I INTRODUCTION and RESEARCH DESIGN in India As Well As in Most

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farmer Database

KVK, Trichy - Farmer Database Animal Biofertilier/v Gende Commun Value Mushroo Other S.No Name Fathers name Village Block District Age Contact No Area C1 C2 C3 Husbandry / Honey bee Fish/IFS ermi/organic Others r ity addition m Enterprise IFS farming 1 Subbaiyah Samigounden Kolakudi Thottiyam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 57 9787932248 BC 2 Manivannan Ekambaram Salaimedu, Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 58 9787935454 BC 4 Ixora coconut CLUSTERB 3 Duraisamy Venkatasamy Kolakudi Thottiam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787936175 BC Vegetable groundnut cotton EAN 4 Vairamoorthy Aynan Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 33 9787936969 bc jasmine ixora 5 subramanian natesan Sirupathur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787942777 BC Millet 6 Subramaniyan Thirupatur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787943055 BC Tapioca 7 Saravanadevi Murugan Keelakalkandarkottai THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI F 42 9787948480 SC 8 Natarajan Perumal Kattukottagai UPPILIYAPURAM TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 47 9787960188 BC Coleus 9 Jayanthi Kalimuthu top senkattupatti UPPILIYAPURAM Tiruchirappalli F 41 9787960472 ST 10 Selvam Arunachalam P.K.Agaram Pullampady TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 23 9787964012 MBC Onion 11 Dharmarajan Chellappan Peramangalam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 68 9787969108 BC sugarcane 12 Sabayarani Lusis prakash Chinthamani Musiri Tiruchirappalli F 49 9788043676 BC Alagiyamanavala 13 Venkataraman alankudimahajanam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 67 9788046811 BC sugarcane n 14 Vijayababu andhanallur andhanallur TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 30 9788055993 BC 15 Palanivel Thuvakudi THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 65 9788056444 -

Tamilnadu E-Governance Agency Thiruchirappalli(D)

Tamilnadu e-Governance Agency No. 5/9, TNHB Building,Kavingar Bharathidasan Road, Cresent Street, Alwarpet Chennai - 600 018. Thiruchirappalli(D) - Srirangam(T) Centre Details Centre name Address Revenue details Local bodies details Agency User ID name 1 Amma Mandapam Hope Amma Mandapam, Srirangam, Srirangam(T) Tiruchirappalli(Cor) MIS tri_cor_001 Centre - COR Trichy, - 620006 srirangam firka(F) Srirangam(Z) Mail : [email protected] ANTHANALLUR(RV) 16(W) Phone : 8681033196 2 ULB - Trichy Srirangam Zonal Office Centre, Trichy, - 620006 Srirangam(T) Tiruchirappalli(Cor) ELC tri_elc_ma03,T Corporation - ELCOT Mail : [email protected] srirangam firka(F) Srirangam(Z) NELCTRI009-0 Phone : 9578310794 VELLITHIRUMUTTHAM( 3(W) 1 RV) 3 Maruthandakurichi Maruthandakurichi Panchayat office, Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa01,T Panchayat - ELCOT Kulumani Main Road, Seerathoppu (PO), KULUMANI Firka(F) Kulumani(VP) NELCTRI011-0 Trichy, - 620102 KULUMANI(RV) 1 Mail : [email protected] Phone : 9865283828 4 Punganur Panchayat - Punganur panchyat office, Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa02,T ELCOT Mela street, punganur, Manikandam Firka(F) Puliyur(VP) NELCTRI007-0 Trichy, - 620009 PULIYUR(RV) 1 Mail : [email protected] Phone : 7402613301 5 Natchikurichi Panchayat Natchikurichi Panchayat office, Somarasampettai (PO), Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa03,T - ELCOT Village Panchayat – Natchikurichi, - 620102 Somarasampettai firka(F) Kambarasampettai(VP) NELCTRI004-0 Mail : [email protected] NACHIKURICHI(RV) -

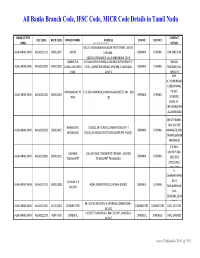

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Address STD CODE Phone No Fax No E-Mail Address 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT 2005 NAME AND ADDRESS OF ASSISTANT PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICERS - COMMERCIAL TAXES DEPT. Assistant Public Sl.No. Name of the Office Information Officer/Public Address STD CODE Phone No Fax No E-Mail Address Information Officer Deputy Commissioner Office of the Commissioner of Commercial Commissioner of Commercial 28546944,28514656 1 (Special Cell) Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Taxes Extn .29 Information Officer 600 005. Asst.Commissioner (General Office of the Commissioner of Commercial 28546944, 28514656 Services) Assistant Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Extn .25 Information Officer 600 005. Asst.Commissioner (Public Office of the Commissioner of Commercial 28546944,28514656 Relations)/ Assistant Public Taxes, Chepauk, Ezhilagam Complex, Chennai 044 Extn .44 Information Officer 600 005. Personal Asst. to Joint Office of the Joint Commissioner (Commercial Joint Commissioner,Chennai( 2 Commissioner, Chennai rd 044 28295551, 28294396 North ) Taxes) Chennai (North) 3 Floor PAPJM (North)/ PIO Buildings, No. 1 Greams Road, Chennai -6 Office of the Assistant Commissioner (CT) Zone- Asst.Commissioner, Zone - I 3 Asst. Commissioner - Zone - I rd 044 28295695 -- -- /PIO 1 3 Floor PAPJM Buildings, No. 1 Greams Road, Chennai -6 Office of the Commercial Tax Officer, Harbour I Commercial Tax Officer, CTO, Harbour - I Assessment Circle, Dass India Tower 044 25248777 - - Harbour - I /PIO Building,No.3,2nd Lane Beach,Chennai-1 Office of the Commercial -

Trichy FOC Centres Phone Numbers Land Line Mobile 9445853

Name of the Region : Trichy Fuse Off Call Centres Name of the Circle : Trichy Phone Numbers FOC Centres Land Line Mobile For BSNL Users:1912 9445853479 - TRICHY For others:04311912 9445853480 Name of the Circle : Karur Phone Numbers FOC Centres Land Line Mobile KARUR 1912 94445854093 Name of the Circle : Pudukkottai Phone Numbers FOC Centres Land Line Mobile Pudukkottai 04322-221523 ----- Landline Numbers Name of the Circle : TRICHY Elecy. Distn. Circle/Metro Section Sub-Division Division Section Name Phone No Sub Division Phone No Division Phone No Name Name Thennur 0431-2794237 Thillainagar 0431-2791467 0431 - Woraiyur 0431 -2794237 THENNUR 2794237 Srinivasanagar 0431 -2794237 Con-II/Rockfort 0431-2793220 Con-I/Urban/Trichy 0431-2793220 Rockfort 0431-2793220 0431- Cinthamani 0431 -2793220 ROCKFORT 0431 - 2793220 Maingauardgate 0431 -2793220 URBAN 2793131 110KV/K.Pettai 0431 -2706443 Palakkarai 0431-2793220 Gandhimarket 0431-2793220 Senthaneerpuram 0431 -2793220 0431 - PALAKKARAI Junction 0431 -2414749 2793220 Ponnagar 0431-2481858 Mahalakshminagar 0431 -2202525 Cantonment 0431-2460148 Mannarpuram 0431-2420145 Subramaniapuram 0431 -2420145 Up graded Code No: Sembattu 0431 -2341924 section 0431 Crawford 0431 -2471880 KK Nagar 0431 -2341032 Rural/ Trichy 0431-2422301 EAST 0431 Manikandam 0431-2680300 /TRICHY 242223 Tiruparaithurai 0431-2614322 RURAL / 0431- TRICHY 2422301 Somarasampettai 0431-2607271 110 KV SS/ Ammapettai 0431-2680300 110 KV SS/Alundur 0431-2680514 Tiruverumbur 0431-2512773 THIRUVERUMB 0431- Navalpattu 0431-2512224 UR -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth A Guide to Heaven – The past and present of Srirangam Pradeep Chakravarthy 3/1/2010 For the Tag Heritage Lecture Series 1 ARCHIVAL PICTURES IN THE PRESENTATION © COLLEGE OF ARTS, OTHER IMAGES © THE AUTHOR 2 Narada! How can I speak of the greatness of Srirangam? Fourteen divine years are not enough for me to say and for you to listen Yama’s predicament is worse than mine! He has no kingdom to rule over! All mortals go to Srirangam and have their sins expiated And the devas? They too go to Srirangam to be born as mortals! Shiva to Narada in the Sriranga Mahatmaya Introduction Great civilizations have been created and sustained around river systems across the world. India is no exception and in the Tamil country amongst the most famous rivers, Kaveri (among the seven sacred rivers of India) has been the source of wealth for several dynasties that rose and fell along her banks. Affectionately called Ponni, alluding to Pon being gold, the Kaveri river flows in Tamil Nadu for approx. 445 Kilometers out of its 765 Kilometers. Ancient poets have extolled her beauty and compared her to a woman who wears many fine jewels. If these jewels are the prosperous settlements on her banks, the island of Srirangam 500 acres and 13 kilometers long and 7 kilometers at its widest must be her crest jewel. Everything about Srirangam is massive – it is at 156 acres (perimeter of 10,710 feet) the largest Hindu temple complex in worship after Angkor which is now a Buddhist temple. -

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL of INDIAN HISTORY and CULTURE

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE December 2015 Twenty First Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH (affiliated to the University of Madras) The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA December 2015, Twenty First Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. A. Chandrsekharan Dr. V. Balambal Dr. S. Vasanthi Dr. Chitra Madhavan Dr. G. Chandhrika Published by Dr. Nanditha Krishna C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Sub editing by : Mr. Rudra Krishna & Mr. Narayan Onkar Layout Design : Mrs.T. PichuLakshmi Subscription Rs. 150/- (for 1 issue) Rs. 290/- (for 2 issues) 2 December 2015, Twenty First Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS 1 The Conflict Between Vedic Aryans And Iranians 09 by Dr. Koenraad Elst 2 Some Kushana Images of Karttikeya from Mathura 39 by Dr. V. Sandhiyalakshmi 3 Para Vasudeva Narayana 43 by Dr. G. Balaji 4 Pallava-Kadamba Interlude in Kerala: An Epigraphical Study 50 by Dhiraj, M.S. 5 Temple Managerial Groups in Early Keralam 69 by Anna Varghese 6 Irrigation and Water Supply During the Kakatiya Period 86 by Dr. D. Mercy Ratna Rani 7 Traditional Health Care in Ancient India with Reference to Karnataka 101 by Dr. -

Geoinformatics for Concentration of Crime Against Women in Tiruchirappalli City, Tamil Nadu

Journal of Information and Computational Science ISSN: 1548-7741 GEOINFORMATICS FOR CONCENTRATION OF CRIME AGAINST WOMEN IN TIRUCHIRAPPALLI CITY, TAMIL NADU. P. Mary Santhi1, S. Balaselvakumar2 K. Kumaraswamy3 1Research Scholar 2Assistant Professor & 3Emeritus Professor 1&2 Department of Geography, Periyar E.V.R. College (Autonomous), Tiruchirappalli – 620 023 3Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 Affiliated to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 Abstract This paper is an attempt to mapping and analysing the concentration of crimes against women in Tiruchirappalli city for the years 2012 to 2017. The concentration score of crimes against women (rape, dowry death, molestation, kidnapping, cruelty by husband, dowry Prohibition Act 1961 and POCSO Act, 2012) recorded in each of All Women Police Station (AWPS) has been calculated and it reveals that the high concentration of crime rape was recorded in AWPS Golden rock with 1.4%, dowry death in AWPS Srirangam with 3.4%, molestation in AWPS Cantonment with 0.6%, cruelty by husband in AWPS Srirangam with 1.4%, dowry Prohibition Act 1961 cases in AWPS Fort with 1.7% and POCSO Act, 2012 cases in AWPS Golden rock with 1.4%. The low concentration of crime rape and cruelty by husband was recorded in AWPS Srirangam and Golden rock with 0.9% and molestation and kidnapping in AWPS Fort and Cantonment with 0.1 %. Among all four AWPS, the AWPS Golden rock and Srirangam had recorded the maximum concentration of crimes against women when the total crimes in a particular police station were compared to the total crimes in the study area. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 27.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Maasi 29, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 553-619 Notice .. 620 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8416. I, Barakathu Nisha, wife of Thiru Syed Ahamed 8419. My son, P. Jayakodi, born on 10th October 2010 Kabeer, born on 1st April 1966 (native district: (native district: Virudhunagar), residing at Old No. 8-23, New Ramanathapuram), residing at Old No. 4-66, New No. 4/192, No. 8-99, West Street, Veeranapuram, Kalingapatti, Chittarkottai Post, Ramanathapuram-623 513, shall henceforth Sankarankoil Taluk, Tirunelveli-627 753, shall henceforth be be known as BARAKATH NEESHA. known as V.P. RAJA. BARAKATHU NISHA. M. PERUMALSAMY. Ramanathapuram, 4th March 2013. Tirunelveli, 4th March 2013. (Father.) 8420. I, Sarika Kantilal Rathod, wife of Thiru Shripal, born 8417. I, S Rasia Begam, wife of Thiru M. Sulthan, born on on 3rd February 1977 (native district: Chennai), residing at 2nd June 1973 (native district: Dindigul), residing at Old No. 140-13, Periyasamy Road, R.S. Puram Post, Coimbatore- No. 4/115-E, New No. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 3581147 29

Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 3581147 29/06/2017 SUDHIR KUMAR L-83, BLOCK-L, J.J.COLONY RAGHUBIR NAGAR, DELHI Proprietor Address for service in India/Attorney address: SAARTHI BHATIA 5/19, Kirti Nagar Industrial Area, New Delhi-110015. Used Since :01/11/2014 DELHI PINS (HAIR) 5898 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 3684375 22/11/2017 MR. SATISH AHUJA PROP. OF PRECISION INDUSTRIAL ENTERPRISES 768, FARIDPURI, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI-110008 PROP. Address for service in India/Attorney address: TMR SOLUTIONS M - 10, ANUPAM BHAWAN COMMPERCIAL COMPLEX, ADADPUR, DELHI - 110033 Proposed to be Used DELHI LACE AND EMBROIDERY, RIBBONS AND BRAID, BUTTONS, HOOKS AND EYES, PINS AND NEEDLES, ARTIFICIAL FLOWERS. REGISTRATION OF THIS TRADE MARK SHALL GIVE NO RIGHT TO THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE word LACE. 5899 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 3692301 01/12/2017 Mr. RAJESHKUMAR JAMNADAS FULETRA “SHREE UMIYA NIVAS”, 5 – NEW PAPAIYA WADI, NEAR SAGAR HALL, GOKULDHAM MAIN ROAD, GONDAL ROAD, RAJKOT – 360 004 (GUJARAT) INDIA. Individual Address for service in India/Attorney address: TRADESAFE GANSHYAM HOUSE, NO.9, SHRINAGAR SOCIETY, OPP. SARDAR PATEL STADIUM, NEAR GOLDEN TRIANGLE, AHMEDABAD - 380 014 - GUJARAT Proposed to be Used AHMEDABAD LACE AND EMBROIDERY, RIBBONS AND BRAID; BUTTONS, HOOKS AND EYES, PINS AND NEEDLES; ARTIFICIAL FLOWERS; HAIR DECORATIONS; FALSE HAIR. 5900 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 3704300 16/12/2017 RAHUL BANSAL W-300, CHANDER SHEKHAR GALI, BABAR PUR, SHAHDARA, DELHI-110032 INDIVIDUAL Address for service in India/Attorney address: TYAGI CERTIFICATIONS 3/112, GROUND FLOOR, LALITA PARK, LAXMI NAGAR, DELHI-110092 Used Since :01/05/2003 DELHI SAREE FALLS 5901 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 26 PRIDE 3743090 02/02/2018 VINOD GARG N-119, SECTOR NO-1, BAWANA IND. -

Iran (Persia) and Aryans Part - 1

INDIA (BHARAT) - IRAN (PERSIA) AND ARYANS PART - 1 Dr. Gaurav A. Vyas This book contains the rich History of India (Bharat) and Iran (Persia) Empire. There was a time when India and Iran was one land. This book is written by collecting information from various sources available on the internet. ROOTSHUNT 15, Mangalyam Society, Near Ocean Park, Nehrunagar, Ahmedabad – 380 015, Gujarat, BHARAT. M : 0091 – 98792 58523 / Web : www.rootshunt.com / E-mail : [email protected] Contents at a glance : PART - 1 1. Who were Aryans ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. Prehistory of Aryans ..................................................................................................................... 2 3. Aryans - 1 ............................................................................................................................................ 10 4. Aryans - 2 …............................………………….......................................................................................... 23 5. History of the Ancient Aryans: Outlined in Zoroastrian scriptures …….............. 28 6. Pre-Zoroastrian Aryan Religions ........................................................................................... 33 7. Evolution of Aryan worship ....................................................................................................... 45 8. Aryan homeland and neighboring lands in Avesta …...................……………........…....... 53 9. Western