE (Summer Time) May 2019 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday JST 6, 13, 20, 27 7, 14, 21, 28 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 2, 9, 16, 23, 30 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 4, 11, 18, 25 5, 12, 19, 26 ET 4:00 CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom CNN Newsroom 15:00 with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin with Brooke Baldwin :30 :30 5:00 CNN Newsroom ◎The Lead ◎The Lead ◎The Lead ◎The Lead ◎The Lead CNN Newsroom 16:00 with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper with Jake Tapper :30 :30 6:00 CNN Newsroom The Situation Room The Situation Room The Situation Room The Situation Room The Situation Room CNN Newsroom 17:00 with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer with Wolf Blitzer :30 :30 7:00 CNN Newsroom S.E.Cupp Unfiltered 18:00 :30 :30 8:00 CNN Newsroom Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront Erin Burnett OutFront CNN Newsroom 19:00 :30 :30 9:00 CNN Newsroom ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° ◎Anderson Cooper 360° CNN Newsroom 20:00 :30 :30 10:00 CNN Specials Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time Cuomo Prime Time CNN Specials 21:00 :30 :30 11:00 CNN Specials CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Specials 22:00 :30 :30 12:00 CNN Specials CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Tonight CNN Specials -

SITI AMALIAH HASAN.FISIP.Pdf

DIPLOMASI DIGITAL UK TERHADAP MESIR MELALUI MEDIA SOSIAL TWITTER DALAM BIDANG PENDIDIKAN PADA 2014-2018 Skripsi Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.Sos) Oleh: Siti Amaliah Hasan 11161130000023 PROGRAM STUDI HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2021 i PERSETUJUAN PEMBIMBING SKRIPSI Dengan ini, Pembimbing Skripsi menyatakan bahwa mahasiswa: Nama : Siti Amaliah Hasan NIM : 11161130000023 Program Studi : Ilmu Hubungan Internasional telah menyelesaikan penulisan skripsi dengan judul: DIPLOMASI DIGITAL UK TERHADAP MESIR MELALUI MEDIA SOSIAL TWITTER DALAM BIDANG PENDIDIKAN PADA 2014-2018 dan telah memenuhi syarat untuk diuji. Jakarta, 18 Januari 2021 Mengetahui, Menyetujui, Ketua Program Studi Pembimbing M. Adian Firnas, M.Si Irfan R. Hutagalung, LL.M iii PENGESAHAN PANITIA UJIAN SKRIPSI SKRIPSI DIPLOMASI DIGITAL UK TERHADAP MESIR MELALUI MEDIA SOSIAL TWITTER DALAM BIDANG PENDIDIKAN PADA 2014-2018 Oleh Siti Amaliah Hasan 11161130000023 telah dipertahankan dalam sidang ujian skripsi di Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta pada tanggal 1 Februari 2021. Skripsi ini telah diterima sebagai salah satu syarat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.Sos) pada Program Studi Hubungan Internasional. Ketua, Sekretaris, M. Adian Firnas, M.Si Irfan R. Hutagalung, LL.M. Penguji I, Penguji II, Ahmad Alfajri, MA Febri Dirgantara H, MM. Diterima dan dinyatakan memenuhi syarat kelulusan pada tanggal 1 Februari 2021. Ketua Program Studi Ilmu Hubungan Internasional FISIP UIN Jakarta, M. Adian Firnas, M.Si iv ABSTRAK Skripsi ini membahas upaya diplomasi digital United Kingdom (UK) terhadap publik Mesir melalui media sosial twitter terkait bidang pendidikan periode 2014-2018. Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui bagaimana upaya diplomasi yang dilakukan oleh UK terhadap publik Mesir melalui media sosial twitter. -

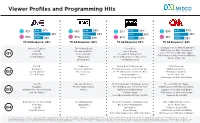

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits

Viewer Profiles and Programming Hits 42% 18-34 27% 55% 18-34 28% 33% 18-34 28% 59% 18-34 34% 35-54 41% 35-54 39% 35-54 43% 35-54 38% 58% 45% 55-65+ 32% 55-65+ 33% 67% 55-65+ 28% 41% 55-65+ 28% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 60% TV Ad Response1 63% TV Ad Response1 64% America’s Top Dog The Walking Dead Below Deck The Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD Two and a Half Men Project Runway CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera State of the Union With Jake Tapper Alaska PD Better Call Saul Below Deck Sailing Yacht Q1 CNN Newsroom With Fredricka Whitfield Live PD: Wanted Talking Dead The Real Housewives of New Jersey Cuomo Prime Time Breaking Bad Vanderpump Rules Live PD Tombstone Below Deck Mediterranean CNN Newsroom Biography Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives of New York City CNN Newsroom Live Q2 Live PD: Wanted Better Call Saul The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Erin Burnett OutFront Live PD: Rewind Movies Vanderpump Rules Cuomo Prime Time Below Deck Sailing Yacht CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera Live PD Two and a Half Men The Real Housewives Of Orange County The Lead With Jake Tapper Biography Fear the Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin Q3 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On Movies Below Deck Mediterranean Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Live PD: Wanted Southern Charm CNN Newsroom With Ana Cabrera The Real Housewives Of New York City Anderson Cooper 360 Garth Brooks: The Road I’m On The Walking Dead The Real Housewives of Orange County CNN Tonight With Don Lemon Court Cam Talking Dead Below Deck Mediterranean Cuomo Prime Time Q4 Live PD Movies Below Deck Anderson Cooper 360 Live PD: Wanted Project Runway Situation Room With Wolf Blitzer Watch What Happens Live With Andy Cohen CNN Newsroom With Brooke Baldwin 1 Percentage of network viewers that have seen/heard a TV ad in the last 12 months that has led them to take action as defined as clicking on a banner ad, doing an internet search, going to the advertisers website, buying the product advertised or calling/visiting the advertiser. -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022. -

Revising Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

Politics, Practice and Pacifism: Revising Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution Michael A. Panton* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 164 Part I ...................................................................................................... 167 II. THE HISTORICAL ORIGINS OF ARTICLE 9 .......................................... 167 A. The Realities of War .................................................................. 169 III. U.S. FOREIGN POLICY IN ASIA AFTER WWII .................................... 173 A. The Soviet Union, China, and the Cold War ............................ 173 B. Korea: Ideological showdown at the Thirty-eighth Parallel .... 177 IV. THE PARADOX OF ARTICLE 9 ............................................................ 178 Part II ..................................................................................................... 182 V. ATTEMPTS AT CONSTITUTION REFORM AND THE POLITICAL FALLOUT182 VI. OF POLITICS, PRACTICE, AND PACIFISM: THE PUBLIC DEBATE ......... 189 A. In Support of Reform ................................................................ 191 1. The Limits of American Resources and the Question of Commitment to Japan and the Region .............................. 191 2. Security Alliances and the ongoing Reinterpretation of Article 9 ............................................................................. 194 3. Ultra-Nationalism .............................................................. 196 4. Regional Fears .................................................................. -

International Law from a Machiavellian Perspective Anthony D'amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected]

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2010 International Law from a Machiavellian Perspective Anthony D'Amato Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation D'Amato, Anthony, "International Law from a Machiavellian Perspective" (2010). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 92. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/92 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. International Law from a Machiavellian Perspective, by Anthony D'Amato, pp.82-95, in The Realist Tradition and Contemporary International Relations, ed. by W. David Clinton, (Political Traditions in Foreign Policy series), Louisiana State University Press, 2007 Abstract: Machiavelli leaves one with both an optimistic and a pessimistic prognostication for the post-Cold War world. On the one hand, the end of that conflict has opened the way for the spread of liberal, constitutional regimes, which he would say are inclined to be more and more meticulous in honoring their commitments. On the other, the temptation to use force to create new facts and thereby force international law into new paths will remain as long as politics is practiced. The contemporary relevance of Machiavelli may be seen in that he urged both realities upon us. I focus on a single incident that postdated the end of the Cold War—the show of force by the People's Republic of China (PRC) in the Taiwan Strait in March 1996.