Status and Occurrence of White Wagtail (Motacilla Alba) in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Pipit Anthus Rubescens

American Pipit Anthus rubescens Folk Name: Water Pipit, Titlark, Skylark, Brownlark Status: Migrant, Winter Visitor Abundance: Uncommon to Common Habitat: Bare-ground, short-grass fields, pastures, lawns, mudflats The American Pipit was once called the Water Pipit and the Titlark. For a time, it was called the Skylark, similar to the Eurasian Skylark—a famous soaring songbird. However, the two are not closely related. “What of the word ‘lark,’ as meaning a frolic? The Anglo- Saxon word ‘lark,’ meaning play. So a sky lark is the bird that frolics, or plays, or rejoices, or ‘larks,’ in the air or s k y.” — The People’s Press, Winston-Salem, March 6, 1857 The American Pipit is a fairly nondescript winter In the late 1870s, Leverett Loomis considered the visitor usually encountered in small loose flocks foraging “Brownlark” as an “abundant” winter resident in Chester on the ground in large open areas of very short grass, County, SC. In North Carolina in 1939, C. S. Brimley mudflats, pasture, or dirt fields. It has a distinctive flight noted that “[r]ecords of Pipits…seem to be totally lacking call that sounds very much like pip pit. At 6 ½ inches, the from the Piedmont region” and requested additional pipit is slightly smaller than our common bluebird. It is pipit records be submitted for use in the second edition gray brown above, and its underparts are buff white and of Birds of North Carolina. William McIlwaine responded streaked. Look closely for a light line above the eye and to Brimley’s request with a list of American Pipit flocks white outer tail feathers. -

SPRAGUE's PIPIT (Anthus Spragueii) STATUS: USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern; No Endangered Species Act Status. SPECIES DE

SPRAGUE’S PIPIT (Anthus spragueii) STATUS: USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern; No Endangered Species Act status. SPECIES DESCRIPTION: The Sprague's pipit is a small passerine of the family Motacillidae that is endemic to the North American grassland. The Sprague's pipit is about 10-15 centimeters (3.9-5.9 inches) in length, and weighs 22-26 grams (0.8-0.9 ounce), with buff and blackish streaking on the crown, nape, and underparts. It has a plain buffy face with a large eye-ring. The bill is relatively short, narrow, and straight with a blackish upper mandible. The lower mandible is pale with a blackish tip. The wings and tail have two indistinct wing-bars, outer tail feathers are mostly white. Legs are yellowish to pale pinkish-brown. Juveniles are slightly smaller, but similar to adults, with black spotting rather than streaking. Sprague’s pipit is most similar in appearance to the American pipit, which has less streaking (becomes uniformly gray in spring) and dark brown to blackish legs. HABITAT: Nests in short-grass plains, mixed grass prairie, alkaline meadows, and wet meadows where the vegetation is intermediate in height and provides dense cover. More common in native grasslands than areas with introduced grasses. Native grass fields are rare in Arizona but cultivated, dry Bermuda grass, alfalfa fields mixed with patches of dry grass or fallow fields appear to support the species during wintering. They will not use mowed or burned areas until the vegetation has had a chance to grow. RANGE: Breeding range includes portions of south-central Canada, North Dakota, northern portions of South Dakota, Montana, and Minnesota. -

Meadow Pipit Scientific Name: Anthus Pratensis Irish Name: Riabhóg Mhóna by Lewis Gospel

Bird Life Meadow Pipit Scientific Name: Anthus pratensis Irish Name: Riabhóg Mhóna By Lewis Gospel he meadow pipit is a small bird and is part of the pipit T family. As the first half of its name suggests it can be found in areas of wide open country. The second half of its name dates back all the way to 1768, when it used to be called a tit lark! It is a hard species to tell apart from others in the pipit family. If you look closely it has a thin bill and white, pale pinkish yellow legs with a hind claw at the back of the feet. This claw is a lot longer than its other claws. It mostly likes to eat on the ground and its favourite food in summer are insects and wriggling earthworms. In winter it likes to eat seeds and berries. These give it plenty of energy when other food is not as plentiful. Photos: © Robbie Murphy © Robbie Photos: How you can spot it! If you find yourself in any grassland, heath or moor listen out for a squeaky 'tsip'-like call as the Meadow Pipit travels in little flocks. Be sure to look where you are walking, as these little birds likes to nest on the ground. If disturbed they will rise in ones or twos, or in a little body or group. The Meadow Pipit looks a lot like its close relative the Tree Pipit, and in Ireland there is a subspecies called ‘Anthus pratensis whistleri‘ that is a little darker than the ones you find in other countries in Europe. -

Birds of Anchorage Checklist

ACCIDENTAL, CASUAL, UNSUBSTANTIATED KEY THRUSHES J F M A M J J A S O N D n Casual: Occasionally seen, but not every year Northern Wheatear N n Accidental: Only one or two ever seen here Townsend’s Solitaire N X Unsubstantiated: no photographic or sample evidence to support sighting Gray-cheeked Thrush N W Listed on the Audubon Alaska WatchList of declining or threatened species Birds of Swainson’s Thrush N Hermit Thrush N Spring: March 16–May 31, Summer: June 1–July 31, American Robin N Fall: August 1–November 30, Winter: December 1–March 15 Anchorage, Alaska Varied Thrush N W STARLINGS SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER SPECIES SPECIES SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER European Starling N CHECKLIST Ross's Goose Vaux's Swift PIPITS Emperor Goose W Anna's Hummingbird The Anchorage area offers a surprising American Pipit N Cinnamon Teal Costa's Hummingbird Tufted Duck Red-breasted Sapsucker WAXWINGS diversity of habitat from tidal mudflats along Steller's Eider W Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Bohemian Waxwing N Common Eider W Willow Flycatcher the coast to alpine habitat in the Chugach BUNTINGS Ruddy Duck Least Flycatcher John Schoen Lapland Longspur Pied-billed Grebe Hammond's Flycatcher Mountains bordering the city. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel Eastern Kingbird BOHEMIAN WAXWING Snow Bunting N Leach's Storm-Petrel Western Kingbird WARBLERS Pelagic Cormorant Brown Shrike Red-faced Cormorant W Cassin's Vireo Northern Waterthrush N For more information on Alaska bird festivals Orange-crowned Warbler N Great Egret Warbling Vireo Swainson's Hawk Red-eyed Vireo and birding maps for Anchorage, Fairbanks, Yellow Warbler N American Coot Purple Martin and Kodiak, contact Audubon Alaska at Blackpoll Warbler N W Sora Pacific Wren www.AudubonAlaska.org or 907-276-7034. -

The Evolutionary History of the White Wagtail Species Complex, (Passeriformes: Motacillidae: Motacilla Alba)

Contributions to Zoology 88 (2019) 257-276 CTOZ brill.com/ctoz The evolutionary history of the white wagtail species complex, (Passeriformes: Motacillidae: Motacilla alba) Maliheh Pirayesh Shirazinejad Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran Mansour Aliabadian Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran Research Department of Zoological Innovations, Institute of Applied Zoology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran [email protected] Omid Mirshamsi Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran Research Department of Zoological Innovations, Institute of Applied Zoology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran Abstract The white wagtail (Motacilla alba) species complex with its distinctive plumage in separate geographical areas can serve as a model to test evolutionary hypotheses. Its extensive variety in plumage, despite the genetic similarity between taxa, and the evolutionary events connected to this variety are poorly under- stood. Therefore we sampled in the breeding range of the white wagtail: 338 individuals were analyzed from 74 areas in the Palearctic and Mediterranean. We studied the white wagtail complex based on two mitochondrial DNA markers to make inferences about the evolutionary history. Our phylogenetic trees highlight mtDNA sequences (ND2, CR), and one nuclear marker (CHD1Z), which partly correspond to earlier described clades: the northern Palearctic (clade N); eastern and central Asia (clade SE); south- western Asia west to the British Isles (clade SW); and Morocco (clade M). The divergence of all clades occurred during the Pleistocene. We also used ecological niche modelling for three genetic lineages (ex- cluding clade M); results showed congruence between niche and phylogenetic divergence in these clades. -

The Field Identification of North American Pipits Ben King Illustrated by Peter Hayman and Pieter Prall

The field identification of North American pipits Ben King Illustrated by Peter Hayman and Pieter Prall LTHOUGHTHEWATER PIPIT (Anthus ground in open country. However, the in this paper. inoletta) and the Sprague's Pipit two speciesof tree-pipits use trees for (Antbus spragueit)are fairly easy to rec- singing and refuge and are often in NCEABIRD HAS been recognized asa ogmze using the current popular field wooded areas. pipit, the first thing to checkis the guides, the five species more recently All the pipits discussedin the paper, ground color of the back. Is it brown added to the North American list are except perhaps the Sprague's, move (what shade?), olive, or gray? Then note more difficult to identify and sometimes their tails in a peculiarpumping motion, the black streaks on the back. Are they present a real field challenge. The field down and then up. Some species broad or narrow, sharply or vaguely de- •dentffication of these latter specieshas "pump" their tails more than others. fined, conspicuousor faint? How exten- not yet been adequatelydealt with in the This tail motion is often referred to as sive are they? Then check for pale North American literature. However, "wagging." While the term "wag" does streaks on the back. Are there none, much field work on the identification of include up and down motion as well as two, four, many? What color are they-- pipits has been done in the last few side to side movement, it is better to use whitish, buff, brownish buff? Are they years, especially in Alaska and the the more specificterm "pump" which is conspicuousor faint? Discerningthese Urnted Kingdom. -

Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director

Center for Tropical Research October 2006 Bird Flu Research at the Center for Tropical Research by John Pollinger, CTR Associate Director Avian Influenza Virus – An Overview The UCLA Center for Tropical Research (CTR) is at the forefront of research and surveillance efforts on avian influenza virus (bird flu or avian flu) in wild birds. CTR has led avian influenza survey efforts on migratory landbirds in both North America and Central Africa since spring 2006. We have recently been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to conduct a large study in North, Central, and South America on the effects of bird migration and human habitat disturbance on the distribution and transmission of bird flu. These studies take advantage of our unique collaboration with the major bird banding station networks in the Americas, our extensive experience in avian field research in Central Africa, and UCLA’s unique resources and expertise in infectious diseases though the UCLA School of Public Health and its Department of Epidemiology. CTR has ongoing collaborations with four landbird monitoring networks: the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship (MAPS) network, the Monitoring Avian Winter Survival (MAWS) network, and the Monitoreo de Sobrevivencia Invernal - Monitoring Overwintering Survival (MoSI) network, all led by the Institute for Bird Populations (IBP), and the Landbird Migration Monitoring Network of the Americas (LaMMNA), led by the Redwood Sciences Laboratory (U.S. Forest Service). Bird flu has shot to the public’s consciousness with the recent outbreaks of a highly virulent subtype of avian influenza A virus (H5N1) that has recently occurred in Asia, Africa, and Europe. -

4.3 Passerines If You Want to Increase Passerine 1 Birds on Your Moor, This Fact Sheet Helps You Understand Their Habitat and Diet Requirements

BD1228 Determining Environmentally Sustainable and Economically Viable Grazing Systems for the Restoration and Maintenance of Heather Moorland in England and Wales 4.3 Passerines If you want to increase passerine 1 birds on your moor, this fact sheet helps you understand their habitat and diet requirements. The species covered are the commoner moorland passerines that breed in England and Wales: • Meadow pipit • Skylark • Stonechat • Whinchat • Wheatear • Ring ouzel Broad habitat relationships The study examined detailed abundance relationships for the first five species and coarser presence/absence relationships for the last one above. Several other passerine species breed on moorland, from the widespread wren to the rare and highly localised twite, but these were not included in the study. Meadow pipit and skylark occur widely on moorlands, with the ubiquitous meadow pipit being the most abundant moorland bird. Wheatear, whinchat and stonechat are more restricted in where they are found. They tend to be most abundant at lower altitudes and sometimes on relatively steep ground. Wheatears are often associated with old sheepfolds and stone walls that are often used as nesting sites. The increasingly rare ring ouzel is restricted to steep sided valleys and gullies on moorland, often where crags and scree occur. They are found breeding from the lower ground on moorland, up to altitudes of over 800 m. Biodiversity value & status Of the moorland passerine species considered in this study: • Skylark and ring ouzel are red listed in the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern • Meadow pipit and stonechat are amber listed in the UK’s Birds of Conservation Concern 1 Passerines are songbirds that perch 1 4.3 Passerines • Skylark is on both the England and Welsh Section 74 lists of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of species the conservation of which will be promoted by the Governments [Note: Skylarks are red listed because of declines on lowland farmland largely, and stonechats are amber listed because of an unfavourable conservation status in Europe. -

Wintering Range of Western Yellow Wagtail Motacilla Flava in Africa and Europe in a Historical Perspective

Rivista Italiana di Ornitologia - Research in Ornithology, 90 (1): 3-39, 2020 DOI: 10.4081/rio.2020.430 Wintering range of western yellow wagtail Motacilla flava in Africa and Europe in a historical perspective Flavio Ferlini Abstract - Over the past few centuries, some subspecies of the sporadiche nelle isole dell’Oceano Indiano (Seychelles, Réunion, western yellow wagtail Motacilla flava have shown changes in their ecc.). Assente dalle zone africane prettamente desertiche. A livello reproductive ranges. The aim of this research is to verify if changes di sottospecie nel periodo di studio si sono rilevate le seguenti varia- have occurred also in the wintering range of the species in Africa zioni: aumentata presenza della sottospecie flava in Egitto a partire and Europe from 1848 to 2017. The data, collected through the con- dagli anni 1970; minore ampiezza dell’area di presenza di iberiae sultation of over 840 bibliographic sources, 184 travel reports, 38 rispetto a quanto indicato in pasato, in particolare nell’Africa Occi- databases (including 25 relating to museum collections) and some dentale la sottospecie resta confinata fra la costa dell’Atlantico e website, shows an expansion of the wintering range to the north. il meridiano 2° Ovest anziché raggiungere il 14° Est come prece- The analysis is also extended to the single subspecies (flava, iberiae, dentemente indicato; espansione di cinereocapilla verso occidente, cinereocapilla, flavissima, thunbergi, pygmaea, feldegg, beema, con significative presenze numeriche in Senegal e Gambia; mag- lutea, leucocephala). The factors that can affect the conservation of giore ampiezza dell’areale di flavissima nell’Africa Occidentale the species during wintering are examined and the oversummering con possibili presenze anche in Nigeria e Cameroon (s’ipotizza per range of Motacilla flava in sub-Saharan Africa is also discussed. -

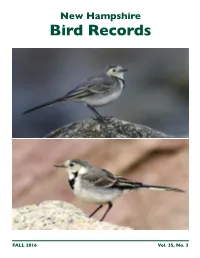

NH Bird Records

New Hampshire Bird Records FALL 2016 Vol. 35, No. 3 IN HONOR OF Rob Woodward his issue of New Hampshire TBird Records with its color cover is sponsored by friends of Rob Woodward in appreciation of NEW HAMPSHIRE BIRD RECORDS all he’s done for birds and birders VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3 FALL 2016 in New Hampshire. Rob Woodward leading a field trip at MANAGING EDITOR the Birch Street Community Gardens Rebecca Suomala in Concord (10-8-2016) and counting 603-224-9909 X309, migrating nighthawks at the Capital [email protected] Commons Garage (8-18-2016, with a rainbow behind him). TEXT EDITOR Dan Hubbard In This Issue SEASON EDITORS Rob Woodward Tries to Leave New Hampshire Behind ...........................................................1 Eric Masterson, Spring Chad Witko, Summer Photo Quiz ...............................................................................................................................1 Lauren Kras/Ben Griffith, Fall Fall Season: August 1 through November 30, 2016 by Ben Griffith and Lauren Kras ................2 Winter Jim Sparrell/Katie Towler, Concord Nighthawk Migration Study – 2016 Update by Rob Woodward ..............................25 LAYOUT Fall 2016 New Hampshire Raptor Migration Report by Iain MacLeod ...................................26 Kathy McBride Field Notes compiled by Kathryn Frieden and Rebecca Suomala PUBLICATION ASSISTANT Loon Freed From Fishing Line in Pittsburg by Tricia Lavallee ..........................................30 Kathryn Frieden Osprey vs. Bald Eagle by Fran Keenan .............................................................................31 -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Pitch for Pipits and Plovers Agribition, 2020

Pitch for Pipits and Plovers Agribition, 2020 Instruction Manual : Pitch for Pipits and Plovers Options for Introduction for Student(s): Option A: Video and Game Show Step 1. Watch the Introduction video on the PCAP YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bveDmBAIZUQ) Step 2. Launch the Game Show Power Point You can download the pdf here: Start on Slide 10. Option 2: Game Show with Introduction from Educator. Launch the Gameshow Power Point. Start at Slide 1. The educator can use this guide to talk about slides 1-9 with the student(s). Playing the Game: 1. Start on Slide 10 (make sure you the presentation is full screen) 2. It is a jeopardy style game. The student can pick the category and the question. “A” questions are easier, “E” questions are the hardest. If playing in a classroom, there is the option to make teams. In playing virtually, one student at a time works. 3. The student will select a category and then A,B,C,D, or E. 4. Read the question on the screen to the student(s) 5. Questions and answers are included in this package. The right answers are highlighted in yellow! 6. Press the “Home” button on the bottom right corner to return to the game 7. Another student can select a question and try to answer. Answered questions will turn purple on the Home screen. Remaining questions are blue. 8. Repeat for about 10 questions, or as time allows. Pitch for Pipits and Plovers Agribition, 2020 Introduction Slide 1: Critical Native Prairie Habitat: • Critical habitat is what is needed for the survival of a species (Define habitat) • Less than 25% native prairie remains in Prairie Canada, or 20% in Saskatchewan.