The University of Alberta's Contribution to World War 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada 1919 a Nation Shaped by War Edited by Tim Cook and J.L

Canada 1919 A Nation Shaped by War Edited by Tim Cook and J.L. Granatstein Contents Timeline / viii Introduction / ! Tim Cook and J.L. Granatstein " #e Long "$"$: Hope, Fear, and Normalcy / "% Alan Bowker % Coming Home: How the Soldiers of Canada and Newfoundland Came Back / %& Dean F. Oliver ! “Playing with Fire”: Canadian Repatriation and the Riots of "$"$ / '! William F. Stewart ' New Battlegrounds: Treating VD in Belgium and Germany, "$"(–"$ / )& Lyndsay Rosenthal ) “L’honneur de notre race”: #e %%nd Battalion Returns to Quebec City, "$"$ / &% Serge Marc Dur!inger * Demobilization and Colonialism: Indigenous Homecomings in "$"$ / (* Brian R. MacDowall & Victory at a Cost: General Currie’s Contested Legacy / "+% Tim Cook ( Dealing with the Wounded: #e Evolution of Care on the Home Front to "$"$ / ""& Kandace Bogaert vi Contents $ In Death’s Shadow: #e "$"(–"$ In,uenza Pandemic and War in Canada / "!) Mark Osborne Humphries "+ #e Winnipeg General Strike of "$"$: #e Role of the Veterans / "'( David Jay Bercuson "" #e Group of Seven and the First World War: #e Burlington House Exhibition / "*% Laura Brandon "% Domestic Demobilization: Letters from the Children’s Page / "&& Kristine Alexander "! “At Peace with the Germans, but at War with the Germs”: Canadian Nurse Veterans a.er the First World War / "$+ Mélanie Morin-Pelletier "' A Timid Transformation: #e First World War’s Legacy on Canada’s Federal Government / %+' Je" Keshen ") Politics Undone: #e End of the Two-Party System / %%+ J.L. Granatstein "* Growing Up Autonomous: Canada and Britain through the First World War and into the Peace / %!' Norman Hillmer "& Past Futures: Military Plans of the Canadian and Other Dominion Armies in "$"$ / %'( Douglas E. Delaney "( #e Navy Reborn, an Air Force Created? #e Making of Canadian Defence Policy, "$"$ / %*% Roger Sarty "$ “Our Gallant Employees”: Corporate Commemoration in Postwar Canada / %&( Jonathan F. -

In This Document an Attempt Is Made to Present an Introduction to Adult Board. Reviews the Entire Field of Adult Education. Also

rn DOCUMENT RESUME ED 024 875 AC 002 984 By-Kidd. J. R., Ed Adult Education in Canada. Canadian Association for Adult Education, Toronto (Ontario). Pub Date SO Note- 262p. EDRS Price MF-$1.00 HC-$13.20 Descriptors- *Adult Education Programs. *Adult Leaders, Armed Forces, Bibliographies, BroadcastIndustry, Consumer Education, Educational Radio, Educational Trends, Libraries, ProfessionalAssociations, Program Descriptions, Public Schools. Rural Areas, Universities, Urban Areas Identifier s- *Canada Inthis document an attempt is made to present an introduction toadult education in Canada. The first section surveys the historical background, attemptsto show what have been the objectives of this field, and tries to assessits present position. Section IL which focuses on the relationship amongthe Canadian Association for Adult Education, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and theNational Film Board. reviews the entirefield of adult education. Also covered are university extension services. the People's Library of Nova Scotia,and the roles of schools and specialized organizations. Section III deals1 in some detail, with selected programs the 'Uncommon Schools' which include Frontier College, and BanffSchool of Fine Arts, and the School .of Community Programs. The founders, sponsors, participants,and techniques of Farm Forum are reported in the section on radio andfilms, which examines the origins1 iDurpose, and background for discussionfor Citizens' Forum. the use of documentary films inadult education; Women's Institutes; rural programs such as the Antigonish Movement and theCommunity Life Training Institute. A bibliography of Canadian writing on adult education is included. (n1) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEDFROM THE i PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. -

Proquest Dissertations

Merciless Marches and Martial Law: Canada's Commitment to the Occupation of the Rhineland by Christopher James Hyland B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 B.Ed., University of British Columbia, 2000 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: Marc Milner, PhD, History Examining Board: Steve Turner, PhD, History, Chair Peter C. Kent, PhD, History Alan Sears, PhD, Education This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies University of New Brunswick November, 2007 © Christopher James Hyland, 2007 Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'gdition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-63693-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63693-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliothgque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

DAVID H. TURPIN Installation of the President and Vice-Chancellor November 16, 2015

DAVID H. TURPIN Installation of the President and Vice-Chancellor November 16, 2015 3 A New Chapter in a Proud History Within these walls will be heard the quiet note of the good and the beautiful. Whatever may be the things that appeal to our innermost being, whatever may be the mode of expression by which we may give to the world the highest and the best that is in us, for this we must find a source in our university life.” “ —President Robert Wallace, Installation, October 10, 1928 4 The story of the University of Alberta is a story of humble beginnings and bold ambitions. Those ambitions were evident even before we had a campus, when 45 students, four professors, and our founding president, Henry Marshall Tory, forged the nascent university from its first home at Duggan Street School in what was then the City of Strathcona. These pioneers of higher learning were guided by Tory’s vision of a provincial university committed to the pursuit of whatsoever things are true, creating knowledge not only for its own sake, but also for the uplifting of the whole people. More than a century later, the U of A has remained true to that vision, even as it has transformed into a world-class institution—one that serves not only the citizens of Edmonton and Alberta, but also the people of Canada. Each day, through teaching and learning, through research and discovery, and through the lives of our alumni and the communities they serve, the University of Alberta’s impact is felt across our city, our province, and our country. -

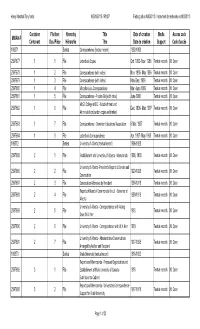

MSS0113 Vols. 1--30.Xls.Xlsx

Henry Marshall Tory fonds MG30-D115 / R1887 Finding aid no MSS0113 / Instrument de recherche no MSS0113 Container File/Item Hierarchy Title Date of creation Media Access code MIKAN # Contenant Dos./Pièce Hiérarchie Titre Date de création Support Code d'accès 109371 Series Correspondence [textual record] 1902-1908 2597677 1 1 File Letterbook Copies Oct. 1902- Nov. 1906 Textual records 90: Open 2597678 1 2 File Correspondence (with index) Nov. 1905- May 1906 Textual records 90: Open 2597679 1 3 File Correspondence (with index) May-Dec. 1906 Textual records 90: Open 2597680 1 4 File Miscellaneous Correspondence Mar.-June 1906 Textual records 90: Open 2597681 1 5 File Correspondence ‐ Private File (with index) June 1906 Textual records 90: Open McGill College of B.C. ‐ Establishment and 2597682 1 6 File Dec. 1906- Mar. 1907 Textual records 90: Open Administration (carbon copies with index) 2597683 1 7 File Correspondence ‐ Dominion Educational Association 6 Mar. 1907 Textual records 90: Open 2597684 1 8 File Letterbook Correspondence Apr. 1907- May 1908 Textual records 90: Open 109372 Series University of Alberta [textual record] 1906-1928 2597685 2 1 File Establishment of a University of Alberta ‐ Memoranda 1906, 1908 Textual records 90: Open University of Alberta ‐President's Reports to Senate and 2597686 2 2 File 1920-1928 Textual records 90: Open Convocation 2597687 2 3 File Convocation Addresses by President 1908-1918 Textual records 90: Open Reports of Board of Governors to the Lt. ‐ Governor of 2597688 2 4 File 1909-1919 Textual records 90: Open Alberta University of Alberta ‐ Correspondence with Acting 2597689 2 5 File 1918 Textual records 90: Open Dean W.A. -

Khaki University Canadian Soldiers Overseas

zA Khaki University FOR Canadian Soldiers Overseas ' i Preliminary Report H. M. TORY, LL.D. President University of Alberta II Advisory Board Representing the Universities of Canada III Further Memorandum by Dr. TORY on Educational Programme for Demobilization This is a reproduction of a book from the McGill University Library collection. Title: A Khaki University for Canadian soldiers Author: Tory, H. M. (Henry Marshall), 1864-1947 Publisher, year: Montreal : Federated Press, [1917?] The pages were digitized as they were. The original book may have contained pages with poor print. Marks, notations, and other marginalia present in the original volume may also appear. For wider or heavier books, a slight curvature to the text on the inside of pages may be noticeable. ISBN of reproduction: 978-1-77096-100-5 This reproduction is intended for personal use only, and may not be reproduced, re-published, or re-distributed commercially. For further information on permission regarding the use of this reproduction contact McGill University Library. McGill University Library www.mcgill.ca/library A Khaki University FOR Canadian Soldiers Overseas i Preliminary Report BY H. M. TORY, LL.D. President University of Alberta II Advisory Board Representing the Universities of Canada III Further Memorandum by Dr. TORY on Educational Programme for Demobilization THE FEDERATED PRESS LIMITED 11-13 Cathedral St., Montreal To LT.-COL. BIRKS, Supervisor of Y.M.C.A., Canadian Overseas Forces. SIR,— In submitting a report on the matter referred to me for study by your Executive, viz., to what extent it would be possible to undertake a definite educational programme among the Soldiers of the Canadian Army, permit me first to make a short statement about the general work of your Association as I saw it in France and England. -

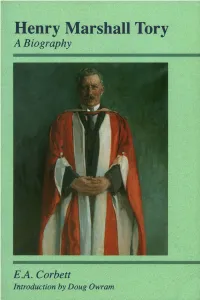

9780888648419 WEB.Pdf

A note about the front matter This eBook contains new introductory material, as well as the original introductory material printed in 1954. To navigate to the new Foreword, Acknowledgements and Introduction, please use the electronic Table of Contents that appears alongside the eBook. To navigate through the remainder of the book, you may use the electronic Table of Contents or type the page number in the "page #" box at the top of the screen and click "Go." For citation purposes, use the page numbers that appear in the text. HENRY MARSHALL TORY Henry Marshall Tory in 1925. University of Alberta Archives. Henry Marshall Tory A Biography E.A. CORBETT With a New Introduction by DOUG OWRAM Foreword by CHANCELLOR SANDY A. MACTAGGART THE UNIVERSITY OF ALBERTA PRESS This edition published by The University of Alberta Press Athabasca Hall Edmonton, Alberta Canada T6G 2E8 Copyright © this edition by The University of Alberta Press 1992. Originally published as Henry Marshall Tory: Beloved Canadian in 1954 by The Ryerson Press, Toronto, Ontario. Reissued by permission of Paul D. Corbett and Joan Corbett Fairfield. ISBN 0-88864-250-4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Corbett, E.A. (Edward Annand), 1884-1964. Henry Marshall Tory: a biography Originally published: Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1954 Included bibliographical references ISBN 0-88864-254-0 1. Tory, H.M. (Henry Marshall), 1864-1947. 2. Educators—Canada—Biography. 3. Education, Higher—Canada—History. I. Title. LA2325.T6C67 1992 378.7T092 C92-091395-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any forms or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copy- right owner. -

GOING to WAR in KOREA Peacekeeping in the Congo

CANADA REMEMBERS TIMES Veterans’ Week Special Edition – 5-11 November 2020 REMEMBERING THE NETHERLANDS V-E Day V-J DAY AND at last! FREEDOM The Second World War was the Some 10,000 Canadians served in Asia bloodiest conflict in human history. during the Second World War. This It began in September 1939 and the included almost 2,000 soldiers from fighting in Europe would rage until Manitoba’s Winnipeg Grenadiers and May 1945. Canada joined many other Quebec’s Royal Rifles of Canada who countries to form the Allied powers were sent across the Pacific Ocean in which fought to restore peace and the fall of 1941 to help defend the British freedom to the continent. colony of Hong Kong. Our soldiers, sailors and aviators The Japanese invaded Hong Kong on Image: Library PA-136176 Canada Image: and Archives played an important role in helping 8 December 1941. Badly outnumbered, Dutch residents welcome Canadian soldiers after the liberation of the town of Zwolle on 14 April 1945. achieve victory. As the war neared the defenders fought bravely before its end, Canadian troops took part being forced to surrender on Christmas The Liberation of the Netherlands Robert Greene recalled of the liberation of in the bitter campaign in Northwest Day. Approximately 290 Canadians were during the Second World War was the town of Emmelo: Europe in 1944 and 1945. They saw killed and almost 500 wounded. The one of the best-known chapters in our heavy action in France, Belgium, the survivors’ ordeal was just beginning. country’s long military history. -

Download Download

"The Fight ofMy Life": 1 Alfred Fitzpatrick andFrontier College's Extramural Degree for Working People George L. Cook with Marjorie Robinson* From 1922 to 1932, Frontier College was an "open" and "national" institution of higher education, which was empowered to award degrees to working people without access to the established universities. This experiment was the brain-child of Frontier College's founder, Alfred Fitzpatrick (1862-1936), aformer Presbytarian cleric inspired by the "social gospel" , who championed Canada's campmen and manuallabourers. With minimal resources and without a mature institutional structure, Fitzpatrick developed a Board ofExaminers composed ofscholars drawn from across the country's English and French universities and created an extramural degree programme which was, in fact, unique in the English-speaking world. However, Frontier College soon met effective opposition and, thus, the flowering of greater popular access to higher education was delayed until after the Second World War. De 1922 à 1932, Frontier College était un établissement « ouvert» et « national» d'enseignement supérieur habilité à décerner des grades aux travailleurs qui n'avaient pas accès aux universités reconnues. Cette initiative originale était due à Alfred Fitzpatrick (1862-1936), un ancien ecclésiastique presbytérien qu'animait l'esprit de l' « évangile sociale» et qui s'était fait le défenseur de ceux qui travaillaient sur les chantiers et des ouvriers. Disposant de maigres ressources et sans structure ins titutionnelle éprouvée, Fitzpatrick mis sur pied une commission d'examen qui regroupait des spécialistes venant d'universités francophones et anglophones de partout au pays et créa un programme « extra-muros » menant à un diplôme. -

General Sir Arthur Currie Collection Archives Finding Aid 19801226

General Sir Arthur Currie Collection Archives Finding Aid 19801226 By: Barbara Wilson (1998) Revised by: Matt Kulka (2001) Table of Contents Biographical Information Page 3 Item Notes and Titles Page 4 Documents renumbered into new item collections Page 6 Documents transferred into Photo-Archives Page 8 Related documents found in Currie Collection Page 9 General Sir Arthur Currie Finding Aid 19801226-038 58A 1 59.1 Page 10 19801226-266 58A 1 59.2 Page 10 19801226-267 58A 1 59.3 Page 10 19801226-268 58A 1 59.4 Page 10 19801226-269 58A 1 59.5 Page 12 19801226-270 58A 1 59.6 Page 14 19801226-271 58A 1 59.7 Page 15 19801226-272 58A 1 60.1 Page 16 19801226-273 58A 1 60.2 Page 18 19801226-274 58A 1 60.3 Page 21 19801226-275 58A 1 60.4 Page 24 19801226-276 58A 1 60.5 Page 26 19801226-277 58A 1 60.6 Page 28 19801226-278 58A 1 61.1 Page 31 19801226-279 58A 1 61.2 Page 35 19801226-280 58A 1 61.3 Page 40 19801226-281 58A 1 61.4 Page 43 19801226-282 58A 1 61.5 Page 48 19801226-283 58A 1 61.6 Page 50 19801226-284 58A 1 61.7 Page 52 19801226-285 58A 1 61.8 Page 54 19801226-286 58A 1 62.1 Page 56 19801226-287 58A 1 62.2 Page 57 Examples of documents found in Currie Collection Page 59 2 General Sir Arthur William Currie (1875-1933) Currie, Sir Arthur William b. -

The Crucial Role of Universities in Canada's Knowledge Economy

Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, Issue #178, August 5, 2016. © by CJEAP and the author(s). FINANCING CANADIAN UNIVERSITIES: MAJOR CHANGES SINCE 18021 Franz W. Nentwich Universities began operating in the present borders of Canada in 1802. As annual enrolments grew to 1,147,233 in 2012, so too did university expenditures. Government contributions to university revenues fluctuated from 62% in 1920 to 46% in 1935, reaching a high of 81% in the mid- to late 1970s, then falling to 48% in 2014. Annual university revenues increased about 275 times between 1920 and 2014 (in constant 2014 dollars), from $129.3 million to $35.5 billion. In the two centuries between 1813 and 2013, undergraduate fees (in constant 2013 dollars) increased by a factor of 24, from $236 to $5,720. “Follow the money!” This was the suggestion of an anonymous informant in the movie “All the President’s Men,” after one journalist lamented that “All we’ve got is pieces. We can’t seem to figure out what the puzzle is supposed to look like.” Similarly, anyone researching the financing of Canadian universities will find a difficult puzzle to solve, with each province being a different piece of the financial puzzle. Of course, the general features are well known. For instance, in 2009, 6.6% of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) was spent on all educational institutions, slightly more than the average of 6.3% for OECD countries, with 2.7% flowing to all tertiary education institutions (universities and community colleges combined), more than the 2.1% spent in 1995 or the 2.3% in 2000 (OECD, 2013). -

The Khaki University of Canada” in the Great War

“The Khaki University of Canada” in The Great War The British army had recognised the value of basic education for serving soldiers during the nineteenth century. The Corps of Army Schoolmasters was formed on 2nd July 1845 and offered schooling at an elementary level for reading and arithmetic. It was believed that these skills would help soldiers to obtain employment after their military service ended. The concept of military education was adopted by the Canadians between 1917 and 1919 but then raised to a whole new level. The model was so successful that it created interest amongst other allied countries such as Australia and New Zealand. The Khaki University of Canada developed through the often conflicting efforts of the YMCA and the Chaplains Service. In November 1851 a new organisation named ‘The Young Men’s Christian Association’ opened at Montreal in Quebec. Its aims were to provide a Christian fellowship to all, regardless of faith or beliefs. From the outset, the YMCA offered care and help to anyone who needed it. By 1914, the ‘Y’ had become a huge international network of branches. The Canadian YMCA was to play a major vital support role for all service men and spared no effort or resources to help provide them with a brief respite whenever and wherever possible. Whether at the front lines, in Great Britain or back home in Canada, the organisation set up makeshift centres in huts, halls, dugouts and tents. From there they offered an oasis for rest, recreation and a few home comforts. These were especially appreciated by men who were away from home for the first time.