Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update of Part Of

FIJI Introduction Area: 18,272 sq.km. Population: 827,900 (2007). Fiji is an independent island republic in the South Pacific, situated between latitudes 15° South and 21° South and straddling the 180th meridian from 177° West to 175° East. The 320 or so islands form a complex group of high islands of volcanic origin, with barrier reefs, atolls, sand cays and raised coral islands. The two largest islands, Viti Levu (10,386 sq.km) and Vanua Levu (5,535 sq.km), together comprise 87% of the total land area. Two smaller islands, Taveuni (435 sq.km) and Kadavu (408 sq.km), account for a further 4.6% of the land area, and most of the remaining islands are very small. Less than a hundred of the islands are inhabited, most of the population being concentrated in the towns, villages and lowlands of the two larger land masses. The annual population growth is 2% and the population density is 39 inhabitants per sq.km. Suva, the capital city, is located on a peninsula near the southeastern corner of Viti Levu. Fiji has an equable maritime climate, a consequence of its high topography and prevailing winds, the Southeast Trades. The west coast of Viti Levu is in a rain shadow, and thus experiences a distinct dry season. Maximum and minimum temperatures for Suva are 30°C and 20.5°C respectively. The dry season extends from May to October, and the wet season from November to April. Mean relative humidities are 80% and 75% at 0800 hrs and 1400 hrs respectively on the east coast, and about 10% lower on the west coast. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise Aboard MV Reef Endeavour

The Senior Newspaper and Travelrite International invite you to join them on the 2022 FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise aboard MV Reef Endeavour Denarau, Lau Islands and Kadavu Islands, Fiji 22 October to 5 November 2022 SENFIJI21 – GLG0740 FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise If you want to experience the real Fiji, join TOUR HIGHLIGHTS us on MV Reef Endeavour as we explore • Three nights at a Luxury Resort on Denarau the Lau Islands and Kadavu; a beautiful and Island, Fiji remote region rarely seen by tourists. A • Discover islands and reefs rarely visited by visit to this region offers a once in a lifetime tourists aboard MV Reef Explorer experience to a select few travellers, visiting • Visit the amazing Bay of Islands – a magnificent turquoise bays and remote villages where location with many limestone islands they only see a supply boat once a month. • Be treated to a song and dance by children of all ages from a local village • Snorkelling, glass bottom boat & dive opportunities daily Cruise highlights include a swim at a waterfall, exploring • Swim in some of the most pristine and clear old ruins, snorkelling untouched reefs and getting waters that the Lau group has to offer up close with nesting turtles. You’ll also explore the • Island Night, kava, meke & lovo feast caves, reefs and lagoons of Qilaqila renowned for its mushroom-shaped islands, and the central lake on uninhabited Vuaqava island where you’ll find turtles, TOUR ITINERARY snakes and amazing bird life. Best of all, you’ll be DAY 1: Saturday 22 October 2022 Depart/Denarau, Fiji welcomed and entertained by the friendly people of this Our holiday begins with our flight to Nadi, Fiji. -

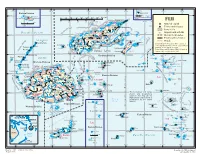

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES for FIJI – Exploration & Exploitation of Deep Sea Minerals

ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT ISSUES for FIJI – Exploration & Exploitation of Deep Sea Minerals 29 Nov – 2 Dec 2011 Denarau, Nadi, Fiji Mala Finau – Director Mineral Development INTRODUCTION • Fiji Island is located in the South-West Pacific Ocean • Comprised of over 322 islands • Total land area covers about 18,000 km² spread over 1.3 million km² of South Pacific Ocean • Volcanic origin but no active volcanoes • High central mountain ranges with several large rivers leading down to coastal plains, then beaches and mangrove swamps surrounded by shallow water and coral reefs • Tropical Climate – 2 distinct seasons • Nov – Apr : Wet & Cyclone Season • May – Oct : Dry, Cold What We Have • Waters of the Fiji Islands contain 3.12% of the world’s coral reefs including the Great Sea Reef, the third largest in the world. • Marine life includes over 390 known species of coral and 12,000 varieties of fish of which 7 are endemic. • Fiji waters are spawning ground for many species including the endangered hump head wrasse and bump head parrot fish. • Five of the world’s seven species of sea turtle inhabit Fiji water. • Marine Mineral Resources • Multi–Stakeholder agencies including communities involvement What We Have • Dedicated Govt. Depts. (Environment, Mineral Resources etc) • Dedicated environment units • Policy – Offshore Mineral Policy • Legislation – EMA (2005), Mining Act (1978), MEEB (2006) • ~ 50 Mineral Exploration Licenses (On-shore) • 3 Mines (On-shore) • 17 Deep Sea Mineral Exploration Licenses • “Interest” in the ISA (‘THE AREA’) Types of -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses. -

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji: landscapes, hotspots and ecological processes D avid O lson,Linda F arley,Alex P atrick,Dick W atling,Marika T uiwawa V ilikesa M asibalavu,Lemeki L enoa,Alivereti B ogiva,Ingrid Q auqau J ames A therton,Akanisi C aginitoba,Moala T okota’a,Sunil P rasad W aisea N aisilisili,Alipate R aikabula,Kinikoto M ailautoka C raig M orley and T homas A llnutt Abstract Fiji’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action goal of protecting 40% of remaining natural forests to Plan encourages refinements to conservation priorities based achieve the goals of the National Biodiversity Strategy and on analyses of new information. Here we propose a network Action Plan and sustain ecosystem services for Fijian com- of Priority Forests for Conservation based on a synthesis of munities and economies. new studies and data that have become available since Keywords Conservation priorities, ecosystem services, Fiji, legislation of the Action Plan in 2001. For selection of Pri- forest conservation, national biodiversity strategy, Oceania, ority Forests we considered minimum-area requirements protected area network, representation for some native species, representation goals for Fiji’s habitats and species assemblages, key ecological processes This paper contains supplementary material that can be and the practical realities of conservation areas in Fiji. found online at http://journals.cambridge.org Forty Priority Forests that cover 23% of Fiji’s total land area and 58% of Fiji’s remaining native forest were iden- tified. -

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania FIJI

A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania FIJI http://www.wetlands.org/inventory&/OceaniaDir/Fiji.htm INTRODUCTION by Alistair J. Gray Area: 18,272 sq.km. Population: 715,000 (1989). Fiji is an independent island republic in the South Pacific, situated between latitudes 15° South and 21° South and straddling the 180th meridian from 177° West to 175° East. The 320 or so islands form a complex group of high islands of volcanic origin, with barrier reefs, atolls, sand cays and raised coral islands. The two largest islands, Viti Levu (10,386 sq.km) and Vanua Levu (5,535 sq.km), together comprise 87% of the total land area. Two smaller islands, Taveuni (435 sq.km) and Kadavu (408 sq.km), account for a further 4.6% of the land area, and most of the remaining islands are very small. Less than a hundred of the islands are inhabited, most of the population being concentrated in the towns, villages and lowlands of the two larger land masses. The annual population growth is 2% and the population density is 39 inhabitants per sq.km. Suva, the capital city, is located on a peninsula near the southeastern corner of Viti Levu. Fiji has an equable maritime climate, a consequence of its high topography and prevailing winds, the Southeast Trades. The west coast of Viti Levu is in a rain shadow, and thus experiences a distinct dry season. Maxima and minima temperatures for Suva are 30°C and 20.5°C respectively. The dry season extends from May to October, and the wet season from November to April. -

Guide to Gender Statistics and Their Presentation

Sustainable Pacific development through science, knowledge and innovation Guide to gender statistics and their presentation Pacific Community | [email protected] | www.spc.int Headquarters: Noumea, New Caledonia Guide to gender statistics and their presentation Compiled by the Gender, Culture and Youth Section, Social Development Division, Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia, 2015 © Pacific Community (SPC) 2015. All rights for commercial/for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial/for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Pacific Community cataloguing-in-publication data Guide to gender statistics and their presentation / compiled by the Gender, Culture and Youth Section, Social Development Division, Pacific Community 1. Gender — Oceania. 2. Gender mainstreaming — Oceania. 3. Gender Identity — Oceania — Statistics. 4. Oceania — Sex differences — Statistics. 5. Women — Oceania — Statistics. 6. Men — Oceania — Statistics. I. Title II. Pacific Community 305. 30995 AACR2 ISBN: 978-982-00-0951-6 Prepared for publication at SPC’s Noumea headquarters BP D5, 98848 Noumea Cedex, New Caledonia 2015 Tel: +687 26 2000 Fax: +687 26 3818 Web: http://www.spc.int Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments The Guide to gender statistics and their presentation has been produced by the Progressing Gender Equality in Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PGEP) programme - an initiative within the Gender, Culture and Youth Section of the Social Development Division of SPC. -

Vanua Levu Vita Levu Suva

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 0 10 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Coral reefs Sasa Nasea l Cobia e n n Airports and airfields Pacific Ocean Navidamu Rabi a Labasa e y Nailou h v a C 16° 30’ Natua ro B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld ka o Nabiti Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu Bua conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua a parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. s Yandua Nadivakarua Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Nanuku Passage Viwa Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata tu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Wayalevu Malake - Vanua Balavu I- Nasau N r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna C H Kuata Tavua Vaileka h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Ra n Mago N Sorokoba n Lomaiviti -

Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji

R BAPID IOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY OF SOUTHERN LAU, FIJI BI ODIVERSITY C ONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 22 © 2013 Cnes/Spot Image BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern 22 Lau, Fiji Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 22: Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Marika Tuiwawa & Prof. William Aalbersberg, Institute of Applied Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: Fiji and the Lau Island group. Source: Google Earth. Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, Conservation International empowers societies to responsibly and sustainably care for nature for the well-being of humanity. ISBN 978-982-9130-22-8 © 2013 Conservation International All rights reserved. -

Vanua Levu Viti Levu

MA019 Index of Maps Page Page 2 Number Page Name Number Page Name 1 1 Rotuma 48 South Vanua Balavu Fiji: 2 Cikobia 49 Mana and Malolo Lailai S ° 3 6 3 Vatauna 50 Nadi 1 Cyclone Winston- 4 Kia 51 West Central Viti Levu 8 Index to 1:100 000 5 Mouta 52 Central Viti Levu 4 5 6 7 6 Dogotuki 53 Laselevu 16 Topographical Maps 7 Nagasauva 54 Korovou Labasa 8 Naqelelevu 55 Levuka Northern 10 11 12 13 14 15 9 Yagaga 56 Wakaya and Batiki 9 Index to 1:100 000 Topographical 10 Macuata 57 Nairai Vanua Levu 23 24 25 Series (MA003) with numbers and 11 Sasa 58 Cicia 17 19 20 21 22 26 names 12 Labasa 59 Tuvuca and Katafaga Yasawa 18 Savusavu 13 Saqan 60 West Viti Levu 31 14 Rabi 61 Narewa 27 28 29 30 15 Yanuca 62 South Central Viti Levu 37 38 Northern 16 Nukubasaga 63 East Cental Viti Levu 33 34 35 Lau Rotuma 17 Yasawa North 64 Nausori 32 36 18 Yadua 65 Gau Vaileka 46 47 48 19 Bua 66 Nayau Tavua 42 43 45 Central 39 40 41 Ba 44 20 Vanua Levu 67 Eastern Atolls Western Lautoka Vatukoula Lamaiviti 21 Wailevu 68 South West Viti Levu 59 49 50 53 54 55 56 58 22 Savusavu 69 Sigatoka Viti Levu 52 57 23 Tonulou 70 Queens Road 51 Korovou Nadi 67 24 Wainikeli 71 Navau S 66 ° 8 60 61 62 Central FIJI 25 Laucala 72 Suva 1 63 64 65 26 Wallagi Lala 73 Lakeba Sigatoka 27 Yasawa South 74 Vatulele 72 68 69 70 71 73 28 Vuya 75 Yanuca and Bega Vanua Levu 77 29 South 76 Vanua Vatu 75 76 30 Waisa 77 Alwa and Oneata 74 Taveuni 79 31 South 78 Dravuni 80 81 78 Viwa and Eastern 32 Waya 79 Moala 85 86 Naiviti and 82 83 84 33 Narara 80 Tavu Na Siel 34 Naba 81 Moce, Komu and Ororua