Guiding Informal Activities and Settlement in the Riparian Landscape of the Volta Lake, Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8998/ppa-public-affairs-7-1-2016-pdf-28998.webp)

PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]

Vol. 7, Issue 4 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin May—Jun 2016 E-Bulletin Public Procurement Authority Accounting For Efficiency & Transparency in the Public Procurement System-The Need For Functional Procurement Units Inside this i s s u e : Editorial : Ac- counting For Efficiency &Transparency —Functional Procurement Units Online Activities : Page 2 Challenges With Establishing Functional Pro- curement Units Page 4 & 5 Corruption Along the Public Pro- curement Cycle - Page 6 & 7 (Continued on page 5) Public Procurement (Amendment) Bill, 2015 Passed. More Details Soon ………. Page 1 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin July— Aug 2016 Vol. 7, Issue 4 Online Activities List of entities that have submitted their 2016 Procurement Plans Online As At June 30 , 2016 1. Abor Senior High School 58. Fanteakwa District Assembly 2. Accra Polytechnic 59. Fisheries Commission 3. Accra College of Education 60. Foods and Drugs Board 4. Adiembra Senior High School 61. Forestry Commission 5. Adisadel College 62. Ga South Municipal Assembly 6. Aduman Senior High School 63. Ghana Aids Commission 7. Afadzato South District Assembly 64. Ghana Airports Company Limited 8. Agona West Municipal Assembly 65. Ghana Atomic Energy Commission 9. Ahantaman Senior High Schoolool 66. Ghana Audit Service 10. Akatsi South District Assembly 67. Ghana Book Development Council 11. Akatsi College of Education 68. Ghana Broadcasting Corporation 12. Akim Oda Government Hospital 69. Ghana Civil Aviation Authority 13. Akokoaso Day Senior High School 70. Ghana Cocoa Board 14. Akontombra Senior High School 71. Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons 15. Akrokerri College of Education 72. Ghana Cylinder Manufacturing Company Limited 16. Akuse Government Hospital 73. -

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

A History of German Presence in Nawuriland, Ghana

African Studies Centre Leiden, The Netherlands Gyama Bugibugi (German gunpowder): A history of German presence in Nawuriland, Ghana Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu ASC Working Paper 133 / 2016 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 E-mail [email protected] Website www.ascleiden.nl © Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu, 2016 GYAMA BUGIBUGI (German Gunpowder): A HISTORY OF GERMAN PRESENCE IN NAWURILAND, GHANA Abstract This paper discusses general political and economic issues in Nawuriland during and after German colonialism. The paper argues that the legacies of German colonialism are still largely seen and felt in Nawuriland especially in plantation projects, land and chieftaincy. Introduction The Nawuri are part of the larger Guan group in Ghana. Guans are believed to be the first settlers in modern day Ghana. They are scattered across eight of the ten regions in Ghana- namely Greater Accra, Ashanti, Eastern, Brong Ahafo, Volta, Northern, Western and Central regions. Guans speak distinct languages that are different from the major languages in Ghana examples of which include the Ga-Dangbe, Akan and Ewe. Guans in the Volta Region include Kraakye/Krachi, Akpafu/Lolobi, Buem, Nkonya, Likpe, Logba and Anum-Boso. In the central region there are the Effutu, Awutu and Senya in Winneba and Bawjiase. One finds Larteh, Anum, Mamfi and Kyerepong in the Eastern region. The Gonja, Nawuri, Nchumburu and Mpre people in the Northern and Brong Ahafo regions. Some indigenes of Kpeshie in Greater Accra also claim Guan ancestry.1 Geographically, the Nawuri are located in the North-Eastern part of Ghana. They are about 461kms away from Accra, the capital of Ghana. -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels. -

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered Voters - 2006

Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters BODWESANGO WEST 1 F021501 J S S BODWESANGO 314 2 F021502 S D A PRIM SCH BODWESANGO 456 770 BODWESANGO EAST 1 F021601 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 1 468 2 F021602 METH CHURCH BODWESANGO NO. 2 406 874 PIPIISO 1 F021701 L/A PRIM SCHOOL PIPIISO 937 2 F021702 L/A PRIM SCH AGYENKWASO 269 1,206 ABOABO 1 F021801A L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (A) 664 2 F021801B L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO2 (B) 667 3 F021802 L/A PRIM SCH ABOABO NO1 350 4 F021803 L/A PRIM SCH NKONSA 664 5 F021804 L/A PRIM SCH NYANKOMASU 292 2,637 SAPONSO 1 F021901 L/A PRIM SCH SAPONSO 248 2 F021902 L/A PRIM SCH MEM 375 623 NSOKOTE 1 F022001 L/A PRIM ARY SCH NSOKOTE 812 2 F022002 L/A PRIM SCH ANOMABO 464 1,276 ASOKWA 1 F022101 L/A J S S '3' ASOKWA 224 2 F022102 L/A J S S '1' ASOKWA 281 3 F022103 L/A J S S '2' ASOKWA 232 4 F022104 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (1) 464 5 F022105 L/A PRIM SCH ASOKWA (2) 373 1,574 BROFOYEDRU EAST 1 F022201 J S S BROFOYEDRU 352 2 F022202 J S S BROFOYEDRU 217 3 F022203 L/A PRIM BROFOYEDRU 150 4 F022204 L/A PRIM SCH OLD ATATAM 241 960 BROFOYEDRU WEST 1 F022301 UNITED J S S 1 BROFOYEDRU 130 2 F022302 UNITED J S S (2) BROFOYEDRU 150 3 F022303 UNITED J S S (3) BROFOYEDRU 289 569 16 January 2008 Page 1 of 144 Electoral Commission of Ghana List of Registered voters - 2006 Region: ASHANTI District: ADANSI NORTH Constituency ADANSI ASOKWA Electoral Area Station Code Polling Station Name Total Voters -

Togoland's Lingering Legacy: the Case of the Demarcation of the Volta

THE AUSTRALASIAN REVIEW OF AFRICAN STUDIES VOLUME 39 NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2018 CONTENTS Editorial African Studies and the ‘National Interest’ 3 Tanya Lyons Special Issue -Editorial Towards Afrocentric Counternarratives of Race and Racism in Australia 6 Kwamena Kwansah-Aidoo and Virginia Mapedzahama Special Issue Articles ‘It still matters’: The role of skin colour in the everyday life and realities of 19 black African migrants and refugees in Australia Hyacinth Udah and Parlo Singh Making and maintaining racialised ignorance in Australian nursing 48 workplaces: The case of black African migrant nurses Virginia Mapedzahama, Trudy Rudge, Sandra West and Kwamena Kwansah-Aidoo The ‘Culturally and Linguistically Diverse’ (CALD) label: A critique using 74 African migrants as exemplar Kwadwo Adusei-Asante and Hossein Adibi Black bodies in/out of place? Afrocentric perspectives and/on racialised 95 belonging in Australia Kwamena Kwansah-Aidoo and Virginia Mapedzahama Educational resilience and experiences of African students with a refugee 122 background in Australian tertiary education Alfred Mupenzi ARAS Vol.39 No.2 December 2018 1 Articles Africa Focussed Mining Conferences: An Overview and Analysis 151 Margaret O’Callaghan Africa and the Rhetoric of Good Governance 198 Helen Ware Togoland’s lingering legacy: the case of the demarcation of the Volta 222 Region in Ghana and the revival of competing nationalisms Ashley Bulgarelli The African Philosophy of Forgiveness and Abrahamic Traditions of 239 Vengeance Biko Agozino 2 ARAS Vol.39 No.2 December -

Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT on TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION

DOCUMENTS ~/lt\~TEfR · T/1107 · INDEX IJ!\!IT hwvJ J S£P ~ 4 J954 UNITED NATIONS .. .. United Nations Visiting/ Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION . "' TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS ', . TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : THIRTEENTH SESSION (28 January - 25 March 1954) '/ SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 >1 :p .. ) UNITED NATIONS United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : TIDRTEENTH SESSION (28 January-25 March 1954) SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 NOTE By its resolution 867 (XIII), adopted on 22 March 1954, the Trusteeship Council decided that the reports of the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952, including its special report on the Ewe and Togoland unifi cation problem, should be printed, together with the relevant observations of the Administering Authorities and the text of resolution 867 (XIII) concerning the Mission's reports. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. T/1107 March 1954 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Report on Togoland nnder United Kingdom administration submitted by the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 Letter dated 5 March 1953 from the Chairman of the Visiting Mission to the Secretary- General ............................................................ Foreword................................................................... 1 PART ONE Introduction 2 Itinerary . 3 PART TWO CHAPTER l. - POLITICAL ADVANCEMENT A. Integration with the Gold Coast . 5 B. Local government . -

Newmont Ghana Gold

Executive Summary ES-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Newmont Golden Ridge Limited (the “Company”), a subsidiary of Newmont Mining Corporation, is proposing to mine gold reserves at the Akyem Gold Mining Project (the “Project”) site in the Birim North District of the Eastern Region of Ghana, West Africa (Figure 1-1). The Project is located approximately 3 kilometres west of the district capital New Abirem, 133 kilometres west of Koforidua the regional capital, and 180 kilometres northwest of Accra. The proposed development lies within an area belonging to the Akyem Kotoku Paramountcy. This Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) describes the proposed Project, existing environmental conditions, potential impacts, mitigation measures, monitoring programmes, environmental management plans and closure and decommissioning approaches. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Development of the Project would involve excavation of an open pit mine and construction of waste rock disposal facilities, a Tailings Storage Facility, ore processing plant, Water Storage Facility and water transmission pipeline, sediment control structures and diversion channels, haul and access roads and support facilities (Figure ES-1). As proposed, a portion of the waste rock in the disposal facilities would be placed into the open pits during the closure and decommissioning phase of the project. Approximately 1,903 hectares are included in the Proposed Mining Area which encompasses areas required for mine development and buffer zones; additional acreage would be required to accommodate resettlement villages. Of this amount, approximately 1,428 hectares would actually be disturbed during the Project; concurrent reclamation would be accomplished when possible to reduce physical impacts on the landscape. Approximately 74 hectares of the surface disturbance associated with the Project would occur in the Ajenjua Bepo Forest Reserve. -

Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of District Assemblies For

Our Vision Our Vision is to become a world-class Supreme Audit I n s t i t u t i o n d e l i v e r i n g professional, excellent and cost-effective services. REPUBLIC OF GHANA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 This report has been prepared under Section 11 of the Audit Service Act, 2000 for presentation to Parliament in accordance with Section 20 of the Act. Johnson Akuamoah Asiedu Acting Auditor General Ghana Audit Service 21 October 2020 This report can be found on the Ghana Audit Service website: www.ghaudit.org For further information about the Ghana Audit Service, please contact: The Director, Communication Unit Ghana Audit Service Headquarters Post Office Box MB 96, Accra. Tel: 0302 664928/29/20 Fax: 0302 662493/675496 E-mail: [email protected] Location: Ministries Block 'O' © Ghana Audit Service 2020 TRANSMITTAL LETTER Ref. No.: AG//01/109/Vol.2/144 Office of the Auditor General P.O. Box MB 96 Accra GA/110/8787 21 October 2020 Tel: (0302) 662493 Fax: (0302) 675496 Dear Rt. Honourable Speaker, REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 I have the honour, in accordance with Article 187(5) of the Constitution to present my Report on the audit of the accounts of District Assemblies for the financial year ended 31 December 2019, to be laid before Parliament. 2. The Report is a consolidation of the significant findings and recommendations made during our routine audits, which have been formally communicated in management letters and annual audit reports to the Assemblies. -

The Ghanaian Dug-Out Canoe and the Canoe Carving Industry in Ghana

FAO LIBRARY AN: 314915 rIDAF/WP / 35 Mare.h1991 THE GHANAIAN DUG OUT CANOE AND THE CANOE CARVING INDUSTRY IN GHANA PAO/OLIOk 941 1 01 ISINFEWWPAT IDAF/WP/35 March 1991 THE GHANAIAN DUG-OUT CANOE AND THE CANOE CARVING INDUS1RY IN GHANA G.T. Sheves ProgrammedeDéveloppement Intégré des Péches Artisanales en Afrique de l'Ouest - DIPA ProgrammeforIntegrated DevelopmentofArtisanal Fisheries in West Africa - IDAF GCP/RAF/192/DEN With financial assistance from Denmark and in collaboration with the Republic of Benin, the Fisheries Department of FAO is implementing in West Africa a programme of small scale fisheries development, commonly called the IDAF Project. This programme is based upon an integrated approach involving production, processing and marketing of fish, and related activities ; it also involvesan active participation of the target fishing communities. This report isa working paper and the conclusions and recommendations are those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. The working papers have not necessarily been cleared for publication by the government (s) concerned nor by FAO. They may be modified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequentstages ofthe Project and issued laterin other series. The designations employed and the presentation of material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or a financing agency concerning the legal status of any country or territory, city or area, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. IDAF Project FAO Boite Postale 1369 Cotonou, R. Benin Télex : 5291 FOODAGRI Tél. 330925/330624 Fax : (229) 313649 Dr. Gordon Sheves was CTA of the Model Project Benin from 1984 to 1989. -

Northern Volta Ashanti Brong Ahafo Western Eastern Upper West

GWCL/AVRL Systems, Service Areas and Towns and Cities Served *# (!BAWKU BAWKU *# Legend Legend (! Upper East Water use in GWCL/AVRL Service Areas (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO *#!(*# GWCL/AVRL system (AVRL 2007) NAVRONGO Upp(!er East Design plant capacity BOLGATANGA *# < 2000 m^3/day *# 2000 - 5000 m^3/day water use, tanker 5000 - 10000 m^3/day *# water use, domestic connection Upper West water use, commercial connections Upper West *# 10000 - 50000 m^3/day water use, industrial connections water use, industrial connections > 50000 m^3/day *# water use, sachet producers *# water use, unmetered standpipes Served town / city (!WA WA water use, metered standpipes Population (GSS 2000) Main road !( 1000 - 5000 Water body (! 5001 - 15,000 Region *# (! 15,001 - 30,000 !*# (! 30,001 - 50,000 (YENDI Northern YENDI TAMALE Norther(!nTAMALE (!50,001 - 100,000 (!*# DAMONGO (!> 100,000 Link between system and served town Main road Water body Region Brong Ahafo Brong Ahafo *# *# *# *# (!TECHIMAN (! TECHIMAN WORAWORA ! (!*# (BEREKUM *# JASIKAN BEREKUM (!SUNYANI Volta SUNYANI Volta !(*# *# DWOMMO !(*# *# NKONYA AHENKRO! HOHOE (HOHOE (! DWOMMO BIASO *# *# BIASO *# (! M(!AMPONG *# !( TEPA # (!*# MAMPONG ACHERENSUA * !( KPANDU (! SO*#VIE KPANDU AGONA !( TEPA (!*# ANFOEGA DZANA (!*# ACHERENSUA *# (!ASOKORE KPEDZE As*#hanti *# Ashanti *# KUMASI (!KUMASI (! KONONGO *# *# *# *# (! (!HO KONONGO HO ! !( TSITO Eastern N(KAWKAW ANUM NKAWKAW *# *# E(!a*#stern ANYINAM !( (! (! OSINOBEGORO *# KWABENG *#!( *# (! BUNSO *# (! ASUOM JUAPONG *# *#*# (! NEW TAFO # !( # NEW TAFO * -

Boundaries 1

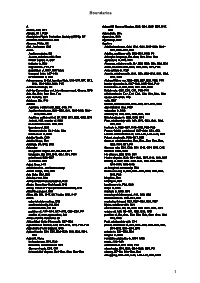

Boundaries A Agbovi IV, Nene of Kpetoe, G32, G34, G36–G37, K17, Abéné, A40, G17 N18 Ablode, K17, K20 Agbrodrafo, B15 Aboriginies Rights Protection Society (ARPS), D7 Agoe clan, B19 Abraham Commission, K33 Agomlanyi, G32 Abrams, Philip, A5 Agotime Abri, Asafoatse, G35 Adaklu land case, G34_G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– Accra N19, N26–N27, P20 Agotime origins, B8 Adaklu, realitions with, B12–B13, N19, P4 Asante, relations with, B29 Adangbe language, B8, G40, N15, N19, N28 British traders in, C37 agriculture in, E29, M11 industry in, K25 Akwamu, relations with, B7, B22–B23, B25, B28, B31 migration to, F21, P9 Ando, relations with, G35, G39, N16, N19, P20 population of, M47, M47 table Anlo settlers in, P20 transport links, F37–F38 Asante, relations with, B14, B23, B28–B30, B31, C36, in World War II, H10 G31, G39 Acheampong, Lt-Col. Ignatius Kutu, L18–L19, M7, M12, Atukpui-Nyive war, B23–B25, B27, B28, N22, P19 M14, M21–M22, M49, P15 border dynamics in, N37–N44, N45–N46, P10 Achimota College, K3 boundaries of, B20, B30, B31, E30, G29 Ad Hoc Committee on Union Government, Ghana, M20 British rule, C37, C38, C41, E35–E41 Ada, B8, B17, B22–B23, F26 chieftancies in, E27, E31–E34, K16–K18, N25, N40 Ada Manche, C37 cocoa cultivation, F25 Adabara, Etu, F44 cults, B27 Adaklu Danish, relations with, B13–B16, B17–B18, B25 Agotime, conflict with, B22, C36, P4 dipo initiation rites, N30 Agotime land case, G34–G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– education in, N42 N19, N26–N27 ethnicity of, B26, G28, G40, G41, N44 Agotime, settlement of, B7, B12–B13, B20, G32, G33 Ewe language in, G26, G40, N19 Ankrah, H.B.