Red Owl's Legacy Gregory M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 Free

FREE DAREDEVIL: ULTIMATE COLLECTION VOLUME 1 PDF Ed Brubaker,Michael Lark,David Aja | 304 pages | 08 Feb 2012 | Marvel Comics | 9780785163343 | English | New York, United States Softcover Daredevil No Collectible Graphic Novels & TPBs for sale | eBay Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. David W. Mack Illustrator. Alex Maleev Illustrator. During a character-defining run, Brian Michael Bendis crafted a pulp-fiction narrative that exploited the Man Without Fear's rich tapestry of Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 and psychodrama, and resolved them in an incredibly nuanced, modern approach. Now, this Eisner Award-winning run is collected across three titanic trade paperbacks In this volume, witness the Kingpin's downfall at the hand During a character-defining run, Brian Michael Bendis crafted a Daredevil: Ultimate Collection Volume 1 narrative that exploited the Man Without Fear's rich tapestry of characters and psychodrama, and resolved them in an incredibly nuanced, modern approach. Now, this Eisner Award- winning run is collected across three titanic trade paperbacks In this volume, witness the Kingpin's downfall at the hands of Sammy Silke and see how a down-on-his-luck FBI agent can change Matt's life forever. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 2. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

The Only Way Is Down: Lark and Brubaker's Saga As '70S Cinematic

The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir an Essay by Ryan K Lindsay from THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS: EXAMINING MATT MURDOCK AND DAREDEVIL EDITED BY RYAN K. LINDSAY SEQUART RESEARCH & LITERACY ORGANIZATION EDWARDSVILLE, ILLINOIS The Devil is in the Details: Examining Matt Murdock and Daredevil Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay Copyright © 2013 by the respective authors. Daredevil and related characters are trademarks of Marvel Comics © 2013. First edition, February 2013, ISBN 978-0-5780-7373-6. All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts used for review or scholarly purposes, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever, including electronic, without express consent of the publisher. Cover by Alice Lynch. Book design by Julian Darius. Interior art is © Marvel Comics; please visit marvel.com. Published by Sequart Research & Literacy Organization. Edited by Ryan K. Lindsay. Assistant edited by Hannah Means-Shannon. For more information about other titles in this series, visit sequart.org/books. The Only Way is Down: Lark and Brubaker’s Saga as ’70s Cinematic Noir by Ryan K Lindsay Cultural knowledge indicates that Daredevil is the noir character of the Marvel Universe. This assumption is an unchallenged perception that doesn’t actually hold much water under any major scrutiny. If you add up all of Daredevil’s issues to date, the vast majority are not “noir.” Mild examination exposes Daredevil as one of the most diverse characters who has ever been written across a series of genres, from swashbuckling romance, to absurd space opera, to straight up super-heroism and, often, to crime saga. -

The Lawyer As Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts

Barry University School of Law Digital Commons @ Barry Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 5-2019 The Lawyer as Superhero: How Marvel Comics' Daredevil Depicts the American Court System and Legal Practice Louis Michael Rosen Barry University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/facultyscholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation 47 Capital U. L. Rev. 379 (2019) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. THE LAWYER AS SUPERHERO: HOW MARVEL COMICS’ DAREDEVIL DEPICTS THE AMERICAN COURT SYSTEM AND LEGAL PRACTICE LOUIS MICHAEL ROSEN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 380 II. BACKGROUND: POPULAR CULTURE AND THE LAW THEORIES ....... 387 III. DAREDEVIL––THE STORY SO FAR ............................................... 391 A. Daredevil in the Sights of Frank Miller ....................................... 391 B. Daredevil Through the Eyes of Brian Michael Bendis ................ 395 C. Daredevil’s Journey to Redemption by David Hine .................... 402 D. Daredevil Goes Public, by Mark Waid ........................................ 406 IV. DAREDEVIL’S FRESH START AND BIGGEST CASE EVER, BY CHARLES SOULE ...................................................................................... 417 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 430 Copyright © 2019, Louis Michael Rosen. * Louis Michael Rosen is a Reference Librarian and Associate Professor of Law Library at Barry University School of Law in Orlando, Florida. He would like to thank Professor Taylor Simpson-Wood, his mentor, ally, advocate, cheerleader, and ever-patient editor as he wrote this article. -

PDF Download Green Owl Vol. 2 : Friends and Enemies

GREEN OWL VOL. 2 : FRIENDS AND ENEMIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Brian M Osbourn | 110 pages | 02 Jan 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781505924183 | English | none Green Owl Vol. 2 : Friends and Enemies PDF Book Some of them collected together and became vortexes of barely containable power, creating inter-dimensional gateways. Bor Burison. Doctor Who Magazine , Venom: Separation Anxiety 2 , Wally comments, however, that they would be better as friends than enemies. Incredible Hulk , He quickly realizes that Mjolnir has vanished, and fears the otherworldly lightning had an effect on his hammer. X-Men 17 , This wiki All wikis. Crimson Dynamo I. The lightning effect throws energy all around and stuns Thor himself. Inklings welcomes and encourages signed lettersto-the- editor. Back on Earth, Captain America is fighting Bane. Captain Marvel. Categories :. The recent earthquake that took place in California offered us insight as to what would happen to the U. Disney's Aladdin 7 , Which ironically shows, winning a Pulitzer is easier than passing a political satire through Apple. Multiple studies done throughout the years have proven the effects of smoking to be harmful. But they have learned the futility of facing each other in a head-to-head struggle. Wolverine Vol 2 90 , English indie group wraps-up successful Humbug Tour in U. Paul Neary Josef Rubinstein. Savage Sword of Conan , The Lady Bulldogs were able to defeat all three teams. It is the novelty of the experience that makes it worthwhile. Moon Knight. Marvel Comics Presents , Nightmare 3 , Elektra 2 , They were called "Brothers", although they were also sisters, sexless, and everything in between. -

Dk Education Readinglevels Gui

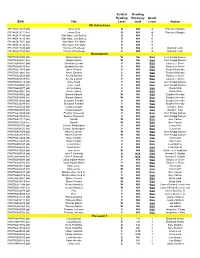

Guided Reading Reading Recovery Grade ISBN Title Level level Level Author DK Adventures 9781465417237 (pb) Horse Club Q N/A 4 Patricia J Murphy 9781465418111 (hc) Horse Club Q N/A 4 Patricia J Murphy 9781465417244 (pb) Star Wars: Jedi Battles U N/A 5 9781465418135 (hc) Star Wars: Jedi Battles U N/A 5 9781465417251 (pb) Star Wars: Sith Wars U N/A 5 9781465418142 (hc) Star Wars: Sith Wars U N/A 5 9781465417220 (pb) Terrors of the Deep S N/A 4 Deborah Lock 9781465418128 (hc) Terrors of the Deep S N/A 4 Deborah Lock Biographies 9780756652098 (pb) Abigail Adams W NA 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756652081 (hc) Abigail Adams W NA 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756608347 (pb) Abraham Lincoln V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756608330 (hc) Abraham Lincoln V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756612470 (pb) Albert Einstein V N/A 5&6 Frieda Wishinsky 9780756612481 (hc) Albert Einstein V N/A 5&6 Frieda Wishinsky 9780756625528 (pb) Amelia Earhart V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756625535 (hc) Amelia Earhart V N/A 5&6 Tanya Lee Stone 9780756603410 (pb) Anne Frank V N/A 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756604905 (hc) Anne Frank V N/A 5&6 Kem Knapp Sawyer 9780756629977 (pb) Annie Oakley V N/A 5&6 Chuck Wills 9780756629861 (hc) Annie Oakley V N/A 5&6 Chuck Wills 9780756658052 (pb) Barack Obama W NA 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756658045 (hc) Barack Obama W NA 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756635282 (pb) Benjamin Franklin V N/A 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756635299 (hc) Benjamin Franklin V N/A 5&6 Stephen Krensky 9780756625542 (pb) Charles Darwin W N/A 5&6 David C. -

Reinstein Woods Unit Management Plan Appendices

Appendix 1 Appendix 1: Selected List of Flora & Fauna The following is a selected list of fauna and flora that may be found within the Dr. Victor Reinstein Woods Nature Preserve. The list includes species observed by past and present DEC resident staff and educators, volunteers, and species recorded during various studies conducted at the Woods by outside researchers (see references for some publications). An investigation conducted in the mid-1990s by the New York Natural Heritage Program found no rare plants or animals in the Woods; however, two species on the Program watch list were documented: jack pine and winged monkeyflower. Threatened or species of special concern in New York State (see endnotes for definitions of these terms) that use the Woods include least bittern, Cooper’s hawk and American bittern. Migrant birds known to stop at the Woods include osprey (a species of special concern) and pied-billed grebe (a threatened species). Other species previously recorded at the Woods that are of special concern include the Jefferson salamander, common loon, sharp-shinned hawk, and common nighthawk. I. Fish Blacknose dace Rhinichthys atratulus Bluegill Lepomis macrochirus Bluntnose minnow Pimephales notatus Brook stickleback Culaea inconstans Brown bullhead Ameiurus nebulosus Central mudminnow Umbra limi Central stoneroller Campostoma anomalum Creek chub Semotilus atromaculatus Fathead minnow Pimephales promelas Green sunfish Lepomis cyanellus Golden shiner Notemigonus crysoleucas Johnny darter Etheostoma nigrum Iowa darter Etheostoma -

X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2015 X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media Lyndsey E. Shelton Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shelton, Lyndsey E., "X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media" (2015). University Honors Program Theses. 146. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/146 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. X-Men, Dragon Age, and Religion: Representations of Religion and the Religious in Comic Books, Video Games, and Their Related Media An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in International Studies. By Lyndsey Erin Shelton Under the mentorship of Dr. Darin H. Van Tassell ABSTRACT It is a widely accepted notion that a child can only be called stupid for so long before they believe it, can only be treated in a particular way for so long before that is the only way that they know. Why is that notion never applied to how we treat, address, and present religion and the religious to children and young adults? In recent years, questions have been continuously brought up about how we portray violence, sexuality, gender, race, and many other issues in popular media directed towards young people, particularly video games. -

The Princedom of Novashan Your Source for News From

The June 25th, 1010 Vol. 23 Issue #4 your source for news from The Princedom of Novashan A Very Special Contents this Issue: Why Slander My Good Issue Written Why Slander My Good Name? Primarily By You, Name? by Rhyvhaad Khan’Ubar by Rhyvhaad Khan’Ubar 1 The Readers. have just finished reading the to Lobstrocity Strikes! latest edition in the Mystic the by Albert Helmenstine 2 Quill,I and I am extremely in- peo- My Studies of Dragons sulted and distraught over the ple of these lands, some fraud decid- by Ciruelo Cabral 2 unwarranted and completely falsified article that appeared ed to smear my well-deserved Zombie Whores from An- honorable reputation. I am other Plane! on the front page. In no way did I, or even would I, merciless- not fully aware of all the laws by Mordo Taeil 3 ly kill an innocent person. This of the land, but I would hope Before the Battle so called story that I in some that this type of slander isn’t by Hammond Eveshear 3 way could lower my morals to permitted, and as such, the local knights will look into the Heroes of Novashan Cure commit such a despicable act situation accordingly and at the Rolanoff Plague! of murdering an entire family, least bring this slime to make a by Zachary Farmer 3 including the children in it, is preposterous. public apology and admission A Call to Arms! of lying. by Sir Derek Crownguard 4 For the past month, as its citi- zens can confirm, I have been In the meantime, I would like Creatures of Mystery residing in the town of Rasp- to call out to any people that by Alerick Von Bremen 5 berry. -

From Jew to Puritan: the Emblematic Owl in Early English Culture

FROM JEW TO PURITAN: THE EMBLEMATIC OWL IN EARLY ENGLISH CULTURE Brett D. Hirsch Puritan in Northamptonshire takes offence to his neighbour’s maypole and threatens to have it taken down, despite the anticipated costs of litigation. AHis neighbour is understandably taken aback by this confrontation, and after questioning the Puritan’s authority in the matter, takes his leave and returns to his home. He emerges soon after with an owl on his arm. Turning to the Puritan, he asks him to identify the bird he is holding: ‘An owl,’ is the response. ‘No,’ says the man, ‘’tis a Roundhead on my fist, I hope I may call my Bird what I list.’ The Puritan, fuming at this insult, brings his case before a Justice, who recog- nizes a man’s right to name his pets and dismisses the claim. This is the plot of My Bird is a Round-head, a broadside ballad printed in 1642, the infamous year in which the Puritan parliament succeeded in closing down the London theatres.1 The ballad, which features a custom woodcut depicting the man holding his owl next to the offending maypole (Figure 6), juxtaposes one Round- head against another: a Roundhead in the political sense (so named because of the distinctive haircut worn by the Puritan faction of parliament), and an owl, the only bird with its eyes on the front of its (round) face. The feathered Roundhead is shown to be ‘a gallant Bird’ (13. 5) that, unlike its Puritan namesake, ‘hurteth none’ (8. 5) and meddles not with State affaires, Or sets her neighbours by the eares, I wish to thank Anne and Chris Wortham, Gabriel Egan, David Scott Kastan, and Bruce Boehrer for their insightful comments and suggestions. -

The Owl, Vol. 7, No. 3 Santa Clara University Student Body

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons The Owl SCU Publications 4-1873 The Owl, vol. 7, no. 3 Santa Clara University student body Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/owl Part of the Fiction Commons, Nonfiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Santa Clara University student body, "The Owl, vol. 7, no. 3" (1873). The Owl. Book 32. http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/owl/32 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SCU Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Owl by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~D,t~ ~IQl~01· ~@~l~l~e SANTA CLARA, CAI/. Under the ,Management of the Society of Jesns, ~arg~ n-: now the st DUmbel' of Professors and Tn tors connected with any educational institution on the Paciflc Coast. It embraces Schools of . THEOLOGY, PHY~ICS, CLASSICS, PIIILOSOPIIY, ~fATIIE~IATICS, ORATORY, CHE~lISTI{Y,' IvfINERALOGY, LITERATUI~E. 'F RENCI-I, GERl\IAN, ITALIAN, SPANISlf (By Teachers na tive to the several languages) ~tcttitcct\tt'nt, ~ittt'h~utit.1tt, ~l\u.(l~tltl)t lttut ~igtu·t ~l'lU\!hltl, MVll[e~ V"AL AN. INSTK,UJlBNTA.L, l)ANOING; DIlA.1fATIO ..ciCTION AND DELlvTEI{Y. ~ILIT.A:R-Y DRILL:7 Practical Schools of Telegraphy, Photography, Surveying and Printing; daily Assays of native ores, in a thoronghly fitted laboratory; one of the most complete cabinets of apparatus in the United States; several Ilbrarice ; a brass band; the fullest 'collection of printed music possessed 'by any American College. -

Pumpkin Variety Performance with and Without Treatment for Powdery Mildew in Northern Indiana, 2017

Midwest Vegetable Trial Report for 2017 Pumpkin Variety Performance With and Without Treatment for Powdery Mildew in Northern Indiana, 2017 Elizabeth T. Maynard and Erin A. Bluhm, Purdue University PO Box 1759, Valparaiso, IN 46384 [email protected] Introduction Pumpkins are grown on 5,000 acres in Indiana with an average yield of 6.75 tons per acre. In 2016 the value of Indiana's utilized production was $9.5 million (USDA NASS, 2017a). Successful pumpkin production requires the use of varieties that yield well and produce pumpkins of the size, shape, color, and quality demanded by the market. Genetic resistance to the fungal disease powdery mildew is present in some varieties. This trial was designed to evaluate performance of pumpkin varieties in northern Indiana with and without treatment for powdery mildew. The trial included fourteen orange jack-o-lantern size pumpkins, one small or 'pie' pumpkin and one specialty yellow pumpkin. Materials and Methods A replicated trial was conducted at the Pinney-Purdue Agricultural Center in Wanatah, Indiana. Treatments were arranged in a split plot design with powdery mildew treatment (yes or no) as the main plot, and variety as the sub-plot. Treatments were replicated two times in blocks. For powdery mildew treatment, the experimental unit was 30 ft. by 360 ft. and contained 16 sub- plots, one per variety. Four such units comprised the experiment and were separated by three 15- ft. alleys. Each variety sub-plot had two 30-ft. rows of one variety. The two rows were 7.5 ft. apart. The distance between rows of different varieties was 15 ft., thus each variety was centered in a plot 22.5 ft.