Changes in Numbers and Distribution of Wintering Long-Tailed Ducks Clangula Hyemalis in Swedish Waters During the Last Fifty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Foreign Submarine

Foreign submarine A serious political conflict between Sweden and the Soviet Union, in which a Lund physicist played an active role. Foreign submarine 426 427 Foreign submarine in Swedish archipelago On the evening of 28 October 1981 the front pages of the newspapers were filled with a surprising piece of news. A Soviet submarine on a secret mission had run aground on a rock in Blekinge archipelago. It was well inside a restricted military area and not far from Karlskrona naval base. Heightened state of alert Swedish military units from the navy and coastal rangers, among others, were assembled in the area over the following days. A large area was cordoned off. Helicopters and fighter aircraft patrolled the airspace and Swedish submarines were stationed underwater along the limit of territorial waters. The naval ship Thule was stationed as a barrier in the strait out towards open water. Foreign submarine 428 429 In all probability armed In an extra edition of the television news pro- gramme Aktuellt, a week after the grounding, Prime Minister Torbjörn Fälldin revealed that the submarine: ”… in all probability …” was armed with nuclear weapons. Political activity in Sweden and internationally was great. This was world news! Dagens Nyheter, 6 November 1981. The day after the Prime Minister’s revelation that there were nuclear weapons on board the submarine U137. On a secret mission In order to investigate whether the submarine was armed with nuclear weapons, measurements of the ionising radiation needed to be carried out. Reader Ragnar Hellborg from the Department of Physics in Lund was one of those who performed the measure- ments on behalf of the Swedish Defence Research Agency: It was around dinnertime on All Hallows’ Eve when the phone rang. -

BR List 2012B.Xls.Xlsx

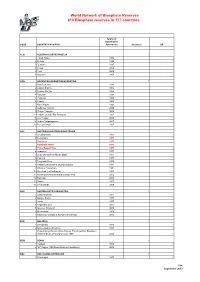

World Network of Biosphere Reserves 610 Biosphere reserves in 117 countries Approval Approbation CODE COUNTRY/PAYS/PAIS Aprobacion Countries BR ALG ALGERIA/ALGERIE/ARGELIA 1 1 Tassili N'Ajjer 1986 1 2 El Kala 1990 1 3 Djurdura 1997 1 4 Chréa 2002 1 5 Taza 2004 1 6 Gouraya 2004 1 ARG ARGENTINA/ARGENTINE/ARGENTINE 1 1 San Guillermo 1980 1 2 Laguna Blanca 1982 1 3 Costero Del Sur 1984 1 4 Ñacuñan 1986 1 5 Pozuelos 1990 1 6 Yaboty 1995 1 7 Mar Chiquito 1996 1 8 Delta des Paraná 2000 1 9 Riacho Teuquito 2000 1 10 Laguna Oca del Rio Paraguay 2001 1 11 Las Yungas 2002 1 12 Andino Norpatagonica 2007 1 13 Pereyra Iraola 2007 1 AUL AUSTRALIA/AUSTRALIE/AUSTRALIA 1 1 Croajingalong 1977 1 2 Kosciuszko 1977 1 Southwest 1977 Macquarie Island 1977 3 Prince Regent River 1977 1 4 Unnamed 1977 1 5 Uluru (Ayers Rock-Mount Olga) 1977 1 6 Yathong 1977 1 7 Fitzgerald River 1978 1 8 Hattah-Kulkyne NP & Murray-Kulkyne 1981 1 9 Wilson's Promontory 1981 1 10 Riverland (ex Bookmark) 1977 1 11 Mornington Peninsula and Western Port 2002 1 12 Barkindji 2005 1 13 Noosa 2007 1 14 Great Sandy 2009 1 AUS AUSTRIA/AUTRICHE/AUSTRIA 1 1 Gossenköllesse 1977 1 2 Gurgler Kamm 1977 1 3 Lobau 1977 1 4 Neusiedler See 1977 1 5 Grosses Walsertal 2000 1 6 Wienerwald 2005 1 7 Salzburger Lungau & Kärntner Nockberge 2012 1 BYE BELARUS 1 1 Berezinskiy 1978 1 2 Belovezhskaya Pushcha 1993 1 Pribuzhskoye Polesie (West Polesie Transboundary Biosphere 3 Reserve Belarus/Poland/Ukraine TBR) 2012 1 BEN BENIN 1 1 Pendjari 1986 1 2 "W" Region (TBR Benin/Burkina Faso/Niger) 2002 1 BOL BOLIVIA/BOLIVIE/BOLIVIA -

Planning for Tourism and Outdoor Recreation in the Blekinge Archipelago, Sweden

WP 2009:1 Zoning in a future coastal biosphere reserve - Planning for tourism and outdoor recreation in the Blekinge archipelago, Sweden Rosemarie Ankre WORKING PAPER www.etour.se Zoning in a future coastal biosphere reserve Planning for tourism and outdoor recreation in the Blekinge archipelago, Sweden Rosemarie Ankre TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE………………………………………………..…………….………………...…..…..5 1. BACKGROUND………………………………………………………………………………6 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….…6 1.2 Geographical and historical description of the Blekinge archipelago……………...……6 2. THE DATA COLLECTION IN THE BLEKINGE ARCHIPELAGO 2007……….……12 2.1 The collection of visitor data and the variety of methods ………………………….……12 2.2 The method of registration card data……………………………………………………..13 2.3 The applicability of registration cards in coastal areas……………………………….…17 2.4 The questionnaire survey ………………………………………………………….....……21 2.5 Non-response analysis …………………………………………………………………..…25 3. RESULTS OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY IN THE BLEKINGE ARCHIPELAGO 2007………………………………………………………………..…..…26 3.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………...……26 3.2 Basic information of the respondents………………………………………………..……26 3.3 Accessibility and means of transport…………………………………………………...…27 3.4 Conflicts………………………………………………………………………………..……28 3.5 Activities……………………………………………………………………………....…… 30 3.6 Experiences of existing and future developments of the area………………...…………32 3.7 Geographical dispersion…………………………………………………………...………34 3.8 Access to a second home…………………………………………………………..……….35 3.9 Noise -

Usage of Experience of Development of Territories with Similar Socio- Economic Characteristics Taken As a Whole As an Instrument of Kronshtadt Sustainable Development

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Kozyreva, Maria Conference Paper Usage of experience of development of territories with similar socio- economic characteristics taken as a whole as an instrument of Kronshtadt sustainable development 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe", 27th - 30th August 2003, Jyväskylä, Finland Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Kozyreva, Maria (2003) : Usage of experience of development of territories with similar socio-economic characteristics taken as a whole as an instrument of Kronshtadt sustainable development, 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe", 27th - 30th August 2003, Jyväskylä, Finland, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/115987 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Sustainable Development Strategy of the Baltic Sea Cycle Route Copenhagen - Rostock - Gdańsk (2030)

Sustainable development strategy of the Baltic Sea Cycle Route Copenhagen - Rostock - Gdańsk (2030) Gdańsk, November 2017 r. 1 Zawartość 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Target groups .................................................................................................................................. 6 3. Planned outputs of the document .................................................................................................. 7 4. Baltic Sea Cycle Route - general information .................................................................................. 7 4.1. Denmark .................................................................................................................................. 8 4.2. Germany: Land Schleswig-Holstein ....................................................................................... 10 4.3. Germany: Land Mecklemburg-Vorpommern ........................................................................ 11 4.4. Poland: Zachodniopomorskie Voivodeship ........................................................................... 12 4.5. Poland: Pomorskie Voivodeship ........................................................................................ 1413 4.6. Poland: Warmia and Mazury Voivodeship ............................................................................ 15 4.7. Russia Federation: Kaliningrad District ................................................................................. -

A Bell Tower on Swedish Locals by Christer Brunström, AIJP

Cinderella Time: A Bell Tower on Swedish Locals By Christer Brunström, AIJP In the 1920s and mid 1940s Sweden had a large num- ber of privately operated local posts that operated in com- petition with the Swedish Post Office. These local services delivered mail on a local basis at rates much lower than those charged by the state-run postal service. Many of these private posts issued stamps having very local designs. During my travels in Sweden I try to seek out the buildings and artworks depicted on the stamps in order to find out what they look like today. In the summer of 2014 my travels took me to the city of Karlskrona, the capital of the province of Bleking in the south-eastern corner of Swe- den. It was from the ports of this province that many thou- sands of Swedish emigrants left for a better life in North America in the late 1800s. Today Karlskrona is a city of some 35,000 people. It has been declared a World Heri- tage site by the UNESCO. The city was founded by King Karl XI in 1680. It is built on a number of islands in the Blekinge archipelago and it was the ideal spot to build a Swedish naval base to defend and expand Swedish domi- nation of the Baltic Sea area. The architect of the new city was Erik Dahlberg. He not only designed the city but also the fortresses and the shipyards. The naval shipyard was developed by Fredrik af Chapman. In the late 18th century, Karlskrona was Sweden’s third largest city after Stockholm and Riga (yes, Latvia was part of the Swedish Baltic empire at the time). -

Submarine Intrusions in Swedish Waters During the 1980S by Bengt Gustafsson

Parallel History Project on Cooperative Security (PHP) January 2011 E-Dossier, Submarine Intrusions in Swedish Waters During the 1980s www.php.isn.ethz.ch By Bengt Gustafsson Submarine Intrusions in Swedish Waters During the 1980s By Bengt Gustafsson The Truth is in the Eye of the Beholder Conspiracy theories, alternative explanations, and urban legends frequently play important roles in shaping public perceptions of high-profile events in history. Such alternative views are sometimes based on ideological preconceptions, the failure to appreciate the complexity of issues, or specific preconceptions about individuals, occupations, or institutions. In Sweden, the reception of what is known as ‘the submarine issue’ is a prominent example of such dynamics. The Swedish armed forces assert that from the middle of the 1970s until autumn 1992, foreign submarines repeatedly conducted intrusions far into Swedish territorial waters, including in the direction of the country’s naval bases. There was only one occasion on which the nation responsible for the incursion was successfully identified – when a Soviet Whiskey class submarine was discovered to have run aground in a bay just east of Karlskrona Naval Base in southern Sweden and was found on the morning of 28 October 1981. Journalists covered the event under headlines such as ‘Whiskey on the Rocks’. In Sweden, this event is known as the ‘U-137-incidenten’ *‘U-137 Incident’+ after the temporary designation given to submarine S-363 by the Soviet Union for the operation. In September of the previous year, the last Swedish destroyer in service, HMS Halland, had been deployed against a pair of submarines that were discovered in the outer Stockholm archipelago. -

More Maritime Safety for the Baltic Sea

More Maritime Safety for the Baltic Sea WWF Baltic Team 2003 Anita Mäkinen Jochen Lamp Åsa Andersson “WWF´s demand: More Maritime Safety for the Baltic Sea – Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) status with additional proctective measures needed Summary The scenario of a severe oil accident in the Baltic Sea is omnipresent. In case of a serious oiltanker accident all coasts of the Baltic Sea would be threatened, economic activities possibly spoiled for years and its precious nature even irreversibly damaged. The Baltic Sea is a unique and extremely sensitive ecosystem. Large number of islands, routes that are difficult to navigate, slow water exchange and long annual periods of icecover render this sea especially sensitive. At the same time the Baltic Sea has some of the most dense maritime traffic in the world. During the recent decades the traffic in the Baltic area has not only increased, but the nature of the traffic has also changed rapidly. One important change is the the increase of oil transportation due to new oil terminals in Russia. But not only the number of tankers has increased but also their size has grown. The risk of an oil accident in the Gulf of Finland will increase fourfold with the increase in oil transport in the Gulf of Finland from the 22 million tons annually in 1995 to 90 million tons in 2005. At the same time, the cruises between Helsinki and Tallinn have increased tremendously, and this route is crossing the main routes of vessels transporting hazardous substances. WWF and its Baltic partners see that the whole Baltic Sea needs the official status of a “Particularly Sensitive Sea Area” (PSSA) to tackle the environmental effects and threats associated with increasing maritime traffic, especially oil shipping, in the area. -

Biosphere Reserve Blekinge Archipelago Heleen Podsedkowska Coordinator February 28Th, 2012

Blekinge Archipelago Biosphere Reserve – a sea of opportunities! www.blekingearkipelag.se Blekinge Archipelago Biosphere Reserve Area (biosfärområde) Heleen Podsedkowska Coordinator 13 October 2016, Kärdla, Hiiumaa www.blekingearkipelag.se Agenda • Blekinge Archipelago BR, who we are and what we do • Examples on projects www.blekingearkipelag.se www.blekingearkipelag.se Biosphere reserves in Sweden • Kristianstads Vattenrike • Vänerskärgården med Kinnekulle • Älvlandskapet Nedre Dalälven • Blekinge Arkipelag • Östra Vätterbranterna Kandidatområden: • Vindelälven-Juhtatdahka • Voxnadalen www.blekingearkipelag.se www.blekingearkipelag.se NGO Blekinge Archipelago BR www.blekingearkipelag.se Some data • Area: 210 000 ha, 156 000 ha water, 54 000 ha terrestrial • 1 culture reserve, i.e. Ronneby Brunnspark • 37 nature reserves • 72 Natura 2000-områden (EU) • 85 000 inhabitants, about 4 000 living on islands of which some have land connection • Blekinge Institute of Technology – Master of Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability-programme www.blekingearkipelag.se Our vision Blekinge Archipelago - a sea of possibilities! Blekinge Archipelago represents a flourishing coastal area and archipelago where development occurs in harmony between entrepreneurship and ecology. Its foundation is local engagement and concern for the future of next generations. www.blekingearkipelag.se www.blekingearkipelag.se What makes Blekinge Archipelago so special? • Coastal fishing and small scale farming • Genuine living craft traditions, such as boat building -

Important Bird Areas and Potential Ramsar Sites in Europe

cover def. 25-09-2001 14:23 Pagina 1 BirdLife in Europe In Europe, the BirdLife International Partnership works in more than 40 countries. Important Bird Areas ALBANIA and potential Ramsar Sites ANDORRA AUSTRIA BELARUS in Europe BELGIUM BULGARIA CROATIA CZECH REPUBLIC DENMARK ESTONIA FAROE ISLANDS FINLAND FRANCE GERMANY GIBRALTAR GREECE HUNGARY ICELAND IRELAND ISRAEL ITALY LATVIA LIECHTENSTEIN LITHUANIA LUXEMBOURG MACEDONIA MALTA NETHERLANDS NORWAY POLAND PORTUGAL ROMANIA RUSSIA SLOVAKIA SLOVENIA SPAIN SWEDEN SWITZERLAND TURKEY UKRAINE UK The European IBA Programme is coordinated by the European Division of BirdLife International. For further information please contact: BirdLife International, Droevendaalsesteeg 3a, PO Box 127, 6700 AC Wageningen, The Netherlands Telephone: +31 317 47 88 31, Fax: +31 317 47 88 44, Email: [email protected], Internet: www.birdlife.org.uk This report has been produced with the support of: Printed on environmentally friendly paper What is BirdLife International? BirdLife International is a Partnership of non-governmental conservation organisations with a special focus on birds. The BirdLife Partnership works together on shared priorities, policies and programmes of conservation action, exchanging skills, achievements and information, and so growing in ability, authority and influence. Each Partner represents a unique geographic area or territory (most often a country). In addition to Partners, BirdLife has Representatives and a flexible system of Working Groups (including some bird Specialist Groups shared with Wetlands International and/or the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN)), each with specific roles and responsibilities. I What is the purpose of BirdLife International? – Mission Statement The BirdLife International Partnership strives to conserve birds, their habitats and global biodiversity, working with people towards sustainability in the use of natural resources. -

Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 347 Preliminary Report

Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 347 Preliminary Report Baltic Sea Basin Paleoenvironment Paleoenvironmental evolution of the Baltic Sea Basin through the last glacial cycle Platform operations 12 September–1 November 2013 Onshore Science Party 22 January–20 February 2014 Expedition 347 Scientists Published by Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Publisher’s notes Material in this publication may be copied without restraint for library, abstract service, educational, or personal research purposes; however, this source should be appropriately acknowledged. Core samples and the wider set of data from the science program covered in this report are under moratorium and accessible only to Science Party members until 20 February 2015. Published by International Ocean Discovery Program for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program and prepared by the European Consortium of Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD) Science Operator. Funding for the program is provided by the following agencies: National Science Foundation (NSF), United States Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD) Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), People’s Republic of China Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM) Australian Research Council (ARC) and GNS Science (New Zealand), Australian/New Zealand Con- sortium Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), India Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil Disclaimer Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the participating agencies, IODP, British Geological Survey, European Petrophysics Consortium, University of Bremen, or the authors’ institutions. Portions of this work may have been published in whole or in part in other International Ocean Discovery Program documents or publications.