Boundless: Conservation and Development on the Southern African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCT World Youth Rhino Summit Information Booklet 9 July

In September 2014, the world will hear the voices of the youth speaking out against rhino poaching and the decimation of other endangered species at the inaugural ! WORLD YOUTH RHINO SUMMIT 21-23 September 2014 (incorporating World Rhino Day) ! Centenary Centre, iMfolozi Game Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa ! ! ! Contact: Email: [email protected] Website: www.youthrhinosummit.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/YouthRhinoSummit ! Twitter: www.twitter.com/WYRhinoSummit SCT/FINAL/10/7/14 ! Wildlife crime is the fourth About the World Youth Rhino Summit most profitable illegal trade in Wildlife crime has exploded in recent years to meet the increasing demand for the world after drugs, arms rhino horn, elephant ivory and tiger products, particularly in Asia. The rhino and human trafficking, poaching crisis affecting South Africa and other African and Asian rhino range estimated at US$19 billion states is now recognised as a worldwide wildlife emergency. The brutal killing of rhinos - particularly in South Africa - is being driven by global criminal syndicates, many with links to international terrorism and narcotics cartels. Equally as important as fighting the front-line battles, improving anti-poaching operations and global law enforcement efforts to counter wildlife crime, is the need for a critical mass of support that will drive informed global awareness of the value of rhinos, not just economically but also their value to Africa’s and Asia’s heritage and biodiversity in the decades to come. This is taking shape and significantly: tens of thousands of young people !in South Africa, other African states and internationally are calling for rhino poaching to be stopped. -

Publication No. 201619 Notice No. 48 B

CIPC PUBLICATION 16 December 2016 Publication No. 201619 Notice No. 48 B (AR DEREGISTRATIONS – Non Profit Companies) COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS CIPC PUBLICATION NOTICE 19 OF 2016 COMPANIES AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY COMMISSION NOTICE IN TERMS OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 (ACT 71 OF 2008) THE FOLLOWING NOTICE RELATING TO THE DEREGISTRATION OF ENTITIES IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT ARE PUBLISHED FOR GENERAL INFORMATION. THE CIPC WEBSITE AT WWW.CIPC.CO.ZA CAN BE VISITED FOR MORE INFORMATION. NO GUARANTEE IS GIVEN IN RESPECT OF THE ACCURACY OF THE PARTICULARS FURNISHED AND NO RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR ERRORS AND OMISSIONS OR THE CONSEQUENCES THEREOF. Adv. Rory Voller COMMISSIONER: CIPC NOTICE 19 OF 2016 NOTICE IN TERMS OF SECTION 82 OF THE COMPANIES ACT, 2008 RELATING TO ANNUAL RETURN DEREGISTRATIONS OF COMPANIES AND CLOSE CORPORATIONS K2011100425 SOWETO CITY INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCY K2011100458 K2011100458 K2011105301 VOICE OF SOLUTION GOSPEL CHURCH K2011105344 BOYES HELPING HANDS K2011105653 RACE 4 CHARITY K2011105678 OYISA FOUNDATION K2011101248 ONE FUTURE DEVELOPMENT 53 K2011101288 EXTRA TIME FOOTBALL SKILLS DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION K2011108390 HALCYVISION K2011112257 YERUSHALYIM CHRISTIAN CHURCH K2011112598 HOLINERS CHURCH OF CHRIST K2011106676 AMSTIZONE K2011101559 MOLEPO LONG DISTANCE TAXI ASSOCIATION K2011103327 CASHAN X25 HUISEIENAARSVERENIGING K2011118128 JESUS CHRIST HEALS MINISTRY K2011104065 ZWELIHLE MICRO FINANCE COMPANY K2011111623 COVENANT HOUSE MIRACLE CENTRE K2011119146 TSHIAWELO PATRONS COMMUNITY -

Ecological Suitability Modeling for Anthrax in the Kruger National Park, South Africa

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ecological suitability modeling for anthrax in the Kruger National Park, South Africa Pieter Johan Steenkamp1, Henriette van Heerden2*, Ockert Louis van Schalkwyk2¤ 1 University of Pretoria, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Department of Production Animal Studies, Onderstepoort, South Africa, 2 University of Pretoria, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Onderstepoort, South Africa ¤ Current address: Office of the State Veterinarian, Skukuza, South Africa * [email protected] Abstract a1111111111 The spores of the soil-borne bacterium, Bacillus anthracis, which causes anthrax are highly a1111111111 resistant to adverse environmental conditions. Under ideal conditions, anthrax spores can a1111111111 a1111111111 survive for many years in the soil. Anthrax is known to be endemic in the northern part of a1111111111 Kruger National Park (KNP) in South Africa (SA), with occasional epidemics spreading southward. The aim of this study was to identify and map areas that are ecologically suitable for the harboring of B. anthracis spores within the KNP. Anthrax surveillance data and selected environmental variables were used as inputs to the maximum entropy (Maxent) OPEN ACCESS species distribution modeling method. Anthrax positive carcasses from 1988±2011 in KNP (n = 597) and a total of 40 environmental variables were used to predict and evaluate their Citation: Steenkamp PJ, van Heerden H, van Schalkwyk OL (2018) Ecological suitability relative contribution to suitability for anthrax occurrence in KNP. The environmental vari- modeling for anthrax in the Kruger National Park, ables that contributed the most to the occurrence of anthrax were soil type, normalized dif- South Africa. PLoS ONE 13(1): e0191704. https:// ference vegetation index (NDVI) and precipitation. -

SANDF Control of the Northern and Eastern Border Areas of South Africa Ettienne Hennop, Arms Management Programme, Institute for Security Studies

SANDF Control of the Northern and Eastern Border Areas of South Africa Ettienne Hennop, Arms Management Programme, Institute for Security Studies Occasional Paper No 52 - August 2001 INTRODUCTION Borderline control and security were historically the responsibility of the South African Police (SAP) until the withdrawal of the counterinsurgency units at the end of 1990. The Army has maintained a presence on the borders in significant numbers since the 1970s. In the Interim Constitution of 1993, borderline functions were again allocated to the South African Police Service (SAPS). However, with the sharp rise in crime in the country and the subsequent extra burden this placed on the police, the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) was placed in service by the president to assist and support the SAPS with crime prevention, including assistance in borderline security. As a result, the SANDF had a strong presence with 28 infantry companies and five aircraft deployed on the international borders of South Africa at the time.1 An agreement was signed on 10 June 1998 between the SANDF and the SAPS that designated the responsibility for borderline protection to the SANDF. In terms of this agreement, as contained in a cabinet memorandum, the SANDF has formally been requested to patrol the borders of South Africa. This is to ensure that the integrity of borders is maintained by preventing the unfettered movement of people and goods across the South African borderline between border posts. The role of the SANDF has been defined technically as one of support to the SAPS and other departments to combat crime as requested.2 In practice, however, the SANDF patrols without the direct support of the other departments. -

Rhino Poaching

250,000 children say ‘NO!’ to rhino poaching The Rhino Art campaign remains the most comprehensive children’s rhino conservation education programme ever undertaken. Its clear objective is to gather the largest number of children’s hearts-and-minds messages as a call to action against rhino poaching and all forms of wildlife crime. The rallying cry is “Siyabathanda oBhejane – Siyabathanda! We love and care for our rhino: Let Our Voices Be Heard!” BACKGROUND Project Rhino KZN and the Kingsley Holgate Foundation joined forces in April 2013 for the Izintaba Zobombo Expedition, which traversed the Lubombo Mountain Range that forms South Africa’s border with Mozambique, from Zimbabwe in the north to the Indian Ocean. This region is home to the largest concentration of wild rhinos in the world. The expedition travelled through the Kruger National Park and nearby private reserves, across the fence line into the ‘Rhino War Zone’ of Mozambique and Parc Nacional do Limpopo, and south through the nature reserves of Swaziland and northern KwaZulu-Natal. And so began the most comprehensive youth-orientated survey on rhino poaching ever carried out in Southern Africa. Using art and soccer, the Rhino Art-Let Our Children’s Voices Be Heard campaign has now reached over 250,000 young people mainly throughout southern and central Africa with a rhino conservation message that encourages them to voice their thoughts about rhino poaching. It involves local communities that are at times silent witnesses to the rhino poaching war, increases conservation awareness amongst the youth and adds to the groundswell of public support needed to end rhino poaching and other wildlife crimes. -

River Flow and Quality

Setting the Thresholds of Potential Concern for River Flow and Quality Rationale All of the seven major rivers which flow in an easterly direction through the Kruger National Park (KNP) originate in the higher lying areas west of the KNP where they are highly utilised (Du Toit, Rogers and Biggs 2003). The KNP lies in a relatively arid (490 mm KNP average rainfall) area and thus the rivers are a crucially important component for the conservation of biodiversity in the KNP (Du Toit, Rogers and Biggs 2003). Population growth in the eastern Lowveld of South Africa during the past three decades has brought with it numerous environmental challenges. These include, but are not limited to, extensive planting of exotic plantations, overgrazing, erosion, over-utilisation and pollution of rivers, as well as clearing of indigenous forests from large areas in the upper catchments outside the borders of the KNP. The degradation of each river varies in character, intensity and causes with a substantial impact on downstream users. The successful management of these rivers poses one of the most serious challenges to the KNP. However, over the past 10 years South Africa has revolutionised its water legislation (National Water Act, Act number 36 of 1998). This Act substantially elevated the status of the environmental needs, through defining the ecological reserve as a priority water requirement. In other words this entails water of sufficient flow and quality to maintain the integrity of the ecological system, including the water therein, for human use. With the current levels of abstraction in the upper catchments, the KNP quite simply does not receive the water quantity and quality required to maintain the in-stream biota. -

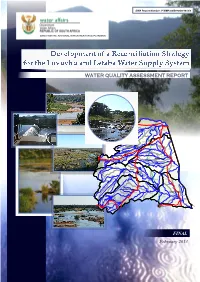

Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT

DWA Report Number: P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 DIRECTORATE: NATIONAL WATER RESOURCE PLANNING Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT u Luvuvh A91K A92C A91J le ta Mu A92B A91H B90A hu uv v u A92A Luvuvhu / Mutale L Fundudzi Mphongolo B90E A91G B90B Vondo Thohoyandou Nandoni A91E A91F B90C B90D A91A A91D Shingwedzi Makhado Shing Albasini Luv we uv dz A91C hu i Kruger B90F B90G A91B KleinLeta B90H ba B82F Nsami National Klein Letaba B82H Middle Letaba Giyani B82E Klein L B82G e Park B82D ta ba B82J B83B Lornadawn B81G a B81H b ta e L le d id B82C M B83C B82B B82A Groot Letaba etaba ot L Gro B81F Lower Letaba B81J Letaba B83D B83A Tzaneen B81E Magoebaskloof Tzaneen a B81B B81C Groot Letab B81A B83E Ebenezer Phalaborwa B81D FINAL February 2013 DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT REFERENCE This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Department of Water Affairs, South Africa, 2012. DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM: WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT Prepared by: Golder Associates Africa Report No. P WMA 02/B810/00/1412/8 Water Quality Assessment Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for the Luvuvhu and Letaba Water Supply System Report DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR THE LUVUVHU AND LETABA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM Water Quality Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Department of Water Affairs (DWA) has identified the need for the Reconciliation Study for the Luvuvhu-Letaba WMA. -

Paper Sessions 41St National AAZK Conference Orlando, FL

Pro]__^ings of th_ 41st N[tion[l Conf_r_n]_ of th_ @m_ri][n @sso]i[tion of Zoo K__p_rs, In]. "KEEPERS MAKING A WORLD OF DIFFERENCE" Paper Sessions 41st National AAZK Conference Orlando, FL September 8-12, 2014 Welcome to the 41st American Association of Zoo Keepers National Conference “Keepers Making a World of Difference” Hosted by the Greater Orlando AAZK Chapter & Disney’s Animal Kingdom Our Chapter is thrilled by this opportunity to welcome you to our world! The members have been working hard to ensure that the 2014 AAZK Conference will be an experience you will always remember. This year’s conference will allow you to enjoy the Walt Disney World Resort, while connecting and developing profes- sionally with your colleagues from animal institutions around the globe. In partnership with your national AAZK Professional Development Committee, we are excited to bring you a varied program of workshops, papers, and speakers as the foundation of your conference experience. Addi- tionally, the AAZK, Inc. Specialized Training Workshop Series will debut “The Core Elements of Zoo Keeping” and an in-depth Hospital/Quarantine workshop. These featured programs are a track of AAZK’s Certification Series, brought to you in collaboration with AAZK Online Learning. Highlights of this year’s conference will include an Epcot icebreaker in The Seas with Nemo and Friends pavil- ion, followed by a dessert party with an exclusive viewing area for the nighttime spectacular, “Illuminations: Reflections of Earth.” We are also pleased to present a distinctive zoo day, which will take you “behind the magic” at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. -

Kruger National Park River Research: a History of Conservation and the ‘Reserve’ Legislation in South Africa (1988-2000)

Kruger National Park river research: A history of conservation and the ‘reserve’ legislation in South Africa (1988-2000) L. van Vuuren 23348674 Dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in History at the School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof J.W.N. Tempelhoff May 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Masters of Arts in the subject group History, School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle Faculty, North-West University. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination in any other university. L. van Vuuren May 2017 i ABSTRACT Like arteries in a human body, rivers not only transport water and life-giving nutrients to the landscape they feed, they are also shaped and characterised by the catchments which they drain.1 The river habitat and resultant biodiversity is a result of several physical (or abiotic) processes, of which flow is considered the most important. Flows of various quantities and quality are required to flush away sediments, transport nutrients, and kick- start life processes in the freshwater ecosystem. South Africa’s river systems are characterised by particularly variable flow regimes – a result of the country’s fluctuating climate regime, which varies considerably between wet and dry seasons. When these flows are disrupted or diminished through, for example, direct water abstraction or the construction of a weir or dam, it can have severe consequences on the ecological process which depend on these flows. -

RDUCROT Baseline Report Limpopo Mozambique

LAND AND WATER GOVERNANCE AND PROPOOR MECHANISMS IN THE MOZAMBICAN PART OF THE LIMPOPO BASIN: BASELINE STUDY WORKING DOCUMENT DECEMBER 2011 Raphaëlle Ducrot Project : CPWF Limpopo Basin : Water Gouvernance 1 SOMMAIRE 1 THE FORMAL INSTITUTIONAL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK 6 1.1 Territorial and administrative governance 6 1.1.1 Provincial level 6 1.1.2 District level 7 1.1.3 The Limpopo National Park 9 1.2 Land management 11 1.3 Traditional authorities 13 1.4 Water Governance framework 15 1.4.1 International Water Governance 15 1.4.2 Governance of Water Resources 17 a) Water management at national level 17 b) Local and decentralized water institutions 19 ARA 19 The Limpopo Basin Committee 20 Irrigated schemes 22 Water Users Association in Chokwé perimeter (WUA) 24 1.4.3 Governance of domestic water supply 25 a) Cities and peri-urban areas (Butterworth and O’Leary, 2009) 25 b) Rural areas 26 1.4.4 Local water institutions 28 1.4.5 Governance of risks and climate change 28 1.5 Official aid assistance and water 29 1.6 Coordination mechanisms 30 c) Planning and budgeting mechanisms in the water sector (Uandela, 2010) 30 d) Between government administration 31 e) Between donor and government 31 f) What coordination at decentralized level? 31 2 THE HYDROLOGICAL FUNCTIONING OF THE MOZAMBICAN PART OF THE LIMPOPO BASIN 33 2.1 Description of the basin 33 2.2 Water availability 34 2.2.1 Current uses (Van der Zaag, 2010) 34 2.2.2 Water availability 35 2.3 Water related risks in the basin 36 2.4 Other problems 36 2 3 WATER AND LIVELIHOODS IN THE LIMPOPO BASIN 37 3.1 a short historical review 37 3.2 Some relevant social and cultural aspects 40 3.3 Livelihoods in Limpopo basin 42 3.4 Gender aspects 45 3.5 Vulnerability to risks and resilience 46 3.5.1 Water hazards: one among many stressors. -

9588 Autolive 84.Indd

15 000 SUBSCRIBERS www.autolive.co.za Issue No. 84 | 29 April 2016 MOTOR INDUSTRY EXPORTS EXCEL Dr. Norman Lamprecht, Executive Manager of the South Africa National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of Automotive SA (NAAMSA) as well as Director of the Automotive Industry Export Council (AIEC) has provided AutoLive with a special preview of the information contained Export in his annual Automotive Export Manual publication, which he produces on behalf of the AIEC. Manual Th e Automotive Export Manual – 2016 – South Africa is an annual publication produced and compiled by the Automotive Industry Export Council (AIEC) – the recognised source of South African automotive trade data. Th e 2016 publication, as well as the previous nine publications since 2007, provides a comprehensive guide on the export and import performance of the South African automotive industry under the previ- 2016 ous Motor Industry Development Programme (MIDP) and current Automotive Production Development Programme (APDP). Th e aim of the manual is to identify and report on the major automotive export destinations, the major countries of origin, the main automotive export trade blocs, the most important automotive products being exported and imported, the top growth markets and products as well as the impact of the trade arrangements enjoyed by South Africa on automotive trade patterns. For 2015, total automotive industry exports in- creased by R35,8 billion or 30,9% to R151,5 billion from the R115,7 billion in 2014 and comprised a signifi cant 14,6% of South Africa’s total export earnings. Th is is the second time that the industry exceeded the R100 billion export level. -

Shingwedzi 20

N CARAVAN & OUTDOOR LIFE CARAVAN N ov EMBE R 2010 ove mb ER WIN: 2010 Sh 2x two-week holidays in KZN! IN gw ED z I • C A mp & Shingwedzi SCU b A 4x4 Eco-Trail • 13 BUSH CAMPING IN MOZ TENTS TENT TIP-OFF models • 20 g to choose from LA 20 13 m OROUS GLAMOROUS GADGETS g German engineering AD meets caravan style g ETS D Thaba Monaté E WWW.CARAVANSA.CO.ZA W Lake Eland Game Reserve E DIVE RIGHT IN! VI Fish River Diner Caravan Park E RESORTS Camp & SCUBA R San Cha Len R26.80 (incl. VAT) BUSH FEAST: bRAAIED ChICkEN & SLAp ChIpS OUTSIDE SA R23.50 VAT excl. DON'T GET SCAMMED! RISky INTERNET pURChASES 2010 TOP PRINT PERFORMER ON THE WAR Photos by Mark Samuel and Grant Spolander PATH Words by Mark Samuel Words 20 Caravan & Outdoor Life • November 2010 SHINGWEDZI ECO-TRAIL Adjacent to Kruger, across the Mozambique border, lies Parque Nacional do Limpopo – the Mozambique portion of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. The fences between the parks are slowly coming down, and the popularity of this destination is increasing steadily. The best way to experience the region is on the Shingwedzi 4x4 Eco-Trail. So, with a Conqueror hitched to our Toyota Hilux, we set off to see what this trail has to offer. The briefing before the trail commences lets you know exactly where you’re headed. here they were: ghostly grey South Africa’s Kruger National Park and time. It’s beautiful, untamed and wild – all behemoths moving stealthily Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park.