Development, Dispossession and Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odisha Mining Corporation Limited (A GOLD CATEGORY STATE PSU)

Odisha Mining Corporation Limited (A GOLD CATEGORY STATE PSU) Training on online bidding process and Registration with MSTC Ltd. for Participation in National E-auction The Odisha Mining Corporation Ltd has decided to sell 50% of its saleable iron ore stock and 30% of its saleable chrome ore stock through national e-auction. The e-auction shall be conducted by the MSTC Ltd (A Govt. India Undertaking), the service provider. To make the buyers acquainted with the e-auction bidding process, the MSTC IT professionals will impart necessary training as per the following schedule. DATE & TIME: 20TH OF OCTOBER’2014. 21ST OF OCTOBER’2014. First Batch : 10:00 AM to 01:00 PM Single Batch : 10.00 AM to 1.00 PM Second Batch : 2.30 PM to 5.30 PM VENUE: THE INSTITUTE OF COST ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA BHUBANESWAR CHAPTER. CMA BHAWAN, A/122/2,NAYAPALLI, NILAKANTHA NAGAR,BHUBANESWAR-751012 List of buyers who will attend the training is furnished below 20TH OF OCTOBER’2014. First Batch : 10:00 AM to 01:00 PM Sl. Name & Address of the Buyer No. 1 M/s.Viraja Steel & Power (P) Ltd.At: Suniamuhan, PO: Mancheswar,Via: Chaspara, Dist: Cuttack-754027 2 M/s. Seeta Integrated Steel & Energy Limited, W/17, 1st Floor, Civil Township, Rourkela- 769004 3 M/s. Maa Trini Industries Limited, At-Balanda, PO-Kalunga,Dist-Sundargarh, Odisha 4 M/s. Sri Hardev Steels Pvt.Ltd., IDCO Plot No.28,Old Industrial Estate, Jagatpur, Cuttack 5 M/s. Steelex, At-Garhsahi, PO-Old Town, PS-Town,Dist-Keonjhar 6 M/s. -

20-08-2021 Rgh, Rourkela 02

DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY ISPAT GENERAL HOSPITAL SAIL, RSP, ROURKELA COVID-19 (RT-PCR) Test Report Date and time of reporting 20.08.2021; 06:00 P.M. Address of the referring facility/Hospital Rourkela Govt. Hospital, Rourkela SPECIMEN DETAILS Date & Time of sample collection 19.08.2021; 09:00 A.M. Date & Time of receipt of specimen 20.08.2021; 09:00 A.M. Condition of specimens received / Quality on arrival Acceptable REPORTING DETAILS Result Sr. Date of sample Sample ID Patient Name Age Sex Specimen type Mobile No. Address No. testing 2019-nCoV 1 Cov/126381 Bibaranjan Routray 16 M Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 7008507163 Basanti Colony Qn L/96 Rourkela 2 Cov/126382 Akashya Ku Panda 52 M Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 8457883130 Lathikata Sundargarh 3 Cov/126383 Naresh Ku Singh 44 M Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 9588870890 Sector 21 Rourkela 4 Cov/126384 Monalisha Badpanda 24 F Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 8327767073 Civil Township Rourkela 5 Cov/126385 Rubina Dash 25 F Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 7978510331 Jagda Rourkela 6 Cov/126386 Pinky Chouhan 31 F Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 9583404285 PH Road Rourkela 7 Cov/126387 Smruti Ranjan Biswal 28 M Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 9776155485 Chhend Rourkela 8 Cov/126388 Bibek Barik 15 M Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 7750807872 STI Rourkela 9 Cov/126389 Gayatri Bag 18 F Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 7327800212 Birmitrapur Sundargarh 10 Cov/126390 Sugyani Barik 39 F Nasal Swab 20.08.2021 Negative 9777206760 Sector 20 Mishrakhatal Rourkela 11 Cov/126391 Riya Nayar 19 F Nasal Swab -

Officename a G S.O Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Kharavela Nagar S.O Orissa Assembly S.O Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Old Town S.O (Khorda

pincode officename districtname statename 751001 A G S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar Secretariate S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Kharavela Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Orissa Assembly S.O Khorda ODISHA 751001 Bhubaneswar G.P.O. Khorda ODISHA 751002 Old Town S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751002 Harachandi Sahi S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kedargouri S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Santarapur S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bhimatangi ND S.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Gopinathpur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Itipur B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kalyanpur Sasan B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kausalyaganga B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Kuha B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sisupalgarh B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Sundarpada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751002 Bankual B.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Baramunda Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751003 Suryanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751004 Utkal University S.O Khorda ODISHA 751005 Sainik School S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Budheswari Colony S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Kalpana Square S.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Laxmisagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751006 Jharapada B.O Khorda ODISHA 751006 Station Bazar B.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Saheed Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751007 Satyanagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751007 V S S Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751008 Rajbhawan S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bapujee Nagar S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Bhubaneswar R S S.O Khorda ODISHA 751009 Ashok Nagar S.O (Khorda) Khorda ODISHA 751009 Udyan Marg S.O Khorda ODISHA 751010 Rasulgarh S.O Khorda ODISHA 751011 C R P Lines S.O Khorda ODISHA 751012 Nayapalli S.O Khorda ODISHA 751013 Regional Research Laboratory -

District Mineral Foundation Sundargarh, Odisha

INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 1 11/01/18 3:24 PM © 2018 Centre for Science and Environment Published by Centre for Science and Environment 41, Tughlakabad Institutional Area New Delhi 110 062 Phones: 91-11-29955124, 29955125, 29953394 Fax: 91-11-29955879 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cseindia.org Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 2 11/01/18 3:24 PM INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL FOUNDATION SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Centre for Science and Environment Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 3 11/01/18 3:24 PM Indicative plan district mineral foundation, Sundergarh, Odisha report.indd 4 11/01/18 3:24 PM INDICATIVE PLAN DISTRICT MINERAL SUNDARGARH, ODISHA Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ..................................................................................7 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND OF THE DISTRICT ................................................................................10 SECTION 3: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH STOCK-TAKING ..........................................15 SECTION 4: SITUATION ANALYSIS THROUGH PARTICIPATORY RURAL APPRAISAL .............................................................................................................53 -

Sl. No. TIN Name of the Dealer Address 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 LIST of DEALERS SELECTE

LIST OF DEALERS SELECTED FROM SUNDERGARH RANGE FOR TAX AUDIT DURING 2011-12 Sl. TIN Name of the dealer Address No. 1 21302000022 L & T LTD. KANSBAHAL, SUNDARGARH 2 21072000003 EAST INDIA STEEL PVT.LTD. INDUSTRIAL AREA,ROURKELA 3 SHREE GANESH METALICK 21022000079 LTD. HARIHAR PUR,KUARMUNDA 4 21352000043 PRABHU SPONGE IRON(P)LTD OCL APPROACH ROAD,ROURKELA 5 KOSHALA PLOT NO- 10/310,, PANPOSH 21812003961 AUTOMOBILES(P)LTD. ROAD,ROURKELA 6 21842000016 GRUHASTI UDYOG CHHEND BASTI, ROURKELA 7 PLOT NO-98,GOIBHANGA, INDUSTRIAL 21382000075 Time Steel & Power Ltd. ESTATE,, SUNDARGARH 8 BAJRANGA STEEL & ALLOYES 21082000046 PVT.LTD. PLOT NO-31, GOBHANGA, SUNDARGARH 9 UTKAL FLOUR MILLS(RKL) 21742000071 PVT.LTD. INDUSTRIAL AREA,, SUNDARGARH 10 21452003092 T.R.CHEMICALS LTD. BARPALLI,RAJGANGPUR 11 BARPALI KESARMAL(RAJGANGPUR) 21632000083 SURAJ PRODUCTS LTD. ROURKELA SUNDARGRAH 12 P-25,CTS, P-25,CTS, SUNDARGARH, 21312000065 M/S.SHIVA CEMENT LTD ROURKELA 13 RAJGANGPUR, RAJGANGPUR, 21062001318 HARI MACHINES L.T.D RAJGANGPUR, SUNDARGARH, 770017 14 IDCO PLOT NO- 76, INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, 21182000088 UTKAL METALLICS LTD KALUNGA, SUNDARGARH, 15 RAMABAHAL, RAJGANGPUR, 21192000034 M/S SCAN STEELS LTD. RAJGANGPUR, SUNDARGARH, 770017 16 BIJABAHAL KUARMUNDA KUARMUNDA 21202000077 PAWANJOY SPONGE IRON LTD SUNDARGARH 17 M/S SARVESH REFRACTORIES KUARMUNDA, KUARMUNDA, 21372000032 LTD KUARMUNDA, SUNDARGARH 770039 18 BALLANDA BALLANDA BALANDA,RKL 21422000053 M/S.MAA TARINI (P) LTD SUNDARGARH 19 SHREE RAM SPONGE BILAIGARH, BILAIGARH, BILAIGARH, 21442003243 &STEEL(P) LTD SUNDARGARH, 770034 20 BARPALI, BARPALLI, RAJGANGPUR, 21452003092 T.R. CHEMICALS LIMITED SUNDARGARH, 770017 21 RAJGANGPUR RAJGANGPUR 21482002542 M/S SHREE CHEM RESIN LTD . RAJGANGPUR SUNDARGARH 22 GOIBHARGA,KALUNGA 21592000008 KALINGA SPONGEIRONLTD GOIBHARGA,KALUNGA ROURKELA 23 INDERA MOTORS (PROP. -

Letter Ruo:-..."5 ....., *Rt#Ilftry O Ated:...Q

'( OF'FICE OF THE CHIEF DISTRICT MEDICAL & PUBLIC HEALTH :1 OFF'ICER. SUIIDARGARH 6nr qsv 66qr 0 6'ogtgl aqotol q'ornjqrna, Eae6o Letter ruo:-..."5 ....., *rt#ilftry o ated:...Q /... / .. /2.. / zo:.s To Dy. Director (Advertisement) - cum- Secretary to Govt. I & PR Deptt., Odisha Bhubaneswar Sub: - Advertisement ofNotice Invitation Bid, (At6e0e OtO-6gtOOt. Sir, Please publish the advertisement (Annexure- A) using minimum space as per Govt. norms in one Odia & English newspaper for one day & single edition only. The bill will be submitted to the Collector & District Magistrate, Sundargarh for payment. Yours Faithfully Chi blic Memo No- copy . lr, NIC, Sundargath for information and you are tequested to upload the details information(Annexure- A) & publish the same in the district website. Memo No Date- I// / Copy forwatded to the Notice Board, Of the CDMo/RTo/Municipalityi OIpIO/ Collectorate Sundatgath for information and necessary acnon. They are requested to display the same in their notice boatd for wide pubJication. Health Officer, Sundarga rh T ,' OF'F'ICE OF THE CHIEF DISTRICT MEDICAL & PI]BLIC HEALTH : (' OF'F'ICER, SUNDARGARII Gnt qetv 66qr g G'G,qtgrt at{G,to1 q orgiqrna, go6r6to Email : dpm [email protected] oated :...Q/. / ../. 4..lzoll. OFF'ICE OF THE CHIEF'DISTRICT MEDICAL & PUBLIC HEALTH OFF'ICE& SUNDARGARH 6nr clslv 66ql 0 G,oqtgq aqotol G. c{dqt$o,ggo6q., Website: www.sundergarh.nic.in, E-mail: [email protected] Bid Reference No. : '/1 Date: Ot /ta /Z NoncE tNVtnNG gto (areaae oro'Ggroet Bids are invited from eligible transporters to transport Khushi - Sanitary Napkins ( 61al - 96fl6 qlqq o6Qee ol6i') from the Block warehouses of sundargarh District to different Govt. -

R SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN

r DISTRICT ELEMENTARY EDUCATION PLAN 2002-10 AND ANNUAL PLAN 2002-03 DepartniGnt of School and Mass Education Government of Orissa SARVA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN ORISSA PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME AUTHORITY ORISSA, BHUBANESWAR. NIEPA DC D1 I abi-'*-^''^'^ p DOC, ; - i s ; r r s , ^ ^ J ■'=^J .icyAh!*A*^DA . ^ y : ' ■- ■ A 'iAJCA/^PUrLy.' ■ ' ^ '• / ' ♦ '^ ‘ ■',--tH?Hi^PAiiA/TA»K^iF'XLU-4^,'" '/ ^ ' — <!>>J"' \ : . " ^ ' '. ♦“••.• V O C / '•'T'w ' ■ — ■ . ■ V :\ ; >T -r.' V I N\AP OF SUWDARGARM DISTRICT v J**' / ^BANnOAHt^ V . ' mDEx / I - : ; . ?i5T«)CT aow<cy>>vv ROAIV --------------- Sl^fv»spw r PA1V.WAY -M < < 1 1 v-t*- BU»CK fUVCR. OlST*lS^ H<3R5 D TTAtA, »> gLOCK MoR-S ♦ TWAS»k. HQ.RS' ?M/>'hap£iiJT'f e HX<1 . SARVA SHIKSHA AHHIYAN suni)ar(;akm Chairman: Dr. Mona Sharrna, IAS C ollector & District Magistrate Sundargarh, District Member Secretary'! Shrl Prakash Kumar Joshi. OES District Inspector of Schools Cum District Project Officer, SSA Sundargarh Member of District Resource Group (Planning) Shri Dharani Dhar Patel Sr. Teacher Educator,DIET, Sundargarh Shri Saiiandra Kumar Mishra S! of Schools, Sundargarh MPL Shri Ganesh Ram Nnik SI of Schools, Subuega Shri Bhngirathi Sahoo SI of Schools, Bonai Shri Surendra Kumar Dash SI of Schools, Sorda, Nuagaon Shrl Devendra HIjaya Hota SI of Schools, Hemgir AllHRKVIATIONS S.S.A - SARVA SIIIKHA ARIIIVAN JI.H.S - House Mold Serve D.E.K.r - District Elementary EiliicHtion l*lan O.F.E.P.A - Orissa Primary F diieation I*ro[>ramme Aiitliority E.G.S - Education Guarantee uSclieme A.I.F, - Alternative & Innovative -

Cdpos Shall Be Teamed up with the MO of PHC/ CHC with Their Vehicles And

1 2 CHAPTER – I DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 1..1 WHY IIS IIT:: Multi-hazard disaster management plan is to help the district administration in effectively managing any disaster that is likely to be faced by the district of Sundargarh. Precise actions, procedures and responsibilities have to be laid down well in advance in order to ensure timely response in case of any disaster. Therefore a mechanism that takes into account multiple hazards and basic preparedness has to be articulated in the form of Quick Response Teams, Quick Assessment Teams, Reporting Procedures, Checklist and Handbooks. The mechanism also lays down crucial parameters requirements and organizational composition of Emergency operations centres and incident command systems. 1.2 OBJECTIVE: To reduce sustainably the disaster risk of this multi disaster prone district of Sundargarh to minimize the loss of life, property and livelihood during and after any disaster with proper plan to identify all common elements of response. This acts as a base plan or a generic / modular plan for all response activities. It provides a frame work around which other agencies and departments can outline their own activities for disaster response. The District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) has been envisaged as a preparedness plan whereby the receipts of a signal of an impending disaster would simultaneously energies and activate the mechanism for response and mitigation without loss of crucial time. This would be entailing all the participating managers to know in advance the task assigned to them and the manner of response. Identification of available resources including man power, materials, equipments and adequate delegation of financial and administrative powers are prerequisites for successful operation of the DDMP. -

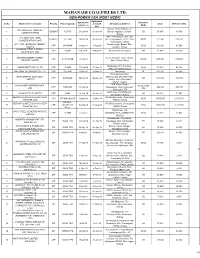

MAHANADI COALFIELDS LIMITED NON-POWER CONSUMERS HAVING FSA (POST NCDP) Mou Date for Cont

MAHANADI COALFIELDS LIMITED NON-POWER CONSUMERS HAVING FSA (POST NCDP) MoU date for cont. of extant Plant Date of signing Agreement Despatch Sl. No. Name of the Consumer Priority supply till next Destination Address Effective ACQ Capacity of Agreement expires on Mode Tranche of Linkage Auction Kapilas Cement Works, At- OCL INDIA LTD. (KAPILAS 1 CEMENT 9 LTPA 15/Dec/08 21-Jan-19 28-Feb-19 Biswali, Jagatpur, Cuttack, RD 13,000 CEMENT WORKS) Odisha New Clinkerisation Unit, Line OCL INDIA LTD. (NEW 2 CEMENT 17 LTPA 15/Dec/08 10-Jun-19 28-Jun-19 No.2, Rajgangpur-770017, Dist.- RLRD 108,500 CLINKERISATION UNIT) Sundargarh, Odisha ACC LTD., BARGARH CEMENT Cementnagar, Bardol, Dist. 1 CPP 2X15 MW 4/Aug/09 3-Aug-19 - RLRD 81,500 WORKS Bargarh, Orissa. BHASKAR STEEL & FERRO 2 CPP 4 MW 7/Aug/09 6-Aug-19 - Badatumkela, Sundargarh RD 10,830 ALLOYS PVT. LTD. BHUBANESHWAR POWER At.-Vill. Anantpur, Tahsil. Athgarh, 3 CPP 2 x 67.5 MW 10/Dec/10 14-Feb-21 - RL/RD 343,500 PRIVATE LIMITED Dist.-Cuttack, Odisha Balgopalpur,PO-Rasulpur, 4 EMAMI PAPER MILLS LTD. CPP 15 MW 1/Dec/08 27-Jan-19 30-Jan-19 RLRD 41,000 Balasore-756020,Odisha 5 NATIONAL ALUMINIUM CO. LTD. CPP 18.5 MW 30/Jul/10 23-Dec-21 - Damanjodi RL 50,500 Kharagprasad, Near NAVA BHARAT VENTURES Meramandali, Dhenkanal Rly. 6 CPP 2X32 MW 10/Jan/09 29-Jan-19 30-Jan-19 RD 167,000 LIMITED Station, Dist.-Dhenkanal- 759121, Odisha OPG Nagar, Periya OPG POWER GENERATION P. -

Of Sundargarh District, Odisha on Brick Earth Mining

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF SUNDARGARH DISTRICT, ODISHA ON BRICK EARTH MINING As per Notification No. S.O. 141(E),15th January,2016 & S.O. 3611(E), 25th July, 2018, New Delhi ,MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST & CLIMATE CHANGE (MoEF & CC) DISTRICT ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY (DEIAA) SUNDARGARH, ODISHA JULY-2020 CONTENTS Point No. DESCRIPTION Page No. 00 PREFACE 01-02 01 INTRODUCTION. 03-04 02 OVERVIEW OF MINING ACTIVITY IN THE DISTRICT. 05-09 03 GENERAL PROFILE OF THE DISTRICT. 10-11 04 GEOLOGY OF THE DISTRICT. 12-22 05 DRAINAGE OF IRRIGATION PATTERN. 23 06 LAND UTILIZATION PATTERN IN THE DISTRICT: FOREST, 24-28 AGRICULTURAL, HORTICULTURAL, MINING ETC. 07 SURFACE WATER AND GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF THE 29-32 DISTRICT. 08 RAINFALL OF THE DISTRICT AND CLIMATIC CONDITION. 33 09 DETAILS OF THE MINING LEASES IN THE DISTRICT AS PER THE 34 FORMAT. 10 DETAILS OF ROYALTY OR REVENUE RECEIVED IN LAST THREE 34 YEARS. 11 DETAILS OF PRODUCTION OF MINOR MINERAL IN LAST THREE 34 YEARS. 12 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT. 34 13 LIST OF LETTER OF INTENT (LOI) HOLDERS IN THE DISTRICT 34 ALONG WITH ITS VALIDITY AS PER THE FOLLOWING FORMAT. 14 TOTAL MINERAL RESERVE AVAILABLE IN THE DISTRICT. 34 15 QUALITY /GRADE OF MINERAL AVAILABLE IN THE DISTRICT. 34 16 USE OF MINERAL. 35 17 DEMAND AND SUPPLY OF THE MINERAL IN THE LAST THREE 35 YEARS. 18 MINING LEASES MARKED ON THE MAP OF THE DISTRICT. 35 19 DETAILS OF THE AREA OF WHERE THERE IS A CLUSTER OF 35 MINING LEASES VIZ. -

Brochure Inner.Cdr

Application No. TION OJEE-2012 INFORMATION BROCHURE ODISHA JOINT ENTRANCE EXAMINA Entrance Test for B.Tech / B.Tech(Lateral Entry) / B.Arch./B.Arch.(Lateral Entry) / MBBS / BDS / B.Pharm/ B.Pharm(Lateral Entry) / PGAT for M.Tech/M.Arch and M.Pharm MCA/MBA/PGDM/PGCM/PGDM(Executive). 13.05.2012 (Sunday) PGAT (M.Pharm) — — — The salient features of The Orissa Professional Educational Institutions (Regulation of Admission and Fixation of Fee) Act, 2007 are as follows. * Methods of admission in technical and professional educational institutions: Subject to provisions of this Act, admission of students in all the technical and private professional educational institutions, Government institutions and sponsored institutions to all seats including lateral entry seats, shall be made through JEE conducted by the Policy Planning Body followed by counselling in order of merit, in accordance with such procedure as recommended by the said body and approved by the Government of Odisha. * Reservation of seats: In a private professional educational institution other than minority institution not exceeding 5% of the approved intake may be filled up by NRI from the merit list prepared on the basis of OJEE – 2012 as per AICTE (Approval Process Handbook 2012-2013) guideline issued in this regard. Where any shortfall in filling up of seats from NRI occurs, such vacant seats may be filled up from the merit list of All India Engineering Entrance Examination (AIEEE) or All India Medical Entrance Examination, as the case may be, conducted by Central Board of Secondary Education: Provided that while filling up such vacant seats NRI shall be preferred. -

MAHANADI COALFIELDS LTD. NON-POWER FSA (POST NCDP) Agreement Agreement Despatch Sl

MAHANADI COALFIELDS LTD. NON-POWER FSA (POST NCDP) Agreement Agreement Despatch Sl. No. Name of the Consumer Priority Plant Capacity renewed Destination Address ACQ Effective ACQ expires on Mode Upto Kapilas Cement Works, At- OCL INDIA LTD. (KAPILAS 1 CEMENT 9 LTPA 21/Jan/14 21-Jan-19 Biswali, Jagatpur, Cuttack, RD 26,000 13,000 CEMENT WORKS) Odisha New Clinkerisation Unit, Line OCL INDIA LTD. (NEW 2 CEMENT 17 LTPA 10/Jun/14 10-Jun-19 No.2, Rajgangpur-770017, Dist.- RLRD 217,000 108,500 CLINKERISATION UNIT) Sundargarh, Odisha ACC LTD., BARGARH CEMENT Cementnagar, Bardol, Dist. 1 CPP 2X15 MW 3-Aug-14 3-Aug-19 RLRD 163,000 81,500 WORKS Bargarh, Orissa. BHASKAR STEEL & FERRO 2 CPP 4 MW 6-Aug-14 6-Aug-19 Badatumkela, Sundargarh RD 21,660 10,830 ALLOYS PVT. LTD. BHUBANESHWAR POWER At.-Vill. Anantpur, Tahsil. Athgarh, 3 CPP 2 x 67.5 MW 14-Feb-21 RL/RD 687,000 343,500 PRIVATE LIMITED Dist.-Cuttack, Odisha Balgopalpur,PO-Rasulpur, 4 EMAMI PAPER MILLS LTD. CPP 15 MW 27/Jan/14 27-Jan-19 RLRD 82,000 41,000 Balasore-756020,Odisha 5 NATIONAL ALUMINIUM CO. LTD. CPP 18.5 MW 23-Dec-16 23-Dec-21 Damanjodi RL 101,000 50,500 Kharagprasad, Near NAVA BHARAT VENTURES Meramandali, Dhenkanal Rly. 6 CPP 2X32 MW 29/Jan/14 29-Jan-19 RD 334,000 167,000 LIMITED Station, Dist.-Dhenkanal- 759121, Odisha OPG Nagar, Periya OPG POWER GENERATION P. RL/ RL-CUM- 7 CPP 1X80 MW 17-Jan-19 Obalapuram, Gommidipoondi, 392,000 196,000 LTD.