Food Science Volume 9 Number 5, May 2015 ISSN 1996-0794

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

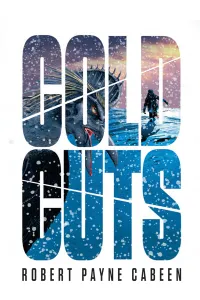

Cold Cuts 092317.Indd

COLD CUTS COLD CUTS B y R o b e r t P a y n e C a b e e n Omnium Gatherum Los Angeles Cold Cuts Copyright© 2017 Robert Payne Cabeen ISBN-13: 978-0997971767 ISBN-10: 0997971762 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author and publisher omniumgatherumedia.com. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is coincidental. First Edition For Cecile Bones in a basement, a snake in a tree, a rock on the moon, a ghost in the sea, a face in a crowd, a rip in a sheet, rust on a statue, a dog in the street. Everything is somewhere, so where are you now? So Sad Man A pernicious sadness squirmed into the man’s bones and wormed its way deep into his icy marrow. The only emotional shard that remained of his shattered psyche was sorrow. The sad man strained against his bonds, more out of habit than any real hope of breaking free. He unclenched his teeth, and gasped for breath. Nylon cord, cinched tight to his cot, restrained him, but the weight of his deranged captor crouch- ing on his chest was the primary cause of his worsening asphyxia. -

(Ofada) Rice in South-West Nigeria

HOUSEHOLDS’ CONSUMPTION AND QUALITY PERCEPTIONS OF LOCAL (OFADA) RICE IN SOUTH-WEST NIGERIA By: Ayodeji ’Seun Ogunleke Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements of the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Agricultural Economics School of Agricultural Earth and Environmental Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Supervisor: Prof. Lloyd J.S. Baiyegunhi March, 2020 DECLARATION 1: PLAGIARISM I, Ayodeji ’Seun OGUNLEKE, declare that: 1. The research reported in this thesis is my original research work; 2. This thesis has never been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university or institution of higher learning; 3. This thesis does not contain other authors’ data, pictures, tables, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from those authors. Where other written sources were quoted: a. Their words have been rephrased and duly referenced; b. General information attributed to them were duly referenced; and 4. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied from the Internet without having been specifically acknowledged and the source details mentioned in the reference section. Signed: Date: 06 /11/2019 Ayodeji ’Seun Ogunleke (Student) Signed: Date: 07 /11/2019 Prof. Lloyd J.S. Baiyegunhi (Supervisor) i DECLARATION 2: PUBLICATIONS The following publications form part of the research presented in this study. Publication 1 – Chapter three of this thesis. Ogunleke A.O. and Baiyegunhi L.J.S. (2019). Effect of Households’ Dietary Knowledge on Local (Ofada) Rice Consumption in South-West Nigeria. Journal of Ethnic Foods 6(24):1-11. Publication 2 – Chapter four of this thesis. Ayodeji Oluwaseun Ogunleke and Lloyd J.S. -

20-Delicacy-Ofada-Rice-Attributes

Draft Report Ltd. RC 378525 Communication and Marketing Research Group Limited Project Delicacy (Ofada Rice Attributes Evaluation Study) December, 2006 CMRG Ltd. PrOpCom 1 RC 378525 Report Layout Background Objectives & Action Standards Research Methodology Executive Summary • Key Findings From Qualitative • Key Findings From Quantitative Conclusions Marketing Considerations Appendix Detailed Report: Qualitative Detailed Report: Quantitative Housewives Professional Buyers Consumers List of Contacts CMRG Ltd. PrOpCom 2 RC 378525 Background Promoting Pro-Poor Opportunities in Commodity and Service Markets (PrOpCom) is an innovative project funded by the Department for International Development of the United Kingdom (DFID) to facilitate functionality and efficiency of Nigerian commodity and service markets in such a way as to assure these markets benefit the poor. PrOpCom’s goal is to improve livelihoods by facilitating growth and pro-poor outcomes in commodity and service markets and to contribute to the overarching (DFID/Nigeria) goal of poverty alleviation in support of NEEDS and the attainment of the Millennium Development Goals. PrOpCom will use a “Making Markets Work for the Poor” (M4P) approach to address the systemic reasons that prevent commodity and service markets from functioning effectively for the poor in Nigeria. In doing so, it will contribute to delivery of the vision for growth in the non-oil economy outlined in NEEDS. The project purpose is to support systemic change in markets on which the poor rely to produce pro-poor outcomes and opportunities such as: – Enhanced incomes; – Increased jobs; – Improved access to markets; – More options and choices; and – Reduced risks. CMRG Ltd. PrOpCom 3 RC 378525 Background Cont’d… PrOpCom would contribute to removing constraints to efficient market operations and linking market actors to work together and serve each other on a sustainable basis. -

Vf Ùf SEMI-ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY of RESEARCH IN

/Vf ùf U SEMI-ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RESEARCH IN POST-HARVEST TECHNOLOGY FOR. CEREAL GRAINS. AGO GRAIN LEGUMES IN AFRICAN COUNTRIES NORTH OF THF EQUATOR By W. D. Rolston For International Development Research Centre Ottawa Canada 1974 IDRC-doc-064 ARCHIV 016(6)633 R 6 NOTICE SEMI-ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY It is a policy of the IDPC to publish only bibliographies OF that can be taken as reference works. For developing-country users in particular, it is important not to spend time and RESEARCH IN POST-HARVEST TECHNOLOGY foreign exchange in trying to locate and obtain the docu- ment corresponding to an incorrect citation. To reduce FOR CEREAL GRAINS AND GRAIN LEGUMES the frustration of providing references to documents that are not available in developing-country libraries, we IN generally try to support our bibliooraphies with collections of the documents themselves so that we can provide photo- AFRICAN COUNTRIES NORTH OF THE EQUATOR copies on request. This bibliography has been compiled from a variety of unverified sources, including correspondence, personal collections, large data bases and libraries, and only a small proportion of the documents themselves have been located. It thus does not meet our own criteria for publication and wide distribution. Nevertheless, in order to gain the maximum benefit from the painstaking work of the author, we are making photocopies available By to IDRC's colleague institutions with the warning that we are unable to guarantee the accuracy of any citation or W.D. Rolston the availability of any document cited. We hope that the bibliography will be found to be useful. -

Chukwuemeka Et Al.Pdf

©2016 Scienceweb Publishing International Journal of Biotechnology and Food Science Vol. 4(1), pp. 7-14, January 2016 ISSN: 2384-7344 Research Paper Effects of processing methods on physicochemical, functional and sensory properties of Ofada rice *Anuonye JC • Daramola OF • Chinma CE • Banso O Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Niger State. *Corresponding Author‟s email: [email protected], [email protected] Accepted 12th December 2015 Abstract. Ofada rice samples were obtained from Ofada village in Ogun State, Nigeria. The samples were parboiled and milled using both the traditional Ofada processing (soaking for eight days) and the improved rice processing method (the hot water soaking method). A known rice variety “FARO 42” was parboiled and milled by the same methods for comparisons. The physicochemical composition, the pasting characteristics, and the acceptability of the samples were analyzed. The results showed that the protein content of Ofada rice processed by the two methods ranged from 8.26 to 9.92% with Ofada rice samples processed by the improved method having significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher protein (9.92%) and other proximate values than the samples from the prolonged soak method (8.26%). The milled rice samples showed that samples from prolonged soaking had lower milling returns (75.80%) compared to 79.35% for samples processed with the improved method. Prolonged soaking also led to significant (P ≤ 0.05) decreases in the pasting values of the Ofada samples. The sensory analysis showed that there were no significant (p ≤ 0.05) differences in the taste of Ofada and FARO 42 samples processed by the prolonged soaking method. -

Classic Nigerian Food Recipes

CLASSIC NIGERIAN FOOD RECIPES This ebook is an Intellectual Property of Michael Toye Faleti © All rights reserved The content of this ebook is not warranted for correctness, and is used by the reader at his/her own will. No other warranty is given for using the content of this ebook. 1 INTRODUCTION This ebook is written as a guide to learning how to cook Nigerian foods. You will find fifteen main recipes of some of the most popular dishes enjoyed all across southern Nigeria. So why make an ebook about Nigerian food recipes? Firstly, I love Nigerian foods. I think Nigerian cuisine has penerated a lot of cultures across the world and many people are becoming more curious of African cuisine in general. However, this ebook is for women and maybe men who are Nigerians or have been influenced by the culture through marriage, family or friendship to broaden their knowledge about Nigerian cuisine and develop their confidence in the kitchen. And most importantly for the young women starting out wanting to become better skilled at the Nigerian culinary arts. If you are Yoruba and have always wanted to learn how to cook Ibo food then there are plenty of Ibo food recipes here to get you started. Or maybe you learned to cook Nigerian foods in countries like the U.S, Great Britain, South Africa or elsewhere and want to improve on the recipes you know or learn some new ones. This ebook will take your cooking to the next level by extending the range of Nigerian foods you can cook and teach you how to combine native ingredients to get the most authentic flavour and taste. -

A Historical Appraisal of Local Rice Production and Its Impact on The

African Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development ISSN: 2689-5080 Volume 3, Issue 1, 2020 (pp. 33-47) www.abjournals.org A HISTORICAL APPRAISAL OF LOCAL RICE PRODUCTION AND ITS IMPACT ON THE AGRO-ECONOMIC SECTOR OF EKITI STATE 1945-2015 Ajayi Adeyinka Theresa (Ph.D)1, Oyewale Peter Oluwaseun (Ph.D)2 and Ogunleye Opeyemi Racheal3 1Department of History and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Ekiti State University, Ado – Ekiti, Nigeria. Phone NO: +2348035071804 2Department of History and International Studies, Faculty of Arts, Ekiti State University, Ado – Ekiti, Nigeria. Phone No: +2348034354343 3Federal University, Oye Ekiti, Ekiti State ABSTRACT: The study examines the historical development of local rice production and its economic important to the people of Ekiti State between the period of 1945-2015. Local rice was introduced in Ekiti land during the colonial years by the Christian missionaries but started gaining ground in the post independent years. Ekiti people are well-known as the major producers of local rice. Its production in Ekiti started long before 1945 but the year 1945 has been chosen as a remarkable date due to the activities of a well-known Igbemo farmer who specialized in the production of local rice and yam, where local rice industry is said to have started in Ekiti state. The introduction and adoption of local rice into the agricultural sector of Ekiti land marked a significant epoch in the agro-economic sector of Ekiti people. On this note, this paper aim at making an assessment of the production of local rice and its overall implication on the economic growth and development of Ekiti people. -

Nigerian Social Worker Killed in Assisted Living Home In

BUY • SELL • LEASE • INVEST Higher Standards Agents... Higher Results! Buy • Sell • Lease THIS SPACE IS AVAILABLE CALL FOR FREE HOME EVALUATION Sunday (Sunny) Adodo Sales Representative Cell: 647-200-7359 FOR YOUR BRAND. Nana Osei-WirekoSales Representative HomeLife Woodbine Realty Inc., Brokerage Each Office Independently Owned & Operated 416.318.3506 Cell: 416-917-4298 680 Rexdale Blvd., Unit 202, Toronto ON M9W 0B5 www.NowHomesRealty.com Off: 416-741-4443 [email protected] [email protected] HomeLife/Miracle Realty Ltd., Email: [email protected] Each Office Independently Owned & Operated Brokerage Off: 905-455-5100 Fax: 416-679-0443 www.sundayadodo.com TO INFORM • EDUCATE • EMPOWER • ENTERTAIN THE NCNC CANADIAN NEWSPAPER Vol 14 | Issue 10 | OCTOBERNIGERI 2019 | “THE THIRD EYE OF THE COMMUNITY” | Tel: 416-318-3506 | [email protected] | Awww.nigeriancanadiannews.caN | CDN$1, US$1, N200 NIGERIAN SOCIAL WORKER KILLED IN RICHARD ODELEYE L A W F I R M ASSISTED LIVING HOME IN CALGARY (RICH LAW) By NCNC staff youth and families. While talking about The police have re- Deborah Onwu’s pain- vealed that a youth so- ful death, Wood’s Homes • Business Law cial worker working with spokeswoman Sylvia • Mining Law Wood’s Homes was fatally MacIver said: “Everyone stabbed recently while she at Wood’s Homes is deep- Area of Prac�ce • Nigerian Law was on duty taking care of ly impacted by this recent IMMIGRATION & REFUGEE • Immigration & Refugee Law a man. tragedy. Our thoughts and CIVIL LITIGATION. FAMILY LAW • Family Law and Adoption Deborah Onwu, aged prayers are with all in- CRIMINAL LITIGATION • Real Estate 47, who lived in Calgary, volved including the vic- 1110 Finch Avenue West, Tel: was discovered by police as tim’s family and our many Suite 815, Toronto 416-733-8585 Ontario M3J 3J4 Fax: 416-733-0009 the victim. -

Edited by Robert Jobson

Edited by Robert Jobson QUEEN & COMMONWEALTH QUEEN & COMMONWEALTH The Queen and Nelson Mandela, President of South Africa, driving through London in a carriage on 9 July 1996. QUEEN & COMMONWEALTH © Henley Media Group, 2016 Text written by Robert Jobson, unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright owners. The contents of this book are believed correct at the time of printing. Nevertheless the publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused. Printed in Malta by Gutenberg Press Ltd. A catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-9928020-6-6 Published by Henley Media Group Two America Square, London, EC3N 2LU, UK Tel: +44 (0)207 871 0123 Email: [email protected] Website: henleymediagroup.com Chairman: Nigel Barklem Publisher: Deep Marwa Managing Publisher: Alex Halpin Managing Editor: Jane Nethersole Subeditor: John Saunders Commercial Manager: Michael Malcolm Designer: Daniel Harland Brown With special thanks to Elizabeth van der Valk and Hilary Greengrass at the Royal Commonwealth Society for their continuous support and wisdom. 4 QUEEN & COMMONWEALTH Edited by Rob Jobson Published for the Royal Commonwealth Society by Henley Media Group 5 QUEEN & COMMONWEALTH Queen Elizabeth -

Sanni Amike CPA ENCOMIUMS AS NIGERIAN, CHIKA ORIUWA

Higher Standards Agents... Higher Results! Buy • Sell • Lease THIS SPACE IS AVAILABLE Sunday (Sunny) Adodo Sales Representative PUBLISHING FOR YOUR BRAND. Cell: 647-200-7359 HomeLife Woodbine Realty Inc., Brokerage Each Office Independently Owned & Operated SINCE 2005 416.318.3506 680 Rexdale Blvd., Unit 202, Toronto ON M9W 0B5 Off: 416-741-4443 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: 416-679-0443 www.sundayadodo.com TO INFORM • EDUCATE • EMPOWER • ENTERTAIN THE NCNC CANADIAN NEWSPAPER CANADA Vol 15 | Issue 5 | MAY 28 - JUNENIGERI 28, 2020 | “THE THIRD EYE OF THE COMMUNITY” | Tel: 416-318-3506 | [email protected] | www.nigeriancanadiannews.caAN | CDN$1, US$1, N200 ENCOMIUMS AS NIGERIAN, CHIKA RICHARD ODELEYE Sanni Amike CPA L A W F I R M Professional Corporation ORIUWA MAKES HISTORY AT UNIVERSITY (RICH LAW) Accounting/Tax/Mgt. Services OF TORONTO for the right reason. Chika Oriuwa has proven that co- lour, race or background is no excuse if one is deter- SERVICES: mined to achieve greatness. Area of Prac�ce • Personal Tax & Corporate Tax Indeed, Chika has IMMIGRATION & REFUGEE • Bookkeeping & Payroll earned herself a name in • Tax Planning • CRA Audit CIVIL LITIGATION. FAMILY LAW history haven graduated as CRIMINAL LITIGATION • Legal Practice Accounting a valedictorian in the Uni- • Law Society Audit 1110 Finch Avenue West, versity of Toronto’s medical Suite 815, Toronto • Company Registration/Restructuring class of 259 that had her as Ontario M3J 3J4 info@richlawfirm.ca the only black. www .richlawfirm.ca CONTACT: Oriuwa is the first Black Tel. (416) 603-9195 416-803-2632 woman to be honoured with Fax: (416) 603-9190 [email protected] the accolade at the school www.sanniamikecpa.ca and the first woman in 14 nizing the value of the work 1280 Finch Avenue West years. -

West Africa's Largest Food and Beverage Trade Exhibition!

September 1st–3rd 2021 | Landmark Centre, Victoria Island, Lagos SHOW GUIDE 2021 WEST AFRICA’S LARGEST FOOD AND BEVERAGE TRADE EXHIBITION! Gold Sponsors: Silver Sponsor: Professional Partners: CASA DE CAMPO Show Partners: Media Partners: FABWestAfrica fabwestafrica www.fab-westafrica.com [email protected] +442476158099 SHOW GUIDE 2021 GUIDE INDEX WELCOME LETTER 6 EXHIBITION FLOORPLAN & EXHIBITOR LIST 7 EXHIBITOR PROFILES 11 ADMISSION: Canvassing for orders by unauthorised persons is prohibited and will necessitate Admission to the exhibition is free of charge expulsion. to everyone pre-registered. No handbills or placards may be affixed Registering on-site is possible, but comes at to any part of the building or site area. a cost of 1000 Naira per ticket. No material printed or otherwise, may be Wednesday, 1st September distributed in any part of the site without 10:00am to 05:00pm the express permission of the Organisers. Thursday, 2nd September No photography or filming is permitted 10:00am to 05:00pm anywhere in the Exhibition hall without the express written permission from the Friday, 3rd September Organisers. 10:00am to 05:00pm DISCLAIMER: Children under the age of 16 will not be admitted. Details published in this guide are based on information supplied by exhibitors or by the CATERING AND REFRESHMENTS: organisers of joint ventures. A cash-basis refreshment facility (Café) is The Organiser, BtoB Events can accept no available within the exhibition hall. responsibility for inaccurate or misleading FIRST AID: information, although every effort has been made to ensure that information is accurate Please visit the organiser’s office for all first at the time of printing. -

26-Definition-Of-Ofada-Rice-Qualities

PrOpCom Making Nigerian Agricultural Markets Work for the Poor Monograph Series # 26 DEFINITION OF OFADA RICE QUALITIES THROUGH VARIETAL IDENTIFICATION AND TESTING By National Cereals Research Institute (NCRI) Badeggi P.M.B. 8, Bida, Niger State, Nigeria (J. C. Anounye, N. Danbaba, A.S. Gana and M. E. Abo) And Africa Rice Centre, (WARDA), c/o International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. PMB 5320, Oyo Road, Ibadan, Nigeria (G. Gregorio, O.A. Oladimeji, B. Athanson, O. Ajayi, and F.E. Nwilene) August, 2007 Funding for this programme is provided by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) 40 Mississippi Street, Maitama, Abuja, Nigeria • Tel: +(234) 9 413 8291/2 • Fax: +(234) 9 413 829 1 Disclaimer The PrOpCom Monograph Series seeks to provide a broader dissemination of the information and views collected through the efforts of the various service providers and consultants undertaking work in support of the PrOpCom programme. We believe this information will be useful in informing the policy dialogue in Nigeria and for improving the planning and execution of agricultural and agribusiness activities within the country. The documents in this series represent the final deliverables as presented by the engaged service providers or consultants in responds to terms of reference of contracts let by PrOpCom in execution of its programme. They have not been further edited or editorially polished. Consequently, there is wide variation in the editorial quality of these documents. Nevertheless, the information contained in these document is deems useful for policy and planning purposes. The views and opinions expressed in these documents are solely those of the authors of the document and do not necessarily represent the views of PrOpCom, SAII Associates, Chemonics International or PrOpCom’s funding agent, the Government of the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) Information from these documents can be freely used and quoted on condition that it is properly sourced to the concerned document.