IDEALS @ Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

72 Jaargang Nr. 4 KONTAKT Januari 2010

BSG 72e jaargang nr. 4 KONTAKT januari 2010 Periodiek van het Bussums Schaakgenootschap Clublokaal Clubavond Denksportcentrum, Nieuwe Englaan 6 Jeugd: vrijdag 19.00-20.15 uur 1404 EC Bussum, 035-6936471 Senioren: maandag 19.30-24.00 uur Contact Contributie www.bsg-bussum.nl Senioren €110,- Jeugdleden €65,- [email protected] Girorekening 364268 Vice voorzitter: Tom Fikkert Theresiahof 48, 1216 MK Hil‟sum Voorzitter: Rob Disselhoff [email protected] Moerbeiboom 39 4101 WC Culemborg 035-6238429 [email protected] 0345-519696 Penningmeester:Eddy v.d. Velden Cereslaan 32, 1402 LL Bussum Secretaris+ledenadmin: Lennart Ootes [email protected] A.Fokkersingel 32, 2497 BG Den Haag 035-6980689 [email protected] 06-47828789 Algemeen lid: Theo Slisser Tjalk 20, 1276 EB Huizen Projectleider jubileum: Edwin Baart [email protected] Gen. de la Reijln 14b,1404 BS Bussum 035 - 5256543 06-10188106 [email protected] 035-6942078 Redacteur: Bert Kieboom Blijklaan 14, 1394 KB N‟den Berg Intern wedstrijdleider + algemeen lid: [email protected] Rik Weidema 0294-257153 Kon.Julianastr 14, 1271 SM Huizen [email protected] Distributeur: Wim Roeten 035-5269230 De Berken 64, 1402 KS Bussum 035-6910174 Eindredacteur: Melchior Brandenburg K.Onnesweg 285, 1223 JJ Hilversum Co. extern comp:Sicco Reeskamp [email protected] Verl. Fortlaan 25, 1412 CW Bussum 035-6837510 [email protected] 06-2222281 Januari 2010 1 Kontakt Inhoudsopgave Colofon . 1 Inhoudsopgave . 2 Kopij data 2009 - 2010. .. 2 Van de redactie . 3 Seizoensplanning 2009 - 2010 . 4 Van het bestuur . 6 Vermetel schaakspel. 7 BSG scoort Royal Flush tegen AAS . 8 BSG 3 start 2010 met zevenklapper. -

December 2018 45

løst og fast omkring Skørping Skakklub December 2018 45. årgang nr. 2 Ulf Andersson – William Hartston Sort trækker Spillet i Nytårsturneringen i Hastings 1972/73. Løsning side 9 Top 20 Pokalturneringen Slutspilsteknik m.m. Årets højdespringer er fundet Lidt indføring i netskak med Lars Jørgensen 1 Få forskydninger – men én markant – på Top 20 I sagens natur sker der ikke de helt store omvæltninger i rækkefølgen, når Skørping Skakklubs årlige opgørelse over ”Alle tiders Top 20” (nu ”Top 24”) finder sted. Sæsonen 2017 – 2018 (altså ikke den aktuelle) bød dog på avancement til hele 2 spillere, nemlig Peter Mikkelsen som via klubmesterskab og pokalvinder (altså ”The Double” til Norup/Øster Hurup) lagde hele 6 points på sin konto og røg op som nummer 4, mens Johannes Struijk, som vandt sølv både i efteråret 2017 og 2018, ifølge ”reglementet” for Top 20 scorede et enkelt point, som bragte ham fra 5 til 6 på listen, hvor han nu indtager en placering som nr. 16. Hele listen ser således ud: Plads Spiller Points Førstepladser 01. Niels Chr. Davidsen 146 38 02. Arne Søgaard 81 17 03. Hans Andersen 58 11 04. Peter Mikkelsen 40 9 05. Anker Nielsen 35 7 06. Regnar Simonsen 29 5 07. Arne Christensen 20 3 08. Niels Søgaard Jakobsen 19 6 09. Jens Thygesen 18 4 10. Arne Valsted 15 4 11. Poul Erik Hyldgaard Jensen 11 3 12. Søren Hauge 11 3 13. John Steffensen 10 2 14. Knud Erik Jensen 9 3 15. Steffen Slumstrup Nielsen 7 2 16. Johannes Struijk 6 1 17. Sven Erik Østergaard 5 1 18. -

Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers: Bridging Research and Practice

Upjohn Press Upjohn Research home page 8-28-2009 Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers: Bridging Research and Practice Maude Toussaint-Comeau University of Illinois at Chicago Bruce D. Meyer University of Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/up_press Part of the Income Distribution Commons, and the Labor Economics Commons Citation Toussaint-Comeau, Maude, and Bruce D. Meyer, eds. 2009. Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers: Bridging Research and Practice. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. https://doi.org/10.17848/9781441631992 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers Strategies for Improving Economic Mobility of Workers Bridging Research and Practice Maude Toussaint-Comeau Bruce D. Meyer Editors 2009 W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Kalamazoo, Michigan Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Strategies for improving economic mobility of workers : bridging research and practice / Maude Toussaint-Comeau and Bruce D. Meyer, editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-88099-352-4 (pbk : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-88099-352-9 (pbk : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-88099-353-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-88099-353-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Migration, Internal—United States. 2. Occupational retraining—United States. 3. Housing subsidies—United States. I. Toussaint-Comeau, Maude. II. Meyer, Bruce D. HB1965.S76 2009 331.12'70973—dc22 2009022482 © 2009 W.E. -

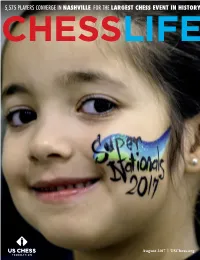

Chess Life: to Receive Chess Life As a Premium Member, Join US Chess Or Enter a US Chess Tournament, Go to Uschess.Org Or Call 1-800-903-USCF (8723)

5,575 PLAYERS CONVERGE IN NASHVILLE FOR THE LARGEST CHESS EVENT IN HISTORY August 2017 | USChess.org The Uniteed States’ Largest Chess Sppecialty Retailer '''%! %!"$#&& Wild SSttyle BooaINTRaardsRODUCING THE NEW EXCITING FULL COLOR VINYL CHESS BOARDS EMOJI WILD HORSES FIRREFIGHTER RAINBOW CATCH THE WAVE FLAG OF USA SPLATTTERED PAINTA GOLDEN GATE CRYSTALA DRREAMS 8 BIT HHEAVEN PUNK ARMY OVER 80 DESIGNS AT GM Viswanathan ANAND GM Hikaru NAKAMURA GM Levon ARONIAN GM Ian NEPOMNIACHTCHI GM Magnus CARLSEN GM Wesley SO GM Fabiano CARUANA GM Peter SVIDLER GM Sergey KARJAKIN GM Maxime VACHIER-LAGRAVE TUESDAY AUGUST 1 TBA Autograph Session 6 PM Opening Ceremony WEDNESDAY AUGUST 2 1 PM Round 1 THURSDAY AUGUST 3 1 PM Round 2 FRIDAY AUGUST 4 1 PM Round 3 SATURDAY AUGUST 5 1 PM Round 4 SUNDAY AUGUST 6 1 PM Round 5 MONDAY AUGUST 7 — Rest Day TUESDAY AUGUST 8 1 PM Round 6 WEDNESDAY AUGUST 9 1 PM Round 7 THURSDAY AUGUST 10 1 PM Round 8 FRIDAY AUGUST 11 1 PM Round 9 AUGUST 2-12 SATURDAY AUGUST 12 1 PM (if necessary) #GRANDCHESSTOUR #SINQUEFIELDCUP 6 PM Closing Ceremony GM Viswanathan ANAND GM Garry KASPAROV GM Levon ARONIAN GM Le Quang LIEM GM Fabiano CARUANA GM Hikaru NAKAMURA GM Lenier DOMINGUEZ GM Ian NEPOMNIACHTCHI GM Sergey KARJAKIN GM Wei YI SUNDAY AUGUST 13 6 PM Opening Ceremony MONDAY AUGUST 14 1 PM Rapid Rounds 1-3 TUESDAY AUGUST 15 1 PM Rapid Rounds 4-6 WEDNESDAY AUGUST 16 1 PM Rapid Rounds 7-9 THURSDAY AUGUST 17 1 PM Blitz Rounds 1-9 FRIDAY AUGUST 18 1 PM Blitz Rounds 10-18 SATURDAY AUGUST 19 1 PM (if necessary) TBA Ultimate Moves AUGUST 14-19 6 PM Closing Ceremony #GRANDCHESSTOUR #STLRAPIDBLITZ WATCH LIVE ON GRANDCHESSTOUR.ORG ROUNDS DAILY AT 1 P.M. -

APPENDIX B: State, Local, and Federal Laws Barring Source-Of-Income Discrimination

Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program APPENDIX B: State, Local, and Federal Laws Barring Source-of-Income Discrimination Updated August 2021 Set out below is a compilation of state, local, and federal statutes prohibiting discrimination in the housing market based on source of income, along with an annotated bibliography of studies and published articles relating to discrimination against families with federal Housing Choice Vouchers. You can use the hyperlinks in the table of contents to navigate through the document. This compilation updates research originally compiled by PRRAC in 2009 and also drawing on earlier documents prepared by the National Housing Law Project and the Center for Policy Alternatives. The compilation was updated for the Fourth National Housing Mobility Conference in 2012 and was published as an appendix to the PRRAC- Urban Institute housing mobility toolkit that followed the conference, Expanding Choice: Practical Strategies for Building a Successful Housing Mobility Program (February 2013). Since 2013, we have regularly updated the appendix as these state and local laws have proliferated. In addition, we have compiled a guide for advocates and local policy leaders, titled Crafting an Effective Local Source of Income Discrimination Law (March 2020). In 2018, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities released a report using the data from this Appendix to provide a national overview of laws protecting Housing Choice Voucher families from discrimination. The report, Prohibiting Discrimination Against Renters Using Housing Vouchers Improves Results, by Alison Bell, Barbara Sard, and Becky Koepnick (December 2018), includes a chronology of adoption of the statutes and ordinances described below, and an interactive map.1 In 2020, the Urban Institute also developed a dataset based on this Appendix, which presents the information in a more analytic framework, including scoring of the relative strength of the laws. -

October 2020 Northwest Chess October 2020, Volume 74-10 Issue 873 on the Front Cover: ISSN Publication 0146-6941 See Game Page Nine

orthwes $3.95 N t C h e s s October 2020 Northwest Chess October 2020, Volume 74-10 Issue 873 On the front cover: ISSN Publication 0146-6941 See game page nine. Photo credit: Philip Peterson. Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. To see the games online in this issue click: http://www.nwchess.com/articles/games/published/ published_games.htm POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: On the back cover: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Another view. Photo credit: Philip Peterson. Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Submissions Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), [email protected] stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please [email protected] indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: Board Representatives Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Chouchanik Airapetian, Eric Holcomb, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Alex Machin, Duane Polich, Ralph Dubisch, Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 Jeffrey Roland, Josh Sinanan. or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2020 by Northwest Chess. All rights reserved. [email protected] Published opinions are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editor or the Northwest Chess Northwest Chess Knights Board. -

ICCA RECOMMENDED LICHESS PREFERENCES the Following

ICCA RECOMMENDED LICHESS PREFERENCES The following preference settings are recommended by the ICCA (and may be required by some tournaments or conferences). All SUGGESTED and RECOMMENDED settings are based on the idea of creating an experience as close to Over-The-Board (OTB) chess as possible. Preference settings can be enforced by looking at the gameplay history which records not only the moves, but the player and clock behavior throughout the game. ICCA recommended settings are bolded and underlined. • SUGGESTED means that this setting does not impact the gameplay experience and is just a suggested setting. • RECOMMENDED means that these are closer to requirements; these settings ensure that no extra benefit to players from them using an online format. RATED VS. UNRATED GAMES • The ICCA recommends that all official games be played as RATED. Unrated games do not take advantage of the website’s full cheat detection, so having all official games played as rated ensures that we are encouraging the most cheat detection possible. GAME DISPLAY SETTINGS Suggested v Setting Options Explanation Recommended None This setting determines how quickly a piece will appear to move once a move Fast Piece Animation has been selected. It may impact the speed of gameplay, but any setting here SUGGESTED Normal will be fine; the ICCA suggests using “None” or “Fast” Slow In OTB chess, we would see all captured pieces, not just the material No Material Difference difference, however, LiChess has no option to display all captured pieces, so in SUGGESTED Yes this case, it’s a matter of personal preference. This feature highlights the last move made and indicates if Check is on board. -

Chess As a Commodity?

Debate Chess as a commodity? 10 Aug 2020 Four and a half months have gone by with hardly any significant classical chess. Elite players have started to behave like hustlers. One of the most hyped chess competitions ever was staged between beginners. Raj Tischbierek asks if it is an irreversible development or just a nightmare that will pass. A dream One of those hot, sweaty June nights catapults me back to the year 1970. I am in the Yugoslavian town of Herceg Novi reporting for my magazine from the strongest blitz tournament in chess history until then. Bobby Fischer dominates the competition at will. The fight for second place is more exciting, between the four Soviets Mikhail Tal, Viktor Korchnoi, Tigran Petrosian and David Bronstein. In the last round Tal has gained substantial ground: in an endgame of rook versus rook he flags Petrosian! The Yugoslav commentators discuss with him the subtleties of this tricky endgame, which, I learn, is being played by the young Anatoly Karpov with masterful precision. Tal thus got ahead of Korchnoi, who tried his utmost against the American veteran Samuel Reshevsky. He didn’t simply resign what seemed to me a hopeless endgame, but let his clock run down almost to the last seconds. In vain: unlike in some earlier rounds, Sammy did not fall off the table from exhaustion and Korchnoi had to accept a bitter defeat. Among the lapwings I spot FIDE-President Folke Rogard: “How do you like the tournament?” – “Great! The response is overwhelming! In the next room, a television set is showing a football match between Yugoslavia and Austria. -

Caïssa Magazine #10

Caïssa Magazine #10 EDITO JANVIER 2021 En ce début d’année 2021, l’heure est aux vœux et toute l’équipe de la DNEF vous adresse les siens pour cette année qui débute ! Vœux de bonne santé en priorité, de dynamisme, de bonnes résolutions, d’espoir, de réussite échiquéenne, de joie partagée en famille et dans la pratique de notre sport ! Nous avons, toutes et tous, hâte de nous retrouver devant un échiquier ! L’heure est également au bilan de l’année difficile qui vient de s’achever. Cette crise ne nous a pas épargnés en rendant difficile la pratique de notre sport et en nous privant de vraies rencontres dans les clubs. Cependant, la DNEF de la FFE a su, dès le début du printemps, s’adapter à la situation et trouver des solutions permettant aux joueuses de participer à des tournois de différents formats. Près de 90 tournois amicaux ont été organisés, ainsi que des matchs entre championnes et des compétitions internationales, qui ont permis de réunir l’élite féminine française et de nombreuses passionnées ! Un grand merci à toutes les personnes qui nous ont soutenues dans ces projets ! La DNEF s’est également renforcée depuis peu, grâce à l’arrivée de la joueuse professionnelle, Silvia Alexieva GMF et MI. Enfin, l’année s’est achevée avec la dernière grande compétition féminine, la 19ème édition du Trophée Roza Lallemand et première en ligne, qui a rencontré un véritable succès avec 234 participantes ! Félicitations à Cécile Haussernot qui a décroché le titre national en parties rapides ! Tous ces évènements ont permis de susciter un nouvel engouement auprès du public féminin. -

Military Guidebook

National Forwarding Co., Inc. Military Guidebook 11/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS National Forwarding Co., Inc. – Military Guidebook Visit our Website National Forwarding Directory National Forwarding Compensation Schedule Quick Check List Tab National Forwarding & Affiliates Quick Check List National Forwarding & NVL Driver Quick Check List NFC 409 Network Drivers Quick Check List Distribution of Documents – 400NG/DP3 Shipments Forwarding of Base Paperwork to NFC CSS Tab Customer Satisfaction Survey Questions Watch List Shipments How Can You Get High Customer Satisfaction Scores? Procedures Tab Pre-Move Survey NFC Pre-Move Survey Form Third Party at Origin Professional Books, Papers & Equipment (Pro-Gear) & Estimate Sheet Front Load Washer Policy Watching for Mold Mattresses and Box Springs Parts, Hardware & Customer Satisfaction High Value/High Risk Policy Firearms Handling and Control Unpacking, Assembly & Debris Removal Uncrating VS Unpacking Weights & Inventories Tab Proper Military Inventory Procedures Properly Completed Inventory Proper Weighing Procedures Reweigh Requests DTR – Defense Transportation Regulations Tab Military Installation Map Appendix B – TOS – Tender of Service Chapter 405 – Quality Assurance (QA) “It’s Your Move” – Customer’s Allowances and Responsibilities Visit our website: www.nationalforwarding.com You will find updates about • NFC • Tonnage Lists • Agent Memos • DOD Personal Property Program 10/19/2017 NATIONAL FORWARDING DIRECTORY ADMINISTRATION & BILLING: OPERATIONS: CLAIMS: PH: 708-345-0550 PH: 800-722-9144 PH: 800-325-6889 PH: 800-323-9125 FX: 708-345-0554 FX: 708-345-5218 FX: 708-345-3245 MOVE MANAGEMENT: INTERNATIONAL: AGENCY SERVICES: PH: 888-993-6683 PH: 800-323-1963 PH: 800-323-9125 FX: 708-356-5220 FX: 708-450-1273 FX: 708-345-9112 AFTER HOURS: 888-993-6683 TONNAGE: www.nationalforwarding.com DEPARTMENTAL EMAIL SPECIFIC TASK EMAIL Operations [email protected] Blackouts [email protected] Move Mgt. -

The Modernized Caro-Kann by Daniel Fernandez

The Modernized Caro-Kann By Daniel Fernandez 1 This book is written for the Black side, though new ideas for White are sugge- sted and old ones occasionally impro- ved. It contains not only the author’s personal take on how to deal with all major White tries after 1.e4 c6, but al- so a range of alternatives for Black- to cater for different types of Caro-Kann player. This repertoire builds on the ex- isting state of theory, taking it in novel, exciting and decidedly modern direc- tions, while not forgetting about the opening’s sound strategic underpin- nings. The Caro-Kann Defence, long renow- GM Daniel Fernandez (born 1995) has ned for being a solid and reliable de- been an active and accomplished play- fence against 1.e4, is undergoing a re- er for several years. He represented his naissance at the moment. In addition nativd Singapore twice at Olympiads to being a mainstay in the repertoires (2010 and 2012) before transferring to of a recent World Champion (Viswana- the English chess federation. There, he than Anand) and a 2018 World Cham- won the national classical titles at U-18 pionship candidate (Ding Liren), it is be- and U-21 levels, and worked to be- ing flooded with new and creative come a Grandmaster while simultane- ideas from a range of other top play- ously studying at Cambridge. The Caro- ers, notably Anand’s Indian Olympiad Kann was instrumental in his quest for teammates Vidit and Adhiban. The that title. Currently, Daniel is known in pawn structures in this opening leave the chess scene not only as a solid considerable room for individual inter- player, but also as a mentor figure to pretation. -

An Historical Perspective Through the Game of Chess

On the Impact of Information Technologies on Society: an Historical Perspective through the Game of Chess Fr´ed´ericProst1 LIG, Universit´ede Grenoble B. P. 53, F-38041 Grenoble, France [email protected] Abstract The game of chess has always been viewed as an iconic representation of intellectual prowess. Since the very beginning of computer science, the challenge of being able to program a computer capable of playing chess and beating humans has been alive and used both as a mark to measure hardware/software progresses and as an ongoing programming challenge leading to numerous discoveries. In the early days of computer science it was a topic for specialists. But as computers were democratized, and the strength of chess engines began to increase, chess players started to appropriate to themselves these new tools. We show how these interactions between the world of chess and information technologies have been herald of broader social impacts of information technologies. The game of chess, and more broadly the world of chess (chess players, literature, computer softwares and websites dedicated to chess, etc.), turns out to be a surprisingly and particularly sharp indicator of the changes induced in our everyday life by the information technologies. Moreover, in the same way that chess is a modelization of war that captures the raw features of strategic thinking, chess world can be seen as small society making the study of the information technologies impact easier to analyze and to grasp. Chess and computer science Alan Turing was born when the Turk automaton was finishing its more than a century long career of illusion1.