Download.Php

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs CoMTrans UrbanTransport Master Plan Final Report CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1.1 Definition The Western Province is the most developed province in Sri Lanka and is where the administrative functions and economic activities are concentrated. At the same time, forestry and agricultural lands still remain, mainly in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the province. And also, there are some local urban centres which are less dependent on Colombo. These areas have less relation with the centre of Colombo. The Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined in order to analyse and assess future transport demands and formulate a master plan. For this purpose, Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined by: A) areas that are already urbanised and those to be urbanised by 2035, and B) areas that are dependent on Colombo. In an urbanised area, urban activities, which are mainly commercial and business activities, are active and it is assumed that demand for transport is high. People living in areas dependent on Colombo area assumed to travel to Colombo by some transport measures. 4.1.2 Factors to Consider for Future Urban Structures In order to identify the CMA, the following factors are considered. These factors will also define the urban structure, which is described in Section 4.3. An effective transport network will be proposed based on the urban structure as well as the traffic demand. At the same time, the new transport network proposed will affect the urban structure and lead to urban development. -

Pre-Feasibility Study Inland Water Based Transport Project (Phase I) Western Province Sri Lanka

GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation in collaboration with Western Region Megapolis Planning Project Draft Report Pre-Feasibility Study Inland Water Based Transport Project (Phase I) Western Province Sri Lanka April 2017 1 PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY TEAM Name Designation Institute Dr. N.S. Wijayarathna Team Leader, Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Deputy General Development Corporation Manager (Wetland Management) Dr. Dimantha De Silva Deputy Team Leader, Western Region Megapolis Planning Transport Specialist, Project Senior Lecturer Transportation Engineering Division, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa Mr. R.M. Amarasekara Project Director, Ministry of Megapolis and Western Transport Development Development Project Dr. W.K. Wimalsiri Infrastructure Department of Mechanical Specialist Engineering Head of the University of Moratuwa Department Dr. H.K.G. Punchihewa Safely Specialist, Department of Mechanical Senior Lecturer Engineering University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka Mr. Nayana Mawilmada Head of Investments Western Region Megapolis Planning Project Mr. Thushara Procurement Western Region Megapolis Planning Sumanasekara Specialist Project Ms. Disna Amarasinghe Legal Consultant Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation Mrs. Ramani Ellepola Environmental Western Region Megapolis Planning Specialist Project Mr. Indrajith Financial Analyst Western Region Megapolis Planning Wickramasinghe Project -

Lions Club of Hanwelipura

Lions Club of Hanwelipura Club No: 058152 Chartered on22.04.1996 Region : 05 Zone : 01 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Extended By Lions Club of Avissawella Extension Chairman – Lion Tikiri Bandara Guiding Lion – Lion Tikiri Bandara & Ananda Zoysa District Governor then in Office – PDG Lion Late Roysten De Silva Club Executives PRESIDENT Lion S.Iddamalgoda M.No.1440800 Kahahean, Waga. Licensed Surveyor Tel: 036-2255282(R) L/L: Amitha SECRETARY Lion Deepani Gamage M.No. 2074390 “Sirisewana”, Welikanna, Waga. Human Resource Specialist – Swiss Embassy, Colombo Tel: 071-7057162(M),036-2255878(R) Email: [email protected] Spouse: Lion Prabhath TREASURER Lion Haritha Adhikari M.No. 1430107 No. 242/2, Araliya Sewana, Welikanna, Waga. Planter Tel: 071-3392484(M),036-2255340(R) L/L: Saumya District Cabinet Executives From Lions Club Of Diyawanna Oya CABINET SECRETARY Lion R.A.P.Ranasinghe M.No. 1440811 “Prabhavi”, Pahathgama, Hanwella. Attorney- at- Law : No. 4, Court Rd, Seethawaka, Avissawella. Tel: 071-8478826/077-6099461(M),036-2255205/4921808(R) Email: [email protected] L/L: Shirani DISTRICT GOVERNOR’S CHIEF PROGRAM COORDINATOR It & Communication Lion Prabhath S. Gamage M.No. 1435455 “Sirisewana”, Welikanna, Waga. General Manager – Mobitel Engineering Office, Colombo 05 Tel: 071-7310412(M),036-2255878(R) Email: [email protected] L/L: Lion Deepani DISTRICT GOVERNOR’S CHIEF PROGRAM COORDINATOR Women Membership Development,Co Chairperson District Get together Lion Deepani Gamage M.No. 2074390 “Sirisewana”, Welikanna, Waga. Human Resource Specialist – Swiss Embassy, Colombo Tel: 071-7057162(M),036-2255878(R) Email: [email protected] Spouse: Lion Prabhath Spouse: Lion PrabhathL/L: Priyanka DISTRICT GOVERNOR’S PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON - Club Supplies, International Shipments & Customs Lion S.D.Gamini M.No. -

Development of a Flood Forecasting Model for Kalu River and Kelani River Basins in Sri Lanka Using Radial Basis Function Neural Networks

Development of a Flood Forecasting Model For Kalu River and Kelani River Basins in Sri Lanka using Radial Basis Function Neural Networks Seenipellage Chaminda Sugeeswara Supervisor: Prof. A. W. Jayawardena MEE09208 Abstract This research is intended to investigate a kind of river stage/discharge forecasting model suitable for Sri Lankan flood prone rivers as an essential component of an effective early flood warning system. This work was carried out on a belief, that data driven river stage/discharge model would be more suitable for Sri Lankan rivers as there are considerable amount of past records of data while other physical information that are required to develop physically based models are rare. Artificial neural networks (ANN) have recently become popular in many fields including river stage/discharge forecasting in hydrology. Among various types of ANNs, radial basis function networks (RBFN) are popular over the more widely used multilayer perceptrone for its faster convergence, smaller extrapolation errors and higher reliability. In this study, generalized radial basis function network (GRBFN) with fully supervised algorithm (trained using daily data) was applied to two most flood prone river basins for forecasting one day ahead discharge at two respective river gauging stations. Upper Kalu River basin with smaller catchment area and smaller catchment response time did not show good forecasting results, but Kelani River catchment with comparatively large catchment area, with a response time of almost a day, showed good forecasting results. It was concluded that the GRBFN could be successfully applied to daily river stage/discharge forecasting for comparatively lager catchments with larger response time (close to a day). -

SRI LANKA Floods and Storms

SRI LANKA: Floods and 29 April 1999 storms Information Bulletin N° 01 The Disaster Unusually heavy rains for this time of year and violent thunderstorms along the western and south-western coast of Sri Lanka between 16 and 21 April caused widespread damage and severe floods in the south-west and south of the country. The main rivers, Kelani and Kalu, rose by over seven feet, and caused additional flooding, made worse by slow run-off. Some of the worst areas received as much as 290 mm of rain in 24 hours, and even the capital, Colombo, where 284 mm fell within 24 hours, experienced bad flooding in many sectors of the city. The worst affected districts are Ratnapura, Colombo, Kalutara, Gampaha, Galle, Kandy, Matara and Kegalle, all located between the coast and the Kandyan highlands. Six persons were reported killed by lightning, landslides or floods. Thousands of houses were damaged or destroyed, and initial official figures place the number of homeless at around 75,000 families (the average family in Sri Lanka consists of five members). In Colombo alone an estimated 12,400 families were affected. The damage is reportedly much worse in the rural areas particularly in Ratnapura District, but precise information is difficult to come by since many of the affected areas are totally cut off, with roads inundated and power and telephone lines damaged. The railway line from Colombo to Kandy has been blocked since 19 April, when boulders from a landslide damaged the tracks. FirstDistricts estimates of affected people areSub-Divisions as follows: -

Cover & Back of SLWC Volume 2

Identifying the Impact of Tidal Level Variation on River Basin Flooding M. D. E. K. Gunathilaka, W. A. L. Wikramanayake and D. N. D. Perera Department of Surveying and Geodesy, Faculty of Geomatics, Sabaragamuwa University of Sri Lanka, Belihuloya, Sri Lanka Abstract Different parts of Sri Lanka are regularly subjected to a wide range of natural disasters, of which floods are most common. When severe, flooding can decrease the economic and social development of the country and the Government of Sri Lanka has to spend huge amounts of money each year to address such problems. Floods occur mostly because of heavy rainfall combined with human-induced factors in the catchment areas. In this project, tidal level variation is considered as a factor for floods in the river basins. The tidal level changes periodically due to the gravitational attraction from the sun and the moon and the centrifugal force of the earth’s rotation. This project studied the relationship between changes in tide and river water level in the mouth of the Kelani River. Tidal data was collected from the Colombo Harbor, and water level data and river flow data was obtained from the Nagalagam Street gauge and Hanwella gauge. It was found that there is a direct relationship between tidal level and flood level in the river mouth area. Therefore, it is proposed that tidal level variations be considered in order to make accurate flood predictions in the river mouth areas. Introduction Flood is defined as a body of water that rises and overflows into land settlements that are not normally under water (Kulathilaka 2007). -

Towns East of Colombo District Water Supply Project)

Draft Initial Environmental Examination July 2013 SRI: Greater Colombo Water and Wastewater Management Improvement Investment Program (Towns East of Colombo District Water Supply Project) Prepared by the National Water Supply and Drainage Board Government of Sri Lanka for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 July 2013) Currency Unit – Sri Lanka rupees (SLRs) SLRs1.00 = $0.007645 $1.00 = SLRs. 130.80 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected person CEA – Central Environment Authority CCD – Coast Conservation Department CMC – Colombo Municipal Council DMA – district metering area EMP – environmental management plan GCWWMIIP – Greater Colombo Water and Wastewater Improvement Investment Program GN – Grama Niladhari GRC – grievance redressal committee GRM – grievance redress mechanism IEE – initial environmental examination MASC – management advisory and supervision consultant MWSD – Ministry of Water Supply and Drainage MLGPC – Ministry of Local Government and Provincial Council NRW – non-revenue water NWSDB – National Water Supply and Drainage Board O&M – operations and maintenance PMU – project management unit PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance PRO – public relations officer REA – rapid environmental assessment RSC – regional support center SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement WC – Western Central WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer m2 – square meter mm – millimeter m3/day – cubic meter per day NOTE{S} In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. “SLRs” and “ ” refer to Sri -

Ds Division : Hanwella

District: Colombo Administrative Map DS Division: Hanwella GNs P-Codes Area Detail Agra Pedesa 1115060 Akaravita 1115085 Aluth Ambalama 1115125 Aradhana Kanda 1115145 Kudagama Kanampella West Avissawella 1115050 Weralupitiya Bollathawa 1115005 Brandigampala 1115220 Eswatta North Diddeniya North 1115265 Manakada Diddeniya South 1115295 Kanampella East Digana 1115235 Agra Pedesa Seethagama Egodagama 1115160 Bollathawa Elamalawala 1115300 Eswatta North 1115025 Ukwatta Eswatta South 1115065 Kiriwandala North Gira Imbula 1115190 Avissawella Hanwella Town 1115205 Thawalgoda Hingurala 1115170 GAMPAHA Akaravita Seethawaka Ihala Hanwella North 1115210 Avissawella Muruthagama Ihala Kosgama North ! Ihala Hanwella South 1115270 Kahatapitiya Ihala Kosgama North 1115070 Eswatta South Ihala Kosgama South 1115115 Ilukovita 1115305 Kiriwandala South Kotahera Jayaweeragoda 1115280 Miriswatta Pahala Kosagama West Kadugoada North 1115175 Aradhana Kanda Legend Kosgama Kadugoda South 1115225 ! Kahahena 1115255 ! Kahatapitiya 1115090 Town Puwakpitiya Kalu Aggala 1115095 Salawa Pahala Kosgama East Ihala Kosgama South Aluth Ambalama Puwakpitiya ! Puwakpitiya South Kanampella East 1115015 Kalu Aggala Kanampella West 1115010 Kahatapitiya Railway Line Kiriwandala North 1115030 Kaluaggala Kiriwandala South 1115130 ! Weragolla North Track Road Koodaluvila 1115285 Kadugoada North Egodagama Koswatta 1115310 Kotahera 1115135 Minor Road Kudagama 1115035 Gira Imbula Hingurala Kudakanda 1115325 Lahirugama 1115240 Main Road Mambula 1115245 Suduwella Manakada 1115020 Uruwala -

Galle Kandy Matara Gampaha Colombo Kegalla

N u m b e r o f F a m i l i e s A f f e c t e d b y F l o o d s , 0 3 r d J u n e 2 0 0 8 - 1 2 . 0 0 h r s S r i L a n k a Nattandiya # of Affected # of Houses Damaged # of Affected Change on DS Divisions Persons Families Partially Fully District # Families Wennappuwa Rambukkana Gampaha 9 70,865 15,776 12,252 1 1 Dankotuwa Matara 7 8,900 1,755 1,505 5 3 Kalutara 11Kand1y02,250 26,601 6,943 58 51 Divulapitiya Rathnapura 8 29,197 6,892 204 404 22 Kegalla Mawanella Mirigama Galigamuwa Colombo 3 40,805 8,992 828 10 3 Warakapola # of Affected # of Affected # of Houses Damaged Kegalle Galle 6 No Data 5,218 2,576 0 0 Negombo District DS Divisions Families People Partially Fully Katana Kegalle 2 1,500 450 300 0 0 AranayakPauttalam 1 No Data 9 0 0 Gampaha 4 3524 17439 0 0 Minuwangoda Attanagalla Total 47 253,517 65,693 24,617 478 80 Mtatara 2 250 1350 0 0 Gampaha Bulathkohupitiya Ja-Ela Gampaha Kalutara 9 19658 65123 25 22 Ruwanwella Mahara Ratnapura 8 6688 24988 83 2 Yatiyanthota Wattala Colombo 4 8164 36349 0 0 Dompe Nuwara Eliya Kelaniya Biyagama Colombo Galle 3 2642 No Data 0 0 Dehiovita Kolonnawa Colombo Hanwella Kegalle 2 150 500 0 0 Deraniyagala Thimbirigasyaya Kaduwela Kotte Dehiwala Maharagama Homagama Padukka Eheliyagoda Rathmalana Kesbewa Kuruwita Moratuwa Ingiriya Horana Kiriella Rathnapura Panadura Bandaragama Imbulpe Ratnapura Millaniya Elapatha Madurawala Bulathsinhala Ayagama Pelmadulla Kaluthara Opanayaka Kalutara Balangoda Dodangoda Nivithigala Agalawatta Weligepola Kahawaththa Mathugama Palindanuwara Godakawela Beruwala Kalawana -

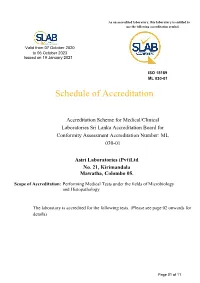

Scope of Accreditation: Performing Medical Tests Under the Fields of Microbiology and Histopathology

As an accredited laboratory, this laboratory is entitled to use the following accreditation symbol. Valid from 07 October 2020 to 06 October 2023 Issued on 19 January 2021 ISO 15189 ML 030-01 Schedule of Accreditation Accreditation Scheme for Medical/Clinical Laboratories Sri Lanka Accreditation Board for Conformity Assessment Accreditation Number: ML 030-01 Asiri Laboratories (Pvt)Ltd No. 21, Kirimandala Mawatha, Colombo 05. Scope of Accreditation: Performing Medical Tests under the fields of Microbiology and Histopathology. The laboratory is accredited for the following tests. (Please see page 02 onwards for details) Page 01 of 11 Sl Field of Test Test Method Test no Testing Instrument Urine Culture Manual Culture Method Identification and CLSI method -M100, ABST 29th Edition BAC 01 Microbiology Blood Automated Fluorometry BACTEC FX 200 Culture detection & processing Identification and Automated identification BD Phoenix M50 ABST & ABST using CLSI breakpoints 0 Biopsy Transport, Grossing, Tissue processor, 02 Histopathology Processing, embedding, Wax dispenser, cutting (2.5-4 µm), H Microtome, floating and E staining, water bath, Auto mounting, and Stainer, Microscope microscopic examination & cooling plate, Hot (under x 400) air oven ASH/HIS/SOP-02 Rev: 01 PAP smear Slide preparation PAP staining and microscopy ASH/HIS/SOP-01 Rev: 01 Page 02 of 11 Approved sample collection centres Si no Name of the sample Address Matrix of the sample collection canter 1. The Central Hospital No 114, Norris Canal Road, Serum, Plasma, Urine, Stool, Colombo 10. Blood, Tissue 2. Asiri Surgical No 21, Kirimandala Mawatha, Serum, Plasma, Urine, Stool, Hospital PLC Colombo 05. Blood, Tissue 3. Asiri Hospital Matara No 191, Anagarika Dharmapala Serum, Plasma, Urine, Stool, Pvt Ltd Mawatha, Matara . -

VACCINATION CENTERS OPEN on 01.08.2021 to 06.08.2021 Astrazeneca (2Nd Dose) Only

VACCINATION CENTERS OPEN ON 01.08.2021 to 06.08.2021 AstraZeneca (2nd Dose) Only District / Police Area Vaccination Centre Name Institution 1 Cinnamon Gardens Viharamahadevi Park Army Manned Walk-in 2 Narahenpita Army Hospital Narahenpita Vaccination Centres - Colombo Colombo 3 Boralesgamuwa Kotelawala Defence Hospital (SLAMC) Time - From 0700 Hrs to 1800 Hrs 4 Panagoda Bodirajaramaya 5 Talangama Diyatha Uyana (2nd August to 4th August Only) Sub Total 5 CMC - Air Force Vaccination 1 Cinnamon Gardens BMICH Centres - Colombo Colombo 2 Maligawatta PD Sirisena Ground Time - From 0900 Hrs to 1700 Hrs (SMS Appointment Only) 3 Grandpass Sugathadasa Stadium Sub Total 3 1 Moratuwa District Hospital Moratuwa 2 Athurugiriya District Hospital Athurugiriya 3 Nawagamuwa District Hospital Nawagamuwa 4 Piliyandala District Hospital Piliyandala Hospitals 5 Kahathuduwa District Hospital Wethara Colombo Time - From 0830 Hrs to 1700 Hrs 6 Awissawella DGH - Awissawella 7 Homagama Homagama Base Hospital 8 Kosgama District Hospital Kosgama 9 Thalangama Base Hospital Thalangama 10 Padukka District Hospital Padukka Data Collaboration - Research and Analysis Wing / State Intelligence Service and Epidemiology Unit / Ministry of Health 11 IDH - Angoda Mulleriyawa 12 CEBH - Mulleriyawa 13 Kohuwala CSTH - Kalubowila Sub Total 13 1 Thalangama MOH Office - Battaramulla 2 Boralesgamuwa MOH Office - Boralesgamuwa 3 Dehiwala MOH Office - Dehiwala 4 MOH Office - Moratuwa Moratuwa 5 MOH Office - Egodauyana 6 Gothatuwa MOH Office - Gothatuwa 7 Hanwella MOH Office - Hanwella -

MOH Area Code

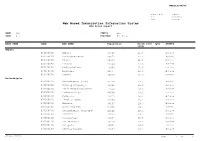

WEBIIS/AM/04 Generated By madzper Date 03/03/2016 Time 09:07 AM Web Based Immunization Information System MOH Areas Report NAME All STATUS ALL CODE All PROVINCE All Areas RDHS NAME CODE MOH NAME Population Birth rate (per STATUS 1000) Ampara 050160010 Ampara 45513 22.6 Active 050160020 Dehiattakandiya 62073 22.6 Active 050160030 Uhana 60666 22.6 Active 050160040 Mahaoya 21564 22.6 Active 050160050 Padiyathalawa 18956 22.6 Active 050160060 Lahugala 9265 22.6 Active 050160070 Damana 40067 22.6 Active Anuradhapura 070200010 Anuradhapura (cnp) 86299 19.3 Active 070200020 Kahatagasdigiliya 41825 19.3 Active 070200030 Kekirawa(palugaswewa) 77044 19.3 Active 070200040 Medawachchiya 48569 19.3 Active 070200050 Padaviya 23822 19.3 Active 070200060 Thambuttegama 43650 19.3 Active 070200070 Galnewa 36107 19.3 Active 070200080 Nochchiyagama 51678 19.3 Active 070200090 Anuradhapura (nnp/npe) 94202 19.3 Active 070200100 Mihintale 36516 19.3 Active 070200110 Rajanganaya 34637 19.3 Active 070200120 Horowpathana 38234 19.3 Active 070200130 Palagala 35031 19.3 Active 070200140 Kebethigollewa 23087 19.3 Active MOH Areas Report Page 1 of 13 WEBIIS/AM/04 RDHS NAME CODE MOH NAME Population Birth rate (per STATUS 1000) Anuradhapura 070200150 Galenbindunuwewa 48368 19.3 Active 070200160 Ipalogama 40142 19.3 Active 070200170 Thalawa 59930 19.3 Active 070200180 Thirappane 32063 19.3 Active 070200190 Rambewa 38233 19.3 Active Badulla 080220010 Badulla 77357 18.7 Active 080220020 Bandarawela 67396 18.7 Active 080220030 Girandurukotte 37586 18.7 Active 080220040