The Third Battle of Ypres by Jon Sandison I Met, Before I Went To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trinity College War Memorial Mcmxiv–Mcmxviii

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXIV–MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Hebrews 11: 13 Adamson, William at Trinity June 25 1909; BA 1912. Lieutenant, 16th Lancers, ‘C’ Squadron. Wounded; twice mentioned in despatches. Born Nov 23 1884 at Sunderland, Northumberland. Son of Died April 8 1918 of wounds received in action. Buried at William Adamson of Langham Tower, Sunderland. School: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France. UWL, FWR, CWGC Sherborne. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1904; BA 1907; MA 1911. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancshire Allen, Melville Richard Howell Agnew Regiment, 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April 24 1916. Commemorated at Basra Memorial, Iraq. UWL, FWR, CWGC Born Aug 8 1891 in Barnes, London. Son of Richard William Allen. School: Harrow. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity Addy, James Carlton Oct 1 1910. Aviator’s Certificate Dec 22 1914. Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal Flying Corps. Killed in flying Born Oct 19 1890 at Felkirk, West Riding, Yorkshire. Son of accident March 21 1917. Buried at Bedford Cemetery, Beds. James Jenkin Addy of ‘Carlton’, Holbeck Hill, Scarborough, UWL, FWR, CWGC Yorks. School: Shrewsbury. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1910; BA 1913. Captain, Temporary Major, East Allom, Charles Cedric Gordon Yorkshire Regiment. Military Cross. -

Powys War Memorials Project Officer, Us Live with Its Long-Term Impacts

How to use this toolkit This toolkit helps local communities to record and research 4 Recording and looking after war memorials their First World War memorials. Condition of memorials Preparing a Conservation Maintenance Plan It includes information about the war, the different types of memorials Involving the community and how communities can record, research and care for their memorials. Grants It also includes case studies of five communities who have researched and produced fascinating materials about their memorials and the people they 5 Researching war memorials, the war and its stories commemorate. Finding out more about the people on the memorials The toolkit is divided into seven sections: Top tips for researching Useful websites 1 Commemorating the centenary of the First World War Places to find out more Tips from the experts 2 The First World War Regiments in Wales A truly global conflict Gathering local stories How did it all begin? A very short history of the war 6 What to do with the information Wales and the First World War A leaflet The men of Powys An interpretive panel Effects of war on communities and survivors An exhibition Why so many memorials? A First World War trail Memorials in Powys A poetry competition Poetry and musical events 3 War memorials What is a war memorial? 7 Case studies History of war memorials Brecon University of the Third Age Family History Group Types of war memorial Newtown Local History Group Symbolism of memorials Ystradgynlais Library Epitaphs The YEARGroup Materials used in war memorials L.L.A.N.I. Ltd Who is commemorated on memorials? How the names were recorded Just click on the tags below to move between the sections… 1 and were deeply affected by their experiences, sometimes for the rest Commemorating of their lives. -

The War Poet - Francis Ledwidge

Volume XXXIX, No. 7 • September (Fómhair), 2013 The War Poet - Francis Ledwidge .........................................................................................................On my wall sits a batik by my old Frank fell in love with Ellie Vaughey, one looked at familiar things seen thus for friend, Donegal artist Fintan Gogarty, with the sister of his friend, Paddy. Of her, he the first time. I wrote to him greeting him a mountain and lake scene. Inset in the would write, as a true poet, which indeed he was . .” piece is a poem, “Ardan Mor.” The poem “I wait the calling of the orchard maid, Frank was also involved in the arts in reads, Only I feel that she will come in blue, both Dublin and Slane. He was involved As I was climbing Ardan Mór With yellow on her hair, and two curls in many aspects of the local community From the shore of Sheelin lake, strayed and was a natural leader and innovator. He I met the herons coming down Out of her comb's loose stocks, and I founded the Slane Drama Group in which Before the water’s wake. shall steal he was actor and producer. And they were talking in their flight Behind and lay my hands upon her eyes.” In 1913, Ledwidge would form a branch Of dreamy ways the herons go At the same time, the poetry muse of the Irish Volunteers, or Óglaigh na When all the hills are withered up encompassed the being of young Frank. hÉireann. The Volunteers included members Nor any waters flow. He would write poems constantly, and in of the Gaelic League, Ancient Order of The words are by Francis Ledwidge, an 1912, mailed a number of them to Lord Hibernians and Sinn Féin, as well as mem- Irish poet. -

Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon

111: Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon Basic Information [as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC] Name as recorded on local memorial or by CWGC: Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon Rank: Lieutenant Battalion / Regiment: 14th Bn. Royal Welsh Fusiliers Service Number: Date of Death: 4 August 1917 Age at Death: 34 Buried / Commemorated at: Bard Cottage Cemetery, Ypres (Ieper), Arrondissement Ieper, West Flanders Belgium Additional information given by CWGC: The son of Thomas and Anna Elizabeth Apsimon, of 107, Liscard Rd., Wallasey. Native of Liverpool. Arthur Tryweryn Apsimon was born in April 1883 in the Toxteth Park district of Liverpool, the third of four sons of Thomas and Anne Elizabeth Apsimon. It is not known where or when Thomas and Anne married but, at the time of the 1881 census, two years before Arthur was born, they were living in Toxteth Park with their two young sons although Thomas was not in the household on census night: 1881 census (extract) – 14, Amberley Street, Toxteth Park, Liverpool Anne E. Apsimon 27 milling engineer’s wife born America, New York Joseph H. 1 year 10 months born Liverpool Thomas T. 5 months born Liverpool Bertha Upton 19 servant, nurse born Liverpool Catherine James 18 general servant born Cardiganshire Amberley Street exists now only as the entrance to the car park of the Merseyside Caribbean Council Community Centre to the west of the junction of Upper Parliament Street and Mulgrave Street. The family had moved to Birkdale, near Southport, by 1885 when their last child, Estyn Douglas Apsimon, was born but at the time of the 1891 census they were living near Sowerby Bridge in the Upper Calder valley in West Yorkshire. -

Ieper: Daguitstap 11/11/2007

Ieper De Groote Oorlog 1914 - 1918 11 november 2007 Remembrance Day Programma 08u45 Herdenkingshulde op de Franse militaire begraafplaats Saint-Charles de Potyze in Ieper. 09u30 Koffie in café-restaurant Kom Il Foo, Tempelstraat 7 in Ieper. 10u15 Vertrek via de Grote Markt naar de Menenpoort. 10u20 Vertrek “Poppy Parade” naar de Menenpoort 10u30 Vertrek optocht met de Koninklijke Harmonie “Ypriana” 11u00 Speciale Last Post plechtigheid onder de Menenpoort, opgeluisterd door het Sint-Niklaas mannenkoor en the Choir of Holy Trinity uit Dartford (UK). 12u15 We wandelen van de Menenpoort via de vestingroute naar Ramparts Cemetery aan de Rijselpoort. 13u15 Lunch in Kom Il Foo. 14u00 Bezoek aan Essex Farm Cemetery, de Kanaalsite John Mc Crae en het gedenkteken voor de 49ste (West Riding) Divisie, Boezinge. 16u00 Terugkeer naar de kathedraal van Ieper. 16u30 Herdenkingsconcert in de Sint-Maartenskathedraal, Ieper. “The Great War Remembered” 18u30 Wandeling in en rond de sfeervol verlichte Lakenhalle. Drink in een café op de Grote Markt. 20u00 Speciale Last Post plechtigheid onder de Menenpoort. Bij regenweer vervalt het namiddagprogramma en bezoeken we van 14u00 tot 16u00 het “In Flanders Fields”-museum in de Lakenhallen. - 1 - De Groote Oorlog De Eerste Wereldoorlog duurde voor België van 4 augustus 1914 tot 11 november 1918. Het was het eerste conflict waar naties van alle continenten direct of indirect bij betrokken waren. Hij bracht vooral voor Europa zoveel vernieling en zulke enorme aantallen doden met zich mee dat de overlevenden hem de “Groote Oorlog” noemden. Eén van de belangrijkste slagvelden was het westelijk front, een smalle strook waar in de herfst van 1914 de stormloop van het Duitse leger was vastgelopen en de legers zich in diepe loopgraven hadden ingegraven. -

Fighting for Every Metre of High Ground

WWI Sal the ien t C e n t 2014 e n a r IEPER y YPRES YPERN Walking folder Ypres Salient-North / Entry point Klein Zwaanhof Three entry points in the Ypres Salient 2018 The story of the Great War is told in an interactive and contemporary way in the In Flanders Fields Museum in the Cloth Hall in Ieper. The museum also explains how the landscape has become the last witness of these four terrible years of fighting. To help you to explore this Fighting for every landscape, you can make use of three entry points created along the old front line of the Ypres Salient: in the north at Klein Zwaanhof (Little Swan Farm); in the east at Hooge Crater Museum; and in the south near Hill 60 and the Palingbeek provincial park. Remembrance metre of high ground trees mark the positions of the two front lines between the entry points. A 2.8 kilometre walk along the front line in the northern part of the Ypres Salient Entry point Klein Zwaanhof ››› The small, original cemeteries The front line at Caesar’s Nose ››› Fortin 17: gentle slopes become hills of blood The Writers’ Path: poets and authors at the front Ypres Salient cycle route Yorkshire Trench and Deep Dug-Out People who prefer to explore the old battlefield by bike can follow theYpres Salient cycle route. This 35-kilometre route starts and ends at the Cloth Hall on the Market Square (Grote Markt) in Ieper. The route links the three entry points: north, east and south. It also passes many other sites of interest related to the First World War. -

Weatherman Walking Flanders Fields

bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2016 Weatherman Walking Flanders Fields Location: Ypres (Leper) in Belgium 4 Locations are given in latitude and longitude. 5 6 7 8 3 10 9 N 11 W E S 50.70616, 2.92768 2 1 12 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to help you walk the route. We recommend using a detailed map of the area in conjunction with this guide. Routes and conditions may have changed since this guide was written. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and footwear and check 1 weather conditions before heading out. bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2016 Weatherman Walking Flanders Fields The small Belgian town of Ypres was a key battlefi eld throughout World War One. It was where the British stopped the German advance in autumn 1914 and was the site of a series of battles, the most famous being at the nearby village of Passchendaele. By the end of the war in 1918 the town had been virtually destroyed. The places Derek visited are both in the town and in the surrounding area. While the town of Ypres is easy to walk around the other locations are several miles away, so we recommend going there by car or coach. All are open to the public and easily accessible. Note that the spellings of place names are in both French and Flemish. We’ve listed both here. 1 Geluveld (Gheluvelt) and the First Battle of Ypres (50.83455, 2.99447) Geluveld is situated on the Menin (Menen) Road (N8) approximately 5 miles (8km) from the centre of Ypres. -

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXIV-MCMXVIII Iuxta Fidem

TRINITY COLLEGE MCMXIV-MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. (The Vulgate has ‘supra terram’, and includes the ‘eas’ which is missing from the inscription.) These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. (Hebrews 11: 13) Any further details of those commemorated would be gratefully received: please contact [email protected]. Details of those who appear not to have lost their lives in the First World War, e.g. Philip Gold, are given in italics. Adamson, William Allen, Melville Richard Howell Armstrong, Michael Richard Leader Born Nov. 23, 1884 at Sunderland, Agnew Born Nov. 27, 1889, at Armagh, Ireland. Northumberland. Son of William Adamson, Son of Henry Bruce Armstrong, of Deans Born Aug. 8, 1891, in Barnes, London. Son of Langham Tower, Sunderland., Sherborne Hill, Armagh. School, Cheltenham College. of Richard William Allen. Harrow School. School. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, June 25, Admitted as pensioner at Trinity, Oct. 1, June 25, 1904. BA 1907, MA 1911. 1908 (Mechanical Science Tripos). BA 1910. Aviator’s Certificate, Dec. 22, 1914. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancs. Regiment, 1911. 2nd Lieutenant, Royal Field Artillery Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April and Royal Engineers (150th Field Flying Corps. Killed in flying accident, 24, 1916. Commemorated at Basra Company). -

Valentine Joe Strudwick (Pupil 1903 – C.1913) St Paul’S School’S Boy Soldier

Valentine Joe Strudwick (pupil 1903 – c.1913) St Paul’s School’s Boy Soldier A major embarrassment to the military authorities during the First World War was the presence of boy soldiers at the Front. Officially, the minimum age for army recruits was 19, but children as young as 13 are known to have joined up, lying about their age in order to fight in the trenches against Germany. One such young recruit was Valentine Joe Strudwick. Born on 14 February 1900, Joe was the second of six surviving children of Jesse Strudwick, a gardener, and his second wife Louisa (nee Fuller), a laundress. Jesse’s first wife, Ellen, had died leaving him with two small daughters – stepsisters to Joe. When Joe was born the family lived in Falkland Road, moving later to Orchard Road. At the tender age of three Joe started at the Falkland Road Infants’ School, the Infants’ School that had merged with St Paul’s School in 1896, and he transferred to St Paul’s School at the age of eight, where he would most likely have stayed until the age of 13. After leaving school, Joe is thought to have worked for his uncle, a local coal merchant. He may also have been a farm hand at a smallholding behind St Paul’s School near the Glory Wood. Like many others, however, Joe must have been struck by the persuasive recruitment campaigns run by the British Government from 1914 onwards - poster campaigns designed to encourage men to join up and serve their country. Hundreds of thousands answered the Government’s call, including many young men who thought that army life would provide opportunities for travel and work that were not available at home. -

15. the Destruction of Old Chemical Munitions in Belgium

15. The destruction of old chemical munitions in Belgium JEAN PASCAL ZANDERS I. Chemical warfare in Belgium in World War I During World War I the northernmost part of the front line cut through the Belgian province of West Vlaanderen, running roughly from the coastal town of Nieuwpoort on the Yzer estuary over Diksmuide and Ypres to the French border.1 Both ends of the front line were alternately occupied by British and French troops, with Belgian forces holding the centre. In February 1918 the area controlled by Belgian troops extended to the North Sea, and by June Bel- gian forces held most of the Ypres salient. The front was relatively static until the final series of Allied offensives late in 1918. After the First Battle of Ypres (autumn 1914), which frustrated German hopes of capturing the French Chan- nel ports, the Belgian front remained calm although interrupted by some violent fighting, particularly in the Ypres salient (e.g., the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915, the Third Battle of Ypres in the summer of 1917 and the Allied breakout in 1918). In addition, Belgium assisted Britain and France in their major offensives in France. That assistance consisted of limited actions, such as raids or artillery duels, to occupy German troops.2 However, the flood- ing of the Yzer River to halt the German advance in 1914 meant that the area was not suitable for offensive operations. The relative quiet of the battlefront and the resulting hope of surprise proba- bly explain why experiments with new toxic substances were carried out in Flanders. -

Abersychan Roll of Honour

Abersychan World War One Roll of Honour This Roll of Honour was produced by volunteers from Coleg Gwent, as part of the Heritage Lottery Funded Sharing Private O’Brien project, using several sources including: Pontypool and Abersychan War Memorial unveiling ceremo- ny pamphlet (D2824/6), the Free Press of Monmouthshire and the accompanying index of deaths compiled by the Friends of Gwent Record Office, the Gwent Roll of Honour compiled by Gwent Family History Society, the Common- wealth War Graves Commission website, and service records, census, births, marriages and deaths etc. available on Find My Past and Ancestry Library. If you know of anybody from Abersychan and area who died in WWI and who does not appear on the list please let us know. We can be contacted at [email protected]. Allen, Alfred Joseph: Ordinary Seaman, J 86305, Royal Navy. Alfred was born in 1899 at Talywain and died on 18 April 1918 at Plymouth Royal Naval Hospital from cerebro spinal fever while serving on HMS Viv- id I shore training establishment. He was the son of Emily of 7 Woodlands, Talywain. Alfred was a member of St. Francis Roman Catholic Church and worked as a collier at Lower Varteg Colliery before enlisting in the Royal Navy in March 1918. He is buried at Plymouth, Devonport and Stonehouse Cemetery, Plymouth and commemorated on Pontypool and Abersychan Memorial Gates. Amos, Albert Edward: Private 8323, South Wales Borderers, 1st Battalion. Private Albert Amos died of wounds on the 3rd No- vember 1914. He was 35 years of age and came from Garndiffaith and was the son of Mr George and Mary Amos. -

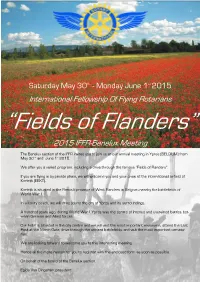

Fields of Flanders” 2015 IFFR-Benelux Meeting

Saturday May 30th - Monday June 1st 2015 International Fellowship Of Flying Rotarians “Fields of Flanders” 2015 IFFR-Benelux Meeting The Benelux section of the IFFR invites you to join us at our annual meeting in Ypres (BELGIUM) from May 30 th and June 1st 2015. We offer you a varied program, including a drive through the famous “Fields of Flanders”. If you are flying in by private plane, we will welcome you and your crew at the international airfield of Kortrijk (EBKT). Kortrijk is situated in the Flemish province of West Flanders in Belgium nearby the battlefields of World War I. In a luxury coach, we will drive you to the city of Ypres and its surroundings. A hundred years ago, during World War I, Ypres was the centre of intense and sustained battles bet- ween German and Allied forces. Our hotel is situated in the city centre and we will visit the most important museums, attend the Last Post at the Menin Gate, drive through the ancient battlefields and visit the most important cemeta- ries. We are looking forward to welcome you to this interesting meeting. Hence all the more reason for you to register with the enclosed form as soon as possible. On behalf of the board of the Benelux section, Egide Van Dingenen, president. IFFR Benelux meeting 2015 : “FIELDS of FLANDERS” - PROGRAM Saturday May 30 th 2015 - arrival Our destination is situated in the western part of Belgium. 12.00-14.00 hrs. : arrivals at EBKT, Kortrijk International Airport. You should land no later than 14.00 hrs.