Identification Guide to Autumn Wagtails by Iain Livingstone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status and Occurrence of White Wagtail (Motacilla Alba) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of White Wagtail (Motacilla alba) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Don Cecile. Introduction and Distribution The White Wagtail (Motacilla alba) is a small passerine species that is found throughout the Old World: breeding from the southeastern tip of Greenland, and Iceland; from Great Britain, south to Morocco, across all of Europe; throughout western Russia, all of Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, along the Himalayas east into southern China, Mongolia, all of eastern Russia, and into western coastal areas of Alaska (Alstrom and Mild 2003). The White Wagtail winters from Great Britain, south throughout western Europe from Germany to Spain, east through Italy, Greece, into Turkey and the Middle East, south into the northern countries of Africa, east to Saudi Arabia, throughout Iraq, Iran, into India, east throughout south east Asia north through southern China, the northern Philippines, Taiwan and Japan (Alstrom and Mild 2003). There are 9 recognized subspecies found throughout the range of the White Wagtail with only 3 having been recorded in North America (Alstrom and Mild 2003). The nominate subspecies of White Wagtail (Motacilla alba alba) has occurred accidentally along the east coast of North America (Hamilton et al. 2007, Dunn and Alderfer 2011). In western North America, the White Wagtails that occur are from the subspecies that make up the (Motacilla alba ocularis/lugens) complex (Sibley 2000, Dunn and Alderfer 2011). These two subspecies were once separate species with one called White Wagtail (Motacilla alba ocularis) and the other called Black-backed Wagtail (Motacilla alba lugens) (Alstrom and Mild 2003). In 2005, the AOU officially lumped Black- backed Wagtail back with White Wagtail and now the Black-backed Wagtail is considered a subspecies of the White Wagtail (Banks et al. -

Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director

Center for Tropical Research October 2006 Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director Avian Influenza Virus – An Overview The UCLA Center for Tropical Research (CTR) is at the forefront of research and surveillance efforts on avian influenza virus (bird flu or avian flu) in wild birds. CTR has led avian influenza survey efforts on migratory landbirds in both North America and Central Africa since spring 2006. We have recently been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct a large study in North, Central, and South America on the effects of bird migration and human habitat disturbance on the distribution and transmission of bird flu. These studies take advantage of our unique collaboration with the major bird banding station networks in the Americas, our extensive experience in avian field research in Central Africa, and UCLA’s unique resources and expertise in infectious diseases though the UCLA School of Public Health and its Department of Epidemiology. CTR has ongoing collaborations with four landbird monitoring networks: the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) network, the Monitoring Avian Winter Survival (MAWS) network, and the Monitoreo de Sobrevivencia Invernal - Monitoring Overwintering Survival (MoSI) network, all led by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), and the Landbird Migration Monitoring Network of the Americas (LaMMNA), led by the Redwood Sciences Laboratory (U.S. Forest Service). Bird flu has shot to the public’s consciousness with the recent outbreaks of a highly virulent subtype of avian influenza A virus (H5N1) that has recently occurred in Asia, Africa, and Europe. -

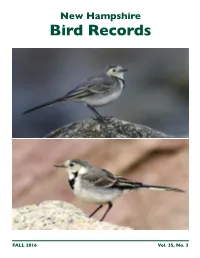

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records FALL 2016 Vol. 35, No. 3 IN HONOR OF Rob Woodward his issue of New Hampshire TBird Records with its color cover is sponsored by friends of Rob Woodward in appreciation of NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS all he’s done for birds and birders VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3 FALL 2016 in New Hampshire. Rob Woodward leading a field trip at MANAGING EDITOR the Birch Street Community Gardens Rebecca Suomala in Concord (10-8-2016) and counting 603-224-9909 X309, migrating nighthawks at the Capital [email protected] Commons Garage (8-18-2016, with a rainbow behind him). TEXT EDITOR Dan Hubbard In This Issue SEASON EDITORS Rob Woodward Tries to Leave New Hampshire Behind ...........................................................1 Eric Masterson, Spring Chad Witko, Summer Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2016 by Ben Griffith and Lauren Kras ................2 Winter Jim Sparrell/Katie Towler, Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2016 Update by Rob Woodward ..............................25 LAYOUT Fall 2016 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report by Iain MacLeod ...................................26 Kathy McBride Field Notes compiled by Kathryn Frieden and Rebecca Suomala PUBLICATION ASSISTANT Loon Freed From Fishing Line in Pittsburg by Tricia Lavallee ..........................................30 Kathryn Frieden Osprey vs. Bald Eagle by Fran Keenan .............................................................................31 -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Thirteenth Report of the California Bird Records Committee

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 23, Number 3, 1992 THIRTEENTH REPORT OF THE CALIFORNIA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE PETER PYLE, Point Reyes Bird Observatory,4990 ShorelineHighway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 GUY McCASKIE, 954 GroveStreet, Imperial Beach, California 91932 Western Field Ornithologistsand the California Bird RecordsCom- mittee are againpleased to thank Bushnell,a divisionof Bausch& Lomb, for its continued generoussupport in sponsoringthe publication of our reports. This report contains376 recordsof 96 speciesthat have recentlybeen reviewedby the California Bird RecordsCommittee (hereafter,the CBRC or the Committee).The 321 acceptedrecords of 83 speciesand 55 rejectedrecords of 36 speciesrepresent an 85.4% acceptancerate. Re- portswere receivedfrom 37 of the state's58 counties,including all coastal counties.As in past years, the best-representedcounties were San Fran- cisco(44 acceptedrecords including 36 from SoutheastFarallon Island), San Diego (35), Santa Barbara (31), Monterey (25) and Marin (21). Al- though the dates of the records extend from 30 August 1969 to 9 September1989, the great majorityof them (339) are from 1 December 1986 to 28 February 1989, representinga very high percentageof the recordsof CBRC Review-Listspecies (see below) from Californiapublished in American Birds(hereafter AB) duringthis period. In 1991, the Commit- tee received 236 records, an increase of 15 from 1990. The Committee greatly appreciatesthe increasinginterest by the birding communityin submittingdocumentation of rare birdsin the state. We continueto encouragebirders and ornithologiststo support the CBRC processby submittingwritten reports and/or photographsto Michael A. Patten, CBRC Secretary, P.O. Box 8612, Riverside,CA 92515. We believethat the decisionsof the CBRC are highly qualified, standardizedassessments of the validityof recordsbut not alwaysthe final word on whether or not an identification is correct. -

Entirely Electronic Journal Published Annually by the Institute for Bird Populations

BIRD POPULATIONS A journal of global avian demography and biogeography Volume 13 2014 Published annually by The Institute for Bird Populations BIRD POPULATIONS A journal of global avian demography and biogeography Published by The Institute for Bird Populations Editor: DAVID G. AINLEY, H.T. Harvey & Associates, 983 University Avenue, Bldg D, Los Gatos, CA 95032; 415-272-9499; [email protected] Managing Editor: DAVID F. DESANTE, The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, CA 94956-1346; 415-663-2052; 415-663-9482 fax; [email protected] Spanish Translation of Abstracts: BORJA MILA, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, Madrid 28006, Spain; [email protected] Layout and Typesetting: PRISCILLA YOCOM, 5018 Albridal Way, San Ramon, CA 94582 THE INSTITUTE FOR BIRD POPULATIONS A tax-exempt California nonprofit corporation established in 1989 and dedicated to fostering a global approach to research and the dissemination of information on changes in bird populations. President: DAVID F. DESANTE , P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, CA 94956 Secretary-Treasurer: STEPHEN M. ALLAN, 962 Mistletoe Loop N, Keizer, OR 97303 Directors: CORDELL GREEN, IVAN SAMUELS, RODNEY B. SIEGEL, and DAN TOMPKINS All persons interested in birds are invited to join The Institute for Bird Populations. Individual membership dues are $35 per year. Institutional memberships are $50 per year; student and senior memberships are $15 per year. Please send check or money order (in U.S. dollars) payable to The Institute for Bird Populations, along with complete name, address, and email address to: The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. -

References 'East Siberian Wagtail' (White Wagtail) Motacilla Alba

Correspondence 95 The White-tailed Flycatcher is not a widespread species in the (de Rouw 2019). It was not shy, enabling PdR to digiscope it Eastern Himalayas; possibly breeding in south-eastern Arunachal [117]. We did not realize the importance of the sighting until later and wintering in adjacent Upper Assam and the Patkai Hills. It in the evening, when, while reviewing our daily sightings against has been reported from Meghalaya, Manipur, and Mizoram (Ali Grimmett et al. (1998) and Rasmussen & Anderton (2012), we & Ripley 1987; Grimmett et al. 2011; Rasmussen & Anderton realized that ocularis is only supposed to winter in Northeast- 2012; Clement 2019; eBird 2019). It is listed for Nagaland in India. From the only digiscoped image available, our bird can Choudhury (2001) without any details of status and abundance, be seen to be grey-backed and to have a distinct eye-stripe, as well as Choudhury (2003) with status given as ‘unknown’. amongst other features. The bird is a male but its age cannot be Its presence in the Patkai Hills and further southwards, in the determined with certainty. Mizo Hills might have lead to the speculation that it would occur in the Naga Hills as well. Choudhury (2003, 2005) must have been the source of this being listed in several online checklists for Nagaland (Grewal 2010; Lepage 2019). Hence, this appears to be the first definitive evidence of it occurring in the Naga Hills. I would like to thank Rajneesh Suvarna for confirmation the Peter W. W. de Rouw identification of the bird on a private WhatsApp Web group, my wife, Nisha Sharma, who pointed out the bird to me, and GoingWild LLP for logistic support during my tour. -

A Survey of the Autumn 2009 and Spring 2010 Bird Migrations at Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China JOHN D

FORKTAIL 32 (2016): 14–25 A survey of the autumn 2009 and spring 2010 bird migrations at Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China JOHN D. FARRINGTON Between July 2009 and May 2010 an extensive ornithological survey was carried out at Lhasa, Tibet Autonomous Region, China, in the city wetland complex focused on the Lhalu Wetland National Nature Reserve and the adjacent Lhalu and Lhasa rivers wetland complex. Counts were made along a series of transects on a weekly basis, generally consisting of two full field days each week. During the survey 113 avian species were seen, with arrival and departure dates of most migratory species being determined: 21 species were summer visitors, 22 winter visitors, 22 passage migrants, 12 altitudinal migrants, 3 vagrants, 1 probable escapee and 32 residents. Autumn migration began in early September, continued until late December and was of particular interest for shorebird passage. Spring migration began in mid-February and was ongoing in May when the survey was concluded; it was of particular interest for passage waterfowl. A review of, and comparison with, historical records was made and a number of species that have undergone significant declines since the 1940s have been identified. Sightings of Baikal Teal Sibirionetta formosa, Little Egret Egretta garzetta, Lesser Grey Shrike Lanius minor, Rufous-vented Tit Periparus rubidiventris and Red-throated Pipit Anthus cervinus are believed to be the first in the Lhasa city area. The Lhalu Wetland National Nature Reserve and the adjacent Lhalu River and Lhasa River wetland complex appear to qualify for designation as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance under Criterion 6 based on their Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea population. -

Western Yellow Wagtail

# 014 Bird-o-soar 21 March 2018 WESTERN YELLOW WAGTAIL Photographic record of leucistic Motacilla flava from Porbandar, Gujarat IUCN Red List: Global: Least Concern (Birdlife International 2017) Aberrantly coloured Western Yellow Wagtail (Photo: Dhaval Vargiya) The sighting of Leucistic Western yellow wagtail Motacilla flava at Karly II Wetland (21.6320300N & 69.6508750E) of Aves [Class of Birds] Mokarsagar Wetland Complex of Porbandar District, Gujarat, on 22 March 2015, is probably the first known published record of Passeriformes [Order of perching birds] leucism in Western Yellow Wagtail from India. Records of colour Motacillidae aberrations in Indian birds between 1886–2015 have been already [Family of Pipits and published but do not include Wagtail sp. (Mahabal et al. 2016). Wagtails] Western Yellow Wagtail is a common winter visitor to Motacilla flava [Western Yellow Wagtail] Gujarat and seen in suitable habitats across the state (Ganpule 2016). Head, nape and ear-coverts are dark slate-grey, sometimes Species described by Linnaeus in 1758 with a trace of a white supercilium. Back is olive and wings brown with two yellowish bars. Tail is dark brown with white outer edge. Zoo’s Print Vol. 33 | No. 3 37 # 014 Bird-o-soar 21 March 2018 The bird is bright yellow from chin to under Global Distribution: Native: Afghanistan; Albania; Algeria; Angola; Armenia; Austria; tail-coverts. Winter plumage is duller, with Azerbaijan; Bahrain; Bangladesh; Belarus; Belgium; Benin; Bhutan; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Botswana; Bulgaria; Burkina Faso; the grey on head mixed with olive. Sexes Burundi; Cameroon; Central African Republic; Chad; China; Congo; Congo, The Democratic Republic of the; Côte d’Ivoire; Croatia; are more or less alike. -

Ticks (Ixodoidea) on Birds Migrating from Africa to Europe and Asia* HARRY HOOGSTRAAL,1 MAKRAM N

Bull. Org. mond. Sante ) 1961, 24, 197-212 Bull. Wid Huth Org. j Ticks (Ixodoidea) on Birds Migrating from Africa to Europe and Asia* HARRY HOOGSTRAAL,1 MAKRAM N. KAISER,1 MELVIN A. TRAYLOR 2 SOBHY GABER 1 & EZZAT GUINDY 1 Hyalomma marginatum marginatum ofEurope and Asia and H. marginatum rufipes ofAfrica, both reservoirs and vectors oforganisms pathogenic to humans and animals, have not infrequently beenfound as incidental specimens or establishedpopulationsfarfrom their normal endemic geographical boundaries. Owing to ticks' unique ability to transmit or harbourfor longperiods a variety ofpathogens of man andanimals, theirpotential epidemio- logical role is suspected wherever they occur. Evidence that birds, in themselves hosts of several viruses causing human disease, actually transport the African H. marginatum rufipes northwards was obtained in Egypt by capture of infested migrants during spring passagefrom East Africa to Europe and Asia. Between 1956 and 1960, 340 birds represent- ing 22 forms (species and subspecies) were found infested by 1025 immature ticks, all but seven of which were or appear to be H. marginatum rufipes. The period ofattachment of immature stages ofrufipes to their host is sufficient to suggest that many of these ticks are carried some distance into Europe and Asia. INTRODUCTION The role of northward migrating birds in long- these ticks are vectors of human and animal diseases. distance and large-scale transport of immature The ability of numerous tick species to transmit or stages of the African tick, Hyalomma marginatum to harbour for long periods (or both) a variety of rufipes Koch, 1844, reported herein, has epidemio- pathogenic organisms, especially viruses and rickett- logical implications requiring further study in a siae, causes them to be suspect as reservoirs of number of disciplines and geographical areas. -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG. -

Status and Identification of Forms of White Wagtail in Western North America

Status and Identification of forms of White Wagtail in Western North America JOSEPH MORLAN Two forms of White Wagtail (two full species, according to Soviet research) occur in Alaska: one breeds there, one is a rare stray. Which is more likely south of Alaska? This thorough investigation produced some astonishing answers ON THE MORNINGof 22 May 1980 Bill Lenarz and Sue Smith found a White Wagtail at the U.S. Department of Commerce's National Marine Fisheries laboratory on Paradise Drive in Tiburon, Marin County, California. Bill called me in time, and I had an opportunity to observe the wagtail at very close range for more than an hour. I was astounded to see that its back was mostly black, a characteristic of the race Motacil/a alba lugens which had never been positively recorded in North America south of Alaska. The gray-backed northeast Siberian race, M. a. ocularis, a rare breeder in western Alaska, had been reported several times on the west coast south of Alaska. The Tiburon wagtail sang a long, elaborate, very soft song of mostly slurred notes while it fed among rotting planks of an old broken-down wharf. It fed slowly, picking insects, bobbing and wagging its tail. In flight it gave a loud penetrating "tchiZ1;ick" call. Leonard Compagno took many black-and-white photographs (Figure 1), and Phil Schaeffer took additional color photographs. The thin black line through the eye and the white face are found only in lugens and ocularis. No other races of M. alba show this feature. This, along with extensive black clouding on the scapulars and back, identified this bird as /ugens.