A Very Peculiar Practice and Campus Comedy: 35 Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilt : (Wilt Series 1) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WILT : (WILT SERIES 1) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tom Sharpe | 336 pages | 15 Mar 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099435488 | English | London, United Kingdom Wilt : (Wilt Series 1) PDF Book Photo 4. Symptom of bacterial wilt of tomato caused by R. Gnanamanickam, ed. Those Who Are Loved. Disease cycle and epidemiology. The Thursday Murder Club. Daughtrey, Cornell University. Under favorable conditions, tomato plants infected with R. Jordan , I. Despite her appearance and quirky behavior, she can demonstrate a perceived intelligence, principle and kindness. Accurate identification of R. There are a great many parasitic forms, including pathogens in most plants, animals, and also in humans root-knot nematode can cause injury to plant roots and favor penetration of the bacterium. Once in this state, he becomes impossible to control, will often become obsessed with seeking any other source of sugar. View other formats and editions. Transplants are either field-grown not common anymore or container-grown in greenhouses. Biological control agents of plant diseases are most often referred to as antagonists Biological control , based on use of R. Game Log Summary. Pages in: Compendium of tomato diseases. However, because of the risk of its possible re-introduction and its potential to affect potato in the northern United States, R. Both race 1 and race 3 can cause bacterial wilt of tomato with similar disease symptoms. Additionally, resistance in these cultivars may vary with location and temperature, because of strain differences. Pradhanang, P. External Reviews. In natural habitats, R. As Wilt lies down on the ground in defeat, he is greeted by not originally his friends, but also his own creator, Jordan Michaels a parody of Michael Jordan. -

The Routledge History of Literature in English

The Routledge History of Literature in English ‘Wide-ranging, very accessible . highly attentive to cultural and social change and, above all, to the changing history of the language. An expansive, generous and varied textbook of British literary history . addressed equally to the British and the foreign reader.’ MALCOLM BRADBURY, novelist and critic ‘The writing is lucid and eminently accessible while still allowing for a substantial degree of sophistication. The book wears its learning lightly, conveying a wealth of information without visible effort.’ HANS BERTENS, University of Utrecht This new guide to the main developments in the history of British and Irish literature uniquely charts some of the principal features of literary language development and highlights key language topics. Clearly structured and highly readable, it spans over a thousand years of literary history from AD 600 to the present day. It emphasises the growth of literary writing, its traditions, conventions and changing characteristics, and also includes literature from the margins, both geographical and cultural. Key features of the book are: • An up-to-date guide to the major periods of literature in English in Britain and Ireland • Extensive coverage of post-1945 literature • Language notes spanning AD 600 to the present • Extensive quotations from poetry, prose and drama • A timeline of important historical, political and cultural events • A foreword by novelist and critic Malcolm Bradbury RONALD CARTER is Professor of Modern English Language in the Department of English Studies at the University of Nottingham. He is editor of the Routledge Interface series in language and literary studies. JOHN MCRAE is Special Professor of Language in Literature Studies at the University of Nottingham and has been Visiting Professor and Lecturer in more than twenty countries. -

Redgrove Papers: Letters

Redgrove Papers: letters Archive Date Sent To Sent By Item Description Ref. No. Noel Peter Answer to Kantaris' letter (page 365) offering back-up from scientific references for where his information came 1 . 01 27/07/1983 Kantaris Redgrove from - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 365. Peter Letter offering some book references in connection with dream, mesmerism, and the Unconscious - this letter is 1 . 01 07/09/1983 John Beer Redgrove pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 380. Letter thanking him for a review in the Times (entitled 'Rhetoric, Vision, and Toes' - Nye reviews Robert Lowell's Robert Peter 'Life Studies', Peter Redgrove's 'The Man Named East', and Gavin Ewart's 'The Young Pobbles Guide To His Toes', 1 . 01 11/05/1985 Nye Redgrove Times, 25th April 1985, p. 11); discusses weather-sensitivity, and mentions John Layard. This letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 373. Extract of a letter to Latham, discussing background work on 'The Black Goddess', making reference to masers, John Peter 1 . 01 16/05/1985 pheromones, and field measurements in a disco - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref No 1, on page 229 Latham Redgrove (see 73 . 01 record). John Peter Same as letter on page 229 but with six and a half extra lines showing - this letter is pasted into Notebook one, Ref 1 . 01 16/05/1985 Latham Redgrove No 1, on page 263 (this is actually the complete letter without Redgrove's signature - see 73 . -

English Literature, History, Children's Books And

LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 DECEMBER 13 LONDON HISTORY, CHILDREN’S CHILDREN’S HISTORY, ENGLISH LITERATURE, ENGLISH LITERATURE, BOOKS AND BOOKS ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS 13 DECEMBER 2016 L16408 ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS FRONT COVER LOT 67 (DETAIL) BACK COVER LOT 317 THIS PAGE LOT 30 (DETAIL) ENGLISH LITERATURE, HISTORY, CHILDREN’S BOOKS AND ILLUSTRATIONS AUCTION IN LONDON 13 DECEMBER 2016 SALE L16408 SESSION ONE: 10 AM SESSION TWO: 2.30 PM EXHIBITION Friday 9 December 9 am-4.30 pm Saturday 10 December 12 noon-5 pm Sunday 11 December 12 noon-5 pm Monday 12 December 9 am-7 pm 34-35 New Bond Street London, W1A 2AA +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com THIS PAGE LOT 101 (DETAIL) SPECIALISTS AND AUCTION ENQUIRIES For further information on lots in this auction please contact any of the specialists listed below. SALE NUMBER SALE ADMINISTRATOR L16408 “BABBITTY” Lukas Baumann [email protected] BIDS DEPARTMENT +44 (0)20 7293 5287 +44 (0)20 7293 5283 fax +44 (0)20 7293 5904 fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 [email protected] POST SALE SERVICES Kristy Robinson Telephone bid requests should Post Sale Manager Peter Selley Dr. Philip W. Errington be received 24 hours prior FOR PAYMENT, DELIVERY Specialist Specialist to the sale. This service is AND COLLECTION +44 (0)20 7293 5295 +44 (0)20 7293 5302 offered for lots with a low estimate +44 (0)20 7293 5220 [email protected] [email protected] of £2,000 and above. -

Illusion and Reality in the Fiction of Iris Murdoch: a Study of the Black Prince, the Sea, the Sea and the Good Apprentice

ILLUSION AND REALITY IN THE FICTION OF IRIS MURDOCH: A STUDY OF THE BLACK PRINCE, THE SEA, THE SEA AND THE GOOD APPRENTICE by REBECCA MODEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (Mode B) Department of English School of English, Drama and American and Canadian Studies University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers how Iris Murdoch radically reconceptualises the possibilities of realism through her interrogation of the relationship between life and art. Her awareness of the unreality of realist conventions leads her to seek new forms of expression, resulting in daring experimentation with form and language, exploration of the relationship between author and character, and foregrounding of the artificiality of the text. She exposes the limitations of language, thereby involving herself with issues associated with the postmodern aesthetic. The Black Prince is an artistic manifesto in which Murdoch repeatedly destroys the illusion of the reality of the text in her attempts to make language communicate truth. Whereas The Black Prince sees Murdoch contemplating Hamlet, The Sea, The Sea meditates on The Tempest, as Murdoch returns to Shakespeare in order to examine the relationship between life and art. -

Reading for Pleasure

1130 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 3 NOVEMBER 1979 Reading for Pleasure Chance acquaintances B N BROOKE British Medical_Journal, 1979, 2, 1130-1131 frequently expresses nostalgia and deplores the invasion of modernity brought about by social changes in the aftermath of war-just as we do today. It was out of politeness, really, that I came across it. "Going to "But the hateful, unmanly insolence of these lords of the soil, Sicily ?" they said, a rhetorical question natural to the course now they have their various 'unions' behind them and their of the conversation. "Then you must read Sea and Sardinia." rights as working men, sends my blood black. They are ordinary "I have a copy," said one. So I borrowed it; reluctantly, for men no more: the human, happy Italian is most marvellously D H Lawrence has never held my attention. All those lovers, vanished. New honours come upon them, etc. The dignity of Sons, Lady Chatterley's, even Women in Love have been opened, human labour is on its hind legs, busy giving every poor attempted, shut. But as I had borrowed the book-only too innocent who isn't ready for it a kick in the mouth." That obviously a cherished early Penguin edition (ads at the back of "etc" jars, a sudden discordant note, uncharacteristic in a flow- recent fiction included I Claudius, Brighton Rock, The Moon and ing euphonious text presenting an aquarelle that has not faded Sixpence)-so, in deference, I must read it. I was immediately with time. enchanted. Even in the squalor of a British Rail commuter train, transportation was complete, away from seedy suburban destinations into trains, boats, and buses in Sicily, Sardinia, Contrasting views of life and, above all, into the writer's presence, into the intimacy of his very mind, his thoughts shared only with me-not even with I can never be sure whether the pleasure I have obtained the queen bee, referred to as the qb after the first reference who, from a book is wholly intrinsic. -

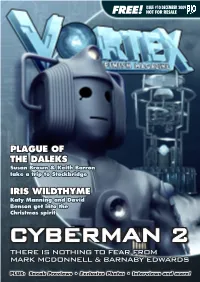

Plague of the Daleks Iris Wildthyme

ISSUE #10 DECEMBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE PLAGUE OF THE DALEKS Susan Brown & Keith Barron take a trip to Stockbridge IRIS WILDTHYME Katy Manning and David Benson get into the Christmas spirit CYBERMAN 2 THERE IS NOTHING TO FEAR FROM MARK MCDONNELL & barnaby EDWARDS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL THE BIG FINISH SALE Hello! This month’s editorial comes to you direct Now, this month, we have Sherlock Holmes: The from Chicago. I know it’s impossible to tell if that’s Death and Life, which has a really surreal quality true, but it is, honest! I’ve just got into my hotel to it. Conan Doyle actually comes to blows with Prices slashed from 1st December 2009 until 9th January 2010 room and before I’m dragged off to meet and his characters. Brilliant stuff by Holmes expert greet lovely fans at the Doctor Who convention and author David Stuart Davies. going on here (Chicago TARDIS, of course), I And as for Rob’s book... well, you may notice on thought I’d better write this. One of the main the back cover that we’ll be launching it to the public reasons we’re here is to promote our Sherlock at an open event on December 19th, at the Corner Holmes range and Rob Shearman’s book Love Store in London, near Covent Garden. The book will Songs for the Shy and Cynical. Have you bought be on sale and Rob will be signing and giving a either of those yet? Come on, there’s no excuse! couple of readings too. -

I Can't Recall As Exciting a Revival Sincezeffirelli Stunned Us with His

Royal Shakespeare Company The Courtyard Theatre Southern Lane Stratford-upon-Avon Warwickshire CV37 6BB Tel: +44 1789 296655 Fax: +44 1789 294810 www.rsc.org.uk ★★★★★ Zeffirelli stunned us with his verismo in1960 uswithhisverismo stunned Zeffirelli since arevival asexciting recall I can’t The Guardian on Romeo andJuliet 2009/2010 134th report Chairman’s report 3 of the Board Artistic Director’s report 4 To be submitted to the Annual Executive Director’s report 7 General Meeting of the Governors convened for Friday 10 September 2010. To the Governors of the Voices 8 – 27 Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford-upon-Avon, notice is hereby given that the Annual Review of the decade 28 – 31 General Meeting of the Governors will be held in The Courtyard Transforming our Theatres 32 – 35 Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on Friday 10 September 2010 commencing at 4.00pm, to Finance Director’s report 36 – 41 consider the report of the Board and the Statement of Financial Activities and the Balance Sheet Summary accounts 42 – 43 of the Corporation at 31 March 2010, to elect the Board for the Supporting our work 44 – 45 ensuing year, and to transact such business as may be transacted at the Annual General Meetings of Year in performance 46 – 49 the Royal Shakespeare Company. By order of the Board Acting companies 50 – 51 The Company 52 – 53 Vikki Heywood Secretary to the Governors Corporate Governance 54 Associate Artists/Advisors 55 Constitution 57 Front cover: Sam Troughton and Mariah Gale in Romeo and Juliet Making prop chairs at our workshops in Stratford-upon-Avon Photo: Ellie Kurttz Great work • Extending reach • Strong business performance • Long term investment in our home • Inspiring our audiences • first Shakespearean rank Shakespearean first Hicks tobeanactorinthe Greg Proves Chairman’s Report A belief in the power of collaboration has always been at the heart of the Royal Shakespeare Company. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'. -

Hamlet West End Announcement

FOLLOWING A CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED & SELL-OUT RUN AT THE ALMEIDA THEATRE HAMLET STARRING THE BAFTA & OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING ANDREW SCOTT AND DIRECTED BY THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR ROBERT ICKE WILL TRANSFER TO THE HAROLD PINTER THEATRE FOR A STRICTLY LIMITED SEASON FROM 9 JUNE – 2 SEPTEMBER 2017 ‘ANDREW SCOTT DELIVERS A CAREER-DEFINING PERFORMANCE… HE MAKES THE MOST FAMOUS SPEECHES FEEL FRESH AND UNPREDICTABLE’ EVENING STANDARD ‘IT IS LIVEWIRE, EDGE-OF-THE-SEAT STUFF’ TIME OUT Olivier Award-winning director, Robert Icke’s (Mary Stuart, The Red Barn, Uncle Vanya, Oresteia, Mr Burns and 1984), ground-breaking and electrifying production of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, starring BAFTA award-winner Andrew Scott (Moriarty in BBC’s Sherlock, Denial, Spectre, Design For Living and Cock) in the title role, will transfer to the Harold Pinter Theatre, following a critically acclaimed and sell out run at the Almeida Theatre. Hamlet will run for a limited season only from 9 June to 2 September 2017 with press night on Thursday 15 June. Hamlet is produced by Ambassador Theatre Group (Sunday In The Park With George, Buried Child, Oresteia), Sonia Friedman Productions and the Almeida Theatre (Chimerica, Ghosts, King Charles III, 1984, Oresteia), who are renowned for introducing groundbreaking, critically acclaimed transfers to the West End. Rupert Goold, Artistic Director, Almeida Theatre said "We’re delighted that with this transfer more people will be able to experience our production of Hamlet. Robert, Andrew, and the entire Hamlet company have created an unforgettable Shakespeare which we’re looking forward to sharing even more widely over the summer in partnership with Sonia Friedman Productions and ATG.” Robert Icke, Director (and Almeida Theatre Associate Director) said “It has been such a thrill to work with Andrew and the extraordinary company of Hamlet on this play so far, and I'm delighted we're going to continue our work on this play in the West End this summer. -

Porterhouse Blue, 1974, Tom Sharpe, 0136856934, 9780136856931, Prentice Hall, 1974

Porterhouse Blue, 1974, Tom Sharpe, 0136856934, 9780136856931, Prentice Hall, 1974 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1LmQ0Dy http://goo.gl/REhsI http://www.abebooks.com/servlet/SearchResults?sts=t&tn=Porterhouse+Blue&x=51&y=16 DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/ROJ2q http://bit.ly/1n1kxw1 Riotous Assembly , Tom Sharpe, 1987, Fiction, 248 pages. A South African woman struggles to convince the police that she has murdered her black cook.. The corrida at San FelГu , Paul Scott, Edward Thornhill, 1964, India, 316 pages. Louisa the Poisoner , Tanith Lee, 2005, Fiction, 80 pages. Raised in a swamp by a mad witch, poor Louisa grew up with one goal in mind: to marry a wealthy man, then inherit his lands and money by whatever means it takes. And Louisa may. A dialogue of proverbs , John Heywood, 1963, Proverbs, English, 300 pages. Twist of Fate , Linda Randall Wisdom, Mar 1, 1996, Fiction, 250 pages. Cross My Heart, Hope (Not) to Die Two Silver Lockets, One Promise to Heal, Melissa Ford, Apr 6, 2010, Fiction, 253 pages. Taylor and Jessica are best friends that have almost everything in common--including life-threatening illnesses. The one difference is, Jessica's is voluntary. Jessica Anderson. History of Warfare , Raintree Steck-Vaughn Publishers, Westwell, Brewer, Marshall, Samantha, Grant, Rickford, Sommerville, Tom Sharpe, Apr 1, 1999, Juvenile Nonfiction, 80 pages. Ten titles describe the causes, consequences, strategies, weaponry, and key figures of warfare from ancient times to the present. Authentic photographs of modern wars transport. The Messiah Containing All the Music of the Principal Songs, Duets, Choruses, Etc, George Frideric Handel, 1867, Oratorios, 26 pages. -

The Revival of the Satiric Spirit in Contemporary British Fiction1

The Revival of the Satiric Spirit in Contemporary British Fiction1 Luis Alberto Lázaro Lafuente University of Alcalá Satiric novels have traditionally been regarded as a minor form by many critics and scholars. Aristotle had already referred to the satirists as "the more trivial" poets who wrote about the actions of meaner~persons, in stark contrast to the "more serious-minded" epic poets who represented noble actions and the lives of noble people (1965: 35-36). This attitude has persisted throughout many centuries in the history of English literature. Even though satire enjoyed its golden age in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, especially with the poetry of such distinguished writers as Dryden or Pope, satiric compositions in prose did not really achieve the same high position2• When with time the novel became a well• established genre, it was mainly naturalistic fiction and psychological stories that commonly attained a prominent status among the literary critics, whereas the comic and satiric novel, with a few exceptions, was relegated to a status of popular prose on the fringe of the canon, or even outside it. Indeed, in the twentieth century, several prestigious authors have offered a rather gloomy picture of the state of novelistic satire. Robert C. Elliott, for instance, said in 1960 that the great literary figures of this century were not "preeminently satirists" (1970: 223); and Patricia Meyer Spacks, in her artide "Some Reflections on Satire" first published in 1968, even stated that satiric novel s by authors such I Some ideas oí this paper have already appeared in my essay "El espíritu satírico en la novela británica contemporánea: Menipo redivivo", included in the volume edited by Fernando Galván Már• genes y centros en la literatura británica actual.