Boston Glacier Research Natural Area Was Backdrop for Boston Glacier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Script

Feb rua rg 1968 North Cascades Conservation Council P. 0. Box 156 Un ? ve rs i ty Stat i on Seattle, './n. 98 105 SCRIPT FOR NORTH CASCAOES SLIDE SHOW (75 SI Ides) I ntroduct Ion : The North Cascades fiountatn Range In the State of VJashington Is a great tangled chain of knotted peaks and spires, glaciers and rivers, lakes, forests, and meadov;s, stretching for a 150 miles - roughly from Pt. fiainier National Park north to the Canadian Border, The h undreds of sharp spiring mountain peaks, many of them still unnamed and relatively unexplored, rise from near sea level elevations to seven to ten thousand feet. On the flanks of the mountains are 519 glaciers, in 9 3 square mites of ice - three times as much living ice as in all the rest of the forty-eight states put together. The great river valleys contain the last remnants of the magnificent Pacific Northwest Rain Forest of immense Douglas Fir, cedar, and hemlock. f'oss and ferns carpet the forest floor, and wild• life abounds. The great rivers and thousands of streams and lakes run clear and pure still; the nine thousand foot deep trencli contain• ing 55 mile long Lake Chelan is one of tiie deepest canyons in the world, from lake bottom to mountain top, in 1937 Park Service Study Report declared that the North Cascades, if created into a National Park, would "outrank in scenic quality any existing National Park in the United States and any possibility for such a park." The seven iiiitlion acre area of the North Cascades is almost entirely Fedo rally owned, and managed by the United States Forest Service, an agency of the Department of Agriculture, The Forest Ser• vice operates under the policy of "multiple use", which permits log• ging, mining, grazing, hunting, wt Iderness, and alI forms of recrea• tional use, Hov/e ve r , the 1937 Park Study Report rec ornmen d ed the creation of a three million acre Ice Peaks National Park ombracing all of the great volcanos of the North Cascades and most of the rest of the superlative scenery. -

1968 Mountaineer Outings

The Mountaineer The Mountaineer 1969 Cover Photo: Mount Shuksan, near north boundary North Cascades National Park-Lee Mann Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during June by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111. Clubroom is at 7191h Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. EDITORIAL STAFF: Alice Thorn, editor; Loretta Slat er, Betty Manning. Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, at above address, before Novem ber 1, 1969, for consideration. Photographs should be black and white glossy prints, 5x7, with caption and photographer's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double-spaced and include writer's name, address and phone number. foreword Since the North Cascades National Park was indubi tably the event of this past year, this issue of The Mountaineer attempts to record aspects of that event. Many other magazines and groups have celebrated by now, of course, but hopefully we have managed to avoid total redundancy. Probably there will be few outward signs of the new management in the park this summer. A great deal of thinking and planning is in progress as the Park Serv ice shapes its policies and plans developments. The North Cross-State highway, while accessible by four wheel vehicle, is by no means fully open to the public yet. So, visitors and hikers are unlikely to "see" the changeover to park status right away. But the first articles in this annual reveal both the thinking and work which led to the park, and the think ing which must now be done about how the park is to be used. -

North Cascades National Park I Mcallister Cutthroat Pass A

To Hope, B.C. S ka 40mi 64km gi t R iv er Chilliwack S il Lake v e CHILLIWACK LAKE SKAGIT VALLEY r MANNING - S k a g PROVINCIAL PARK PROVINCIAL PARK i PROVINCIAL PARK t Ross Lake R o a d British Columbia CANADA Washington Hozomeen UNITED STATES S i Hozomeen Mountain le Silver Mount Winthrop s Sil Hoz 8066ft ia ve o Castle Peak 7850ft Lake r m 2459m Cr 8306ft 2393m ee e k e 2532m MOUNT BAKER WILDERNESS Little Jackass n C Mount Spickard re Mountain T B 8979ft r e l e a k i ar R 4387ft Hozomeen Castle Pass 2737m i a e d l r C ou 1337m T r b Lake e t G e k Mount Redoubt lacie 4-wheel-drive k r W c 8969ft conditions east Jack i Ridley Lake Twin a l of this point 2734m P lo w er Point i ry w k Lakes l Joker Mountain e l L re i C ak 7603ft n h e l r C R Tra ee i C i Copper Mountain a e re O l Willow 2317m t r v e le n 7142ft T i R k t F a e S k s o w R Lake a 2177m In d S e r u e o C k h g d e u c r Goat Mountain d i b u i a Hopkins t C h 6890ft R k n c Skagit Peak Pass C 2100m a C rail Desolation Peak w r r T 6800ft li Cre e ave 6102ft er il ek e e Be 2073m 542 p h k Littl 1860m p C o Noo R C ks i n a Silver Fir v k latio k ck c e ee Deso e Ro Cree k r Cr k k l e il e i r B e N a r Trail a C To Glacier r r O T r C Thre O u s T e Fool B (U.S. -

Naturally Appealing: a Scenic Gateway in Washington's North

Naturally Appealing A scenic getaway in Washington’s North Cascades | By Scott Driscoll s o u r h i k i n g g r o u p arrives at the top of Heather Park, about 110 miles northeast of Seattle. Pass in Washington state’s North Cascades, The Park Service is celebrating the park’s we hear several low, guttural grunts. 40th birthday this year, and also the 20th anni- “That’s the sound of my heart after versary of the Washing- ton Park Wilderness seeing a bear,” comments a female hiker. She Act, which designated 94 percent of the park chuckles a trifle nervously, and we all look around. as wilderness. This area’s “majestic Those grunts sound like they’re coming from more mountain scenery, snowfields, glaciers, than one large animal. alpine meadows, lakes and other unique glaci- Whatever’s causing the sound remains well hid- ated features” were cited den behind huckleberries, subalpine firs and boul- as some of the reasons ders, but Libby Mills, our naturalist guide, sets our Congress chose to pro- minds at ease. “Those tect the land in 1968 are male dusky grouse,” “for the benefit, use and she assures us. “They’re inspiration of present competing for female and future generations.” attention.” Those natural fea- She explains that they tures are also among the make the grunting reasons the Park Service sound by inhaling air posted this quote—from CAROLYN WATERS into pink sacs—one at 19th century Scottish each side of the neck— botanist David Douglas, one of the early explorers of and then releasing the the Pacific Northwest and the person for whom the air. -

Wilderness Trip Planner

National Park Service North Cascades National Park Service Complex U.S. Department of the Interior Stephen Mather Wilderness An Enduring Legacy of Wilderness “[I]t is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.” — Wilderness Act, 1964 The North Cascades National Park Complex includes 684,000 acres in three units: North Cascades National Park, Lake Chelan National Recre- ation Area, and Ross Lake National Recreation Area. Congress has designated 94% of the Complex as the Stephen Mather Wilderness. Today, as in the past, wilderness is an important part of every American’s story. People seek out wilderness for a variety of reasons: physical or mental challenge; solitude, renewal, or a respite from modern life; or as a place to find inspiration and to explore our heritage. What draws you to visit wilderness? The Stephen Mather Wilderness is at the heart of over two million acres of some of the wildest lands remaining, a place “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man….” Untrammeled (meaning“free of restraint,” “unconfined”) captures the essence of wilderness: a place where the natural processes of the land prevail, and the developments of modern technological society are substantially unnoticeable. Here, we are visitors, but we also come home—to our natural heritage. It is a place to experience our past, and a place to find future respite. This is the enduring legacy of wilderness. To Hope, B.C. -

Empowering a Generation of Climbers My First Ascent an Epic Climb of Mt

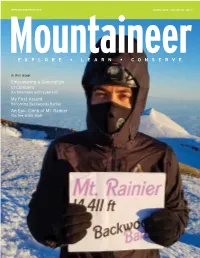

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG SPRING 2018 • VOLUME 112 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE in this issue: Empowering a Generation of Climbers An Interview with Lynn Hill My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall tableofcontents Spring 2018 » Volume 112 » Number 2 Features The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy 24 Empowering a Generation of Climbers the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. An Interview with Lynn Hill 26 My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie 32 An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall Columns 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Marcey Kosman 8 VOICES HEARD 24 1000 Words: The Worth of a Picture 11 PEAK FITNESS Developing a Personal Program 12 BOOKMARKS Fuel Up on Real Food 14 OUTSIDE INSIGHT A Life of Adventure Education 16 YOUTH OUTSIDE We’ve Got Gear for You 18 SECRET RAINIER 26 Goat Island Mountain 20 TRAIL TALK The Trail Less Traveled 22 CONSERVATION CURRENTS Climbers Wanted: Liberty Bell Needs Help 37 IMPACT GIVING Make the Most of Your Mountaineers Donation 38 RETRO REWIND To Everest and Beyond 41 GLOBAL ADVENTURES The Extreme Fishermen of Portugal’s Rota Vicentina 55 LAST WORD Empowerment 32 Discover The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining, or have joined and aren’t sure where to star, why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Mountaineer uses: Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of CLEAR informational meetings at each of our seven branches. on the cover: Bam Mendiola, AKA “Backwoods Barbie” stands on the top of Mount Rainier. -

Sherwood Mine Is in Fluvial Rocks of the Eocene Sanpoil Volcanics (Waggoner, 1990, Geol

Okanogan Tough Nut (434) ALTERNATE NAMES DISTRICT COUNTY Okanogan 0 • PRIMARY QUADRANGLE SCALE 1h x 1° QUAD 1° X 2° QUAD Conconully East 1:24,000 Oroville Okanogan LATITUDE LONGITUDE SECTION, TOWNSHIP, AND RANGE 48° 34' 46.84" N 119° 44' 55.56" w NWl/4 sec. 31, 36N, 25E, elev. 3,200 ft LOCATION: elev. 3,200 ft HOST ROCK: NAME LITHOLOGY AGE metamorphic complex of Conconully schist pre-Jurassic ASSOCIATED IGNEOUS ROCK: DESCRIPTION AGE Conconully pluton Cretaceous COMMODIDES ORE MINERALS NON-ORE MINERALS Ag galena pyrite, quartz Pb chalcopyrite Cu sphalerite Zn DEPOSIT TYPE MINERALIZATION AGE vein Cretaceous? PRODUCTION: Production prior to 1901 was valued at $9,000 (Moen, 1973). TECTONIC SETTING: The Triassic sediments were deposited along an active margin associated with an island arc. The Conconully pluton is a directionless, post-tectonic body that was intruded into a major structural zone (Stoffel, K. L., OGER, 1990, oral commun.). ORE CONTROLS: The quartz vein is in quartz-mica schist is 3-10 ft wide, strikes N25W, and dips 60SW (Moen, 1973, p. 28). GEOLOGIC SETTING: The vein is in quartz-mica schist of the metamorphic complex of Conconully near the contact • with the Conconully pluton of Cretaceous age (Stoffel, 1990, geol. map). COMMENTS: The mine was developed by a 50-ft inclined shaft and a 250-ft adit with a 40-ft winze (Moen, 1973, p. 28). REFERENCES Huntting, M. T., 1956, Inventory of Washington minerals-Part II, Metallic minerals: Washington Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 37, v. 1, 428 p.; v. 2, 67 p. Jones, E. -

Intermediate-Climbs-Guide-1.Pdf

Table of Conte TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface.......................................................................1 Triumph NE Ridge.....................................47 Privately Organized Intermediate Climbs ...................2 Vayu NW Ridge.........................................48 Intermediate Climbs List.............................................3 Vesper N Face..............................................49 Rock Climbs ..........................................................3 Wedge Mtn NW Rib ...................................50 Ice Climbs..............................................................4 Whitechuck SW Face.................................51 Mountaineering Climbs..........................................5 Intermediate Mountaineering Climbs........................52 Water Ice Climbs...................................................6 Brothers Brothers Traverse........................53 Intermediate Climbs Selected Season Windows........6 Dome Peak Dome Traverse.......................54 Guidelines for Low Impact Climbing...........................8 Glacier Peak Scimitar Gl..............................55 Intermediate Rock Climbs ..........................................9 Goode SW Couloir.......................................56 Argonaut NW Arete.....................................10 Kaleetan N Ridge .......................................57 Athelstan Moonraker Arete................11 Rainier Fuhrer Finger....................................58 Blackcomb Pk DOA Buttress.....................11 Rainier Gibralter Ledge.................................59 -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES This is why a Forest Service "recreation area" is not adequate protection for the scenery, and why a North Cascades National Park is urgently needed. Glacier Peak from White Chuck River by Dick Brooks The Wild Cascades 2 SUNRISE ON A TIDAL WAVE When the North Cascades National Park is dedicated — and it will be, the only questions being which year and with how much acreage — many of those present at the ceremonies will breathe a prayer of thanks for the June 1965 issue of Sunset Magazine. For recent immigrants to the West who may not know, Sunset has a circulation numbered in the hundreds of thousands, and a readership in the millions. It's an influential magazine. People build houses, cook meals, and plan vacations from Sunset. So, what was on the cover of the June Sunset ? A photograph of a couple of kids poking around the shores of Lyman Lake, with Bonanza and clouds beyond. And a question: "DOES WASHINGTON GET THE NEXT NATIONAL PARK?" What was inside the June Sunset ? A full 14 pages on "Our Wil derness Alps. " A two-page color-spread of Glacier Peak from Image Lake, a full-page map of our proposed park and recreation area, three large photos by Tom Miller of peaks and meadows, and three more by Bob and Ira Spring and the editors. And many thousands of words about the geography and places to go — and about the need for protection. Very much about the need for protection. We park protagonists have done some publishing about our pro posal, and are going to do some more soon, but when the score is added up, the June 1965 Sunset will be counted one of the decisive blows. -

1957

the Mountaineer 1958 COPYRIGHT 1958 BY THE MOUNTAINEERS Entered as second,class matter, April 18, 1922, at Post Office in Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and December by THE MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle 11, Wash. Clubroom is at 523 Pike Street in Seattle. Subscription price of the current Annual is $2.00 per copy. To be considered for publication in the 1959 Annual articles must be sub, mitted to the Annual Committee before Oct. 1, 1958. Enclose a self-addressed stamped envelope. For further information address The MOUNTAINEERS, P. 0. Box 122, Seattle, Washington. The Mountaineers THE PURPOSE: to explore and study the mountains, forest and water courses of the Northwest; to gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; to preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise, the natural beauty of Northwest America; to make expeditions into these regions in fulfillment of the above purposes; to encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES Paul W. Wiseman, President Don Page, Secretary Roy A. Snider, Vice-president Richard G. Merritt, Treasurer Dean Parkins Herbert H. Denny William Brockman Peggy Stark (Junior Observer) Stella Degenhardt Janet Caldwell Arthur Winder John M. Hansen Leo Gallagher Virginia Bratsberg Clarence A. Garner Harriet Walker OFFICERS AND TRUSTEES: TACOMA BRANCH Keith Goodman, Chairman Val Renando, Secretary Bob Rice, Joe Pullen, LeRoy Ritchie, Winifred Smith OFFICERS: EVERETT BRANCH Frederick L. Spencer, Chairman Mrs. Florence Rogers, Secretary EDITORIAL STAFF Nancy Bickford, Editor, Marjorie Wilson, Betty Manning, Joy Spurr, Mary Kay Tarver, Polly Dyer, Peter Mclellan. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES October-November 1974 2 THE WILD CASCADES INJ TUTS ISSUE... JHFRTT CREETR 13 3ELONMG- A" CASUALTY <3F ACCESSIBILITY, vionr-Hzcp gY CUMPER5 HE/VPlMG- FOR (MTS . RECOUBT AMP SPICtHR-D VIA A MBV U3CS-G-/NS- ROAD. CoUPTBy oF B.C. poEe^r JPEEUICPS AMJD cArrec — Mccer TIMBER CO. HOPEFULLY, . THQze CAM BE A SCJLOTICIN. "SEE PAGE -4. 4T *<- 4> *L 4F Apl E5AJ2L.y WARM I MS- IS S6UNDQ) A-S THE ^EMERfrT ECHFAMIES" CcWE PNOOPIMG- AROUNP OUR. HOUMTAIIOS # IS oEe*rHeR_MAl_ £3^pL_G>RAricU IMMlMeMT liM THE CASCADES? E-SE PAGE- <=?. A MA4SI2 MiMIHG— cTSP-SRATJciM HAS BB3M PPOPOSEE3 FOR THE VEE.FE.R. PEAK AREA EAST OF EVOKETT. SEVE RASE IO. OUR FAVORITE- IRATE. FT RPWARLHER. HAS <PAejsl«=TED> 5c«E TAHTALI2JWG- <STS>2>lP ON NEFAEJQUS &CHENE HAVING-TO Oo WITH THE MORTTH eSCLUf.pAE-M AMP A CERTAIN PRO POSED "SKI RePRT. BET Y"OU OA|NT W/=»(T TO TURKTO PAGE 13. Af #• #• 3H- TF- <3N PAGE a.o LB. IS AT ir AGA/M— THIS TIME HE'S TJEHED METEoR- OLJOGTIST A-IMD (HOODS FdETH WITH SOME FA SOJ MATING HUS/GUTX, <3fs| •£>H<M/UFAU_ N THE OASTAPES. HK- H K- HA 4<- PLUS MEWS AMDVtewg FROM CUR CofRespo^DEMrs AT—THE WONT, MEW &CCKS, AMD Moee 1. COVER PHOTO Forbidden Peak above Thunder Creek. Photo by John Warth October-November 1974 3 THE Ron Strickland TRAIL makes progress On June 10, 1974, there was introduced into Congress by Mr. Joel Pritchard H.R. 15298, "A bill to authorize a study for the purpose of determining the feasibility and the desirability of designating the Pacific Northwest Trail as a national scenic trail." OnOctoberl6, 1974, there was introduced into Congress by Senator Henry Jackson S. -

The Wild Cascades

THE WILD CASCADES June - July 1970 2 THE WILD CASCADES master plan reasonable protection for the grizzly. Wolverine, fisher, otter, marten, and other relatively rare furbearers have also MANAGEMENT STATEMENT managed to survive. Mountain goat, blacktail and mule deer are common in the area, and a few moose continue to enter NORTH CASCADES NATIONAL PARK the Park from Canada. Elk pose as a potential exotic in the Nooksack and Stehekin Drainages, but have not as yet PURPOSE OF THE AREA established permanent populations within the Park. Notable bird life includes a good population of white tailed ptarmigan North Cascades National Park . "preserves for the benefit, in the high elevations, intense numbers of bald eagles along use, and inspiration of present and future generations certain the upper Skagit Drainage, wintering trumpeter swan, and majestic mountain scenery, snowfields, glaciers, alpine large numbers of blue, ruffed, and Franklin grouse. meadows, and other unique natural features in the North Cascades Mountains." (PL 90-544) "It is a living natural Two recreation areas flank the Park. Through them pass the theater in which all can take part. Its untouched geologic Skagit and Stehekin River Valleys which drain most of the features, wildlife, and ecological communities also provide an higher Park land. Ross Lake National Recreation Area important field for scientific research."(Congressman Meeds) follows the Skagit River with its deep, cold reservoirs-Ross, Diablo, and Gorge reflecting the grandeur of the Park's ". the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of surrounding snowcapped peaks. Lake Chelan National Agriculture shall agree on the designation of areas within the Recreation Area includes the lower Stehekin Valley, one of park ..