Togoland's Lingering Legacy: the Case of the Demarcation of the Volta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8998/ppa-public-affairs-7-1-2016-pdf-28998.webp)

PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]

Vol. 7, Issue 4 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin May—Jun 2016 E-Bulletin Public Procurement Authority Accounting For Efficiency & Transparency in the Public Procurement System-The Need For Functional Procurement Units Inside this i s s u e : Editorial : Ac- counting For Efficiency &Transparency —Functional Procurement Units Online Activities : Page 2 Challenges With Establishing Functional Pro- curement Units Page 4 & 5 Corruption Along the Public Pro- curement Cycle - Page 6 & 7 (Continued on page 5) Public Procurement (Amendment) Bill, 2015 Passed. More Details Soon ………. Page 1 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin July— Aug 2016 Vol. 7, Issue 4 Online Activities List of entities that have submitted their 2016 Procurement Plans Online As At June 30 , 2016 1. Abor Senior High School 58. Fanteakwa District Assembly 2. Accra Polytechnic 59. Fisheries Commission 3. Accra College of Education 60. Foods and Drugs Board 4. Adiembra Senior High School 61. Forestry Commission 5. Adisadel College 62. Ga South Municipal Assembly 6. Aduman Senior High School 63. Ghana Aids Commission 7. Afadzato South District Assembly 64. Ghana Airports Company Limited 8. Agona West Municipal Assembly 65. Ghana Atomic Energy Commission 9. Ahantaman Senior High Schoolool 66. Ghana Audit Service 10. Akatsi South District Assembly 67. Ghana Book Development Council 11. Akatsi College of Education 68. Ghana Broadcasting Corporation 12. Akim Oda Government Hospital 69. Ghana Civil Aviation Authority 13. Akokoaso Day Senior High School 70. Ghana Cocoa Board 14. Akontombra Senior High School 71. Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons 15. Akrokerri College of Education 72. Ghana Cylinder Manufacturing Company Limited 16. Akuse Government Hospital 73. -

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

A History of German Presence in Nawuriland, Ghana

African Studies Centre Leiden, The Netherlands Gyama Bugibugi (German gunpowder): A history of German presence in Nawuriland, Ghana Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu ASC Working Paper 133 / 2016 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 E-mail [email protected] Website www.ascleiden.nl © Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu, 2016 GYAMA BUGIBUGI (German Gunpowder): A HISTORY OF GERMAN PRESENCE IN NAWURILAND, GHANA Abstract This paper discusses general political and economic issues in Nawuriland during and after German colonialism. The paper argues that the legacies of German colonialism are still largely seen and felt in Nawuriland especially in plantation projects, land and chieftaincy. Introduction The Nawuri are part of the larger Guan group in Ghana. Guans are believed to be the first settlers in modern day Ghana. They are scattered across eight of the ten regions in Ghana- namely Greater Accra, Ashanti, Eastern, Brong Ahafo, Volta, Northern, Western and Central regions. Guans speak distinct languages that are different from the major languages in Ghana examples of which include the Ga-Dangbe, Akan and Ewe. Guans in the Volta Region include Kraakye/Krachi, Akpafu/Lolobi, Buem, Nkonya, Likpe, Logba and Anum-Boso. In the central region there are the Effutu, Awutu and Senya in Winneba and Bawjiase. One finds Larteh, Anum, Mamfi and Kyerepong in the Eastern region. The Gonja, Nawuri, Nchumburu and Mpre people in the Northern and Brong Ahafo regions. Some indigenes of Kpeshie in Greater Accra also claim Guan ancestry.1 Geographically, the Nawuri are located in the North-Eastern part of Ghana. They are about 461kms away from Accra, the capital of Ghana. -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels. -

Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT on TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION

DOCUMENTS ~/lt\~TEfR · T/1107 · INDEX IJ!\!IT hwvJ J S£P ~ 4 J954 UNITED NATIONS .. .. United Nations Visiting/ Mission to .. Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION . "' TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS ', . TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : THIRTEENTH SESSION (28 January - 25 March 1954) '/ SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 >1 :p .. ) UNITED NATIONS United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 REPORT ON TOGOLAND UNDER UNITED KINGDOM ADMINISTRATION TOGETHER WITH RELATED DOCUMENTS TRUSTEESHIP COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS : TIDRTEENTH SESSION (28 January-25 March 1954) SUPPLEMENT No. 2 NEW YORK, 1954 NOTE By its resolution 867 (XIII), adopted on 22 March 1954, the Trusteeship Council decided that the reports of the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952, including its special report on the Ewe and Togoland unifi cation problem, should be printed, together with the relevant observations of the Administering Authorities and the text of resolution 867 (XIII) concerning the Mission's reports. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. T/1107 March 1954 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Report on Togoland nnder United Kingdom administration submitted by the United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in West Africa, 1952 Letter dated 5 March 1953 from the Chairman of the Visiting Mission to the Secretary- General ............................................................ Foreword................................................................... 1 PART ONE Introduction 2 Itinerary . 3 PART TWO CHAPTER l. - POLITICAL ADVANCEMENT A. Integration with the Gold Coast . 5 B. Local government . -

Report of the Auditor General on the Accounts of District Assemblies For

Our Vision Our Vision is to become a world-class Supreme Audit I n s t i t u t i o n d e l i v e r i n g professional, excellent and cost-effective services. REPUBLIC OF GHANA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 This report has been prepared under Section 11 of the Audit Service Act, 2000 for presentation to Parliament in accordance with Section 20 of the Act. Johnson Akuamoah Asiedu Acting Auditor General Ghana Audit Service 21 October 2020 This report can be found on the Ghana Audit Service website: www.ghaudit.org For further information about the Ghana Audit Service, please contact: The Director, Communication Unit Ghana Audit Service Headquarters Post Office Box MB 96, Accra. Tel: 0302 664928/29/20 Fax: 0302 662493/675496 E-mail: [email protected] Location: Ministries Block 'O' © Ghana Audit Service 2020 TRANSMITTAL LETTER Ref. No.: AG//01/109/Vol.2/144 Office of the Auditor General P.O. Box MB 96 Accra GA/110/8787 21 October 2020 Tel: (0302) 662493 Fax: (0302) 675496 Dear Rt. Honourable Speaker, REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT ASSEMBLIES FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 I have the honour, in accordance with Article 187(5) of the Constitution to present my Report on the audit of the accounts of District Assemblies for the financial year ended 31 December 2019, to be laid before Parliament. 2. The Report is a consolidation of the significant findings and recommendations made during our routine audits, which have been formally communicated in management letters and annual audit reports to the Assemblies. -

Guiding Informal Activities and Settlement in the Riparian Landscape of the Volta Lake, Ghana

REStrUctURING THE RESETTLED LANDSCAPE GUIDING INFORMAL ACTIVITIES AND SETTLEMENT IN THE RIPARIAN LANDSCAPE OF THE VOLTA LAKE, GHANA. REStrUctURING THERESETTLED LANDSCAPE GUIDING INFORMAL ACTIVITIES AND SETTLEMENT IN THE RIPARIAN LANDSCAPE OF THE VOLTA LAKE, GHANA Major Thesis Landscape Architecture Wageningen, November 2009 Wageningen University and Research Centre Master Landscape Architecture & Spatial Planning Major Thesis Landscape Architecture [LAR-80430] Authors: Supervisor & examiner: M.A. [Miranda] Schut Dr. Ir. I. [Ingrid] Duchhart [WUR] signature date signature date E.A. [Ilse] Verwer Dr. Ir. K. [Kelly] Shannon [KUL] signature date signature date Ir. V. [Viviana] d’Auria [KUL] signature date In collaboration with Examiner Ph.D. Professor J. [Jusuck] Koh [WUR] signature date Supported by EFL STICHTING The artificial Volta Lake in Ghana is one of many tivities and settlement. This incentive planning ap- artificial lakes in Sub-Sahara Africa, but distinc- proach uses limited financial resources and mini- tive because of its size [85.000 km2] and age [the mal land ownership. The positioning of social facili- Akosombo Dam was finished in 1964]. In the ripar- ties provides the basic structure in this open-ended STRACT ian landscape around the Volta Lake, informal ac- development. The design integrates several solu- B A tivities and settlement is occurring on a large scale, tions tackling problems concerning problematic despite planning precautions. The lake and the access, erratic and unreliable power supply, access 0.I riparian landscape offer a relatively large abun- to basic services like clean drinking water, environ- dance of natural resources, providing the potential mental sanitation and health care and living con- for settlers to conduct multiple livelihood activities ditions and outdoor space. -

Boundaries 1

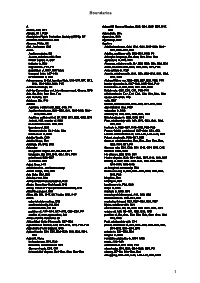

Boundaries A Agbovi IV, Nene of Kpetoe, G32, G34, G36–G37, K17, Abéné, A40, G17 N18 Ablode, K17, K20 Agbrodrafo, B15 Aboriginies Rights Protection Society (ARPS), D7 Agoe clan, B19 Abraham Commission, K33 Agomlanyi, G32 Abrams, Philip, A5 Agotime Abri, Asafoatse, G35 Adaklu land case, G34_G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– Accra N19, N26–N27, P20 Agotime origins, B8 Adaklu, realitions with, B12–B13, N19, P4 Asante, relations with, B29 Adangbe language, B8, G40, N15, N19, N28 British traders in, C37 agriculture in, E29, M11 industry in, K25 Akwamu, relations with, B7, B22–B23, B25, B28, B31 migration to, F21, P9 Ando, relations with, G35, G39, N16, N19, P20 population of, M47, M47 table Anlo settlers in, P20 transport links, F37–F38 Asante, relations with, B14, B23, B28–B30, B31, C36, in World War II, H10 G31, G39 Acheampong, Lt-Col. Ignatius Kutu, L18–L19, M7, M12, Atukpui-Nyive war, B23–B25, B27, B28, N22, P19 M14, M21–M22, M49, P15 border dynamics in, N37–N44, N45–N46, P10 Achimota College, K3 boundaries of, B20, B30, B31, E30, G29 Ad Hoc Committee on Union Government, Ghana, M20 British rule, C37, C38, C41, E35–E41 Ada, B8, B17, B22–B23, F26 chieftancies in, E27, E31–E34, K16–K18, N25, N40 Ada Manche, C37 cocoa cultivation, F25 Adabara, Etu, F44 cults, B27 Adaklu Danish, relations with, B13–B16, B17–B18, B25 Agotime, conflict with, B22, C36, P4 dipo initiation rites, N30 Agotime land case, G34–G39, G41, N15–N16, N18– education in, N42 N19, N26–N27 ethnicity of, B26, G28, G40, G41, N44 Agotime, settlement of, B7, B12–B13, B20, G32, G33 Ewe language in, G26, G40, N19 Ankrah, H.B. -

Provision of Transverse and Longitudinal Transport Services on the Volta Lake in the Krachi Catchment Area

PROVISION OF TRANSVERSE AND LONGITUDINAL TRANSPORT SERVICES ON THE VOLTA LAKE IN THE KRACHI CATCHMENT AREA By JOSHUA KWAME ADDAE (B.A. Integrated Development Studies) A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Development Policy and Planning October, 2014. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my work towards the Master of Science degree and that to the best of my knowledge it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been presented for the award of any Degree of the University except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Joshua Kwame Addae (PG7189512) ………………… …………………. (Student name & ID number) Signature Date Certified by Prof. K. K. Adarkwa ………………… …………………. (Supervisor‟s Name) Signature Date Certified by Dr. Daniel K. B. Inkoom ………….………. ....………………. (Head of Department) Signature Date ii ABSTRACT Transportation is responsible for personal mobility; provides access to services, jobs, and leisure activities; and it is critical to the delivery of consumer goods. Water based transport is effective because, operating costs of fuel are low and environmental pollution is lower than for corresponding volumes of movement by road, rail or air. A major advantage is that the main infrastructure – the waterway – is often naturally available. Inland water transport on the Volta Lake to Krachi and its surrounding communities is unavoidable on account of peninsula feature. Transport services on the lake are thus important to help the residents in the area to have access to socio economic facilities including education, health delivery services and market centres. -

Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into the Creation of New Regions

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS EQUITABLE DISTRIBUTION OF NATIONAL RESOURCES FOR BALANCED DEVELOPMENT PRESENTED TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA NANA ADDO DANKWA AKUFO-ADDO ON TUESDAY, 26TH DAY OF JUNE, 2018 COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO In case of reply, the CREATION OF NEW REGIONS number and date of this Tel: 0302-906404 Letter should be quoted Email: [email protected] Our Ref: Your Ref: REPUBLIC OF GHANA 26th June, 2018 H.E. President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo President of the Republic of Ghana Jubilee House Accra Dear Mr. President, SUBMISSION OF THE REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF INQUIRY INTO THE CREATION OF NEW REGIONS You appointed this Commission of Inquiry into the Creation of New Regions (Commission) on 19th October, 2017. The mandate of the Commission was to inquire into six petitions received from Brong-Ahafo, Northern, Volta and Western Regions demanding the creation of new regions. In furtherance of our mandate, the Commission embarked on broad consultations with all six petitioners and other stakeholders to arrive at its conclusions and recommendations. The Commission established substantial demand and need in all six areas from which the petitions emanated. On the basis of the foregoing, the Commission recommends the creation of six new regions out of the following regions: Brong-Ahafo; Northern; Volta and Western Regions. Mr. President, it is with great pleasure and honour that we forward to you, under the cover of this letter, our report titled: “Equitable Distribution of National Resources for Balanced Development”. -

Nkwanta South District

NKWANTA SOUTH DISTRICT Copyright (c) 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Nkwanta South District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

The Volta Region

THE VOLTA REGION A Guide to Tourists and Investors THE VOLTA REGION THE VOLTA REGION Republic of Ghana A Guide to Tourists and Investors September, 2011 A Guide to Tourists and Investors Volta Region Development Agency P. O. Box 523 Ho, Volta Region Ghana Tel: 0362028071 [email protected] THE VOLTA REGION Foreword The Volta Region and the Volta Basin are a treasure-trove of vari- ous important minerals and other natural resources, including gold, diamonds, copper, lead, iron ore, and oil and gas. The region also has fertile agricultural lands, enormous potentials for large-scale fish farming, large deposits of clay for brick and ce- ramics production, extensive salt deposits along the coast, and the largest variety of tourist attractions. The friendly and peace-loving people of the region have made it one of the most peaceful places in Ghana, and indeed in the entire universe. It is also a nature-loving tourist’s haven. We seek to present, through this publication, the hidden natural treasures of the region, and to expose its tourist attractions and in- vestment potentials. We aim to encourage entrepreneurs and businessmen and women from all over the world to take advantage of the favourable invest- ment environment, the promising natural resource sector and im- proved infrastructural network, to invest in the Volta Region. A Guide to Tourists and Investors THE VOLTA REGION Building a prosperous and harmonious region is the mission of the Volta Region Development Agency. We hope this modest publica- tion will give prospective visitors and investors a reasonable appre- ciation of the land, its natural resources, and its people.