FRANS HALS (Antwerp 1582/3 – 1666 Haarlem)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print He Made After the Latter Work, All Date to 1638

Fighting Card Players and Death ca. 1638 oil on canvas Jan Lievens 67 x 84.9 cm (Leiden 1607 – 1674 Amsterdam) Signed and dated lower right: J. Lievens JL-107 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Fighting Card Players and Death Page 2 of 7 How to cite Wheelock, Arthur K., Jr. “Fighting Card Players and Death” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/fighting-card-players-and-death/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Fighting Card Players and Death Page 3 of 7 In 1635 Jan Lievens moved from London to Antwerp, perhaps expecting that Comparative Figures the arrival of the new governor-general of the Southern Netherlands, the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand, would usher in a period of peace and prosperity beneficial to the arts.[1] Lievens soon joined the local painters’ guild and settled into a community of artists who specialized in low-life genre scenes, landscapes, and still lifes, among them Adriaen Brouwer (1605/6–38), Jan Davide de Heem (1606–83/84), David Teniers the Younger (1610–90), and Jan Cossiers (1600–71). In 1635, Brouwer depicted these artists in a tavern scene, Smokers, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig 1).[2] The most inspirational of them for Lievens was Brouwer, who apparently encouraged Lievens to depict, once again, rough peasant types comparable to those he Fig 1. -

Plekken Van Plezier

Plekken van plezier Open Monumentendagen 14 & 15 september Haarlem - 1 Welkom in Haarlem Op de voorkant van dit programmaboekje prijkt zwembad De Houtvaart. Een prachtige plek van plezier in onze monumentenstad Haarlem. Dit jaar staat dan ook de amusementswaarde van monumenten centraal tijdens Open Monumentendagen, met als thema ‘Plekken van plezier’. Naar welke monumentale plekken gingen en gaan mensen voor hun plezier? Ik vind het belangrijk dat onze monumenten bewaard en beschermd blijven. Dat ze bezocht en bewonderd kunnen worden en dat ze ons leren wie we zijn en waar we vandaan komen. Veel vrijwilligers werken actief mee aan de organisatie en uitvoering van de Open Monumentendagen; vanaf deze plek wil ik iedereen hartelijk bedanken voor hun inzet. In dit boekje vindt u informatie over bijzondere monumenten in Haarlem die hun deuren voor u openen. Een mooie selectie van monumenten voor ontspanning, vermaak en vrije tijd. Ik wens u een plezierig weekend vol verrassende ervaringen toe! Floor Roduner, wethouder Monumenten en Erfgoed - 2 Plekken van plezier Hoe hebben mensen zich in de loop der eeuwen vermaakt en welke monumenten zijn daarvoor het decor of het podium geweest? Deze vragen zijn leidend geweest bij het samenstellen van dit programma boekje. In Haarlem zijn volop historische ‘plekken van plezier’ te vinden zoals theaters, musea, parken, markten en sportclubs. Al in de middeleeuwen zijn er plekken in Haarlem aan te wijzen die centraal staan voor vermaak. Zo had Haarlem als eerste stad ter wereld een heus sportveld, de ‘Baen’. Hier werden vanaf de 14de eeuw Oudhollandse spellen gespeeld. Een andere bekende plek van plezier is de Haarlemmerhout, een immense groene oase aan de zuidkant van de stad. -

Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst Cornelis De Bie, Het Gulden Cabinet Van De Edel Vry Schilderconst 244

Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst Cornelis de Bie bron Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst. Jan Meyssens, Juliaen van Montfort, Antwerpen 1662 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/bie_001guld01_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl 1 Het gulden cabinet vande edele vry schilder-const Ontsloten door den lanck ghevvenschten Vrede tusschen de twee mach- tighe Croonen van SPAIGNIEN EN VRANCRYCK, Waer-inne begrepen is den ontsterffe- lijcken loff vande vermaerste Constminnende Geesten ENDE SCHILDERS Van dese Eeuvv, hier inne meest naer het leven af-gebeldt, verciert met veel ver- makelijcke Rijmen ende Spreucken. DOOR Cornelis de Bie Notaris binnen Lyer. Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst 3 Den geboeyden Mars spreckt op d'uytleggingh van de titel plaet. WEl wijckt dan mijne Macht, en Raserny ter sijden? Moet mijne wreetheyt nu dees boose schant-vleck lijden? Dat ick hier ligh gheboyt en plat ter aert ghedruckt, Ontrooft van Sweert en Schilt, t'gen' my is af-geruckt? Alleen door liefdens kracht, die Vranckrijck heeft ontsteken, Die door het Echts verbont compt al mijn lusten breken, Die selffs de wreetheyt ben, wordt hier van liefd' gheplaegt, Den dullen Orloghs Godt wordt van den Peys verjaeght. Ach! d' Edel Fransche Trouw: (aen Spaenien verbonden:) Die heeft m' allendigh Helt in ballinckschap ghesonden. K' en heb niet eenen vriendt, men danckt my spoedigh aff Een jeder my verstoot, ick sien ick moet in't graff. Nochtans sal menich mensch mijn ongeluck beclaghen Die was ghewoon door my heel Belgica te plaeghen, Die was ghewoon met my te liggen op het landt Dat ick had uyt gheput door mijnen Orloghs brandt, De deught had ick verjaeght, en liefdens kracht ghenomen Midts dat mijn fury was in Neder-landt ghecomen Tot voordeel vanden Frans, die my nu brenght in druck En wederleyt mijn jonst, fortuyn en groot gheluck. -

Sztuki Piękne)

Sebastian Borowicz Rozdział VII W stronę realizmu – wiek XVII (sztuki piękne) „Nikt bardziej nie upodabnia się do szaleńca niż pijany”1079. „Mistrzami malarstwa są ci, którzy najbardziej zbliżają się do życia”1080. Wizualna sekcja starości Wiek XVII to czas rozkwitu nowej, realistycznej sztuki, opartej już nie tyle na perspektywie albertiańskiej, ile kepleriańskiej1081; to również okres malarskiej „sekcji” starości. Nigdy wcześniej i nigdy później w historii europejskiego malarstwa, wyobrażenia starych kobiet nie były tak liczne i tak różnicowane: od portretu realistycznego1082 1079 „NIL. SIMILIVS. INSANO. QVAM. EBRIVS” – inskrypcja umieszczona na kartuszu, w górnej części obrazu Jacoba Jordaensa Król pije, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 1080 Gerbrand Bredero (1585–1618), poeta niderlandzki. Cyt. za: W. Łysiak, Malarstwo białego człowieka, t. 4, Warszawa 2010, s. 353 (tłum. nieco zmienione). 1081 S. Alpers, The Art of Describing – Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago 1993; J. Friday, Photography and the Representation of Vision, „The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” 59:4 (2001), s. 351–362. 1082 Np. barokowy portret trumienny. Zob. także: Rembrandt, Modląca się staruszka lub Matka malarza (1630), Residenzgalerie, Salzburg; Abraham Bloemaert, Głowa starej kobiety (1632), kolekcja prywatna; Michiel Sweerts, Głowa starej kobiety (1654), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Monogramista IS, Stara kobieta (1651), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wiedeń. 314 Sebastian Borowicz po wyobrażenia alegoryczne1083, postacie biblijne1084, mitologiczne1085 czy sceny rodzajowe1086; od obrazów o charakterze historycznodokumentacyjnym po wyobrażenia należące do sfery historii idei1087, wpisujące się zarówno w pozy tywne1088, jak i negatywne klisze kulturowe; począwszy od Prorokini Anny Rembrandta, przez portrety ubogich staruszek1089, nobliwe portrety zamoż nych, starych kobiet1090, obrazy kobiet zanurzonych w lekturze filozoficznej1091 1083 Bernardo Strozzi, Stara kobieta przed lustrem lub Stara zalotnica (1615), Музей изобразительных искусств им. -

Title Connection Between Rough Brushstrokes and Vulgar Subjects in Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Paintings Author(S) Fukaya

Connection between Rough Brushstrokes and Vulgar Subjects Title in Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Paintings Author(s) Fukaya, Michiko Citation Kyoto Studies in Art History (2017), 2: 55-71 Issue Date 2017-04 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/229460 © Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University and the Right authors Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 55 Connection between Rough Brushstrokes and Vulgar Subjects in Seventeenth-Century Netherlandish Paintings Michiko Fukaya 1. Introduction Karel van Mander stated in his Schilder-boeck that painters at the time were accustomed to applying their paint more thickly than before; hence, their paintings were made seemingly of stone relief.1 At the same time, he used the terms “uneven and rough (oneffen en rouw)” and “beautifully, neat and clear (schoon, net en blijde)” as two contrasting manners in the application of paint.2 His comment is followed by a well-known passage referring to Titian’s earlier style, executed “with incredible neatness (met onghelooflijcke netticheyt)” and his later one, “with stains and rough strokes (met vlecken en rouw’ streken)”. In 1604, when van Mander was writing the above passage, it was uncommon among Netherlandish painters to paint so thickly that their paintings might be compared to a relief. Nevertheless, in Lives of the Northern Painters, van Mander mentioned two painters who applied their paint so thick that the canvas could not be rolled or had to be scraped off,3 although such rough manner was more tightly connected to the Italian style. In any event, the dichotomy of the neatness and the roughness of application of the paint was introduced into Netherlandish art theory at the time. -

The Dutch Golden Age: a New Aurea Ætas? the Revival of a Myth in the Seventeenth-Century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018

The Dutch Golden Age: a new aurea ætas? The revival of a myth in the seventeenth-century Republic Geneva, 31 May – 2 June 2018 « ’T was in dien tyd de Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst, en de goude appelen (nu door akelige wegen en zweet naauw te vinden) dropen den Konstenaars van zelf in den mond » (‘This time was the Golden Age for Art, and the golden apples (now hardly to be found if by difficult roads and sweat) fell spontaneously in the mouths of Artists.’) Arnold Houbraken, De groote schouburgh der nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen, 1718-1721, vol. II, p. 237.1 In 1719, the painter Arnold Houbraken voiced his regret about the end of the prosperity that had reigned in the Dutch Republic around the middle of the seventeenth century. He indicates this period as especially favorable to artists and speaks of a ‘golden age for art’ (Gulde Eeuw voor de Konst). But what exactly was Houbraken talking about? The word eeuw is ambiguous: it could refer to the length of a century as well as to an undetermined period, relatively long and historically undefined. In fact, since the sixteenth century, the expression gulde(n) eeuw or goude(n) eeuw referred to two separate realities as they can be distinguished today:2 the ‘golden century’, that is to say a period that is part of history; and the ‘golden age’, a mythical epoch under the reign of Saturn, during which men and women lived like gods, were loved by them, and enjoyed peace and happiness and harmony with nature. -

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of Semester

Reserve Number: E14 Name: Spitz, Ellen Handler Course: HONR 300 Date Off: End of semester Rosenberg, Jakob and Slive, Seymour . Chapter 4: Frans Hals . Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600-1800 . Rosenberg, Jakob, Slive, S.and ter Kuile, E.H. p. 30-47 . Middlesex, England; Baltimore, MD . Penguin Books . 1966, 1972 . Call Number: ND636.R6 1966 . ISBN: . The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or electronic reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or electronic reproduction of copyrighted materials that is to be "used for...private study, scholarship, or research." You may download one copy of such material for your own personal, noncommercial use provided you do not alter or remove any copyright, author attribution, and/or other proprietary notice. Use of this material other than stated above may constitute copyright infringement. http://library.umbc.edu/reserves/staff/bibsheet.php?courseID=5869&reserveID=16583[8/18/2016 12:48:14 PM] f t FRANS HALS: EARLY WORKS 1610-1620 '1;i no. l6II, destroyed in the Second World War; Plate 76n) is now generally accepted 1 as one of Hals' earliest known works. 1 Ifit was really painted by Hals - and it is difficult CHAPTER 4 to name another Dutch artist who used sucli juicy paint and fluent brushwork around li this time - it suggests that at the beginning of his career Hals painted pictures related FRANS HALS i to Van Mander's genre scenes (The Kennis, 1600, Leningrad, Hermitage; Plate 4n) ~ and late religious paintings (Dance round the Golden Calf, 1602, Haarlem, Frans Hals ·1 Early Works: 1610-1620 Museum), as well as pictures of the Prodigal Son by David Vinckboons. -

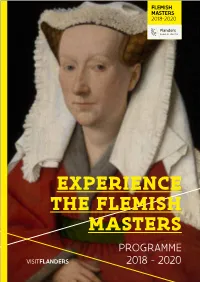

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

"MAN with a BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED to FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION and SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian

Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies Fogg Art Museum Harvard University 1'1 Ii I "MAN WITH A BEER KEG" ATTRIBUTED TO FRANS HALS TECHNICAL EXAMINATION AND SOME ART HISTORICAL COMMENTARIES • by Daniel Fabian July 1984 ___~.~J INDEX Abst act 3 In oduction 4 ans Hals, his school and circle 6 Writings of Carel van Mander Technical examination: A. visual examination 11 B ultra-violet 14 C infra-red 15 D IR-reflectography 15 E painting materials 16 F interpretatio of the X-radiograph 25 G remarks 28 Painting technique in the 17th c 29 Painting technique of the "Man with a Beer Keg" 30 General Observations 34 Comparison to other paintings by Hals 36 Cone usions 39 Appendix 40 Acknowl ement 41 Notes and References 42 Bibliog aphy 51 ---~ I ABSTRACT The "Man with a Beer Keg" attributed to Frans Hals came to the Centre for Conservation and Technical Studies for technical examination, pigment analysis and restoration. A series of samples was taken and cross-sections were prepared. The pigments and the binding medium were identified and compared to the materials readily available in 17th century Holland. Black and white, infra-red and ultra-violet photographs as well as X-radiographs were taken and are discussed. The results of this study were compared to 17th c. materials and techniques and to the literature. 3 INTRODUCTION The "Man with a Beer Keg" (oil on canvas 83cm x 66cm), painted around 1630 - 1633) appears in the literature in 1932. [1] It was discovered in London in 1930. It had been in private hands and was, at the time, celebrated as an example of an unsuspected and startling find of an old master. -

Entertaining Genre of Matthijs Naiveu - Depicting Festivities and Performances at the Dawn of the ‘Theatre Age’

Research Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context Entertaining genre of Matthijs Naiveu - depicting festivities and performances at the dawn of the ‘Theatre Age’. Student: Adele-Marie Dzidzaria 0507954 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Rudi Ekkart Utrecht University 2007 Table of contents Introduction....................................................................................................................3 1 Biography/Overview of Naiveu’s oeuvre ..............................................................5 1.1 From Leiden to Amsterdam...........................................................................5 1.2 From early genre to theatrical compositions..................................................8 1.3 Portraiture ....................................................................................................14 2 Historiographic context/ Theatricality in genre painting.....................................19 3 Naiveu’s genre paintings – innovating on old subjects and specialising in festivities..............................................................................................................24 4 Theatrical paintings - thematic sources and pictorial models..............................32 4.1 Out-door festivities and performances.........................................................32 4.2 In-door celebrations and amusements..........................................................56 5 Conclusion ...........................................................................................................62 -

Verspronck, Johannes Cornelisz Also Known As Sprong, Gerard Dutch, 1606/1609 - 1662

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Verspronck, Johannes Cornelisz Also known as Sprong, Gerard Dutch, 1606/1609 - 1662 BIOGRAPHY The scarcity of documents relating to the life of the portraitist Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck has made securing his date of birth difficult. Though it was long believed that he was born in Haarlem in 1597, recent archival research suggests a date of about a decade later, between 1606 and 1609.[1] Theodorus Schrevelius, the only contemporary author to mention Verspronck, referred to him as Gerard Sprong, thereby contributing to the confusion surrounding the artist’s biography.[2] Nonetheless, some facts about Verspronck’s life remain clear. He was the son of the Haarlem-born painter Cornelis Engelsz (c. 1575–1650), who had trained with Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Dutch, 1562 - 1638) and Karel van Mander I (Netherlandish, 1548 - 1606). Verspronck probably received his first training from his father, though he may have spent a brief period of time in the studio of Frans Hals (Dutch, c. 1582/1583 - 1666). He became a member of the Saint Luke’s Guild in Haarlem in 1632, and shortly thereafter, in 1634, produced his first dated painting. Verspronck never married and lived with his parents for most of his life until he bought a house on the Jansstraat in 1656, where he lived with his brother and sister. Verspronck became quite wealthy as a successful portraitist for Haarlem’s patrician families. He also painted group portraits for civic organizations.[3] Even though Verspronck was a Catholic, he obtained commissions from Calvinist, as well as Catholic, patrons.[4] The only portrait for which the price is known is that of the Catholic priest Augustijn Alsthenius Bloemert, Verspronck’s last known work, dated 1658, for which he received a payment of 60 guilders.[5] Verspronck died in June 1662 and was buried on June 30 in Haarlem’s Saint Bavo Church.