Interaction Through Manipulation by Ian Bellomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPAD A5 Public

APPLITHÈQUE IPad Découvrez notre sélection d’applications numériques pour enfants, disponibles sur les tablettes tactiles iPad de la médiathèque. Le mercredi matin et le samedi , en échange d'une pièce d'identité , les enfants de moins de 8 ans accompagnés d'un adulte peuvent emprunter pour une utilisation sur place l'un des 3 IPads mis à disposition par la médiathèque. Ces tablettes sont pré-chargées de dizaines d'applications sélectionnées, testées et approuvées par les bibliothécaires ! Pendant une demi-heure , les enfants peuvent ainsi lire ou inventer des histoires originales interactives, créer des personnages loufoques, apprendre autrement ou jouer, tout simplement… La consultation d’une tablette est limitée à 30 mn /enfant. La réservation d’un créneau horaire est seulement possible le jour-même (pas de réservation d’un jour sur l’autre). Liste des applications présentes sur les tablettes "IPad" : E-books (des livres à découvrir dans l'application iBooks) Et si la nuit... / Adèle Pedrola & Un album magnifique à mi-chemin entre Douglace (L'Apprimerie) réel et imaginaire. Calme et doux. (A partir de 4 ans) Le lapin bricoleur / Michaël Une histoire à faire évoluer soi-même, Leblond, Stéphane Kiehl, Ambroise dans le style graphique et minimaliste Cabry (E-Toiles éditions) propre aux éditions E-Toiles. Encore (A partir de 4 ans) une belle réalisation. L'Ours et la Lune / Cécile Alix, Pour découvrir le travail du sculpteur Antoine Guilloppé François Pompon dans un album (L'Élan vert & Canopé) interactif magnifiquement illustré par (A partir de 5 ans) Antoine Guilloppé. Mon voisin / Marie Dorléans (Ed. Un album à feuilleter en étages qui joue des Braques & Tralalère) avec les sons et l'imaginaire. -

Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design

The London School of Economics and Political Science Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design Siobhán Thomas A thesis submitted to the Department of Management of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 66,515 words. 2 Abstract The aim of this qualitative research study was to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of game designers from the particular vantage point of intersomatic awareness. Intersomatic awareness is an interbodily awareness based on the premise that the body of another is always understood through the body of the self. While the term intersomatics is related to intersubjectivity, intercoordination, and intercorporeality it has a specific focus on somatic relationships between lived bodies. This research examined game designers’ body-oriented design practices, finding that within design work the body is a ground of experiential knowledge which is largely untapped. To access this knowledge a hermeneutic methodology was employed. The thesis presents a functional model of intersomatic awareness comprised of four dimensions: sensory ordering, sensory intensification, somatic imprinting, and somatic marking. -

Appartaward 2014 Appartaward 2014

ZKM AppArtAward 2014 AppArtAward 2014 Vorwort/Preface 002 Künstlerischer Innovationspreis/ 005 Prize for Artistic Innovation Sonderpreis/Special Prize for 009 Crowd Art Sonderpreis/Special Prize for 013 Sound Art Sonderpreis/Special Prize for 017 Art and Science Weitere Highlights aus dem Wett - 021 bewerb/More Highlights from the Competition AppArtAward auf Reisen/on Tour 039 Liste der eingereichten Apps/ 043 List of Submitted Apps AppArtAward 2014 002 003 Vorwort Preface Das Phänomen »App« ist eine rasante globale Erfolgsgeschichte, ebenso wie der App- The phenomenon of apps has swiftly attained global success, as has the AppArtAward ArtAward, der im Jahr 2014 zum vierten Mal ausgeschrieben wurde. Seit 2011 wurden zum competition, which is being held for the fourth time in 2014. Since the first AppArtAward AppArtAward insgesamt 388 Apps aus 33 Ländern aus allen Teilen der Erde eingereicht. Prä- in 2011, a total of 388 apps from 33 countries around the world have been submitted, 13 of miert wurden davon dreizehn Apps in der Hauptkategorie Künstlerischer Innovationspreis them garnering € 125,000 in awards, both in the main prize category, the Artistic Innova- sowie in acht weiteren, wechselnden Kategorien. Insgesamt konnten 125.000 € an Preisgel- tion Award, and in eight additional rotating categories. For the most recent competition, dern ausgeschüttet werden. Für den aktuellen Wettbewerb kamen die Kategorien Sound the new prize categories of Sound Art and Art and Science have been added. Art und Art and Science hinzu. Since 2013, an AppArtAward exhibition has been traveling around the world: The win- Seit 2013 tourt eine Ausstellung des AppArtAward um die Welt. -

About Metamorphabet Website: Publisher: Vectorpark, Inc Release Date: April 29Th, 2015 Price: U.S.: $4.99

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 14th, 2015 Contact: Maya Bradford, Publicist [email protected] metamorphabet.com Metamorphabet Created by Patrick Smith Published by Vectorpark, Inc A playful, interactive alphabet for all ages “Metamorphabet is sweetness itself, but it is also gorgeously disturbing.” – Eurogamer “Every transformation is both unexpected and perfectly fluid. Like a dream, it’s totally nonsensical, but it makes perfect sense.” – Wired “The experience comes to life in robust, surprising animations full of elasticity, inventiveness and charm...” – Kotaku Released for iPad and iPhone earlier this year to rave reviews from users and critics alike, the IGF award-winning alphabet game Metamorphabet is coming on April 29th to Mac and PC desktop computers. Inspired by the popularity of his game Windosill among adults and kids alike, interactive artist Patrick Smith was drawn to reinvent the classic ABC book for his newest all-ages work. Starting with the familiar glyphs of the alphabet, he transformed each of the 26 letters into a series of playful, interactive vignettes. The resulting game, Metamorphabet is a beautifully designed experience brimming with luminous imagery and delightful surprises. With its child-friendly interface and responsive, organic design, Metamorphabet is a wonderful educational tool for children, inviting them to playfully explore the alphabet and expand their vocabulary. But it is also an incredible achievement of interactivity sure to engage adults, who will be enthralled by the game’s visually stunning and thoughtfully crafted universe. Metamorphabet is an intuitive game that draws children and adults alike into the meticulously imagined world of each letter of the alphabet. -

Aaa17 Broschuere 20170710-1 Low

Open Codes. zkm.de Leben in digitalen Welten 20.10. 2017 –– M a i 2 0 1 8 Die Welt verstehen, die wir bewohnen. Die Welt verstehen, in der wir leben. Die Welt verstehen, von der wir leben. 001 AppArtAward 2017 Vorwort/Preface 002 Preis für/ Prize for AppARTivism 006 Preis für/ Prize for Game Art 010 Preis für/ Prize for Sound Art 014 Weitere Highlights aus dem 020 Wettbewerb 2017/More Highlights from the Competition 2017 Best-of 2011–2017 032 AppArtAward auf Reisen /on Tour 042 Liste der 2017 eingereichten Apps/ 046 List of Submitted Apps 2017 AppArtAward 2017 002 Vorwort In der künstlerischen Gestaltung von Apps scheinen in rascher Folge neue Tendenzen auf. Diese ästhetischen und technischen Entwick- lungen zu begleiten und die besten Apps im Wettbewerb zu prämie- ren, ist das Anliegen des nun bereits zum siebten Mal ausgerichteten AppArtAwards. In der diesjährigen Ausschreibung wurde neben den zentralen Preiskategorien „Game Art“ und „Sound Art“ daher erstmals auch ein Preis in der Kategorie „AppARTivism“ ausgelobt. Die Verbin- dung aus Activism und Art, aus Aktivismus und Kunst, möchte den zahl- reichen Bereichen Rechnung tragen, in denen neue Medien künstlerisch für soziale oder politische Anliegen eingesetzt werden. So nutzt David Colombini mit seiner Web-Applikation Polluted Selfie narzisstische Sel- fies als Agenten gegen die Umweltverschmutzung und bietet damit einen kritischen Ansatz, um vor Augen zu führen, dass jedes Individuum zur Kli- makatastrophe beiträgt. Die synästhetische Komponente, die bereits für die Kunst des gesamten 20. Jahrhunderts kennzeichnend war, erzeugt auch bei Apps immer wieder künstlerisch wie technisch überraschende Ergebnisse. In diesem Jahr hat die Jury in der Kategorie „Sound Art“ zwei Apps ausgezeichnet (Mazetools Soniface von Jakob Gruhl und Stephan Kloß, Visual Beat von Max Mörtl), die beide auf unterschiedliche Weise die Aktualität des Genres unter Beweis stellen. -

Therapeutic Video Game Recommendations How to Use This Guide

Therapeutic Video Game Recommendations How to Use This Guide The purpose of this guide is to recommend therapeutic video games for children based on their symptoms. The games recommended in this guide were curated by researchers at EEDAR, a market-leading video game research firm, in collaboration with mental health researchers at UCSD. This guide was designed as a quick reference to help caretakers quickly select games for their patients. Caretakers can reference the category that best fits the symptoms of the patient and select one of the games listed. When selecting an appropriate game, the user should first select the appropriate symptom and age category of the child, and then select a title based on the available gaming platforms at the facility. Note: Virtual Reality Games are currently not recommended by the manufacturer for children under the age of 12. Methodology EEDAR operates the largest video game attribute database in the world containing over 170 million game facts. To create the recommendations in this guide, EEDAR collaborated with mental health researchers to create a hierarchy of over one hundred game features related to positive health. EEDAR then classified thousands of video games based on these features. EEDAR then collaborated with mental health researchers to determine which features should correspond to which symptom groups. EEDAR’s proprietary recommendation technology was used to select the titles recommended in this guide. Honorable Mention Good games specifically designed for a therapeutic purpose. › I, Hope (General Action) A beautiful coming of age adventure story about a young girl named Hope, whose town has been taken over by Cancer. -

Des Applis À La Bibli

Des applis à la bibli... Venez découvrir les tablettes en secteur jeunesse 11 Des " applis en folie " Le singe au chapeau / Chris Haughton pour les moins de 6 ans ! Le petit singe a besoin d’aide ! Il aime lire des histoires, parler au téléphone, jouer à cache cache ou danser et souhaite toujours que quelqu’un s’amuse avec lui. Une application très ludique et colorée à l’image des Histoires albums de C.Haughton. Renversant Pierre et le loup Cette application qui conviendra parfaitement aux Cette application vous propose un film, une série enfants à partir de 2 ans est à la fois un livre au texte d’expériences, des jeux d’écoute et des découvertes court sur le thème de « grandir » et un jeu qui permet inspirés du conte musical. Un véritable jeu d’éveil à la de faire participer l’enfant tout au long de sa lecture. musique. En un mot : génial ! Original ! Dans mon rêve Lil’Red Voici une approche originale de la poésie. Chaque Une petite merveille que ce Lil’Red : un petit chaperon enfant peut construire son histoire par un jeu de rouge très original. combinaison et se la faire raconter ensuite par la voix Ici pas de texte ni de narrateur, l’histoire se découvre du de Tom Novembre. bout des doigts en tapotant sur l’IPad. Sur chacun des 12 tableaux, l’enfant devra interagir avec le décor pour que l’histoire progresse. Le petit monde de Christian Voltz L’application reprend l’univers des albums de C.Voltz. Le Carnaval des animaux A chacun de choisir virtuellement un objet : une vis, un bout de tissu et de construire son personnage à la Une superbe promenade dans l’oeuvre de Camille manière de Voltz. -

2016-Catalogue-D Applications-Pour-Ipad.Pdf

Applis musicales Sago Mini Sound Box Pour les plus petits, sons 3 ans « Sago Mini Sound Box » : sons rigolos et sonorités amusantes pour les tout-petits. Cette boîte à musique, pleine de surprises sonores, s'adresse tout particulièrement aux plus jeunes ! Grâce à cette application magique, faites découvrir les sons et la musique aux enfants. Bougez tous azimuts pour écouter des carillons, des klaxons, des tambours, des animaux et bien plus encore. Ajoutez des notes en touchant l'écran, puis lancez-les dans tous les sens ou faites-les tomber. Chaque fois qu'elles rebondissent, elles produisent des sons rigolos. Regardez les enfants s'amuser avec les sonorités, explorer les couleurs et découvrir des surprises cachées. TuneTrace Appli de création musicale (Anglais mais très peu d’écrit dans l’appli) A partir de 3 ans Demandez d’abord aux enfants de vous faire un dessin avec des quadrillages, des lignes qui se croisent, des courbes et des diagonales. Une fois les dessins de vos enfants terminés, vous allez ouvrir l’application avec eux et prendre en photo leurs œuvres via l’appli. Attendez quelques secondes puis… voici le dessin de votre enfant transformé en partition de musique qui se met à jouer devant vos yeux. C’est assez magique à voir, cela fonctionne avec des dessins mais aussi des objets. Peinture musicale Jeu musical, dessins A partir de 3 ans Peinture musicale est une application pour les enfants à partir de 3 ans, pour dessiner librement et en musique. Avec en bonus une petite ville sous-marine à explorer. Gaspard : les aventures extraordinaires Jeu musical, instruments de musique, océan 3/5 ans "Gaspard : les Aventures Extraordinaires", c'est un véritable dessin animé interactif : l'histoire d'un petit garçon et de son copain Octave le poulpe qui partent à la recherche d'instruments de musiques disparus, sur terre, sur mer et au plus profond de l'océan.. -

Applications Numériques Pour Les Enfants

Applications numériques pour les enfants Sélection 2018 Sélection d’applications numériques pour les enfants Parmi l’offre foisonnante pour la jeunesse, voici quelques applications que nous avons sélectionnées pour leurs qualités. Pour vous guider : un descriptif le système : iPad ou Android l’âge conseillé le prix indicatif l’univers d’un auteur / illustrateur une œuvre de littérature jeunesse Ces applications sont consultables sur nos tablettes en section jeunesse à la Bibliothèque municipale, et vous sont présentées lors d’ateliers de découverte parents-enfants. Cache-cache ville Le livre blanc 3 ans et + 3 ans et + Sur iPad et Android, gratuit Sur Ipad, 1,09 € Vincent Godeau Tiwi Grâce à une loupe qui révèle des animations, Choisis ton pot de peinture puis colorie l’écran. l’enfant pourra parcourir la ville, ses immeubles et Soudain un animal apparaît et prend vie ! Derrière ses jardins. Il s’amusera à observer les véhicules chaque couleur se cache un animal différent. et les habitants, à dénicher les animaux dans les Un graphisme coloré pour une application de arbres. Une promenade imaginée par Vincent coloriage toute simple, qui initie les petits aux Godeau, à partager avec son enfant pour se laisser couleurs et leur fait reconnaître les animaux. surprendre. Prix Andersen 2014 de la meilleure création digitale Mention spéciale Bologne 2018 Miximal Fiete Hide & seek 3 ans et + 3 ans et + Sur Ipad, 2,99 € Sur iPad et Android, 3,99 € Yatatoy Ahoiii Entertainment Fiete joue à cache-cache avec les animaux, à À la manière d’un cadavre exquis, l’enfant crée l’enfant de les retrouver avec lui ! D’un abord de drôles de créatures en combinant la tête, le très simple et adaptée aux plus jeunes, cette corps et les pattes de différents animaux. -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

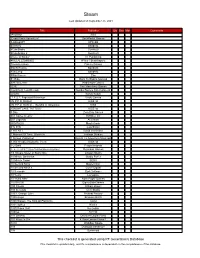

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Top Apps of 2015

Helping Teachers, Parents and Librarians Find Interactive Media Since 1993 Top 10 Tech Trends for ECE Educators, p. 5 Top100 Apps & Video Games of 2015 A look back at the work that is setting the standard. p. 6 LittleClickers: NAEYC update: What might Montessori, Piaget, High Tech Vygotsky & Skinner say about an iPad? p. 4 Holidays p. 3 Children’s Technology Review DecemberOn the cover: Goldilocks 2015 and Little Bear by Nosy Crow, reviews on page 20 iPad Pro*, p. 21 Samsung Gear VR (for select Kalley's Machine Plus Cats*, p. 21 Samsung devices), p. 27 Volume 23, No. 12, Issue 189 Kid Lid Protect Board, p. 22 Scribble - Creative Book Maker*, p. Kids Preschool Puzzles, p. 22 28 A Pickle In The Sky?, p 17 LBX: Little Battlers eXperience, p. 22 Sesame Street Alphabet Kitchen, p. Animal Crossing: amiibo Festival, p. Leonardo's Cat*, p. 23 28 17 Little Fox Animal Doctor, p. 23 Thomas & Friends: Express Delivery Animal Crossing: Happy Home Magic Moves RainbowJam, p. 24 Train, p. 28 Designer, p. 17 Mario's Alphabet*, p. 24 Zooper ABC Carmen Sandiego Returns, p. 18 Mega Man Legacy Collection, p. 24 Animals, p. 29 Chibi-Robo! Zip Lash, p. 18 Minecraft: Story Mode*, p. 25 Disney Infinity 3.0: Star Wars Rise National Geographic Puzzle Explorer, * Denotes Against The Empire Play Set, p. 18 “Editor’s Dr. Panda's Firemen*, p. 19 NYT VR*, p. 26 DragonBox Numbers*, p. 19 Ocean Forests*, p. 26 Choice.” Goldilocks and Little Bear*, p. 20 Runbow, p. 26 Sago Mini Superhero*, p.