Guide to Gender Statistics and Their Presentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Fjf Lau & Kadavu Discovery Cruise Fact Sheet Reissued Nov15

11 Night Lau & Kadavu Discovery Cruise Embark on your voyage of discovery to a part of Fiji never seen by tourists. For the first time ever, Reef Endeavour will em- bark on a Discovery voyage of the Lau Group and Kadavu. Tuesday: Set sail on your Lau Discovery cruise. After boarding there will be a full briefing from your guide before an afternoon of beach activities at Tivua Island. Later in the evening, enjoy a wonderful Welcome dinner as you cruise into a south pacific sunset. Wednesday: Start your day at Makogai Island with a traditional Fijian ceremony before joining the 1hour walking tour of Mako- gai leper colony and nursery, home to giant clams and turtles. In the afternoon return to the island visiting the local primary school where the children will entertain you with their song and dance. Thursday: Explore a beautiful beach on the rugged southern coastline of Taveuni at Lavena, take a hike to a spectacular water- fall and fresh water pool and enjoy a picnic lunch ashore and a chat to the locals. For the more adventurous there may be a guided kayak tour along the coast to waterfalls directly into the sea (weather permitting. The hike is approx. 1 hour for fit walkers. Quite challenging and we join the rest of the group by the river for lunch.) Friday: We reach the most northern island of Lau—Wailagilala. See the remains of a disused lighthouse, or explore the abun- dant fish life whilst snorkelling. Saturday: Qilaqila, at the northwest end of Vanuabalavu, is known for its pristine waters and mushroom shaped islands. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise Aboard MV Reef Endeavour

The Senior Newspaper and Travelrite International invite you to join them on the 2022 FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise aboard MV Reef Endeavour Denarau, Lau Islands and Kadavu Islands, Fiji 22 October to 5 November 2022 SENFIJI21 – GLG0740 FIJIAN ISLANDS Discovery Cruise If you want to experience the real Fiji, join TOUR HIGHLIGHTS us on MV Reef Endeavour as we explore • Three nights at a Luxury Resort on Denarau the Lau Islands and Kadavu; a beautiful and Island, Fiji remote region rarely seen by tourists. A • Discover islands and reefs rarely visited by visit to this region offers a once in a lifetime tourists aboard MV Reef Explorer experience to a select few travellers, visiting • Visit the amazing Bay of Islands – a magnificent turquoise bays and remote villages where location with many limestone islands they only see a supply boat once a month. • Be treated to a song and dance by children of all ages from a local village • Snorkelling, glass bottom boat & dive opportunities daily Cruise highlights include a swim at a waterfall, exploring • Swim in some of the most pristine and clear old ruins, snorkelling untouched reefs and getting waters that the Lau group has to offer up close with nesting turtles. You’ll also explore the • Island Night, kava, meke & lovo feast caves, reefs and lagoons of Qilaqila renowned for its mushroom-shaped islands, and the central lake on uninhabited Vuaqava island where you’ll find turtles, TOUR ITINERARY snakes and amazing bird life. Best of all, you’ll be DAY 1: Saturday 22 October 2022 Depart/Denarau, Fiji welcomed and entertained by the friendly people of this Our holiday begins with our flight to Nadi, Fiji. -

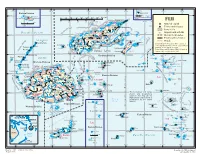

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Filling the Gaps: Identifying Candidate Sites to Expand Fiji's National Protected Area Network

Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20-21 September 2010 Stacy Jupiter1, Kasaqa Tora2, Morena Mills3, Rebecca Weeks1,3, Vanessa Adams3, Ingrid Qauqau1, Alumeci Nakeke4, Thomas Tui4, Yashika Nand1, Naushad Yakub1 1 Wildlife Conservation Society Fiji Country Program 2 National Trust of Fiji 3 ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University 4 SeaWeb Asia-Pacific Program This work was supported by an Early Action Grant to the national Protected Area Committee from UNDP‐GEF and a grant to the Wildlife Conservation Society from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation (#10‐94985‐000‐GSS) © 2011 Wildlife Conservation Society This document to be cited as: Jupiter S, Tora K, Mills M, Weeks R, Adams V, Qauqau I, Nakeke A, Tui T, Nand Y, Yakub N (2011) Filling the gaps: identifying candidate sites to expand Fiji's national protected area network. Outcomes report from provincial planning meeting, 20‐21 September 2010. Wildlife Conservation Society, Suva, Fiji, 65 pp. Executive Summary The Fiji national Protected Area Committee (PAC) was established in 2008 under section 8(2) of Fiji's Environment Management Act 2005 in order to advance Fiji's commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)'s Programme of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA). To date, the PAC has: established national targets for conservation and management; collated existing and new data on species and habitats; identified current protected area boundaries; and determined how much of Fiji's biodiversity is currently protected through terrestrial and marine gap analyses. -

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji: landscapes, hotspots and ecological processes D avid O lson,Linda F arley,Alex P atrick,Dick W atling,Marika T uiwawa V ilikesa M asibalavu,Lemeki L enoa,Alivereti B ogiva,Ingrid Q auqau J ames A therton,Akanisi C aginitoba,Moala T okota’a,Sunil P rasad W aisea N aisilisili,Alipate R aikabula,Kinikoto M ailautoka C raig M orley and T homas A llnutt Abstract Fiji’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action goal of protecting 40% of remaining natural forests to Plan encourages refinements to conservation priorities based achieve the goals of the National Biodiversity Strategy and on analyses of new information. Here we propose a network Action Plan and sustain ecosystem services for Fijian com- of Priority Forests for Conservation based on a synthesis of munities and economies. new studies and data that have become available since Keywords Conservation priorities, ecosystem services, Fiji, legislation of the Action Plan in 2001. For selection of Pri- forest conservation, national biodiversity strategy, Oceania, ority Forests we considered minimum-area requirements protected area network, representation for some native species, representation goals for Fiji’s habitats and species assemblages, key ecological processes This paper contains supplementary material that can be and the practical realities of conservation areas in Fiji. found online at http://journals.cambridge.org Forty Priority Forests that cover 23% of Fiji’s total land area and 58% of Fiji’s remaining native forest were iden- tified. -

Vanua Levu Vita Levu Suva

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 0 10 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Coral reefs Sasa Nasea l Cobia e n n Airports and airfields Pacific Ocean Navidamu Rabi a Labasa e y Nailou h v a C 16° 30’ Natua ro B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld ka o Nabiti Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu Bua conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua a parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. s Yandua Nadivakarua Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Nanuku Passage Viwa Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata tu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Wayalevu Malake - Vanua Balavu I- Nasau N r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna C H Kuata Tavua Vaileka h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Ra n Mago N Sorokoba n Lomaiviti -

Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji

R BAPID IOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT SURVEY OF SOUTHERN LAU, FIJI BI ODIVERSITY C ONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES 22 © 2013 Cnes/Spot Image BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL SERIES Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern 22 Lau, Fiji Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series is published by: Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) and Conservation International Pacific Islands Program (CI-Pacific) PO Box 2035, Apia, Samoa T: + 685 21593 E: [email protected] W: www.conservation.org The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. A fundamental goal is to ensure civil society is engaged in biodiversity conservation. Conservation International Pacific Islands Program. 2013. Biodiversity Conservation Lessons Learned Technical Series 22: Rapid Biological Assessment Survey of Southern Lau, Fiji. Conservation International, Apia, Samoa Authors: Marika Tuiwawa & Prof. William Aalbersberg, Institute of Applied Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. Design/Production: Joanne Aitken, The Little Design Company, www.thelittledesigncompany.com Cover Photograph: Fiji and the Lau Island group. Source: Google Earth. Series Editor: Leilani Duffy, Conservation International Pacific Islands Program Conservation International is a private, non-profit organization exempt from federal income tax under section 501c(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. OUR MISSION Building upon a strong foundation of science, partnership and field demonstration, Conservation International empowers societies to responsibly and sustainably care for nature for the well-being of humanity. ISBN 978-982-9130-22-8 © 2013 Conservation International All rights reserved. -

Fiji Islands

i ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK TA: 6039-REG REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS: COUNTRY ENVIRONMENTAL ANALYSIS Mainstreaming Environmental Considerations in Economic and Development Planning Processes (FINAL DRAFT) Prepared by: James T. Berdach February 2005 The views expressed in this document are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent positions of the Asian Development Bank or the Government of the Republic of the Fiji Islands. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 November 2004) Currency Unit – Fiji Dollars (FJD) FJD 1.00 = $0.5955 $1.00 = FJD 1.6793 ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADTA – advisory technical assistance ALTA – Agricultural Landlord Tenant Act BOD – biochemical oxygen demand CDM – Clean Development Mechanism CEA – Country Environmental Analysis CHARM – Comprehensive Hazard and Risk Management CLIMAP – Climate Change Adaptation Program for the Pacific CSP – Country Strategy and Program CSPU – Country Strategy and Program Update DOE – Department of Environment DPP – Director of Public Prosecution DRRF – Disaster Relief and Rehabilitation Fund EEZ – Exclusive Economic Zone EIA – environmental impact assessment EMB – Environment Management Bill EU – European Union FBSAP – Fiji Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan FEA – Fiji Energy Authority FEU – Forestry Economics Unit FIMSA – Fiji Islands Marine Safety Administration FLMMA – Fiji Locally Managed Marine Area FRUP – Fiji Road Upgrading Project FSC – Fiji Sugar Corporation GDP – gross domestic product GEF – Global Environment Facility GHG – greenhouse -

Fiji : State of Birds, 2013 / Dick Watling

FIJI | State of Birds | 2013 A Guide for Conservationists, atureFiji Policymakers and Communities MareqetiViti USP Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Watling, Dick Fiji : state of birds, 2013 / Dick Watling. – Suva, Fiji : Nature Fiji-MareqetiViti, 2013. 44 p. ; 21 cm. ISBN 978-982-9131-02-7 1. Birds—Fiji. I. NatureFiji-MareqetiViti. II. Title. QL694.F5W34 2013 598.099611 Copyright © 2013 NatureFiji-MareqetiViti NatureFiji-MareqetiViti, 14 Hamilton-Beattie Street (off Service Street), Suva, Fiji Islands. p: 679 310 0598 e: [email protected] www.naturefiji.org Copyright © in all photographs published in this book is invested in those photographers whose names appear adjacent to their images. Text by Dick Watling. Designed by James de Clifford. Artwork by Streamline Creative Ltd, New Zealand. Printed in Fiji. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher. However, some limited usage is permitted for educational and non-commercial purposes only, including private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting. Front/back cover: Orange-breasted Myzomela Myzomela jugularis. This endemic Fijian bird is equally common in State; Pressure; Response suburban gardens and mountain forest © Mark Fraser. Inside front/inside back cover: Crested Tern Sterna bergii Many issues affecting Fiji’s birds also impact Fiji’s biodiversity in has strong coastal affinities, though it is rarely seen far general. This report examines why our birds and biodoversity are from land. Its habitat range extends from the West, South important (Introduction), what we know about the changing state and Central Pacific to the Indian Ocean © Mark Fraser. -

Recommandé Par

Fidji COUNTRY GUIDE www.petitfute.com recommandé par 2017_PubQuotaTripV2_vectorise.indd 1 12/05/2017 11:56 EDITION Directeurs de collection et auteurs : Dominique AUZIAS et Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE Bula Fiji ! Auteurs : Manon CHAUVIN, Camille RENEVOT, Diane CLAYTON, Jean-Paul LABOURDETTE, Dominique AUZIAS et alter Directeur Editorial : Stéphan SZEREMETA Fidji s’étend de la belle et grande Viti Levu à Vanua Levu, Rédaction Monde : Caroline MICHELOT, en passant par l’archipel bien gardé des Lomaitivi sans Morgane VESLIN, Pierre-Yves SOUCHET, Jimmy POSTOLLEC et Elvane SAHIN oublier Taveuni, ni bien sûr les îles Mamanucas et Yasawas, Rédaction France : Elisabeth COL, où s’exaucent nos rêves d’îlots paradisiaques. Ce pays Silvia FOLIGNO et Tony DE SOUSA compte plus de 300 îles incroyables et variées, tant par FABRICATION leur géographie que par leur culture. Fidji est un pays Responsable Studio : Sophie LECHERTIER aux couleurs vives, où le soleil brille toute l’année, où assistée de Romain AUDREN l’air est pur et où les eaux sont claires et limpides. Mais Maquette et Montage : Julie BORDES, Sandrine MECKING, Delphine PAGANO imaginez maintenant, le sourire sur le visage de chaque et Laurie PILLOIS enfant, l’échange facile avec tous, des « bula » joyeux Iconographie : Anne DIOT et des éclats de rire rimant chacune de vos rencontres. Cartographie : Julien DOUCET Imaginez un peuple ouvert, fier de sa culture et de ses WEB ET NUMERIQUE terres. Un peuple chez qui tout se partage, où l’humanité Directeur Web : Louis GENEAU de LAMARLIERE est là et bien -

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji

Priority Forests for Conservation in Fiji: landscapes, hotspots and ecological processes D avid O lson,Linda F arley,Alex P atrick,Dick W atling,Marika T uiwawa V ilikesa M asibalavu,Lemeki L enoa,Alivereti B ogiva,Ingrid Q auqau J ames A therton,Akanisi C aginitoba,Moala T okota’a,Sunil P rasad W aisea N aisilisili,Alipate R aikabula,Kinikoto M ailautoka C raig M orley and T homas A llnutt Abstract Fiji’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action goal of protecting 40% of remaining natural forests to Plan encourages refinements to conservation priorities based achieve the goals of the National Biodiversity Strategy and on analyses of new information. Here we propose a network Action Plan and sustain ecosystem services for Fijian com- of Priority Forests for Conservation based on a synthesis of munities and economies. new studies and data that have become available since Keywords Conservation priorities, ecosystem services, Fiji, legislation of the Action Plan in 2001. For selection of Pri- forest conservation, national biodiversity strategy, Oceania, ority Forests we considered minimum-area requirements protected area network, representation for some native species, representation goals for Fiji’s habitats and species assemblages, key ecological processes This paper contains supplementary material that can be and the practical realities of conservation areas in Fiji. found online at http://journals.cambridge.org Forty Priority Forests that cover 23% of Fiji’s total land area and 58% of Fiji’s remaining native forest were iden- tified.