J. C. Okyere's Bequest of Concrete Statuary in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections October 6, 2013 - March 2, 2014

Updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 | 1:38:43 PM Last updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 Updated Tuesday, December 31, 2013 | 1:38:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections October 6, 2013 - March 2, 2014 To order publicity images: Publicity images are available only for those objects accompanied by a thumbnail image below. Please email [email protected] or fax (202) 789-3044 and designate your desired images, using the “File Name” on this list. Please include your name and contact information, press affiliation, deadline for receiving images, the date of publication, and a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned. Links to download the digital image files will be sent via e-mail. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. Cat. No. 1A / File Name: 3514-117.jpg Statuette of Europa, 1st or early 2nd century marble height: 34.5 cm (13 9/16 in.) Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth Cat. No. 1B / File Name: 3514-118.jpg Head of Pan, 2nd century (?) marble height: 14.4 cm (5 11/16 in.) Archaeological Museum of Ancient Corinth Cat. -

University Regulations Handbook

1. GENERAL INFORMATION ON UNIVERSITY OF GHANA Postal Address - P. O. Box LG 25, Legon, Ghana Fax - (233-302) 500383/502701 Telephone - (233-302) 500381/500194/502255/502257/ 502258/500430/500306/514552 E-mail - [email protected] [email protected] Overseas Address - The Overseas Representative Universities of Ghana Office 321 City Road, London, ECIV ILJ, England Tel: 44 (0) 207-2787-413 Fax: 44 (0) 2077-135-776 E-mail:[email protected] Language of Instruction - English 1 UNIVERSITY OFFICERS PRINCIPAL OFFICERS Chancellor - H. E. Kofi Annan Chairman, University Council - Professor Yaw Twumasi Vice-Chancellor - Professor Ebenezer Oduro Owusu OTHER OFFICERS Pro-Vice-Chancellor - Professor Samuel K. Offei (Academic and Student Affairs) Pro-Vice-Chancellor - Professor Francis N. A. Dodoo (Research Innovation and Development) Registrar - Mrs. Mercy Haizel Ashia University Librarian - Professor Perpetua Sakyiwa Dadzie PROVOSTS College of Basic and Applied Sciences - Professor Daniel K. Asiedu College of Education - Professor Michael Tagoe (Acting) College of Health Sciences - Professor Patrick F. Ayeh-Kumi College of Humanities - Professor Samuel Agyei-Mensah DEANS Student Affairs - Professor Francis K. Nunoo International Programmes - Professor Ama De-Graft Aikins School of Graduate Studies - Professor Kwaku Tano-Debrah College of Basic & Applied Sciences School of Agriculture - Professor Daniel B. Sarpong School of Biological Sciences - Professor Matilda Steiner-Asiedu School of Engineering Sciences - Professor Boateng Onwuona-Agyemang School of Physical -

Ebook Download Greek Art 1St Edition

GREEK ART 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nigel Spivey | 9780714833682 | | | | | Greek Art 1st edition PDF Book No Date pp. Fresco of an ancient Macedonian soldier thorakitai wearing chainmail armor and bearing a thureos shield, 3rd century BC. This work is a splendid survey of all the significant artistic monuments of the Greek world that have come down to us. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. Inscription to ffep, else clean and bright, inside and out. The Erechtheum , next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. Well into the 19th century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the western world. The Moschophoros or calf-bearer, c. Red-figure vases slowly replaced the black-figure style. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus , can be seen in Turkey , at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum. The Distaff Side: Representing…. Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World. The Greeks were quick to challenge Publishers, New York He and other potters around his time began to introduce very stylised silhouette figures of humans and animals, especially horses. Add to Basket Used Hardcover Condition: g to vg. The paint was frequently limited to parts depicting clothing, hair, and so on, with the skin left in the natural color of the stone or bronze, but it could also cover sculptures in their totality; female skin in marble tended to be uncoloured, while male skin might be a light brown. After about BC, figures, such as these, both male and female, wore the so-called archaic smile. -

J. B. Danquah Was Never Chief Campaigner Or Founder of University of Ghana

J. B. Danquah was Never Chief Campaigner or Founder of University of Ghana By: Prof N. Lungu Prof. Kwame Botwe-Asamoah Prof. Kofi Kissi Dompere (Cite as: Lungu, Botwe-Asamoah, & Dompere, 2019) “In writing this article, we utilized more than one source to establish the history of the founding of the University College of the Gold Coast for all to see. Pioneering advocates for a British West-African University go back to the late 1800s. Then we have, in the Gold Coast, J. E. Casely Hayford, Sir Arku Korsah, Dr. Nanka-Bruce, significant professional groups, and the collective Gold Coast citizenry, some of which worked harder towards the establishment of the University of Ghana, compared to Dr. J. B. Danquah. Therefore, the dastardly plan to assign unjust and unearned historical dividends to a vastly over-rated second-tier supporter of that agenda will never work. That is the objective verdict and responsibility of scholarship, intellectual honesty, and freedom of thought. Dr. J. B. Danquah did not play the role of chief campaigner, primary negotiator, or chief spokesperson, and even less, found the University College of the Gold Coast,” (Lungu, Botwe-Asamoah, & Dompere, 30 June, 2019). Introduction: President Akufo Addo’s assertion during the launching of the “University of Ghana’s Endowment” on 7th May 2018 that “it was the inestimable work of Dr. J. B. Danquah that mobilized the Ghanaian people to insist on the building” of the University of Ghana is grossly misleading if we must be 1 charitable. It is a brazen attempt to re-cast Ghanaian historical facts. -

From Boston to Rome: Reflections on Returning Antiquities David Gill* and Christopher Chippindale**

International Journal of Cultural Property (2006) 13:311–331. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2006 International Cultural Property Society DOI: 10.1017/S0940739106060206 From Boston to Rome: Reflections on Returning Antiquities David Gill* and Christopher Chippindale** Abstract: The return of 13 classical antiquities from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) to Italy provides a glimpse into a major museum’s acquisition patterns from 1971 to 1999. Evidence emerging during the trial of Marion True and Robert E. Hecht Jr. in Rome is allowing the Italian authorities to identify antiquities that have been removed from their archaeological contexts by illicit digging. Key dealers and galleries are identified, and with them other objects that have followed the same route. The fabrication of old collections to hide the recent surfacing of antiquities is also explored. In October 2006 the MFA agreed to return to Italy a series of 13 antiquities (Ap- pendix). These included Attic, Apulian, and Lucanian pottery as well as a Roman portrait of Sabina and a Roman relief fragment.1 This return is forming a pattern as other museums in North America are invited to deaccession antiquities that are claimed to have been illegally removed from Italy. The evidence that the pieces were acquired in a less than transparent way is beginning to emerge. For example, a Polaroid photograph of the portrait of Sabina (Appendix no. 1) was seized in the raid on the warehousing facility of Giacomo Medici in the Geneva Freeport.2 Polaroids of two Apulian pots, an amphora (no. 9) and a loutrophoros (no. 11), were also seized.3 As other photographic and documentary evidence emerges dur- ing the ongoing legal case against Marion True and Robert E. -

Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament

VOLUME: 4 WINTER, 2004 Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture Review by Nancy H. Ramage 1) is a copy of a vase that belonged to Ithaca College Hamilton, painted in Wedgwood’s “encaustic” technique that imitated red-figure with red, An unusual and worthwhile exhibit on the orange, and white painted on top of the “black passion for vases in the 18th century has been basalt” body, as he called it. But here, assembled at the Bard Graduate Center in Wedgwood’s artist has taken all the figures New York City. The show, entitled that encircle the entire vessel on the original, Vasemania: Neoclassical Form and and put them on the front of the pot, just as Ornament: Selections from The Metropolitan they appear in a plate in Hamilton’s first vol- Museum of Art, was curated by a group of ume in the publication of his first collection, graduate students, together with Stefanie sold to the British Museum in 1772. On the Walker at Bard and William Rieder at the Met. original Greek pot, the last two figures on the It aims to set out the different kinds of taste — left and right goût grec, goût étrusque, goût empire — that sides were Fig. 1 Wedgwood Hydria, developed over a period of decades across painted on the Etruria Works, Staffordshire, Britain, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany. back of the ves- ca. 1780. Black basalt with “encaustic” painting. The at the Bard Graduate Center. -

NKRUMAH, Kwame

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Manuscript Division Finding Aids Finding Aids 10-1-2015 NKRUMAH, Kwame MSRC Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu Recommended Citation Staff, MSRC, "NKRUMAH, Kwame" (2015). Manuscript Division Finding Aids. 149. https://dh.howard.edu/finaid_manu/149 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Manuscript Division Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Kwame Nkrumah 1909 September 21 Born to Kobina Nkrumah and Kweku Nyaniba in Nkroful, Gold Coast 1930 Completed four year teachers' course at Achimota College, Accra 1930-1935 Taught at Catholic schools in the Gold Coast 1939 Received B.A. degree in economics and sociology from Lincoln University, Oxford, Pennsylvania. Served as President of the African Students' Association of America and Canada while enrolled 1939-1943 Taught history and African languages at Lincoln University 1942 Received S.T.B. [Bachelor of Theology degree] from Lincoln Theological Seminary 1942 Received M.S. degree in Education from the University of Pennsylvania 1943 Received A.M. degree in Philosophy from the University of Pennsylvania 1945-1947 Lived in London. Attended London School of Economics for one semester. Became active in pan-Africanist politics 1947 Returned to Gold Coast and became General Secretary of the United Gold Coast Convention 1949 Founded the Convention Peoples' Party (C.P.P.) 2 1949 Publication of What I Mean by Positive Action 1950-1951 Imprisoned on charge of sedition and of fomenting an illegal general strike 1951 February Elected Leader of Government Business of the Gold Coast 1951 Awarded Honorary LL.D. -

Leon & Melite's House

The book Leon and Melite: Daily life in ancient Athens is associated with the permanent exhibition Daily life in Antiquity , presented on the 4th floor of the Museum of Cycladic Art. The design of the exhibition and the production of the audiovisual material were carried out by the Spanish company GPD Exposiciones y Museos. The academic documentation and the curating of the exhibition were by the Director of the museum, Professor Nikos Stampolidis, and the museum curator Yorgos Tasoulas to whom we would like to express our warm thanks for his invaluable help and support in the creation of the educational programme. Leon and Melite, brother and sister, grow up in a wealthy Athenian family in the 5th century BC. Young Leon gives us a guided tour of his city. He tells us about his parents’ wedding, as they had described it to him. Then he talks about the daily work of women, tells us about his friends and his sister’s friends and their favourite games, about school, athletics and military training. He describes dinner parties, the symposia , and how men take part in public affairs and, finally, says a few things about burial practices, concentrating on how people honoured their loved ones who had departed this life. The illustrations include reconstruction drawings and objects on display on the 4th floor of the Museum, most of which date from the Classical and Hellenistic periods (5th-1st century BC). Leon & Melite Daily life in ancient Athens Leon & Melite’s house My name is Leon. I was born and brought up in Athens, the most famous city in ancient Greece. -

CYCLADIC ART Athens – Andros

Your Trusted Experts to Greece 248, Oakland Park Ave. | Columbus, OH 43214 Toll Free: 888.GREECE.8 | Fax +30.210.262.4041 [email protected] www.DestinationGreece.com CYCLADIC ART Athens – Andros - Tinos formation of the modern state of G reece (1830) (9 Days / 8 N ights) dow n to 1922, the year in w hich the Asia Minor disaster took place Day 1: Athens Arrival Day 3: Athens – Acropolis and the Acropolis Upon arrival at Athens International Airport the M useum Destination G reece representative w ill w elcome you Enjoy breakfast and then start on a journey in the and escort you to your hotel ancient past of G reece. W e visit the most important sites of the city and the pinnacle of the ancient Day 2: Athens – Cycladic Art and Benaki M useum s G reek state of Athens, the Acropolis and Parthenon. After breakfast w e start w ith Conclude the day w ith a visit to the unique, w orld- a visit to the Museum of know n, Museum of Acropolis Cycladic Art (MCA). The Museum of Cycladic Art is Day 4: Athens – Island of Andros dedicated to the study and Morning transfer to the port of Rafina to embark the promotion of ancient cultures ferry boat for the 2-hour voyage to the island of of the Aegean and Cyprus, Andros. Arrival w ith special emphasis on in Andros and Cycladic Art of the 3rd transfer to millennium BC. Chora to visit the G oulandri It w as founded in 1986, to Museum of house the collection of Contemporary N icholas and Dolly Art. -

Cycladic Art & Culture

Hellenic International Studies in the Arts (HISA) Syllabus Course Title: Cycladic Art & Culture Course Code: ARTH 320 / SOCL 320 Credit Hours: 3 Location: Classroom 1, Main building Instructor: Ioanni Georganas and/or Barry Tagrin Telephone: XXXXXXXX Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Office Hour: by appointment Office location: by appointment Syllabus Course Description: This course investigates Greek (mainly Cycladic) art and culture in the form of archeological sites, artistic developments, architecture, mythology, literature, human history, folk traditions, cultural landscapes, and encounters within Greek communities. Course Details: In an attempt to deepen students' understanding and appreciation of the rich cultural history of the Greek world where they are spending the semester, visits are made to important Cycladic island sites and museums, where appropriate. For each excursion, there is a pre-visit preparation by a teacher or contributing guest lecturer in order that participants can receive the maximum benefit from their visit. Primary emphasis is given to myth, archaeology, history, event and classical religious traditions within the context of Greek, Western, and global history rather than art history per se. Temple sites of the gods and goddesses are predominant, but visits include archaeological sites, marble quarries, and museums that showcase ancient sculpture, jewelry, artifacts, as well as later Byzantine and Venetian times. Students who will be augmenting their art and cultural immersion with creative work of their own will have the HISA art studio available for their use, and access to HISA core teaching staff in those areas for small group or one-on-one guidance. Course Objectives: *The course will attempt to deepen students’ understanding and appreciation of the rich cultural history of the Greek world, including its major periods, major forms of Greek art, and Greece’s development and diversification. -

AP Art History Chapter 4 Questions: Aegean Mrs

AP Art History Chapter 4 Questions: Aegean Mrs. Cook Key Terms: • Linear A/Linear B • labyrinth, citadel, cyclopean masonry, megaron, relieving triangle, post and lintel, corbelled arch, tholos, dome, dromos • true/wet fresco, Kamares Ware, faience, chryselephantine sculpture, relief sculpture, niello, repoussé Ideas/Concepts: 1. What are the basic differences between the cultures of Crete (Minoan) and mainland Greece Mycenaean 2. Compare and contrast Minoan and Mycenaean architecture (i.e. Palace of Knossos and the Citadel of Mycenaea.) 3. Why did the Mycenaean culture appropriate Minoan artifacts/images? 4. What is the role of women in religion/as goddess in Minoan culture? 5. How is abstraction/stylization used in Cycladic art and Karmares pottery? 6. What accounts for the difference in appearance (and content) of Minoan art (esp. frescos) in contrast to other ancient cultures (esp. the Egyptians)? Exercises for Study: 1. Enter the approximate dates for these periods: Early Cycladic: Minoan art: Mycenaean art: 2. Summarize the significant historical events and artistic developments of the prehistoric Aegean. 3. Compare and contrast the following pairs of artworks, using the points of comparison as a guide. A. Lion Gate, Mycenae, Greece, ca. 1300‐1250 BCE (Fig. 4‐19); Harvesters Vase, from Hagia Triada (Crete), Greece, ca. 1500‐1450 BCE (Fig. 4‐14); o Periods o Medium, materials & techniques o Subjects o Stylistic features & composition o Function B. Figurine of a woman, from Syros (Cyclades), Greece, ca. 2600‐2300 BCE (Fig. 4‐2); Female head, from Mycenae, Greece, ca. 1300‐1250 BCE o Periods o Medium, materials & techniques o Scale o Subjects o Stylistic features & composition o Probable function C. -

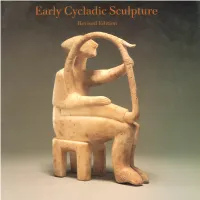

Early Cycladic Sculpture: an Introduction: Revised Edition

Early Cycladic Sculpture Early Cycladic Sculpture An Introduction Revised Edition Pat Getz-Preziosi The J. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California © 1994 The J. Paul Getty Museum Cover: Early Spedos variety style 17985 Pacific Coast Highway harp player. Malibu, The J. Paul Malibu, California 90265-5799 Getty Museum 85.AA.103. See also plate ivb, figures 24, 25, 79. At the J. Paul Getty Museum: Christopher Hudson, Publisher Frontispiece: Female folded-arm Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor figure. Late Spedos/Dokathismata variety. A somewhat atypical work of the Schuster Master. EC II. Library of Congress Combining elegantly controlled Cataloging-in-Publication Data curving elements with a sharp angularity and tautness of line, the Getz-Preziosi, Pat. concept is one of boldness tem Early Cycladic sculpture : an introduction / pered by delicacy and precision. Pat Getz-Preziosi.—Rev. ed. Malibu, The J. Paul Getty Museum Includes bibliographical references. 90.AA.114. Pres. L. 40.6 cm. ISBN 0-89236-220-0 I. Sculpture, Cycladic. I. J. P. Getty Museum. II. Title. NB130.C78G4 1994 730 '.0939 '15-dc20 94-16753 CIP Contents vii Foreword x Preface xi Preface to First Edition 1 Introduction 6 Color Plates 17 The Stone Vases 18 The Figurative Sculpture 51 The Formulaic Tradition 59 The Individual Sculptor 64 The Karlsruhe/Woodner Master 66 The Goulandris Master 71 The Ashmolean Master 78 The Distribution of the Figures 79 Beyond the Cyclades 83 Major Collections of Early Cycladic Sculpture 84 Selected Bibliography 86 Photo Credits This page intentionally left blank Foreword The remarkable stone sculptures pro Richmond, Virginia, Fort Worth, duced in the Cyclades during the third Texas, and San Francisco, in 1987- millennium B.C.