Shakespeare Seminar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

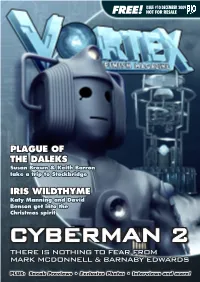

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

Christina Scherrer

Christina Scherrer Geboren in Pfarrkirchen im Mühlkreis in Oberösterreich. Schauspielstudium an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Graz (Mag. Art. 2009). Die vielseitige Schauspielerin ist auch als Sängerin in mehreren Formationen aktiv. Seit 2015 Zusammenarbeit mit Andrej Prozorov & Gründung des Ensembles SCHERRER&PROZOROV. Vertreten durch: Screen Actors Künstlermanagement OG, Geusaugasse 46/1, 1030 Wien, Österreich +43 664 2265650 / [email protected] www.screenactors.at FN49406s PREISE & STIPENDIEN 2016 Stipendium des BKA für die Masterclass „The method of Theodoros Terzopulos“ in Athen 2016 2ter Platz beim deutschen Chanson,- und Liedermacherpreis TROUBADOUR 2013 OÖ Nachwuchskünstlerinnenpreis YOUNGSTAR 2011 Start-Stipendium des BmuKK TALENTE INSTRUMENT Violine, Ukulele, Klavier (GK) DIALEKT Oberösterreichisch, Mühlviertlerisch SPRACHE Deutsch, Englisch (fliessend), Spanisch (GK) KAMPF Schwertkampf bei ROBERTA BROWN SPORT Bühnenakrobatik, Windsurfen, Tischfußball TANZ Tango Argentino, Modern, Standard, Jazz GESANG Klassisch und Jazz bei LILJANA VRBANCIC SPEZIALITÄT Interpretation Kabarettlied, Chanson THEATERPRODUKTIONEN // Auswahl // 2017 WA „Schatten“ / E.Jelinek / Gastspieltournee R: Sabine Mitterecker AUS HEITEREM HIMMEL / B. Strehlau / Kosmostheater Wien R: Bärbel Strehlau ZUSAMMEN IST MAN WENIGER ALLEIN / A. Bechstein / Schlosstheater Traun R: Daniel Pascal 2016 SCHATTEN / Elfriede Jelinek / Premiere: 13. Oktober im F23 Wien R: Sabine Mitterecker MASTERCLASS „The Method of Theodoros Terzopulos“ mit T. Terzopulos -

I Can't Recall As Exciting a Revival Sincezeffirelli Stunned Us with His

Royal Shakespeare Company The Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BB Tel: +44 1789 296655 Fax: +44 1789 294810 www.rsc.org.uk ★★★★★ Zeffirelli stunned us with his verismo in1960 uswithhisverismo stunned Zeffirelli since arevival asexciting recall I can’t The Guardian on Romeo andJuliet 2009/2010 134th report Chairman’s report 3 of the Board Artistic Director’s report 4 To be submitted to the Annual Executive Director’s report 7 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 10 September 2010. To the Governors of the Voices 8 – 27 Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is hereby given that the Annual Review of the decade 28 – 31 General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard Transforming our Theatres 32 – 35 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 10 September 2010 commencing at 4.00pm, to Finance Director’s report 36 – 41 consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial Activities and the Balance Sheet Summary accounts 42 – 43 of the Corporation at 31 March 2010, to elect the Board for the Supporting our work 44 – 45 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be transacted at the Annual General Meetings of Year in performance 46 – 49 the Royal Shakespeare Company. By order of the Board Acting companies 50 – 51 The Company 52 – 53 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors Corporate Governance 54 Associate Artists/Advisors 55 Constitution 57 Front cover: Sam Troughton and Mariah Gale in Romeo and Juliet Making prop chairs at our workshops in Stratford-upon-Avon Photo: Ellie Kurttz Great work • Extending reach • Strong business performance • Long term investment in our home • Inspiring our audiences • first Shakespearean rank Shakespearean first Hicks tobeanactorinthe Greg Proves Chairman’s Report A belief in the power of collaboration has always been at the heart of the Royal Shakespeare Company. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Players of Shakespeare

POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page i Players of Shakespeare This is the fourth volume of essays by actors with the Royal Shake- speare Company. Twelve actors describe the Shakespearian roles they played in productions between and . The contrib- utors are Christopher Luscombe, David Tennant, Michael Siberry, Richard McCabe, David Troughton, Susan Brown, Paul Jesson, Jane Lapotaire, Philip Voss, Julian Glover, John Nettles, and Derek Jacobi. The plays covered include The Merchant of Venice, Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Taming of the Shrew, The Winter’s Tale, Romeo and Juliet, and Macbeth, among others. The essays divide equally among comedies, histories and tragedies, with emphasis among the comed- ies on those notoriously difficult ‘clown’ roles. A brief biographical note is provided for each of the contributors and an introduction places the essays in the context of the Stratford and London stages. POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page ii POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page iii Players of Shakespeare Further essays in Shakespearian performance by players with the Royal Shakespeare Company Edited by Robert Smallwood POSA01 08/11/1998 10:09 AM Page iv The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge , United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge , United Kingdom West th Street, New York, –, USA Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne , Australia © Cambridge University Press, This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in ./pt Plantin Regular A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Players of Shakespeare : further essays in Shakespearian performance /by players with the Royal Shakespeare Company; edited by Robert Smallwood. -

Theater in England Syllabus 2010

English 252: Theatre in England 2010-2011 * [Optional events — seen by some] Monday December 27 *2:00 p.m. Sleeping Beauty. Dir. Fenton Gay. Sponsored by Robinsons. Cast: Brian Blessed (Star billing), Sophie Isaacs (Beauty), Jon Robyn (Prince), Tim Vine (Joker). Richmond Theatre *7:30 p.m. Mike Kenny. The Railway Children (2010). Dir. Damian Cruden. Music by Christopher Madin. Sound: Craig Veer. Lighting: Richard G. Jones. Design: Joanna Scotcher. Based on E. Nesbit’s popular novel of 1906, adapted by Mike Kenny. A York Theatre Royal Production, first performed in the York th National Railway Museum. [Staged to coincide with the 40 anniversary of the 1970 film of the same name, dir. Lionel Jefferies, starring Dinah Sheridan, Bernard Cribbins, and Jenny Agutter.] Cast: Caroline Harker (Mother), Marshall Lancaster (Mr Perks, railway porter), David Baron (Old Gentleman/ Policeman), Nicholas Bishop (Peter), Louisa Clein (Phyllis), Elizabeth Keates Mrs. Perks/Between Maid), Steven Kynman (Jim, the District Superintendent), Roger May (Father/Doctor/Rail man), Blair Plant(Mr. Szchepansky/Butler/ Policeman), Amanda Prior Mrs. Viney/Cook), Sarah Quintrell (Roberta), Grace Rowe (Walking Cover), Matt Rattle (Walking Cover). [The production transforms the platforms and disused railway track to tell the story of Bobby, Peter, and Phyllis, three children whose lives change dramatically when their father is mysteriously taken away. They move from London to a cottage in rural Yorkshire where they befriend the local railway porter and embark on a magical journey of discovery, friendship, and adventure. The show is given a touch of pizzazz with the use of a period stream train borrowed from the National Railway Museum and the Gentlemen’s saloon carriage from the famous film adaptation.] Waterloo Station Theatre (Eurostar Terminal) Tuesday December 28 *1:45 p.m. -

Freddie Stewart Actor

Freddie Stewart Actor Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company ALLIED RAF Officer Robert Zemeckis Paramount Pictures BLIND MAN'S DREAM Joe David Abramsky Mojo Pictures MACBETH Malcom Daniel Coll MGB Media Television Production Character Director Company THE ALIENIST Reporter Nick Oldham TNT KISS ME FIRST Kyle/Force Netlifx/Channel 4 HOLBY CITY River Kidd Various BBC NEW WORLDS Robert Charles Martin New Worlds / Channel 4 Stage Production Character Director Company HENRY V King Henry V John Risebero, Ben Antic Disposition Horslen United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company OTHELLO Cassio Bill Buckhurst Shakespeare's Globe PHAEDRA'S LOVE Various Roles Iqbahl Khan RADA SIX PICTURES OF LEE Cocteau/Dave Scherman Edward Kemp RADA MILLER EVERYMAN Ensemble/Musician Martin Oelbermann RADA KING LEAR Edmund Edward Kemp RADA THE GRACE OF MARY Giles/Hardlong Trilby James RADA TRAVERSE THE TEMPEST Trinculo Zoe Waites RADA MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S Bottom Nick Allen Shakespeare in Styria DREAM MACBETH Malcom Daniel Winder Shakespeare in Styria HAMLET Bernardo/Ostrick Daniel Winder Shakespeare in Styria Additional information Accents & Dialects: American-New York, American-Southern States, American-Standard, (* = native) Cockney, East European, Edinburgh, Glasgow, London*, RP*, South African Music & Dance: Choral Singing*, Guitar*, Modern Dance, Piano, Singer-Songwriter, Tenor* (* = highly skilled) Performance: Actor-Musician, Musical Theatre, Physical Theatre, Theatre In Education Sports: Football, Horse-riding, Martial Arts*, Rugby, Stage Combat* (* = highly skilled) Vehicle Licences: Car Driving Licence Other Skills: Devising, Drama Workshop Leader, Improvisation, Photography United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected]. -

LOCANTRO Theatre

Tony Locantro Programmes – Theatre MSS 792 T3743.L Theatre Date Performance Details Albery Theatre 1997 Pygmalion Bernard Shaw Dir: Ray Cooney Roy Marsden, Carli Norris, Michael Elphick 2004 Endgame Samuel Beckett Dir: Matthew Warchus Michael Gambon, Lee Evans, Liz Smith, Geoffrey Hutchins Suddenly Last Summer Tennessee Williams Dir: Michael Grandage Diana Rigg, Victoria Hamilton 2006 Blackbird Dir: Peter Stein Roger Allam, Jodhi May Theatre Date Performance Details Aldwych Theatre 1966 Belcher’s Luck by David Mercer Dir: David Jones Helen Fraser, Sebastian Shaw, John Hurt Royal Shakespeare Company 1964 (The) Birds by Aristophanes Dir: Karolos Koun Greek Art Theatre Company 1983 Charley’s Aunt by Brandon Thomas Dir: Peter James & Peter Wilson Griff Rhys Jones, Maxine Audley, Bernard Bresslaw 1961(?) Comedy of Errors by W. Shakespeare Christmas Season R.S.C. Diana Rigg 1966 Compagna dei Giovani World Theatre Season Rules of the Game & Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello Dir: Giorgio de Lullo (in Italian) 1964-67 Royal Shakespeare Company World Theatre Season Brochures 1964-69 Royal Shakespeare Company Repertoire Brochures 1964 Royal Shakespeare Theatre Club Repertoire Brochure Theatre Date Performance Details Ambassadors 1960 (The) Mousetrap Agatha Christie Dir: Peter Saunders Anthony Oliver, David Aylmer 1983 Theatre of Comedy Company Repertoire Brochure (including the Shaftesbury Theatre) Theatre Date Performance Details Alexandra – Undated (The) Platinum Cat Birmingham Roger Longrigg Dir: Beverley Cross Kenneth -

Die Komödie Der Irrungen

PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION DIE KOMÖDIE DER IRRUNGEN von WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Shakespeare im Park - Open Air Es spielen: Jürgen HEIGL (Antipholus v. Syrakus & Ephesus) Daniel JEROMA (Dromio v. Syrakus & Ephesus) Dragana WESHMASHINA (Adriana/Lucie) Claudia KOHLMANN (Luciana/Angelo) Christoph J. HIRSCHLER (Solinus/Dr. Zwack) Michael ZWIAUER (Egeon/Kurtisane) Regie & Bühne: Eric LOMAS Kostümbild: Maria KREBS Produktionsleitung: Paul ELSBACHER Eine Produktion von „Shakespeare im Park“ PREMIERE Steiermark: Fr. 22. Juli 2016 Foto von: Hannah Neuhuber, (Beginn: 18.30 Uhr) Abdruck bei Namensnennung honorarfrei Weitere Vorstellung: 23. Juli 2016 (18.30 Uhr) PRESSEFOTODOWNLOAD: BENEDIKTINER STIFT http://www.gamuekl.org (unter "Theater" anklicken) ST. LAMBRECHT A-8813 St. Lambrecht; Hauptstraße 1 Wir ersuchen um Die Vorstellung findet bei jeder Witterung statt. Berichterstattung und stehen in allen weiteren _________________________________________________________________ Fragen, für die Vereinbarung von Interview-Terminen und PREMIERE Wien: Mi. 27. Juli 2016 Reservierung von Pressekarten (Beginn: 19.00 Uhr) gerne unter Tel. 0699-1-913 14 11 Weitere Vorstellungen (19.00 Uhr): oder E-Mail: 28., 29., 30. Juli 2016 [email protected] 2., 3., 4., 5., 6. August 2016 zu Ihrer Verfügung. in den Gärten von Mit freundlichen Grüßen SCHLOSS PÖTZLEINSDORF Gabriele Müller-Klomfar A-1180 Wien; Geymüllergasse 1 Pressebetreuung Bei Schlechtwetter findet die Vorstellung im Festsaal des Schlosses statt Pressebetreuung: GAMUEKL – Gabriele Müller-Klomfar A-1047 Wien; Postfach 17 Mobil: 0699-1-913 14 11; E-Mail: [email protected]; www.gamuekl.org PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION+++PRESSEINFORMATION Die Komödie der Irrungen von William Shakespeare IM STIFT ST. LAMBRECHT: Bei Schlechtwetter findet die Vorstellung in der ehemaligen Tischlerei des Stiftes statt. IN WIEN: Bei Schlechtwetter findet die Vorstellung im Festsaal des Schlosses statt. -

The Uses of Richard

The Uses oi Richard Ilh From Robert Cecil to Richard Nixon M. G. AuNE North Dakota State University Ln Eikonoklastes (1649), his attack on the recently executed Charles I's Eikon Basilike, Milton demonstrates Charles' hypocrisy and ignorance by quoting from a work he is sure the King would have known: Shakespeare's Richard III. Milton writes William Shakespeare; [in 2.1] . introduces the Person of Richard the third speaking in as high a straine of pietie and mortification, as is utterd in any passage of this Book ...[:] 'I doe not know that Englishman alive With whom my soule is any jott at odds More then the Infant that is borne to night; I thank my God for my humilitie.' Other stuff of this sort may be read throughout the Whole Tragedie. (11) Not only does Milton assume, correctly, that Charles had read and probably seen Shakespeare's play, he assumes that his own reader is fa- miliar with the character of Richard as a notorious dissembler. Milton depends on this familiarity to advance his argument about the validity of the new government. In other words, his intent is to use the dramatic character of Richard (rather than the historical figure) to vilify Charles' and justify his execution. Milton's propagandistic use of Richard is one example of how in early modern England this particular character shifted from the sphere of dramatic entertainment to become available as a tool for personal attack and political commentary. This essay will examine the character of Richard III and the social and sometimes political uses to which it has been put in two distinct cultural moments: early modern England and postwar England and America. -

Shakespeare by Sophie Chiari

Shakespeare by Sophie Chiari Performances of William Shakespeare's plays on the European continent date back to his lifetime. Since his death in 1616, the playwright has never stopped dominating European literature. His Complete Works have gone through an incredible number of editions from the 18th century onwards. During the second half of the 18th century, he was translated into French and German. Yet in Southern Europe it was not until the 19th century that spectators became genuinely acquainted with his plays. In the 20th century, artists started to engage with the cultural traditions of Shakespeare in a variety of ways. By the 1980s, the playwright had not only become enrolled in the ranks of postcolonial critique, but he was also part and parcel of a European theatrical avant-garde. In today's Europe, newly created festivals as well as Shakespearean adaptations on screen continue to provide challenging interpretations of his plays. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Shakespeare's Immediate Afterlife 2. Shakespeare Lost in 18th-Century Translations 3. Romanticism and Bardolatry in 19th-Century Europe 4. 20th- and 21st-Century Shakespeare: From Politics to Multiculturalism 5. Appendix 1. Translations of Single Works by William Shakespeare 2. Sources and Complete Works Editions 3. Literature 4. Notes Indices Citation Shakespeare's Immediate Afterlife The English author William Shakespeare (1564–1616) (➔ Media Link #ab) wrote poetry (sonnets and narrative poems) as well as 38 plays – 39 if one includes Double Falsehood, that is, Lewis Theobald's (1688–1744) (➔ Media Link #ac) 1727 reconstruction of a lost play, which was based on Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra's (1547–1616) (➔ Media Link #ad) Don Quixote and originally entitled Cardenio. -

Ultimateregeneration1.Pdf

First published in England, January 2011 by Kasterborous Books e: [email protected] w: http://www.kasterborous.com ISBN: 978-1-4457-4780-4 (paperback) Ultimate Regeneration © 2011 Christian Cawley Additional copyright © as appropriate is apportioned to Brian A Terranova, Simon Mills, Thomas Willam Spychalski, Gareth Kavanagh and Nick Brown. The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. Internal design and layout by Kasterborous Books Cover art and external design by Anthony Dry Printed and bound by [PRINTER NAME HERE] No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photocopying or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form binding or cover other than that in which it is published for both the initial and any subsequent purchase. 2 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Christian Cawley is a freelance writer and author from the north east of England who has been the driving force behind www.kasterborous.com since its launch in 2005. Christian’s passion for Doctor Who and all things Time Lordly began when he was but an infant; memories of The Pirate Planet and Destiny of the Daleks still haunt him, but his clearest classic Doctor Who memory remains the moment the Fourth Doctor fell from a radio telescope… When the announcement was made in 2003 that Doctor Who would be returning to TV, Christian was nowhere to be seen – in fact he was enjoying himself at the Munich Oktoberfest.