Living Collection of FLORA GRAECA Sibthorpiana : FROM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acacia Saligna RA

Risk Assessment: ………….. ACACIA SALIGNA Prepared by: Etienne Branquart (1), Vanessa Lozano (2) and Giuseppe Brundu (2) (1) [[email protected]] (2) Department of Agriculture, University of Sassari, Italy [[email protected]] Date: first draft 01 st November 2017 Subsequently Reviewed by 2 independent external Peer Reviewers: Dr Rob Tanner, chosen for his expertise in Risk Assessments, and Dr Jean-Marc Dufor-Dror chosen for his expertise on Acacia saligna . Date: first revised version 04 th January 2018, revised in light of comments from independent expert Peer Reviewers. Approved by the IAS Scientific Forum on 26/10/2018 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Branquart, Lozano & Brundu PRA Acacia saligna 8 9 10 Contents 11 Summary of the Express Pest Risk Assessment for Acacia saligna 4 12 Stage 1. Initiation 6 13 1.1 - Reason for performing the Pest Risk Assessment (PRA) 6 14 1.2 - PRA area 6 15 1.3 - PRA scheme 6 16 Stage 2. Pest risk assessment 7 17 2.1 - Taxonomy and identification 7 18 2.1.1 - Taxonomy 7 19 2.1.2 - Main synonyms 8 20 2.1.3 - Common names 8 21 2.1.4 - Main related or look-alike species 8 22 2.1.5 - Terminology used in the present PRA for taxa names 9 23 2.1.6 - Identification (brief description) 9 24 2.2 - Pest overview 9 25 2.2.2 - Habitat and environmental requirements 10 26 2.2.3 Resource acquisition mechanisms 12 27 2.2.4 - Symptoms 12 28 2.2.5 - Existing PRAs 12 29 Socio-economic benefits 13 30 2.3 - Is the pest a vector? 14 31 2.4 - Is a vector needed for pest entry or spread? 15 32 2.5 - Regulatory status of the pest 15 33 2.6 - Distribution -

Well-Known Plants in Each Angiosperm Order

Well-known plants in each angiosperm order This list is generally from least evolved (most ancient) to most evolved (most modern). (I’m not sure if this applies for Eudicots; I’m listing them in the same order as APG II.) The first few plants are mostly primitive pond and aquarium plants. Next is Illicium (anise tree) from Austrobaileyales, then the magnoliids (Canellales thru Piperales), then monocots (Acorales through Zingiberales), and finally eudicots (Buxales through Dipsacales). The plants before the eudicots in this list are considered basal angiosperms. This list focuses only on angiosperms and does not look at earlier plants such as mosses, ferns, and conifers. Basal angiosperms – mostly aquatic plants Unplaced in order, placed in Amborellaceae family • Amborella trichopoda – one of the most ancient flowering plants Unplaced in order, placed in Nymphaeaceae family • Water lily • Cabomba (fanwort) • Brasenia (watershield) Ceratophyllales • Hornwort Austrobaileyales • Illicium (anise tree, star anise) Basal angiosperms - magnoliids Canellales • Drimys (winter's bark) • Tasmanian pepper Laurales • Bay laurel • Cinnamon • Avocado • Sassafras • Camphor tree • Calycanthus (sweetshrub, spicebush) • Lindera (spicebush, Benjamin bush) Magnoliales • Custard-apple • Pawpaw • guanábana (soursop) • Sugar-apple or sweetsop • Cherimoya • Magnolia • Tuliptree • Michelia • Nutmeg • Clove Piperales • Black pepper • Kava • Lizard’s tail • Aristolochia (birthwort, pipevine, Dutchman's pipe) • Asarum (wild ginger) Basal angiosperms - monocots Acorales -

Lamiales Newsletter

LAMIALES NEWSLETTER LAMIALES Issue number 4 February 1996 ISSN 1358-2305 EDITORIAL CONTENTS R.M. Harley & A. Paton Editorial 1 Herbarium, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, UK The Lavender Bag 1 Welcome to the fourth Lamiales Universitaria, Coyoacan 04510, Newsletter. As usual, we still Mexico D.F. Mexico. Tel: Lamiaceae research in require articles for inclusion in the +5256224448. Fax: +525616 22 17. Hungary 1 next edition. If you would like to e-mail: [email protected] receive this or future Newsletters and T.P. Ramamoorthy, 412 Heart- Alien Salvia in Ethiopia 3 and are not already on our mailing wood Dr., Austin, TX 78745, USA. list, or wish to contribute an article, They are anxious to hear from any- Pollination ecology of please do not hesitate to contact us. one willing to help organise the con- Labiatae in Mediterranean 4 The editors’ e-mail addresses are: ference or who have ideas for sym- [email protected] or posium content. Studies on the genus Thymus 6 [email protected]. As reported in the last Newsletter the This edition of the Newsletter and Relationships of Subfamily Instituto de Quimica (UNAM, Mexi- the third edition (October 1994) will Pogostemonoideae 8 co City) have agreed to sponsor the shortly be available on the world Controversies over the next Lamiales conference. Due to wide web (http://www.rbgkew.org. Satureja complex 10 the current economic conditions in uk/science/lamiales). Mexico and to allow potential partici- This also gives a summary of what Obituary - Silvia Botta pants to plan ahead, it has been the Lamiales are and some of their de Miconi 11 decided to delay the conference until uses, details of Lamiales research at November 1998. -

Medicinal, Nutritional and Industrial Applications of Salvia Species: a Revisit

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 43(2), March - April 2017; Article No. 06, Pages: 27-37 ISSN 0976 – 044X Review Article Medicinal, Nutritional and Industrial Applications of Salvia species: A Revisit Anita Yadav*1, Anuja Joshi1, S.L. Kothari2, Sumita Kachhwaha3, Smita Purohit1 1 The IIS University, 2Amity University Rajasthan, 3University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, India. *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] Received: 31-01-2017; Revised: 18-03-2017; Accepted: 05-04-2017. ABSTRACT Salvia species have been used for culinary, medicinal, nutritional and pharmacological purposes. In recent years, studies have highlighted the effect of Salvia plants in preventing and controlling various diseases naturally in a more safe manner. They have many biologically active compounds like essential oils and polyphenolics, which have been found to possess antimicrobial, anti- mutagenic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-cholinesterase properties. Currently, the demand for these plants and their derivatives has increased in food and pharmaceutical industries because they are recognized as safe products. This review summarizes the nutritional, medicinal and industrial applications of genus Salvia. Keywords: Salvia species, Essential oil, Polyphenolic compounds, Medicinal applications. INTRODUCTION flavonoids and phenolic acids3. Essential oils are mixture of several hundred constituents, which can be alvia, a member of the mint family ‘Lamiaceae’ categorized into monoterpene hydrocarbons, oxygenated comprises the largest genus -

Environmental Weeds of Coastal Plains and Heathy Forests Bioregions of Victoria Heading in Band

Advisory list of environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria Heading in band b Advisory list of environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria Heading in band Advisory list of environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria Contents Introduction 1 Purpose of the list 1 Limitations 1 Relationship to statutory lists 1 Composition of the list and assessment of taxa 2 Categories of environmental weeds 5 Arrangement of the list 5 Column 1: Botanical Name 5 Column 2: Common Name 5 Column 3: Ranking Score 5 Column 4: Listed in the CALP Act 1994 5 Column 5: Victorian Alert Weed 5 Column 6: National Alert Weed 5 Column 7: Weed of National Significance 5 Statistics 5 Further information & feedback 6 Your involvement 6 Links 6 Weed identification texts 6 Citation 6 Acknowledgments 6 Bibliography 6 Census reference 6 Appendix 1 Environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria listed alphabetically within risk categories. 7 Appendix 2 Environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria listed by botanical name. 19 Appendix 3 Environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria listed by common name. 31 Advisory list of environmental weeds of coastal plains and heathy forests bioregions of Victoria i Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment Melbourne, March2008 © The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2009 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. -

Biological Properties of Cistus Species

Biological properties of Cistus species. 127 © Wydawnictwo UR 2018 http://www.ejcem.ur.edu.pl/en/ ISSN 2544-1361 (online); ISSN 2544-2406 European Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine doi: 10.15584/ejcem.2018.2.8 Eur J Clin Exp Med 2018; 16 (2): 127–132 REVIEW PAPER Agnieszka Stępień 1(ABDGF), David Aebisher 2(BDGF), Dorota Bartusik-Aebisher 3(BDGF) Biological properties of Cistus species 1 Centre for Innovative Research in Medical and Natural Sciences, Laboratory of Innovative Research in Dietetics Faculty of Medicine, University of Rzeszow, Rzeszów, Poland 2 Department of Human Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rzeszów, Poland 3 Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rzeszów, Poland ABSTRACT Aim. This paper presents a review of scientific studies analyzing the biological properties of different species of Cistus sp. Materials and methods. Forty papers that discuss the current research of Cistus sp. as phytotherapeutic agent were used for this discussion. Literature analysis. The results of scientific research indicate that extracts from various species of Cistus sp. exhibit antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, cytotoxic and anticancer properties. These properties give rise to the pos- sibility of using Cistus sp. as a therapeutic agent supporting many therapies. Keywords. biological properties, Cistus sp., medicinal plants Introduction cal activity which elicit healing properties. Phytochem- Cistus species (family Cistaceacea) are perennial, dicot- ical studies using chromatographic and spectroscopic yledonous flowering shrubs in white or pink depend- techniques have shown that Cistus is a source of active ing on the species. Naturally growing in Europe mainly bioactive compounds, mainly phenylpropanoids (flavo- in the Mediterranean region and in western Africa and noids, polyphenols) and terpenoids. -

Plant List for Web Page

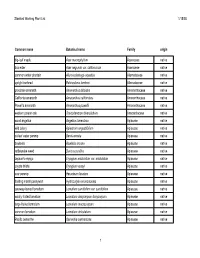

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Environmental Control of Terpene Emissions from Cistus Monspeliensis L

Environmental control of terpene emissions from Cistus monspeliensis L. in natural Mediterranean shrublands A. Rivoal, C. Fernandez, A.V. Lavoir, R. Olivier, C. Lecareux, Stephane Greff, P. Roche, B. Vila To cite this version: A. Rivoal, C. Fernandez, A.V. Lavoir, R. Olivier, C. Lecareux, et al.. Environmental control of terpene emissions from Cistus monspeliensis L. in natural Mediterranean shrublands. Chemosphere, Elsevier, 2010, 78 (8), p. 942 - p. 949. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.047. hal-00519783 HAL Id: hal-00519783 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00519783 Submitted on 21 Sep 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rivoal A., Fernandez C., Lavoir A.V., Olivier R., Lecareux C., Greff S., Roche P. and Vila B. (2010) Environmental control of terpene emissions from Cistus monspeliensis L. in natural Mediterranean shrublands, Chemosphere, 78, 8, 942-949. Author-produced version of the final draft post-refeering the original publication is available at www.elsevier.com/locate/chemosphere DOI: 0.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.12.047 Environmental -

The Evolution of Pollinator–Plant Interaction Types in the Araceae

BRIEF COMMUNICATION doi:10.1111/evo.12318 THE EVOLUTION OF POLLINATOR–PLANT INTERACTION TYPES IN THE ARACEAE Marion Chartier,1,2 Marc Gibernau,3 and Susanne S. Renner4 1Department of Structural and Functional Botany, University of Vienna, 1030 Vienna, Austria 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Centre National de Recherche Scientifique, Ecologie des Foretsˆ de Guyane, 97379 Kourou, France 4Department of Biology, University of Munich, 80638 Munich, Germany Received August 6, 2013 Accepted November 17, 2013 Most plant–pollinator interactions are mutualistic, involving rewards provided by flowers or inflorescences to pollinators. An- tagonistic plant–pollinator interactions, in which flowers offer no rewards, are rare and concentrated in a few families including Araceae. In the latter, they involve trapping of pollinators, which are released loaded with pollen but unrewarded. To understand the evolution of such systems, we compiled data on the pollinators and types of interactions, and coded 21 characters, including interaction type, pollinator order, and 19 floral traits. A phylogenetic framework comes from a matrix of plastid and new nuclear DNA sequences for 135 species from 119 genera (5342 nucleotides). The ancestral pollination interaction in Araceae was recon- structed as probably rewarding albeit with low confidence because information is available for only 56 of the 120–130 genera. Bayesian stochastic trait mapping showed that spadix zonation, presence of an appendix, and flower sexuality were correlated with pollination interaction type. In the Araceae, having unisexual flowers appears to have provided the morphological precon- dition for the evolution of traps. Compared with the frequency of shifts between deceptive and rewarding pollination systems in orchids, our results indicate less lability in the Araceae, probably because of morphologically and sexually more specialized inflorescences. -

Colonial Garden Plants

COLONIAL GARD~J~ PLANTS I Flowers Before 1700 The following plants are listed according to the names most commonly used during the colonial period. The botanical name follows for accurate identification. The common name was listed first because many of the people using these lists will have access to or be familiar with that name rather than the botanical name. The botanical names are according to Bailey’s Hortus Second and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (3, 4). They are not the botanical names used during the colonial period for many of them have changed drastically. We have been very cautious concerning the interpretation of names to see that accuracy is maintained. By using several references spanning almost two hundred years (1, 3, 32, 35) we were able to interpret accurately the names of certain plants. For example, in the earliest works (32, 35), Lark’s Heel is used for Larkspur, also Delphinium. Then in later works the name Larkspur appears with the former in parenthesis. Similarly, the name "Emanies" appears frequently in the earliest books. Finally, one of them (35) lists the name Anemones as a synonym. Some of the names are amusing: "Issop" for Hyssop, "Pum- pions" for Pumpkins, "Mushmillions" for Muskmellons, "Isquou- terquashes" for Squashes, "Cowslips" for Primroses, "Daffadown dillies" for Daffodils. Other names are confusing. Bachelors Button was the name used for Gomphrena globosa, not for Centaurea cyanis as we use it today. Similarly, in the earliest literature, "Marygold" was used for Calendula. Later we begin to see "Pot Marygold" and "Calen- dula" for Calendula, and "Marygold" is reserved for Marigolds. -

Microsculpture of Cypsela Surface of Bellis L. (Asteraceae) in Libya Ghalia T

Research Article ISSN: 0976-7126 CODEN (USA): IJPLCP Rabiai & Elbadry , 12(2):1-5, 2021 [[ Microsculpture of cypsela surface of Bellis L. (Asteraceae) in Libya Ghalia T. El Rabiai* and Seham H. Elbadry Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Benghazi University, Libya Abstract Article info In this study, the cypsela surfaces of three taxa belonging to the genus Bellis L. were investigated in details by means of electron microscopy. Received: 12/01/2021 The main aim of this study was to characterize the microsculpture of cypsela surface of the Libyan taxa of Bellis. (Asteraceae). Detailed Revised: 28/01/2021 descriptions of cypsela surface were given for each taxon. The results indicated that the examined taxa had very high variations regarding their Accepted: 27/02/2021 cypselae surfaces and these variations have great importance in determining the taxonomic relationships of the discussed taxa. Based on © IJPLS the results, pericarp texture and color could be used for taxonomical diagnosis. The fruit coat was usually roguish and its ornamentation was www.ijplsjournal.com fairly variable; therefore, this taxonomical microcharacter might also be useful in distinguishing closely related taxa. The hairiness of the surface of the pericarp was characteristic in the studied taxa. Key words: Bellis , Asteraceae, fruit surface, micromorphology, Libya [ Introduction The Asteraceae is a large family belonging to were observed among the taxa. Cypselae Asterales (Sennikov et al ., 2016) and is about were dry, indehiscent, unilocular, with a 10% of all angiosperms, comprises 1700 single seed that is usually not adnate to the genera and about 27000 accepted species pericarp (linked only by the funicle) and (Moreira et al . -

Climate Change Reduces Nectar Secretion in Two Common Mediterranean Plants

Research Article Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aobpla/article-abstract/doi/10.1093/aobpla/plv111/1803994 by guest on 25 October 2018 Climate change reduces nectar secretion in two common Mediterranean plants Krista Takkis*, Thomas Tscheulin, Panagiotis Tsalkatis and Theodora Petanidou Laboratory of Biogeography and Ecology, Department of Geography, University of the Aegean, University Hill, GR-81100 Mytilene, Greece Received: 21 May 2015; Accepted: 31 August 2015; Published: 15 September 2015 Associate Editor: Colin M. Orians Citation: Takkis K, Tscheulin T, Tsalkatis P, Petanidou T. 2015. Climate change reduces nectar secretion in two common Mediterranean plants. AoB PLANTS 7: plv111; doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv111 Abstract. Global warming can lead to considerable impacts on natural plant communities, potentially inducing changes in plant physiology and the quantity and quality of floral rewards, especially nectar. Changes in nectar pro- duction can in turn strongly affect plant–pollinator interaction networks—pollinators may potentially benefit under moderate warming conditions, but suffer as resources reduce in availability as elevated temperatures become more extreme. Here, we studied the effect of elevated temperatures on nectar secretion of two Mediterranean Lamiaceae species—Ballota acetabulosa and Teucrium divaricatum. We measured nectar production (viz. volume per flower, sugar concentration per flower and sugar content per flower and per plant), number of open and empty flowers per plant, as well as biomass per flower under a range of temperatures selected ad hoc in a fully controlled climate chamber and under natural conditions outdoors. The average temperature in the climate chamber was increased every 3 days in 3 8C increments from 17.5 to 38.5 8C.