Retiring Old Cars: Programs to Save Gasoline and Reduce Emissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Todd Rundgren: Not Just for Athletes, P

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 09/12/07 :: 02.37 :: FREE PEACE DAY, P. 6 THE NYLONS, P. 23 GOING GREEK, P. 39 FUNNY BUSINESS Northwest Clown Festival, P.20 BROKEN SPOKE FEST: FAREWELL TO GP: TODD RUNDGREN: NOT JUST FOR ATHLETES, P. 19 RUN OF THE MILL, P.8 STILL IN THE GAME, P. 22 WE’VE GOT SPIRIT, HOW ‘BOUT YOU?! ] 39 ][ FOOD Sept. 16th, 1-6pm 32-38 32-38 @ Depot Market Square WARNING: SERIOUS LAUGHTER MAY OCCUR ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ 26-31 26-31 FEATURING: the .2k Harvest Chase ][ FILM ][ RACING STARTS AT 2PM 22-25 22-25 Garden of Spirits Hosted by Boundary Bay Brewery, featuring local brews and wines from our region's finest A little out of the way… Joel Ricci's West Sound Union ][ MUSIC ][ 21 on the main stage from 1-2pm and 5-6pm Food Vendors But worth it. wood-fired Pizzazza pizza, Mallard Ice Cream, ][ ART ][ Diego's Mexican goodies, and more 20 20 Kindred Kids Corner Veggie Toss, Veggie 500 racing - games and fun for kids of all ages with the Be Local to benefit Sustainable Connections’ Food & Farming Program ][ ON STAGE ][ 19 Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 Visit our website for more info www.SustainableConnections.org ][ GET ][ OUT Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 18 18 ][ WORDS ][ & COMMUNITY 8-17 8-17 ][ CURRENTS ][ 6-7 6-7 ][ VIEWS ][ 4-5 4-5 Performing Arts Center Series2007-2008 ][ MAIL ][ Rachael Price - Friday, October 26, 2007 3 up-and-coming female jazz vocalist For tickets please call the DO IT IT DO Trio Mediæval - Thursday, November 29, 2007 WWU Box Office at 360.650.6146 polyphonic mediaeval music or go online at www.tickets.wwu.edu .07 www.pacseries.wwu.edu 12 Le Trio Joubran - Friday, February 15, 2008 09. -

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

Music Spectrum Page 1 of 13

Music Spectrum Page 1 of 13 BlogThis! music spectrum REVIEWING MUSIC ACCORDING TO A SPECTRUM OF STYLES AND DISCUSSING THE CONNECTION TO THE CHRISTIAN FAITH saturday, february 04, 2006 music sp The Shawano Snowy Retreat Issue (February) Music Spect Contact Inf Advertising This is called the Shawano Snowy Retreat Issue, because most of the writing happened during my Spectrum O off-time during my personal pastoral retreat up Alphabetica here in the central part of Wisconsin. I’ve been at a retreat center looking out on a frozen Shawano music sp (shaw-no) Lake with a nice blanket of snow closet = f coming down one day. After spending a good part of each day doing things like prepping for sermons, writing Bible studies, etc., it was good to also think about some tunes! I’m hiring! I need someone to spend about 3 hours doing some cut-and-paste computer work to help Giveaway Clo me update the Spectrum index page. In exchange Send an ema for your help, I can offer you $10 and 10 CDs from musicspectru the Giveaway Closet. Experience with Word and on how to ge Excel is necessary. A little knowledge of HTML code try to match your favorite is helpful, but if you’ve worked with anything like will be asked Blogger or other sites, it’ll be no problem. If you’d postage (or $ like the job, please email me, benjamin[at] International additional po musicspectrum.org. through PayP Thanks for reading! Email addres addresses wi purpose of se February Contents name and inf (All reviews appear on this page. -

2006 TRASH Regionals Round 15 Bonuses

2006 TRASH Regionals Round 15 Bonuses 1. Ever wonder how some ice cream flavors or treats came about? Given a description of the origins of a type of ice cream or ice cream treats, name it for 10 points each. (a) In addition to describing the ice cream’s texture, this flavor, allegedly invented in 1929 by William Dreyer, accurately depicts the paths of many Americans during the Great Depression. Answer: rocky road (b) This flavor, a version of spumoni, was popular in Europe in the early 19th century, and was likely introduced to the US in the 1870s where it took on the tripartite form we know now. Answer: Neapolitan (c) An entrepreneur in Boston; David Strickler in Latrobe, Pennsylvania; and Ernest Hazard of Wilmington, Ohio, all claim its invention around the turn of the century, but there is little doubt that it was popularized by Walgreen’s, who made it their signature dish. Answer: banana split 2. Hello, Cleveland! The Browns were one of the busiest shoppers this offseason. Name these newest members of the Dawg Pound, for ten points each. (a) Cleveland’s biggest pickup on defense was this longtime Patriots linebacker who is now reunited with current Browns head coach and former New England defensive coordinator Romeo Crennel. Answer: Willie McGinest (b) The Browns also beefed up the offensive line by signing this Saints All-Pro center and former star lineman at Ohio State. Answer: LeCharles Bentley (c) Cleveland got some additional receiving help by signing this former Penn State receiver who led the Seahawks with 10 touchdown catches last season. -

This PDF Is a Selection from an Out-Of-Print Volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Recent Economic Changes in the United States, Volumes 1 and 2 Volume Author/Editor: Committee on Recent Economic Changes of the President's Conference on Unemployment Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-012-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/comm29-1 Publication Date: 1929 Chapter Title: Marketing Chapter Author: Melvin T. Copeland Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c4959 Chapter pages in book: (p. 321 - 424) CHAPTER V MARKETING MELVIN T. COPELAND In the marketing field, the changes which have occurred since 1922 have been fully as notable as the changes in most other types of business activity, and of as great significance to the community.In order to keep the subject within manageable proportions for this survey, the .topics selected for concentrated study, on the ground that they are of particular significance or of especial interest, are as follows: changes in demand, changes in retail trading areas, hand-to-mouth buying, changes in dis- tribution, co-operative marketing, installment selling, and advertising. As the facts brought out in the analyses of these various topics will show, there have been numerous cross-currents and counter-currents among the marketing influences at work.While these conflicting influ- ences have benefited some industries and trades, they have reacted adversely upon other types of business.The purpose of this chapter is to show, so far as possible, the changes that have occurred and their relation to the general economic structure of the country. -

Making Cars More Fuel Efficient

EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY making cars more fuel efficient Technology for Real Improvements on the Road page2-20x27-IEA 14/03/05 9:54 Page 1 INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The International Energy Agency (IEA) is an autonomous body which was established in November 1974 within the framework of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to implement an international energy programme. It carries out a comprehensive programme of energy co-operation among twenty-six of the OECD’s thirty member countries. The basic aims of the IEA are: • to maintain and improve systems for coping with oil supply disruptions; • to promote rational energy policies in a global context through co-operative relations with non-member countries, industry and international organisations; • to operate a permanent information system on the international oil market; • to improve the world’s energy supply and demand structure by developing alternative energy sources and increasing the efficiency of energy use; • to assist in the integration of environmental and energy policies. The IEA member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States. The European Commission takes part in the work of the IEA. © OECD/IEA, 2005 No reproduction, copy, transmission or translation of this publication may be made without written permission. Applications should be sent to: International Energy Agency (IEA), Head of Publications Service, 9 rue de la Fédération, 75739 Paris Cedex 15, France. -

Backstage Auctions, Inc. the Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog

Backstage Auctions, Inc. The Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog Lot # Lot Title Opening $ Artist 1 Artist 2 Type of Collectible 1001 Aerosmith 1989 'Pump' Album Sleeve Proof Signed to Manager Tim Collins $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1002 Aerosmith MTV Video Music Awards Band Signed Framed Color Photo $175.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1003 Aerosmith Brad Whitford Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1004 Aerosmith Joey Kramer Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1005 Aerosmith 1993 'Living' MTV Video Music Award Moonman Award Presented to Tim Collins $4,500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1006 Aerosmith 1993 'Get A Grip' CRIA Diamond Award Issued to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1007 Aerosmith 1990 'Janie's Got A Gun' Framed Grammy Award Confirmation Presented to Collins Management $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1008 Aerosmith 1993 'Livin' On The Edge' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1009 Aerosmith 1994 'Crazy' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1010 Aerosmith -

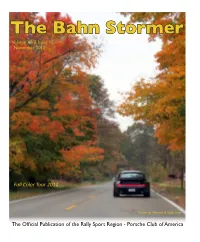

The Bahn Stormer Volume XVII, Issue 8 -- September 2012 Volume XVII, Issue 10 -- November 2012

The Bahn Stormer Volume XVII, Issue 8 -- September 2012 Volume XVII, Issue 10 -- November 2012 Fall Color Tour 2012 Photo by Stewart & Sally Free The Official Publication of the Rally Sport Region - Porsche Club of America The Bahn Stormer Contents For Information on, or submissions to, The Bahn Stormer contact Mike O’Rear at The Official Page .......................................................3 [email protected] or 734-214-9993 Traction Control.......................................... ..............4 (Please put Bahn Stormer in the subject line) Calendar of Events........................................... .........6 Deadline: Normally by the end of the third Membership Page ....................................................9 week-end of the month. Fall Color Tour .........................................................10 RSR Elections ..........................................................12 For Commercial Ads Contact Jim Christopher at Time With Tim ........................................................13 [email protected] Proper Storage of Your Porsche ..............................15 In The Zone .............................................................16 Advertising Rates (Per Year) Full Page: $650 Quarter Page: $225 An Englishman’s View .............................................17 Half Page: $375 Business Card: $100 Ramblings From a Life With Cars ............................19 Busted!! ..................................................................21 Udder Truth ............................................................23 -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT on most significant events of 2014 radio year and core trends in streaming broadcast and music industry' development of 2015 Part 1 – RADIO STARS & RADIO HITS ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ”, 127018 РОССИЯ, МОСКВА, СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, ДОМ 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 111, +7 (495) 645 78 55, +44 20 7193 7003, +1 (347) 274 88 41, +49 69 5780 1997, WWW.TOPHIT.RU CONTENTS Introduction.………………….…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Radio stars and radio hits…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Artists and songs – Top Hit Music Awards 2015 winners…….…………………………………………………….……… 6 Achievements of record labels in 2014…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Top 10 of Companies with biggest number of spins on radio air……………………..……………………………….. 8 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on radio air …………………………………………………………. 9 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of spins per each song………………………………………………………. 10 Top 10 Companies with biggest number of songs on TOP HIT 100 radio chart…………………………………. 11 Top 10 Companies with best song test results …………………………………………………………………………………. 12 Top 100 of most frequently rotated local and foreign songs on Moscow radio air 2014…………………… 13 Top 20 of hot rotation playlists, set music trends on Moscow radio air 2014.…………………………………… 15 2015: Top Hit 3.0 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 19 About the author……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 20 1 ООО “СОВРЕМЕННЫЕ МЕДИА ТЕХНОЛОГИИ” 125130 РОССИЯ МОСКВА СТАРОПЕТРОВСКИЙ ПРОЕЗД, 11, КОРП. 1, ОФИС 102 +7 495 645 7855 +44 20 7193 7003 +1 347 274 8841 +49 69 5780 1997 WWW.TOPHIT.RU Introduction Every day hundreds of millions of people listen to radio, driving their cars. Music, news, programs and advertising are delivered in single information flows to listeners. Today the radio air brodcast is gradually replaced by the Internet streaming, and the place of customary radiostations and TV sets is more often taken by desktops, tablet PCs and smartphones with various entertainment apps in them. -

Todd Rundgren Information

Todd Rundgren I have been a Todd Rundgren fan for over 40 years now. His music has helped me cope with many things in my life including having RSD and now having an amputation. I feel that Todd is one of the most talented musician, song writer and music producer that I have ever met in my life. If you have ever heard Todd's music or had an opportunity to see Todd in concert, you will know what I mean. Most people do not know who Todd Rundgren is. Most people say Todd who? Todd's best-known songs are "Can We Still Be Friends," "Hello, It's Me" "I Saw the Light," "Love is the Answer," and "Bang on the Drum All Day" (this is the song that you hear at every sporting event). Todd is also known for his work with his two bands Nazz and Utopia, while producing records for artists such as Meat Loaf, Hall and Oats, Grand Funk Railroad, Hiroshi Takano, Badfinger, XTC, and the New York Dolls. Eric and Todd Rundgren in Boston, MA February 4, 1998 Eric and Todd Rundgren in Salisbury, MA September 14, 2011 Eric and Michele Rundgren in Salisbury, MA September 14, 2011 Eric and Todd Rundgren in S. Dartmouth, MA October 20, 2012 Todd News Todd Rundgren Concert Tour Dates Please click on the following link below to view Todd's concert tour dates. http://www.todd-rundgren.com/tr-tour.html http://www.rundgrenradio.com/toddtours.html To view a recent concert that Todd did in Oslo, Norway please click on the following link: http://www1.nrk.no/nett-tv/klipp/503541 Todd Rundgren Concert Photo's Photo By: Eric M. -

Solar Matters II Teacher Page

Solar Matters II Teacher Page World Population Note: This activity is intended for advanced and/or upper elementary students. Student Objectives The student: Key Words: • can explain how population, energy fossil fuel consumption and limited natural J curve resources are connected population • will list renewable and non- renewable energy renewable energy sources. Materials: Time: • World Population video (see Internet 1 hour Sites section for link) Background Information* A graph of human population before the agricultural revolution would likely have suggested a wave, reflecting growth in times of plenty and decline in times of want, as graphs of other species’ populations continue to look to this day. The graph of recent human population growth is referred to as a J curve as it follows the shape of that letter, starting out low and skyrocketing straight up. World population is currently at 7.3 billion, and is expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2025. At the present rate of growth; nearly 80 million a year, the world adds a New York City every month, a Germany every year and a Europe each decade. The United States, with over 320 million people, is growing by more than 2.3 million people each year. At this rate, we are one of the fastest growing industrialized nations in the world, and we have the third largest population of all nations, preceded only by China and India. With a current annual growth rate of 1.1%, world population is projected to double in just 63 years. However, this doubling time will be realized if and only if growth rates remain constant. -

The Street Railway Journal

Vbl. VIII. NEW YORK $ CHICAGO, FEBRUARY. No. 2. Electric Cars in Albany. Rapid Transit in Omaha. THE OMAHA STREET RAILWAY. Under the heading “Notes from the Field,” in the January issue of the Street Railway Journal, we gave a The present company who control all lines running detailed account of the operation of the electric lines of in Omaha with the exception of that to Council Bluffs, the Albany Railway Co. In the same connection we take and the Benson & Halcyon Heights Railway, a suburban pleasure in presenting the accompanying illustrations, line, are composed of three originally distinct companies, Fig. i illustrates, in a striking manner, the old and the the Omaha Cable Tramway, the Omaha Horse Railway new in the evolution of rapid transit. The car shown to and the Omaha Motor Co. The result of the simultane- the left of the figure is one of the original horse cars with ous existence of these three roads, until their consolida- FIG. I.—THE OLD AND THE NEW IN RAPID TRANSIT—ALBANY, N. Y., STREET RAILWAY. which the lines were equipped. The centre figure is of a tion, was great competition which damaged all three, by horse car that was employed on State Street before the building unnecessary lines, and by running some in the advent of electric traction, and which ordinarily required wrong direction. The three companies, appreciating their four horses to haul up the steep grade, and frequently in imprudence, very sensibly joined hands and formed the snowy weather six horses. An electric car with which the Omaha Street Railway Co.