Munashe Mudzingwa Dissertation Final for Print.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And the Hamitic Hypothesis

religions Article Ancient Egyptians in Black and White: ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ and the Hamitic Hypothesis Justin Michael Reed Department of Biblical Studies, Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Louisville, KY 40205, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In this essay, I consider how the racial politics of Ridley Scott’s whitewashing of ancient Egypt in Exodus: Gods and Kings intersects with the Hamitic Hypothesis, a racial theory that asserts Black people’s inherent inferiority to other races and that civilization is the unique possession of the White race. First, I outline the historical development of the Hamitic Hypothesis. Then, I highlight instances in which some of the most respected White intellectuals from the late-seventeenth through the mid-twentieth century deploy the hypothesis in assertions that the ancient Egyptians were a race of dark-skinned Caucasians. By focusing on this detail, I demonstrate that prominent White scholars’ arguments in favor of their racial kinship with ancient Egyptians were frequently burdened with the insecure admission that these ancient Egyptian Caucasians sometimes resembled Negroes in certain respects—most frequently noted being skin color. In the concluding section of this essay, I use Scott’s film to point out that the success of the Hamitic Hypothesis in its racial discourse has transformed a racial perception of the ancient Egyptian from a dark-skinned Caucasian into a White person with appearance akin to Northern European White people. Keywords: Ham; Hamite; Egyptian; Caucasian; race; Genesis 9; Ridley Scott; Charles Copher; Samuel George Morton; James Henry Breasted Citation: Reed, Justin Michael. 2021. Ancient Egyptians in Black and White: ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ and Religions the Hamitic Hypothesis. -

Robert Blashek of Counsel

Robert Blashek Of Counsel Century City D: +1-310-246-6790 [email protected] Robert Blashek is a skilled and seasoned tax and investment Admissions fund lawyer. His practice covers a broad range of federal and California income tax matters, with particular emphasis on private Bar Admissions equity, mergers and acquisitions, reorganizations, financings, California bankruptcy and workouts, partnerships and strategic joint New York ventures, and general business tax planning. Rob’s clients span a broad array of industries. They include major Education film studios and entertainment companies as well as private Columbia University, J.D., 1979: equity funds that invest across a wide variety of sectors such as Harlan Fiske Stone Scholar; aerospace and consumer products. Columbia Law Review, 1977-1979 In recent years, Rob has managed the tax implications of Brown University, B.A., 1976: magna numerous acquisitions, strategic joint ventures, and financings for cum laude; Phi Beta Kappa clients such as Univision Communications, Oaktree Capital, Legendary Entertainment, Western Digital, WebMD, Houlihan Lokey, Warner Brothers, and Lions Gate Entertainment. In addition, Rob has formed or assisted in the formation of private equity investment funds for clients such as Freeman Spogli & Co., Vance Street Capital, Shamrock Capital, Black Canyon, Clarity Partners, Northstar Capital, Key Principal Partners, and Seidler Equity Partners, among others. Experience • Represented Western Digital (WD) in its acquisition of Hitachi Global Storage Technologies (Hitachi GST), a subsidiary of Hitachi, Ltd., in a cash and stock transaction valued at approximately US$4.3 billion O’Melveny & Myers LLP 1 • Represented Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios (MGM) in its acquisition of a 55 percent interest in Mark Burnett's One Three Media and LightWorkers Media. -

THE GREAT CHRIST COMET CHRIST GREAT the an Absolutely Astonishing Triumph.” COLIN R

“I am simply in awe of this book. THE GREAT CHRIST COMET An absolutely astonishing triumph.” COLIN R. NICHOLL ERIC METAXAS, New York Times best-selling author, Bonhoeffer The Star of Bethlehem is one of the greatest mysteries in astronomy and in the Bible. What was it? How did it prompt the Magi to set out on a long journey to Judea? How did it lead them to Jesus? THE In this groundbreaking book, Colin R. Nicholl makes the compelling case that the Star of Bethlehem could only have been a great comet. Taking a fresh look at the biblical text and drawing on the latest astronomical research, this beautifully illustrated volume will introduce readers to the Bethlehem Star in all of its glory. GREAT “A stunning book. It is now the definitive “In every respect this volume is a remarkable treatment of the subject.” achievement. I regard it as the most important J. P. MORELAND, Distinguished Professor book ever published on the Star of Bethlehem.” of Philosophy, Biola University GARY W. KRONK, author, Cometography; consultant, American Meteor Society “Erudite, engrossing, and compelling.” DUNCAN STEEL, comet expert, Armagh “Nicholl brilliantly tackles a subject that has CHRIST Observatory; author, Marking Time been debated for centuries. You will not be able to put this book down!” “An amazing study. The depth and breadth LOUIE GIGLIO, Pastor, Passion City Church, of learning that Nicholl displays is prodigious Atlanta, Georgia and persuasive.” GORDON WENHAM, Adjunct Professor “The most comprehensive interdisciplinary of Old Testament, Trinity College, Bristol synthesis of biblical and astronomical data COMET yet produced. -

Mark Burnett Named President of MGM Television, Digital Group

Mark Burnett Named President of MGM Television, Digital Group 12.14.2015 Mark Burnett-executive producer of such hit shows as NBC's The Voice, CBS' Survivor and ABC's Shark Tank-has been named president of MGM Television and Digital Group, the company said Monday. He'll start his new job early next year and has a five-year contract. Burnett's appointment comes as part of an overall acquisition of United Artists Media Group, an entity that's jointly held by Hearst, Burnett and his wife, Roma Downey. Some 15 months ago, MGM took a 55% stake in the production company owned by Hearst, Burnett and Downey, and at that time revived the United Artists banner with Burnett serving as CEO. Downey will remain president of the faith and family unit, LightWorkers Media. Burnett and Downey together have produced such TV miniseries as History's The Bible and NBC's follow-up, The Bible AD. To acquire United Artists, MGM bought the remaining 45 percent stake in the company. Burnett and Downey will exchange their joint 23 percent interest in UAMG for 1.34 million shares of MGM stock, valued at $90 per share. Hearst will receive $113.5 million for its 22 percent interest in UAMG. Hearst, Burnett, Downey and MGM will separately go ahead with a planned over-the-top channel, reports The Hollywood Reporter. Downey will serve as chief content officer of that operation, reports Variety. Roma Khanna, who had headed the division, is departing. Burnett, who's used to being an independent producer in charge of his own company, will report directly to Gary Barber, chairman and CEO of MGM. -

Newsmax's 100 Most Influential Evangelicals in America 3/9/21, 1:32 AM

Newsmax's 100 Most Influential Evangelicals in America 3/9/21, 1:32 AM % WATCH TV LIVE (https://www.newsmaxtv.com) & MENU (https://www.newsmax.com/t/newsmax) (https://www.newsmaxtv.com) LIVE Newsmax's 100 Most Influential Evangelicals in America From L: Billy Graham (Gerry Broome/AP), Sarah Palin (Alex Wong/Getty Images), Jerry Falwell Jr. (Nicholas Kamm/Getty Images), and Joyce Meyer (Mark Humphrey/AP). By Jen Krausz (https://www.newsmax.com/t/newsmax/section/342) Friday, 17 Nov 2017 9:07 AM ! " # $ Join in the Discussion! Evangelicals come from many different Christian denominations, but they all have a common belief in the holiness of scripture and the centrality of faith in Jesus Christ for their lives. The Pew Research Center (http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/) estimates that about 25.4 percent of Americans, or about 62 million adults, are evangelicals. The evangelical faith of these prominent Americans has shaped their lives and influenced their politics, morality, and careers, as well as their personal lives. Is Christ Really Returning? Vote in National Survey Here (http://www.newsmax.com/surveys/ReturnOfJesusChrist/When-Do-You-Think-Christ-is- Returning-/id/179/kw/default/?dkt_nbr=nflekxtw) This Newsmax list of the 100 Most Influential Evangelicals in America includes pastors, teachers, politicians, athletes, and entertainers — men and women from all walks of life whose faith leads them to live differently and to help others in a variety of ways. 1. Billy Graham — Rev. Graham has slowed down in his active ministry — he will turn 100 next November — but he's built a legacy as the greatest preacher of the gospel America has ever known. -

DVD by Title

DVD by Title Title Category Producer Run Time Rating This Ain't Prettyville-Chonda Pie Family No Whining Productions 90 PG 48 Angels Family Northern Ireland Film 90 min. NR 6 Family Adventure-The Gift, etc Family Echo Bridge Home Entertainme 0:30 G 6 Family Movies-The Wild Stallio Family Echo Bridge Home Entertainme 0:30 G 6 Family Movies-Thicker Than W Family Echo Bridge Home Entertainme G 8-Track Guy in an iPod World Family Swanberg Ministries G 90 Minutes in Heaven Family Giving Films 2 hrs. 3 min. PG-13 A Charlie Brown Christmas Children United Feature Syndicate Not Rated A Christmas Snow Family Trost Moving Pictures 111 min. NR A Christmas Without Snow Family Korty, John 96 min. G A Fruitcake Christmas- Hermie a Children Tommy Nelson 60 Min, G A Song from the Heart Family CBS 90 min. NR A Vow To Cherish Family World Wide Pictures Abe and the Amazing Promise-V Children Big Idea Inc. 53 G ACC Voice of Truth DVD Special Music Marty Collins Ace of Hearts Family Readers Digest Family Films 100 G Address Unknown Family Feature Films For Families Afred Hitchcock's Rebecca Family David O. Selznick G Alone Yet Not Alone Family Enthuse Entertainment 103 min. PG-13 Amazing Grace Family Apted, Michael 118 min. PG Amish Grace Family Larry A. Thompson Organization 89 min. PG Tuesday, April 17, 2018 Page 1 of 16 Title Category Producer Run Time Rating An Easter Carol Children Big Idea 0:49 G An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving Family Muse Entertainment 88 min. -

Un Anno Di Zapping Guida Critica Family Friendly Ai Programmi Televisivi STAGIONE TELEVISIVA - 2015/2016

Osservatorio Media del Moige Movimento Italiano Genitori a cura di Elisabetta Scala Palmira Di Marco Francesco La Rosa un anno di zapping guida critica family friendly ai programmi televisivi STAGIONE TELEVISIVA - 2015/2016 prefazione di On. Antono Martusciello indice Prefazione 7 Marida Caterini Introduzione 9 Maria Rita Munizzi, Elisabetta Scala Legenda dei simboli 11 Schede di analisi critica dei programmi 13 Indice dei programmi 323 Glossario dei termini tecnici 335 Note professionali degli autori 337 5 prefazione Una stagione televisiva molto controversa punteggiata, troppo frequentemente, da imbarazzanti cadute di stile. Palinsesti costruiti per catturare la curiosità del pubbli- co facendo leva su istinti degradanti ma ritenuti forieri di audience e quindi appetibili agli investitori pubblicitari. La tv mostra un sensibile e progressivo deterioramento dei valori etici, meno attenta al rispetto per i telespettatori e, soprattutto, per i minori. Fortunatamente, uno spiraglio esiste. E la speranza che si possa invertire il trend, fidando in un piccolo schermo a misura di famiglia, diventa visibile come un faro nella nebbia. Un anno di zapping ha, da sempre, il compito di analiz- zare i palinsesti individuando i meriti e la qualità dei pro- grammi, delle fiction, degli spot pubblicitari, dei talk show, dell’informazione e dell’intrattenimento in tutti i settori. Un lavoro lungo un anno, mai fazioso, attento e gratifi- cante, pronto a indicare la strada giusta per un’inversio- ne di tendenza verso una tv propositiva per un pubblico trasversale. Un lavoro che conosco da vicino nel quale io stessa sono stata impegnata lo scorso anno. La famiglia è la maggior fruitrice del piccolo schermo sia nelle forma convenzionale, ancora in grado di riunire tut- ti dinanzi al vecchio caro elettrodomestico, sia nella sua evoluzione resa possibile dalle nuove tecnologie. -

Buenos Aires/Argentina

CONTENTS 40 28 12 FEATURES Case Study: J.J. Abrams DEPARTMENTS Bad Robot = Good Stories. 12 From the National Executive Director The Issue at Hand Not Just a Survivor 6 Mark Burnett’s leap into On Location scripted television. 28 78 Argentina/Buenos Aires Feeling Alright Going Green Tracey Edmonds channels 85 PGA Green Production Guide goes mobile positivity via YouTube. 40 PGA Bulletin Four More Years! 88 Looking back at the 52 Member Benefits Produced By Conference. 91 Vertical Integration Mentoring Matters Brian Falk at Morning Mentors The effects of related party deals 60 92 on profit participations. Sad But True Comix 94 Network Flow! PGA ProShow Your guide to the finalists. 69 Cover photo: Zade Rosenthal May – June 2013 3 producers guild of america President MARK GORDON Vice President, Motion Pictures GARY LUCCHESI Vice President, Television HAYMA “SCREECH” WASHINGTON Vice President, New Media CHRIS THOMES Vice President, AP Council REBECCA GRAHAM FORDE Vice President, PGA East PETER SARAF Treasurer LORI McCREARY SLEEP LIKE A Secretary of Record GALE ANNE HURD President Emeritus MARSHALL HERSKOVITZ National Executive Director VANCE VAN PETTEN Representative, BICOASTAL BABY. BRANDON GRANDE PGA Northwest Board of Directors DARLA K. ANDERSON INTRODUCING FLAT BEDS ON FRED BARON CAROLE BEAMS BRUCE COHEN SELECTED FLIGHTS TO JFK. MICHAEL DE LUCA TRACEY E. EDMONDS JAMES FINO TIM GIBBONS RICHARD GLADSTEIN GARY GOETZMAN Complete Film, TV and Commercial Production Services SARAH GREEN JENNIFER A. HAIRE VANESSA HAYES Shooting Locations RJ HUME -

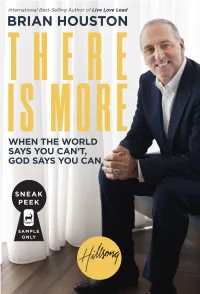

Read the First Chapter of There Is More

Praise for There Is More “Brian Houston is a dear friend who knows what God can do in your life when you surrender all. There Is More will help you learn to live a ful- filled life by trusting God to take control. I challenge you to allow this book to impact your life.” — Rick Warren, senior pastor of Saddleback Church “If you’ve ever felt that you’ve been created for something greater, pastor Brian Houston’s new book, There Is More, is exactly what you need. Packed with spiritual truth, deep insights, and practical wisdom, this book reveals how your future can hold more than you ever thought pos- sible. Read There Is More and prepare for God to build your faith, stretch your mind, and enlarge your perspective of what He wants to do through you.” — Craig Groeschel, pastor of Life.Church and author of Divine Direction: 7 Decisions That Will Change Your Life “Why is it that most of us have what we need yet still find ourselves striv- ing for more? My friend Brian Houston taps into this dichotomy and challenges us in the way that only he can. If you’ll dig into this book, I’m confident you’ll walk away with a greater expectation for your future.” — Steven Furtick, pastor of Elevation Church and New York Times best- selling author “There couldn’t be a more timely or needed book. In these confusing days, we need to be stretched where our thinking is limited, expanded where our dreams are small, and reminded that our God is not a God of There Is More TP_final.indd 1 3/5/19 3:39 PM confusion. -

Culture Shapers SUMMIT

INTERNATIONAL Culture Shapers SUMMIT Mobilizing Strategic Partnerships 1 In the last days the mountain of the Lord’s temple will be established as the highest of the mountains; it will be exalted above the hills, and all nations will stream to it. ISAIAH 2:2 Pamela and I welcome you to the 2019 Welcome! We have been looking forward to Jackie and I would like to welcome you International Culture Shapers Summit sharing this weekend together with you. to the Museum of the Bible and the 2019 Thank you for coming! We believe that collaboration is God’s strategy. Too International Culture Shapers Summit. In 1975 Bill Bright and Loren Cunningham met for often we sit back and wait on a move of God, when God This is sure to be an exciting time getting to know each the very first time. It just so happened that God spoke is waiting on a move of His people. We believe that a other, learning, sharing and being inspired. unified body of Christ, filled with His Presence, can to each of these leaders that very week about the In the journey of building Museum of the Bible we accomplish every one of His purposes. importance of the seven cultural spheres, or mind have seen how exciting it is to strive for a cause molders, as Bill Bright called them. “If we are to affect Mobilized lovers of Jesus can be the single greatest greater than any one individually, to see those efforts the culture for Jesus Christ we must impact these 7 force for good the world has ever seen. -

Hollywood Philatelist

HSC Web Site: http://www.hollywoodstampclub.com/ HSC SETARO, HOLLYWOOD STAMP CLUB DIGITAL HSC Editor HOLLYWOOD EDITION 14 August 12, PHILATELIST 2020 INDEX Milky Way Galaxy on US SURFACE MAIL IS Stamps …..…. Page 7 BACK? ….. Page 4 RUSSIA’s TRANS SIBERIAN RAILWAY on STAMPS .. Page 2 RAIN on STAMPS … Page 8 END OF WW II OCCUPA- TION STAMPS Page 5&6 Movies Studios on stamps …….. Page 3 C-130 Hercules Aircraft P. 9 1 HSC Web Site: http://www.hollywoodstampclub.com/ HSC SETARO, HOLLYWOOD STAMP CLUB DIGITAL HSC Editor HOLLYWOOD EDITION 14 PHILATELIST August 1, 2020 RUSSIA’s TRANS SIBERIAN 1916. Expansion of the railway is still tak- Today the Trans-Siberian Railway carries ing place today, with connecting rails going about 200,000 containers per year to Eu- RAILWAY on STAMPS into Mongolia, China and North Korea. rope. Russian Railways intends to at least The Trans-Siberian Railway is a network Before WW I and between WWI and II mail double the volume of container traffic on of railways connecting Moscow with or packages sent from Europe to the Far the Trans-Siberian and is developing a fleet the Russian Far East. With a length of Esat (China and Japan) would go “VIA SI- of specialised cars and increasing terminal 9,289 kilometres (5,772 miles), from Mos- BERIA” using this train. Germany would capacity at the ports by a factor of 3 to 4. cow to Vladivostok, it is the 3rd longest send many letter to Japan Via Siberia. This By 2010, the volume of traffic between railway line in the world. -

Download .Pdf

The ENTERTAINMENT AGE Fall 2015 • MEETLaw Quadrangle THE NEW VICTORS The new first-year class at Michigan Law is made up of 267 students chosen from a pool of 4,368 applicants. The class is tied for highest GPA in the School’s history and has the second-highest LSAT average score. Racial and ethnic minorities make up 24 percent of the class, while LGBT students comprise 7.5 percent. It is a group with widely varying backgrounds: ice carver, Olympic-caliber runner, FBI investigative specialist, an electrician who co-founded a Haitian solar cell company. Their culinary backgrounds are impressive: One was a pastry kitchen assistant at Zingerman’s Bakehouse; another wrote a thesis on the chemistry of baked chocolate desserts; and a third worked at an Italian winery. They represented a variety of media organizations: The New York Times, The New Yorker, Al Jazeera. The air controller from Camp Pendleton may be in some classes with2 the pilot combat trainer from the U.S. Air Force or the intelligence analyst from the Air National Guard. And the class is 50 percent male, 50 percent female. CALL PHOTOGRAPHY 05 A MESSAGE FROM DEAN WEST 06 BRIEFS 08 Townie-in-Chief 10 FEATURES 30 @UMICHLAW 30 Curriculum Changes Better Serve Student Needs 31 New Veterans Legal Clinic Will Serve Those Who Serve Us 32 A Landmark Supreme Court Term 42 GIVING 54 CLASS NOTES 54 Elder, ’77: ‘Confronting Bias’ 56 Zhang, LLM ’85: Facilitating Business Deals with Cultural Insights 60 Bakst, ’97: Advocating for Work/Family Balance 68 CLOSING 22 INDEPENDENTS’ DAY 2 FEATURES COUNSEL FOR THE BROADWAY INBOUND KARDASHIANS AND OUTBOUND 12 26 WORDS HAVE MEANING A FISH STORY 32 63 3 [ OPENING ] 5 Quotes You’ll See… …In This Issue of the Law Quadrangle 1.