Prussian Blue Sarah Lowengard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boosting the Activity of Prussian-Blue Analogue As Efficient Electrocatalyst

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Boosting the activity of Prussian- blue analogue as efcient electrocatalyst for water and urea oxidation Yongqiang Feng 1*, Xiao Wang1, Peipei Dong1, Jie Li2, Li Feng1, Jianfeng Huang1*, Liyun Cao1, Liangliang Feng1, Koji Kajiyoshi3 & Chunru Wang 2* The design and fabrication of intricate hollow architectures as cost-efective and dual-function electrocatalyst for water and urea electrolysis is of vital importance to the energy and environment issues. Herein, a facile solvothermal strategy for construction of Prussian-blue analogue (PBA) hollow cages with an open framework was developed. The as-obtained CoFe and NiFe hollow cages (CFHC and NFHC) can be directly utilized as electrocatalysts towards oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and urea oxidation reaction (UOR) with superior catalytic performance (lower electrolysis potential, faster reaction kinetics and long-term durability) compared to their parent solid precursors (CFC and NFC) and even the commercial noble metal-based catalyst. Impressively, to drive a current density of 10 mA cm−2 in alkaline solution, the CFHC catalyst required an overpotential of merely 330 mV, 21.99% lower than that of the solid CFC precursor (423 mV) at the same condition. Meanwhile, the NFHC catalyst could deliver a current density as high as 100 mA cm−2 for the urea oxidation electrolysis at a potential of only 1.40 V, 24.32% lower than that of the solid NFC precursor (1.85 V). This work provides a new platform to construct intricate hollow structures as promising nano-materials for the application in energy conversion and storage. Hydrogen energy has been considered as one of the most promising alternatives to traditional fossil fuels such as coal and oil which have inevitably involved in the tough environmental and unsustainable energetic issues1,2. -

Pale Intrusions Into Blue: the Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Pale Intrusions into Blue: The Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE PALE INTRUSIONS INTO BLUE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A COLOR By HANNAH ROSE MENDOZA A Thesis submitted to the Department of Interior Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Hannah Rose Mendoza defended on October 21, 2004. _________________________ Lisa Waxman Professor Directing Thesis _________________________ Peter Munton Committee Member _________________________ Ricardo Navarro Committee Member Approved: ______________________________________ Eric Wiedegreen, Chair, Department of Interior Design ______________________________________ Sally Mcrorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts & Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Pepe, te amo y gracias. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my gratitude to Lisa Waxman for her unflagging enthusiasm and sharp attention to detail. I also wish to thank the other members of my committee, Peter Munton and Rick Navarro for taking the time to read my thesis and offer a very helpful critique. I want to acknowledge the support received from my Mom and Dad, whose faith in me helped me get through this. Finally, I want to thank my son Jack, who despite being born as my thesis was nearing completion, saw fit to spit up on the manuscript only once. -

A New Evaluation of the Colors of the Sky for Artists and Designers

Sky Blue, But What Blue? A New Evaluation of the Colors of the Sky for Artists and Designers Ken Smith* Faculty of Art and Design, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Received 28 April 2006; accepted 21 June 2006 Abstract: This study describes a process of relating the solid that is capable of representing most of the colors of perceptual analysis of the colors of the terrestrial atmos- the sky using four of these pigments is proposed. phere to currently available pigments used in artists’ painting systems. This process sought to discover how the colors of the sky could be defined and simulated by these AN EMPIRICAL METHOD FOR ANALYZING pigments. The author also describes how confusion over SKY COLOR the bewildering choice of suitable pigments on offer in the market place can be clarified. Ó 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Science can explain why the earth’s atmosphere appears Inc. Col Res Appl, 32, 249 – 255, 2007; Published online in Wiley Inter- blue, the preferential scattering by air molecules of short 2 Science (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002/col.20291 wavelength light photons emitted from the sun. For artists the consequential questions are often more likely to Key words: art; design; sky color; perceived color; envi- be not why, but rather what; what are the blue colors that ronment; pigments; painting systems are perceived in the sky? These were the fundamental questions that lead to a reappraisal of how the colors of the sky can be represented by the pigments used in con- INTRODUCTION temporary painting systems. Before attempting to answer this question, a number of parameters had to be created. -

The Color and Electronic Configurations of Prussian Blue

Created by Erica Gunn at Simmons College ([email protected]) and posted on VIPEr (www.ionicviper.org ) on 1/5/15. Copyright Erica Gunn 2015. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike License. To view a copy of this license visit http://creativecommons.org/about/license/ . The Color and Electronic Configurations of Prussian Blue Read the paper cited below and answer the discussion questions before class on _______ . Robin, M.L. The Color and Electronic Configurations of Prussian Blue. Inorganic Chemistry, 1, 1962, pp 337-342. DOI: 10.1021/ic50002a028 Discussion Questions: II III III 1. The authors mention that Prussian Blue, [K,Fe ,Fe ](CN) 6, can be synthesized from either Fe (ClO 4)3 II II III and K 4Fe (CN) 6 or from Fe (ClO 4)2 and K 3Fe (CN) 6. They also report the results of base hydrolysis of Prussian Blue. What do these two experiments tell us about the structure of the pigment, and why is this significant? 2. Draw the crystal field splitting diagram for high and low spin versions of Fe II and Fe III ions that have an octahedral coordination geometry. The paper states that there are two types of iron ion in the crystal structure of Prussian Blue. What is the difference between them? Which do you expect to have the larger ∆oct , based on what you know about the spectrochemical series? 3. How do the authors use the distinction between allowed and forbidden transitions to confirm the identity of Prussian Blue as ferric ferrocyanide? 4. -

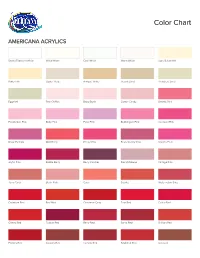

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Scientific Dating of Paintingsdr. Nicholas

Scientific dating Dr. Nicholas of paintings Eastaugh 30 ISSUE 1 MARCH 2006 Scientific dating of paintings is used by a wide range of related fields to provide independent means of verification. This paper outlines the principle approaches that are used, some problems with current methodology, and a potential solution through the application of simple mathematical modelling to the occurrences of materials and techniques in paintings. Offering a means of determining likelihood, this approach also opens up the possibility of studying economic factors involved in use and disuse of historical pigments. t the present time science has no reliable This paper discusses this current methodology, and accurate means for the absolute outlines the basic thinking behind it and the mode Adating of a painting. Calendrical methods of application.We will then examine the validity of such as the familiar radiocarbon dating, or likewise some of its assumptions and show that a major dendrochronology (‘tree-ring dating’)1 are element – that of ‘terminal’ dates for pigments – is unsuitable. Instead, much of the scientific work flawed, and needs replacing by a better concept; determining dates of paintings takes a sideways one describing rates of growth and decline of use. approach, relying on the identification of key We will also see how this naturally leads to new pigments or techniques whose dates of ways of studying the economic history of pigments. introduction or disuse are known. For example, a However first, since we are going to use Prussian painting that looks like a Rembrandt can’t be by blue – iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II) – as a major him if it contains the pigment Prussian blue, example, we need some background on its because that compound wasn’t available until well discovery. -

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended Color

Watercolor Substitution Cheat Sheet * = Lindsay Recommended color *Phthalo Blue (Strong cool-green leaning-blue) Prussian Blue (also look for that pigment) AKA Pthalo blue GS Cyan Blue or green shade. Cerulean Blue (if it looks dark: Mission Gold) Helio Cerulean **This colors is great for mixing green when Winsor Blue (Winsor & Newton) paired with a cool yellow. Intense Blue (Winsor & Newton/Cotman) Azure (Yarka/White Nights) Turquoise Indigo (deep cool blue grey) Indanthrone Blue Payne's Grey+Prussian Blue *Ultramarine Blue (warm, purple bias red) Colbalt Blue Pthalo blue Red Shade (not my fave substitute) **This color is good for mixing violet with a cool Poland Blue red or gray with burnt sienna. ***This color granulates for textured washes. Cerulean Blue (Less intense cool blue) Manganese Blue Phthalo blue + white Cinerous Blue (Sennelier) *Quinacridone Rose (Cool red with violet Alizarian Crimson undertones) Carmine **This color makes lovely purples and mauve Crimson lake with blues. Rose Madder (weaker than AZ) *Cadmium Red or Cadmium red light Vermilion (Warm red with orange undertones) Scarlet Napthol Red **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed Bright Red/ Brilliant Red with warm yellows. Pyrrole Red Permanent Rose Magenta *Cadmium Yellow (warm yellow) Gamboge Cadmium yellow medium/Cadmium yellow deep Indian Yellow Permanent yellow deep **This color makes beautiful oranges when mixed with warm reds or peach with cool reds *Hansa Yellow Light (cool yellow) Lemon Yellow (cool yellow) Cadmium yellow light, pale or Cadmium -

Paul to Sam Winter, 1941 Tuesday Paul Sargent

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Letters and Correspondence Paul Turner Sargent Winter 1941 Paul to Sam Winter, 1941 Tuesday Paul Sargent Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/paul_sargent_letters Recommended Citation Sargent, Paul, "Paul to Sam Winter, 1941 Tuesday" (1941). Letters and Correspondence. 33. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/paul_sargent_letters/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Paul Turner Sargent at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Letters and Correspondence by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. P to S Winter, 1941 Tuesday Dear Sam, Got your letter today and will answer before I lay it aside and forget a week or so. You can believe it or not but we are not bothered with frozen roads this winter, it is an exceptional night when it is cold enough to freeze ice. Last night the fire went out and this morning was not cold enough to need one. What do you know about that near the middle of January. Had big rain last night, much colder predicted for today with snow, but today has been sunny and warm. You asked about painting. You did not mention size of canvas you priced in store. The cheapest way for you is to work on Masonite board. It is substantial and good, and has a canvas grain already on one side. If you can find a planning mill out there, you can probably find the board there also. Have it sawed by them in size you want. -

2Bbb2c8a13987b0491d70b96f7

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS’ FORBES PIGMENT COLLECTION Yoko Ono “If people want to make war they should make a colour war, and paint each others’ cities up in the night in pinks and greens.” Foreword p.6 Introduction p.12 Red p.28 Orange p.54 Yellow p.70 Green p.86 Blue p.108 Purple p.132 Brown p.150 Black p.162 White p.178 Metallic p.190 Appendix p.204 8 AN ATLAS OF RARE & FAMILIAR COLOUR FOREWORD 9 You can see Harvard University’s Forbes Pigment Collection from far below. It shimmers like an art display in its own right, facing in towards Foreword the glass central courtyard in Renzo Piano’s wonderful 2014 extension to the Harvard Art Museums. The collection seems, somehow, suspended within the sky. From the public galleries it is tantalising, almost intoxicating, to see the glass-fronted cases full of their bright bottles up there in the administra- tive area of the museum. The shelves are arranged mostly by hue; the blues are graded in ombre effect from deepest midnight to the fading in- digo of favourite jeans, with startling, pleasing juxtapositions of turquoise (flasks of lightest green malachite; summer sky-coloured copper carbon- ate and swimming pool verdigris) next to navy, next to something that was once blue and is now simply, chalk. A few feet along, the bright alizarin crimsons slake to brownish brazil wood upon one side, and blush to madder pink the other. This curious chromatic ordering makes the whole collection look like an installation exploring the very nature of painting. -

Prussian Blue

FACT SHEET Prussian blue Facts About Prussian blue Prussian blue can remove certain radioactive materials from people’s bodies, but must be taken under the guidance of a doctor. People may become internally contaminated (http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/contamination.asp) (inside their bodies) with radioactive materials by accidentally ingesting (eating or drinking) or inhaling (breathing) them, or through direct contact (open wounds). The sooner these materials are removed from the body, the fewer and less severe the health effects of the contamination will be. Prussian blue is a substance that can help remove certain radioactive materials from people’s bodies. However, small amounts of contamination may not require treatment. Doctors can prescribe Prussian blue if they determine that a person who is internally contaminated would benefit from treatment. What Prussian blue is Prussian blue was first produced as a blue dye in 1704 and has been used by artists and manufacturers ever since. It got its name from its use as a dye for Prussian military uniforms. Prussian blue dye and paint are still available today from art supply stores. People SHOULD NOT take Prussian blue artist’s dye in an attempt to treat themselves. This type of Prussian blue is not designed to treat radioactive contamination and is not made for that purpose. People who are concerned about the possibility of being contaminated with radioactive materials should go to their doctors for advice and treatment. Use of Prussian blue to treat radioactive contamination Since the 1960s, Prussian blue has been used to treat people who have been internally contaminated with radioactive cesium (mainly Cs-137) (http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/isotopes/cesium.asp) and nonradioactive thallium (once an ingredient in rat poisons). -

Color Stories 1

Extra Fine™ Watercolors Extra Fine Extra ™ Watercolor Stories Watercolor COLOR STORIES in brief Discover our world of pigments and how to incorporate each of their unique characteristics1 into your art. Alizarin Crimson Alizarin Crimson is the oldest synthetic deep red-crimson pigment. It is a lake pigment which when applied in strength and kept from the direct sunlight will last for many decades. Alizarin is a treat to paint with, just the sheer joy of the depth and uniqueness of color is invigorating. A beautiful bluish- red pigment from the staining family, Alizarin Crimson is listed on the basic palette of a vast majority of artists. Intense and dark in value, Alizarin Crimson mixes cleanly with most pigments to create dark mixtures and warm neutrals. A combination of Aureolin (Cobalt Yellow) and French Ultramarine with Alizarin renders a surprising range of other colors resembling everything from Burnt Sienna and Umber to Payne’s Gray, while Alizarin Crimson with French Ultramarine creates an intense purple. Alvaro’s Caliente Grey Alvaro’s Caliente Grey, “is a terrific hue, very powerful, excellent to create strong and warm paintings. In monochrome this wonderful Grey is perfect to achieve a powerful atmosphere with amazing glow. This color is also perfect to add dramatic highlights and shadows.” Alvaro’s Caliente and Fresco Greys, as he describes them, are about; “...magnetism, fury, energy...power. You know greys... create a feeling of danger, emotion, passion... mystery...evoke things that are unknown...darkness. I use these greys to create a painting that has a magnetism...energy, mystery, passion...something to discover, entering the unknown, darkness. -

Watercolor Color Chart

EVERY ARTIST DESERVES THE FINEST COLOR THAT CAN BE CREATED Bismuth Yellow Hansa Yellow Cadmium Yellow Light Azo Yellow Hansa Yellow Deep Cadmium Yellow Cadmium Yellow Deep 019, PY 184, LF I, O, G 107, PY 3, LF II, ST, S 070, PY 35, LF I, O, G 018, PY 151, LF I, T, S 106, PY 97, LF II, T, S 060, PY 35, LF I, O, G 063, PY 35, LF I, O, G Gamboge Indian Yellow Azo Orange Cadmium Orange Scarlet Pyrrol Quinacridone Red Cadmium Red Light 105, PY 151 & PO 62, LF I, T, S 109, PY 110, LF I, T, S 017, PO 62, LF II, T, S 038, PO 20, LF I, O, G 176, PO 73, LF I, T, S 155, PR 209, LF I, T, S 050, PR 108, LF I, O, G Naphthol Red Pyrrol Red Cadmium Red Cadmium Red Deep Quinacridone Rose Alizarin Crimson Permanent Alizarin 120, PR 112, LF II, T, S 154, PR 254, LF I, ST, S 040, PR 108, LF I, O, G 045, PR 108, LF I, O, G 156 , PV 19, LF I, T, S 010, PR 83, LF III, T, S Crimson 129, PR 264, LF II, T, S Maroon Perylene Quinacridone Violet Ultramarine Pink Mineral Violet Cobalt Violet Ultramarine Violet Dioxazine Purple 113, PR 179, LF I, T, S 158, PV 19, LF I, T, S 192, PR 258, LF I, SO, G 116, PV 16 & PV 15, LF I, SO, G 099, PV 14, LF I, ST, G Deep 100, PV 23, LF II, T, S 194, PV 15, LF I, T, G Ultramarine Violet Ultramarine Blue Cobalt Blue Anthraquinone Blue Cerulean Blue Cerulean Blue Deep Phthalocyanine Blue 193, PB 29 & PV 15, LF I, T, G 190, PB 29, LF I, T, G 090, PB 28, LF I, ST, G 012, PB 60, LF I, T, S 080, PB 36, LF I, SO, G 081, PB 36, LF I, SO, G Red Shade 141, PB 15:0, LF I, T, S Prussian Blue Phthalocyanine Blue Manganese Blue Hue Cobalt Teal