Antidepressants, Other Therapeutic Class Review (TCR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Your Symptom Diary

MEDICATION GUIDE FETZIMA® (fet-ZEE-muh) (levomilnacipran) extended-release capsules, for oral use What is the most important information I should know about FETZIMA? FETZIMA may cause serious side effects, including: • Increased risk of suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, adolescents, and young adults. FETZIMA and other antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children and young adults, especially within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed. FETZIMA is not for use in children. o Depression or other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal thoughts or actions. Some people may have a higher risk of having suicidal thoughts or actions. These include people who have (or have a family history of) depression, bipolar illness (also called manic-depressive illness) or have a history of suicidal thoughts or actions. How can I watch for and try to prevent suicidal thoughts and actions? o Pay close attention to any changes, especially sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, or feelings, or if you develop suicidal thoughts or actions. This is very important when an antidepressant medicine is started or when the dose is changed. o Call your healthcare provider right away to report new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, or feelings. o Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider as scheduled. Call your healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you have concerns about symptoms. Call your healthcare provider or -

624.Full.Pdf

1521-009X/44/5/624–633$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/dmd.115.068932 DRUG METABOLISM AND DISPOSITION Drug Metab Dispos 44:624–633, May 2016 Copyright ª 2016 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Development of a Rat Plasma and Brain Extracellular Fluid Pharmacokinetic Model for Bupropion and Hydroxybupropion Based on Microdialysis Sampling, and Application to Predict Human Brain Concentrations Thomas I.F.H. Cremers, Gunnar Flik, Joost H.A. Folgering, Hans Rollema, and Robert E. Stratford, Jr. Brains On-Line BV, Groningen, The Netherlands (T.I.F.H.C., G.F. J.H.A.F.); Rollema Biomedical Consulting, Mystic, Connecticut (H.R.); and Division of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Mylan School of Pharmacy, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (R.E.S.) Received December 11, 2015; accepted February 24, 2016 Downloaded from ABSTRACT Administration of bupropion [(6)-2-(tert-butylamino)-1-(3-chlorophenyl) concentration ratio at early time points was observed with propan-1-one] and its preformed active metabolite, hydroxybupropion bupropion; this was modeled as a time-dependent uptake clear- [(6)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)-2-[(1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-propanyl)amino]- ance of the drug across the blood–brain barrier. Translation of the 1-propanone], to rats with measurement of unbound concentrations model was used to predict bupropion and hydroxybupropion dmd.aspetjournals.org by quantitative microdialysis sampling of plasma and brain extra- exposure in human brain extracellular fluid after twice-daily cellular fluid was used to develop a compartmental pharmacoki- administration of 150 mg bupropion. Predicted concentrations netics model to describe the blood–brain barrier transport of both indicate that preferential inhibition of the dopamine and norepi- substances. -

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima®) Indication

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima®) Indication: Indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), FDA approved July 2013. Mechanism of action Levomilnacipran, the more active enantiomer of racemic milnacipran, is a selective SNRI with greater potency for inhibition of norepinephrine relative to serotonin reuptake Compared with duloxetine or venlafaxine, levomilnacipran has over 10-fold higher selectivity for norepinephrine relative to serotonin reuptake inhibition The exact mechanism of the antidepressant action of levomilnacipran is unknown Dosage and administration Initial: 20 mg once daily for 2 days and then increased to 40 mg once daily. The dosage can be increased by increments of 40 mg at intervals of two or more days Maintenance: 40-120 mg once daily with or without food. Fetzima should be swallowed whole (capsule should not be opened or crushed) Levomilnacipran and its metabolites are eliminated primarily by renal excretion o Renal impairment Dosing: Clcr 30-59 mL/minute: 80 mg once daily Clcr 15-29 mL/minute: 40 mg once daily End-stage renal disease (ESRD): Not recommended Discontinuing treatment: Gradually taper dose, if intolerable withdrawal symptoms occur, consider resuming the previous dose and/or decrease dose at a more gradual rate How supplied: Capsule ER 24 Hour Fetzima Titration: 20 & 40 mg (28 ea) Fetzima: 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, 120 mg Warnings and Precautions Elevated Blood Pressure and Heart Rate: measure heart rate and blood pressure prior to initiating treatment and periodically throughout treatment Narrow-angle glaucoma: may cause mydriasis. Use caution in patients with controlled narrow- angle glaucoma Urinary hesitancy or retention: advise patient to report symptoms of urinary difficulty Discontinuation Syndrome Seizure disorders: Use caution with a previous seizure disorder (not systematically evaluated) Risk of Serotonin syndrome when taken alone or co-administered with other serotonergic agents (including triptans, tricyclics, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, and St. -

Levomilnacipran for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

Out of the Pipeline Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder Matthew Macaluso, DO, Hala Kazanchi, MD, and Vikram Malhotra, MD An SNRI with n July 2013, the FDA approved levomil- Table 1 once-daily dosing, nacipran for the treatment of major de- Levomilnacipran: Fast facts levomilnacipran pressive disorder (MDD) in adults.1 It is I Brand name: Fetzima decreased core available in a once-daily, extended-release formulation (Table 1).1 The drug is the fifth Class: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake symptoms of inhibitor serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibi- MDD and was well Indication: Treatment of major depressive tor (SNRI) to be sold in the United States disorder in adults tolerated in clinical and the fourth to receive FDA approval for FDA approval date: July 26, 2013 trials treating MDD. Availability date: Fourth quarter of 2013 Levomilnacipran is believed to be the Manufacturer: Forest Pharmaceuticals more active enantiomer of milnacipran, Dosage forms: Extended–release capsules in which has been available in Europe for 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg strengths years and was approved by the FDA in Recommended dosage: 40 mg to 120 mg 2009 for treating fibromyalgia. Efficacy of capsule once daily with or without food levomilnacipran for treating patients with Source: Reference 1 MDD was established in three 8-week ran- domized controlled trials (RCTs).1 cial and occupational functioning in addi- Clinical implications tion to improvement in the core symptoms Levomilnacipran is indicated for treating of depression.5 -

Premium Non-Specialty Quantity Limit List January 2016

Premium Non-Specialty Quantity Limit List January 2016 Therapeutic Category Drug Name Dispensing Limit Anti-infectives Antibiotics DIFICID (fidaxomicin) 200 mg 2 tabs/day & 10 days/30 days SIVEXTRO (tedizolid) Solr 6 vials/30 days SIVEXTRO (tedizolid) Tabs 6 tabs/30 days ZYVOX (linezolid) 28 tabs/30 days ZYVOX (linezolid) Suspension 4 bottles (600 mL)/28 days Antifungals LAMISIL (terbinafine) 250 mg 84 days supply/180 days Antimalarial QUALAQUIN (quinine) QL varies* Antivirals, Herpetic FAMVIR (famciclovir) 125 mg 1 tab/day FAMVIR (famciclovir) 250 mg 2 tabs/day FAMVIR (famciclovir) 500 mg 21 tabs/30 days SITAVIG (acyclovir) 50 mg 2 tabs/30 days VALTREX (valacyclovir) 1000 mg 3 tabs/day VALTREX (valacyclovir) 500 mg 2 tabs/day Antivirals, Influenza RELENZA (zanamivir) QL is 40 inh per 365 days. TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) 30 mg 40 caps per 365 days TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) 45 mg, 75 mg 20 caps per 365 days TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) Suspension 360 mL/365 days Cardiology Anticoagulants ELIQUIS (apixiban) 2 tabs/day ELIQUIS (apixiban) 5 mg 3 tabs/day IPRIVASK (desirudin) 35 days supply/180 days PRADAXA (dabigatran) 2 caps/day SAVAYSA (edoxaban) 1 tab/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 10 mg 35 days supply/180 days XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 15 mg 2 tabs/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 20 mg 1 tab/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) Starter Pack 2 starter packs/year Heart Failure CORLANOR (ivabradine) 2 tabs/day Central Nervous System ADHD Agents ADDERALL (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine) 3 tabs/day ADDERALL XR (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine mixed salts) 1 cap/day APTENSIO XR (methylphenidate) -

Pristiq (Desvenlafaxine Succinate) – First-Time Generic

Pristiq® (desvenlafaxine succinate) – First-time generic • On March 1, 2017, Teva launched AB-rated generic versions of Pfizer’s Pristiq (desvenlafaxine succinate) 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg extended-release tablets for the treatment of major depressive disorder. — Teva launched the 25 mg tablet with 180-day exclusivity. — In addition, Alembic/Breckenridge, Mylan, and West-Ward have launched AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg extended-release tablets. — Greenstone’s launch plans for authorized generic versions of Pristiq 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg tablets are pending. — Lupin and Sandoz received FDA approval of AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg tablets on June 29, 2015. Lupin’s and Sandoz’s launch plans are pending. • Other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder include desvenlafaxine fumarate, duloxetine, Fetzima™ (levomilnacipran), Khedezla™ (desvenlafaxine) , venlafaxine, and venlafaxine extended-release. • Pristiq and the other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors carry a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. • According to IMS Health data, the U.S. sales of Pristiq were approximately $883 million for the 12 months ending on December 31, 2016. optumrx.com OptumRx® specializes in the delivery, clinical management and affordability of prescription medications and consumer health products. We are an Optum® company — a leading provider of integrated health services. Learn more at optum.com. All Optum® trademarks and logos are owned by Optum, Inc. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered marks of their respective owners. This document contains information that is considered proprietary to OptumRx and should not be reproduced without the express written consent of OptumRx. -

T.C. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Bazi Antidepresan Ilaç Numunelerinin Pcr Ve Pls

T.C. SÜLEYMAN DEMİREL ÜNİVERSİTESİ FEN BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ BAZI ANTİDEPRESAN İLAÇ NUMUNELERİNİN PCR VE PLS İLE SPEKTROFOTOMETRİK TAYİNLERİ Nuray AYTEKİN Danışman Prof. Dr. Ahmet Hakan AKTAŞ YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ KİMYA ANABİLİM DALI ISPARTA - 2014 2 © 2014 [Nuray AYTEKİN] TAAHHÜTNAME Bu tezin akademik ve etik kurallara uygun olarak yazıldığını ve kullanılan tüm literatür bilgilerinin referans gösterilerek tezde yer aldığını beyan ederim. Nuray AYTEKİN ii İÇİNDEKİLER Sayfa İÇİNDEKİLER ......................................................................................................................... i ÖZET ......................................................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. iv TEŞEKKÜR .............................................................................................................................. v ŞEKİLLER DİZİNİ ................................................................................................................. vi ÇİZELGELER DİZİNİ ............................................................................................................ vii SİMGELER VE KISALTMALAR DİZİNİ .......................................................................... viii 1. GİRİŞ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Sertralinenin -

WO 2012/068516 A2 24 May 20 12 (24.05.2012) W P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/068516 A2 24 May 20 12 (24.05.2012) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (72) Inventors; and A61K 31/352 (2006.01) A61P 25/24 (2006.01) (75) Inventors/Applicants (for US only): LETENDRE, Peter A61K 9/48 (2006.01) A61P 25/22 (2006.01) [US/US]; 2389 Indian Peaks Trail, Lafayette, Colorado A61K 9/20 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) 80026 (US). CARLEY, David [US/US]; 2457 Pioneer Rd., Evanston, Illinois 60201 (US). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US201 1/061490 (74) Agents: FEDDE, Kenton et al; 18325 AUenton Woods Ct, Wildwood, Missouri 63069 (US). (22) International Filing Date: 18 November 201 1 (18.1 1.201 1) (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (25) Language: English Filing AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (26) Publication Language: English CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (30) Priority Data: HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, 61/415,33 1 18 November 2010 (18. 11.2010) US KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): PIER MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PHARMACEUTICALS [US/US]; 901 Front St., Suite OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, 201, Louisville, Colorado 80027 (US). -

A Brief Overview of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy

A Brief Overview of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Joel V. Oberstar, M.D. Chief Executive Officer Disclosures • Some medications discussed are not approved by the FDA for use in the population discussed/described. • Some medications discussed are not approved by the FDA for use in the manner discussed/described. • Co-Owner: – PrairieCare and PrairieCare Medical Group – Catch LLC Disclaimer The contents of this handout are for informational purposes only and are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or psychiatric condition. Never disregard professional/medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this handout. Material in this handout may be copyrighted by the author or by third parties; reasonable efforts have been made to give attribution where appropriate. Caveat Regarding the Role of Medication… Neuroscience Overview Mind Over Matter, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://teens.drugabuse.gov/mom/index.asp. http://medicineworld.org/images/news-blogs/brain-700997.jpg Neuroscience Overview Mind Over Matter, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://teens.drugabuse.gov/mom/index.asp. Neurotransmitter Receptor Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse Common Diagnoses and Associated Medications • Psychotic Disorders – Antipsychotics • Bipolar Disorders – Mood Stabilizers, Antipsychotics, & Antidepressants • Depressive Disorders – Antidepressants • Anxiety Disorders – Antidepressants & Anxiolytics • Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – Stimulants, Antidepressants, 2-Adrenergic Agents, & Strattera Classes of Medications • Anti-depressants • Stimulants and non-stimulant alternatives • Anti-psychotics (a.k.a. -

Desvenlafaxine

https://providers.amerigroup.com CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL PATIENT INFORMATION desvenlafaxine Prior Authorization of Benefits (PAB) Form Complete form in its entirety and fax to: Prior Authorization of Benefits Center at 1-844-512-9004 Provider Help Desk 1-800-454-3730 1. PATIENT INFORMATION 2. PHYSICIAN INFORMATION Patient Name: Prescribing Physician: Patient ID #: Physician Address: Patient DOB: Physician Phone #: Date of Rx: Physician Fax #: Patient Phone #: Physician Specialty: Patient Email Address: Physician DEA: Physician NPI #: Physician Email Address: 3. MEDICATION 4. STRENGTH 5. DIRECTIONS 6. QUANTITY PER 30 DAYS desvenlafaxine Specify: 7. DIAGNOSIS: 8. APPROVAL CRITERIA: CHECK ALL BOXES THAT APPLY NOTE: Any areas not filled out are considered not applicable to your patient & MAY AFFECT THE OUTCOME of this request. □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with two preferred generic SSRIs* has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these agents would be medically contraindicated □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with one preferred generic SNRI** has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these agents would be medically contraindicated □ Yes □ No Documentation of a previous trial and therapy failure at a therapeutic dose with one non-SSRI/SNRI generic antidepressant** has been provided If No: □ Yes □ No Documented evidence is provided that the use of these -

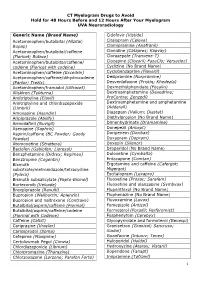

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson's Disease

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Parkinson’s Disease Volume 2015, Article ID 609428, 71 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/609428 Review Article Monoamine Reuptake Inhibitors in Parkinson’s Disease Philippe Huot,1,2,3 Susan H. Fox,1,2 and Jonathan M. Brotchie1 1 Toronto Western Research Institute, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, 399 Bathurst Street, Toronto, ON, Canada M5T 2S8 2Division of Neurology, Movement Disorder Clinic, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, 399BathurstStreet,Toronto,ON,CanadaM5T2S8 3Department of Pharmacology and Division of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, UniversitedeMontr´ eal´ and Centre Hospitalier de l’UniversitedeMontr´ eal,´ Montreal,´ QC, Canada Correspondence should be addressed to Jonathan M. Brotchie; [email protected] Received 19 September 2014; Accepted 26 December 2014 Academic Editor: Maral M. Mouradian Copyright © 2015 Philippe Huot et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease (PD) are secondary to a dopamine deficiency in the striatum. However, the degenerative process in PD is not limited to the dopaminergic system and also affects serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons. Because they can increase monoamine levels throughout the brain, monoamine reuptake inhibitors (MAUIs) represent potential therapeutic agents in PD. However, they are seldom used in clinical practice other than as antidepressants and wake-promoting agents. This review article summarises all of the available literature on use of 50 MAUIs in PD. The compounds are divided according to their relative potency for each of the monoamine transporters.